At NFX we study network effects in the wild so we can help founders build them better. Sometimes it takes us a while to notice the pattern, but we now have another one.

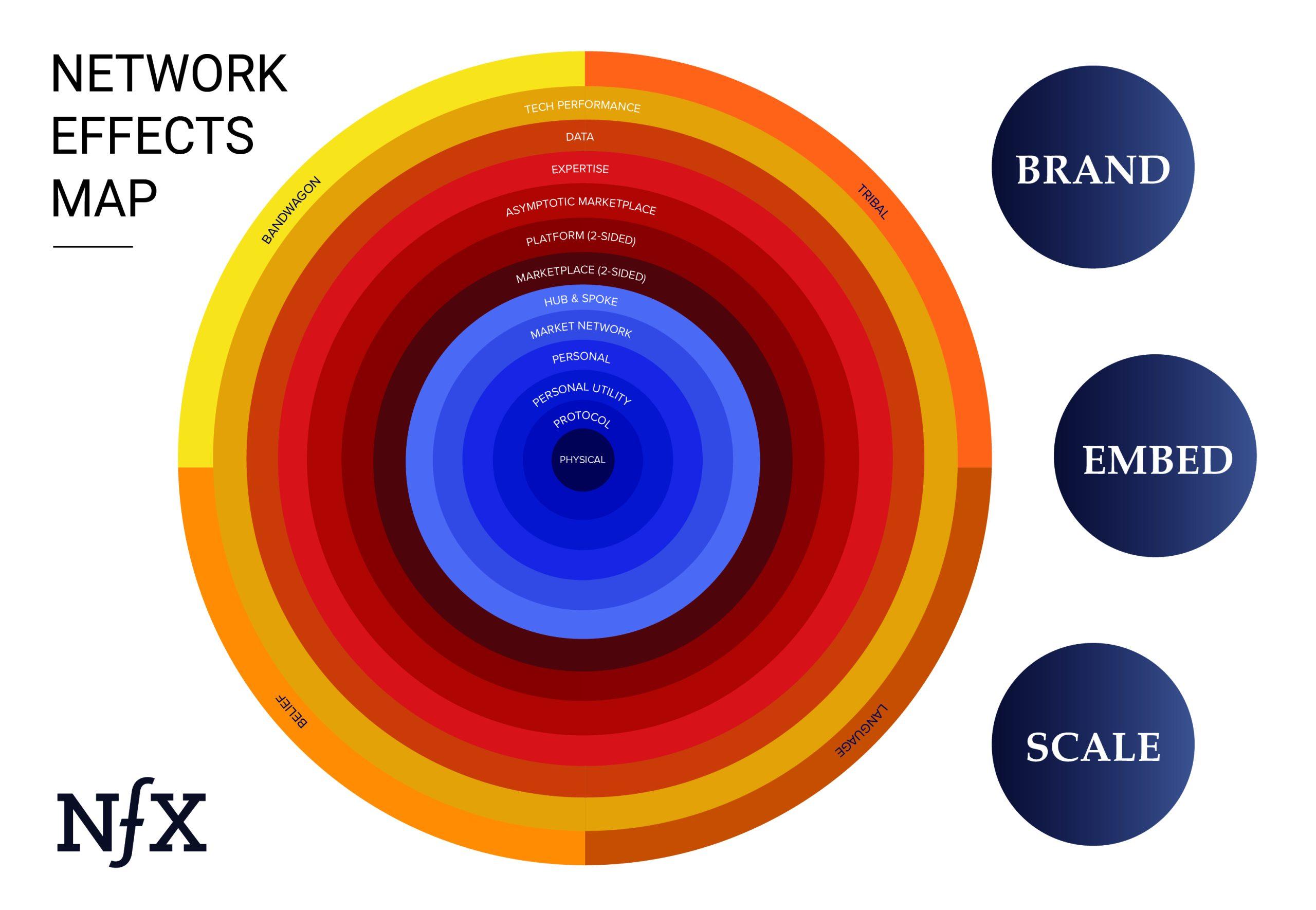

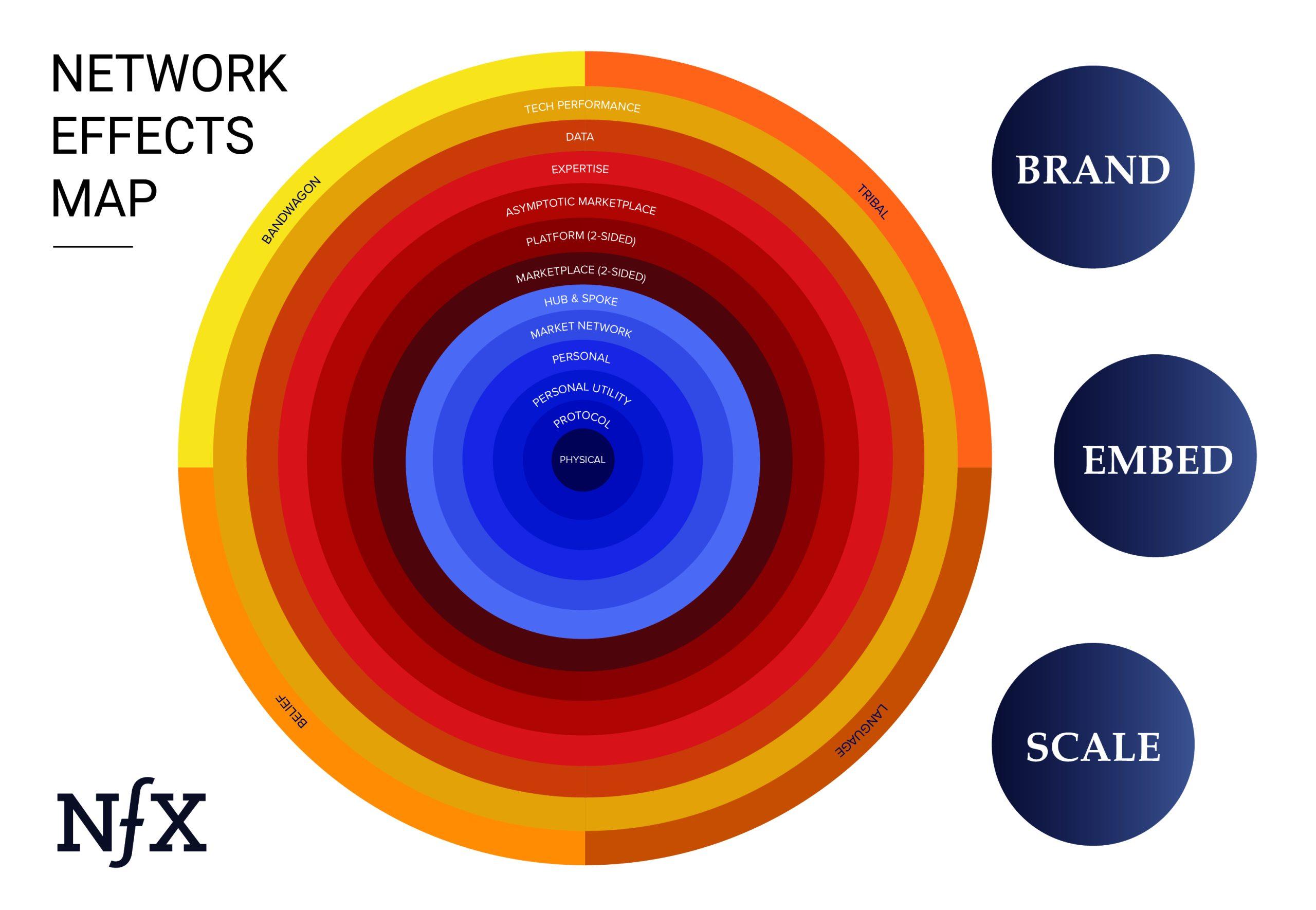

Meet the 16th Network Effect on our list: The Hub-and-Spoke Network Effect.

It’s the network effect that drove TikTok’s ascendance in 2016, Medium’s initial traction in 2013 until they blew it, and now that we can see the pattern, LiveJournal’s growth in 2000, and CraigsList’s growth in 1995.

This is a new addition to our Network Effects Map. It sits near the core in blue, among the other Direct network effects.

What we like about Hub-and-Spoke is that it’s particularly helpful to your startup right at the beginning of your journey.

It’s straightforward to implement and mixes well with other network effects in a pattern we call “reinforcement,” putting the startup on a solid path to creating long-term, durable defensibility.

Defining the Hub-and-Spoke Network Effect

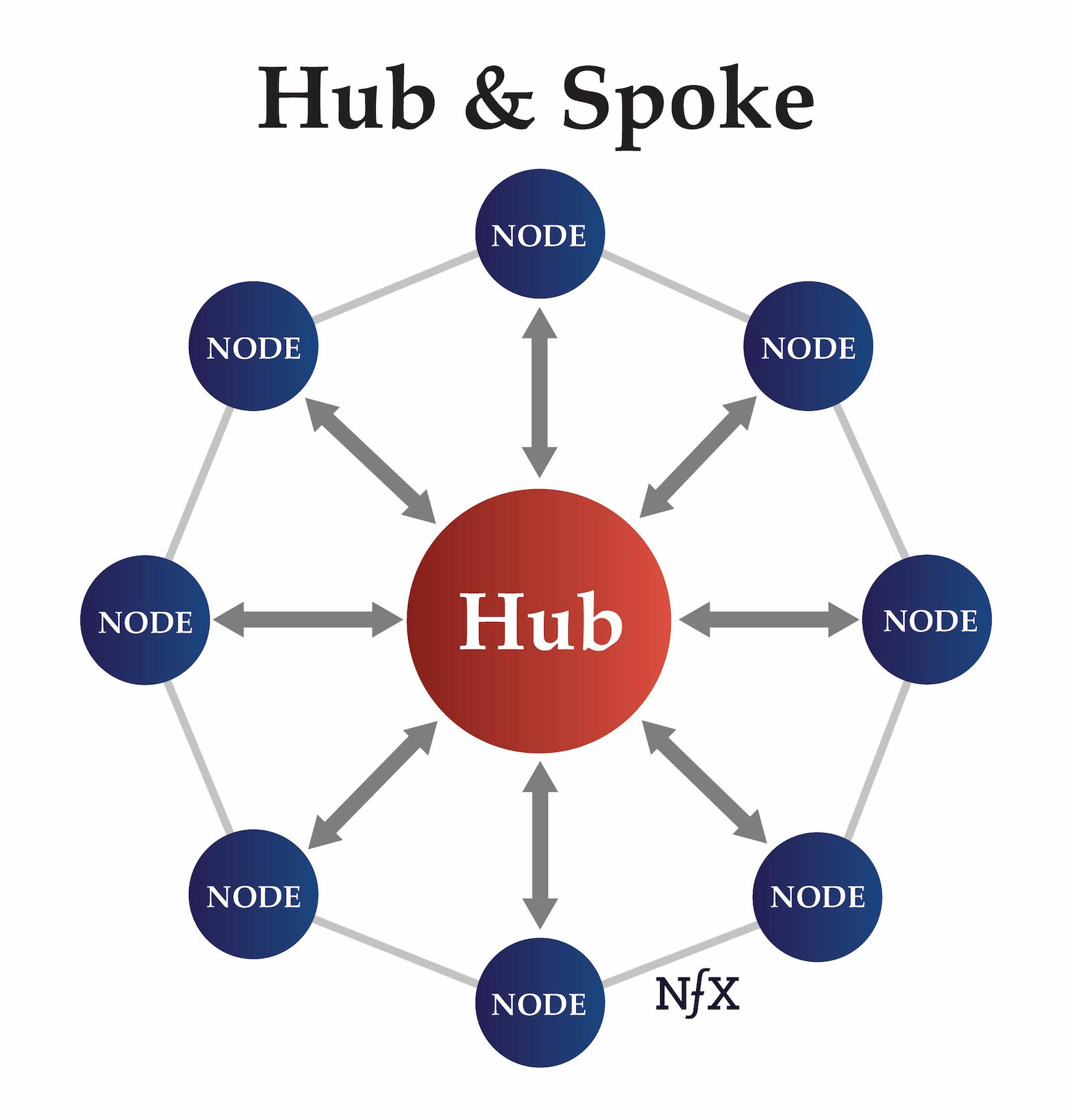

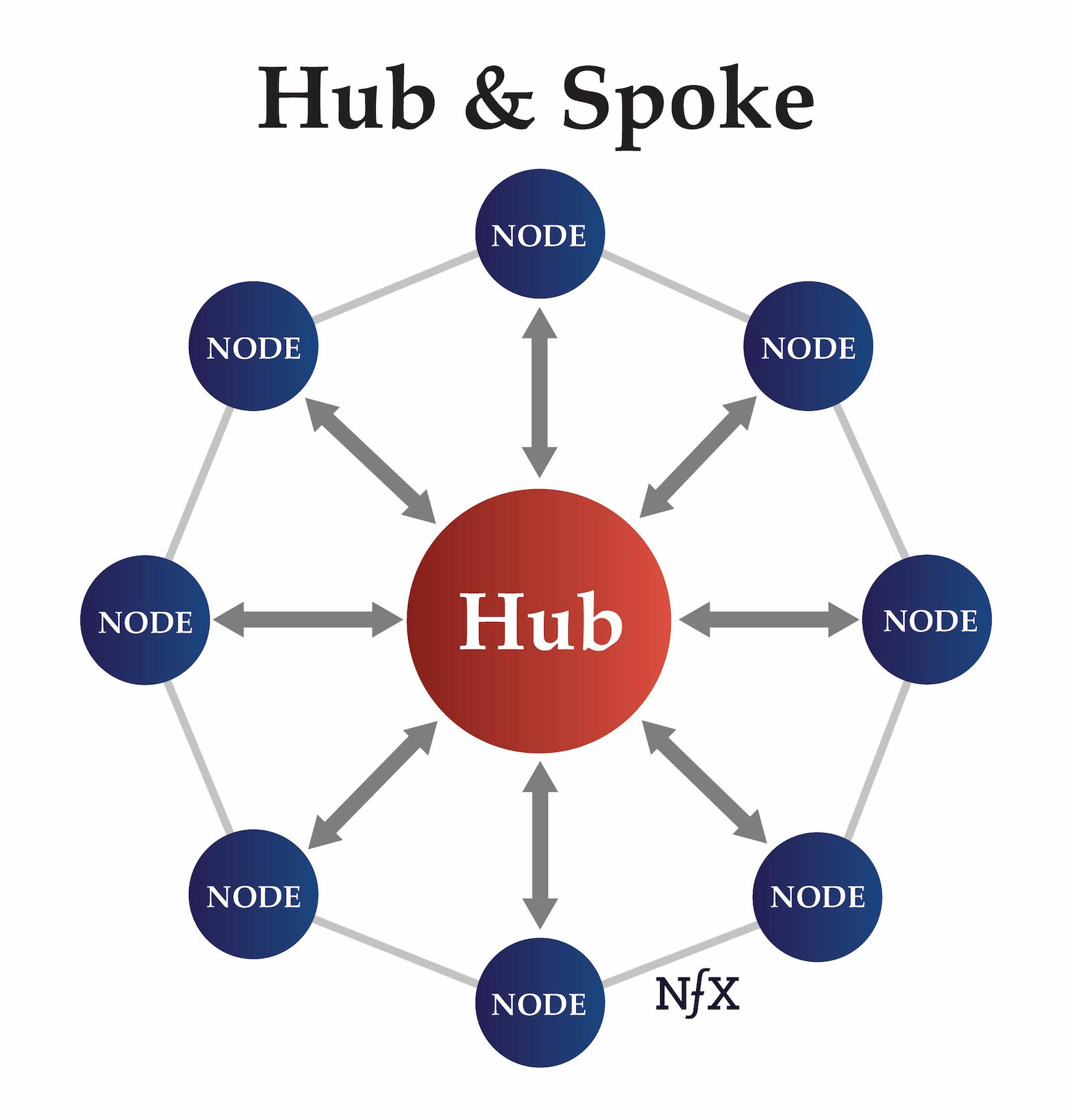

A Hub-and-Spoke network effect occurs when equal nodes submit content or goods to a central Hub. Then the Hub “pushes” a chosen few pieces out to all – or nearly all – of the nodes.

That elevation of the pushed content drives tremendous attention and value to those few lucky nodes, asymmetrically benefiting them relative to others in the network. In other words, it directs a power law within the system.

To a node, that process of selection feels like a lottery, and the benefits of selection are sudden and extreme compared to other direct networks like FB, Twitter, Snap. Because of that potential positive impact, nodes are incentivized to work hard to produce something of extreme quality hoping to be noticed, thereby adding a lot of value to the network in a short amount of time.

To the Hub, that selection is an algorithmic internal process.

As shown below, the network structure looks like a hub and spoke, thus the name. But unlike an old hub-and spoke-network like a TV or radio broadcasting network, which grows in value only by Sarnoff’s Law, this network grows with the power of Metcalf’s Law because it 1) harnesses the many nodes to create the content/products rather than take that burden itself, and 2) allows the nodes to connect with each other like a typical social network, driving more interactions and value.

TikTok

The media is breathless about TikTok, and even Zuckerberg is worried. How did they do it? With the Hub-and Spoke network effect.

People post their material to the Tiktok “hub.” And while that content is certainly visible to followers and anyone searching for it like it would be on Twitter or YouTube or Facebook, what the person is really on Tiktok for is to win TikTok’s unknowable algorithm and get pushed to millions of feeds.

When they are, then they gain dramatic numbers of likes, followers, and increased status. They can amplify attention far beyond the scope of their social networks in a week or two. On TikTok, you don’t need to already have 100,000 followers or be a celebrity to get famous.

The effect of this can’t be overemphasized. It’s possible that a future President of the United States will have started as a TikTok star. Don’t laugh. The last President was effectively a Twitter star.

But none of that happens if there aren’t many nodes using TikTok in the first place. No matter how powerful the Hub is. So to complete the TikTok story, I should mention what few know, that TikTok grew by spending billions of dollars over 3 years to drive user downloads, sometimes spending as much as $40 per download. For a business that was making $1-$5 per user in revenue per year, that was a risky, and *very smart* bet on driving a Hub-and-Spoke network effect. Now Tiktok is making about $65/user/yr in ad revenue. (Side note: we saw Didi, China’s ride hailing company, do something similar by giving rides away for free for years, spending $2B per year, to build its two-sided network effect between drivers and riders, and drive Uber out of China. Long term thinking, big spend, winner take most network effects. Fun to watch, hard to compete against.)

Medium

When it first started, Medium operated similarly, but the mechanism of pushing out content wasn’t to a feed in an app like TikTok – it was email.

When you joined Medium as a writer, you became an equal node in the network. You published on a sleek, refined platform, hoping that your friends would engage with your posts, and vaguely trusting that some proximity effect to other posts would get you more views, status, impact, whatever. Medium could have stopped there, but they leveled up to a Hub-and-Spoke network effect. Once a day, Medium pushed out an email to all its users with the best recent publications on-site.

Simple. But suddenly, it wasn’t just your friends seeing your writing on Medium. Thanks to Medium’s curation process, you could be pushed to the entire network. You might get 100,000 visitors on your post in a day if you won that lottery – and all the value that comes with that traffic. Having the chance to have 100,000 people see your blog post wasn’t something you could get anywhere else, thus the Medium network provided more value to all its users than they could get posting elsewhere. For a couple years there, everyone had to seriously consider moving all their blog posts to Medium to get the chance to have the traffic explosion from that push email.

Why Medium didn’t reach its full potential even after achieving a Hub-and-Spoke network effect would be a post for another time.

Seeing Hub-and-Spoke Models All Around You

Now that you know its architecture, you’ll begin to notice this Hub-and-Spoke network effect in many places.

Upon reflection, one of the first online businesses I can think of to employ a Hub-and-Spoke network effect was Craigslist in 1995. (NFX podcast with Craig, here.) In this case, people in San Francisco would send their classified postings for jobs or apartments to their friend Craig Newmark. He was the Hub. He would send out an email to everyone who posted or signed up to his email list. Although his algorithm happened to be “send everything to everyone,” be clear that that is an algorithm within the realm of all possible algorithms. It’s just an edge case: “zero curation.” Eventually that algorithm became too polluted as the network grew, so he adapted it to a website where you could sign up for email reminders for specific interests.

Another one that comes to mind is LiveJournal in 2000. Not many people today know about this company, as it was very early in the social media revolution, but it pioneered a lot of things, including a push email to a community of bloggers which in my mind was a Hub-and-Spoke network effect. Brad Fitzpatrick deserves a lot of credit, and Tumblr and Medium owe him a debt, as he led the way for their businesses.

There are offline examples of hub-and-spoke network effects as well.

Academic publishing, for instance. Scientists (nodes) will submit their life’s work to high-status journals (Hubs). If you’re selected and get pushed out to everyone reading that publication, you reap tremendous rewards: increased status, and, probably career advancement. Despite many people upset with these journals, they persist, and now you know why: Hub-and-Spoke network effect.

Another offline example is State-run sweepstakes. When you enter a sweepstakes, you – an equal node – send money (not content or products) to a central Hub with the hope of being randomly selected to win a prize. This is another extreme edge case algorithm which is “send one node everything.” The mere chance – as remote as it is – is so compelling that these sweepstakes can become unicorns in their own right. The 2016 Powerball pot amounted to $1.6 billion. And that wasn’t a fluke. The Mega Millions pot has surpassed one billion twice: in 2018 and 2021. These are so powerfully motivating that the government has made them illegal for anyone but them to run.

Maybe the Hub-and-Spoke network effect works because it meshes well with human nature – we are evolutionarily programmed to seek rewards, even if it means rolling the dice. Or perhaps, it plays into our intuition that we are exceptional and destined to beat the odds.

Simple to Start, but NOT a “Set and Forget” Network Effect

But here’s the thing. The Hub-and-Spoke network effect requires a lot of management. More than most people realize, particularly because it’s simple to start sending a daily email. It’s critical to design and continuously manage your Hub to create networks that avoid pollution, don’t asymptote, and evolve to match your user’s psychology as your network grows through many seasons. It’s not set and forget.

The Lottery: The Node Perspective

In the Hub-and-Spoke model, value primarily flows from the central Hub out to the nodes.

That, in some ways, makes the Hub-and-Spoke Network Effect a single-player game. As a node you’re there to play the Hub’s lottery. But this is a network effect because the nodes, though not always directly connected as in a marketplace or true social network, do still have something to offer one another.

Each new node sweetens the deal. Increases the size of the pot. Your action potential grows as the number of nodes in the network grows. And those that follow you, do increase the value of playing while you wait for the big win.

People sign up to play this Hub-and-Spoke game for a long list reasons:

- Attention/Fame

- Status

- Cash

- Sales

- Early access

- Premier software features

- Membership to a clique of other nodes

- Real world perks, like dinner or tickets to a concert

- Equity shares

- Discounted fees

- Some voting or decision-making ability

- … many more

But the important X factor that distinguishes the Hub-and-Spoke network effect is the perceived path to obtaining those rewards.

By inserting the central Hub into the middle of the network, you turn a hope into a lottery ticket in the node’s mind. Even a lottery has one central guarantee: winning is a certainty for at least one person. If we select you, the Hub promises, you can be that #1 and reap the power law’s rewards.

Designing Your Hub-and-Spoke

As a founder, designing one of these Hub-and-Spoke networks could be very impactful for you.

You have six main decisions.

- What are you collecting at the Hub? Videos, blog posts, new products for sale, classified listings, etc. We’ve already seen many examples.

- What is your algorithm for selecting what will be sent out from the Hub? What is the method for deciding? Who is involved? What metrics are involved?

- How transparent do you want the algorithm to be?

- How frequently do you push? Hourly? Daily? Monthly? Quarterly? (e.g. Medium pushed 1x daily)

- What channel do you push out through? An app on a mobile phone? Email? SMS? WhatsApp?

- Who do you send to? Everyone? Just people who have signed up for this type? Just people who have engaged with this type before?

Designing the Algorithm

Let’s focus on #2 and #3 above because they are the core of your business and the core of your startup’s narrative.

This algorithm is your mechanism for directing the power law within this network. These algorithms are the social contract you have with your nodes, and can be very different from one another.

For example, scientific journals use human-centric and months-long “peer review” as their algorithm, while TikTok has a real time algorithm that optimizes content for certain users based on previous behavior.

How do you design that algorithm? First, decide what inputs matter and feel natural to the network you’re building. Be intentional about this. Some you might consider include:

- Views

- Transactions

- Upvotes

- Downvotes

- Dwell time

- Likes

- Human-curation (Editor’s picks)

- Or, decide to use no data at all (random sweepstakes, and be open that it’s random).

How transparent do you want this process to be to your users? All algorithmic selection processes exist on a spectrum of transparency.

On one end, you could be completely opaque. In a true lottery, for example, it’s obvious that this is a random process. In fact, that’s part of the drama and appeal: there’s nothing you can do to game the system, it’s pure chance. And everyone knows it.

On the other hand, you could have a black box. TikTok is on this end of the spectrum. Users have a sense of what the algorithm does or doesn’t like, but it’s notoriously unknowable. In fact, if someone has done a really good job of building a deep learning algorithm, they wouldn’t expect to know why it makes the decisions it does, and TikTok falling into that category.

Perhaps for your startup, there is a sweet spot on this spectrum. One could be: “Be opaque enough to create the illusion of hackability.”

Perhaps you want as many people as possible trying to divine why certain things are chosen and why certain things are not. You want them to obsess over cracking your code, or build an industry around helping others crack it. We’ve seen this happen in network effect businesses that employ algorithmic features – for instance, SEO specialists exist because it’s a full time job to play this game with Google. If Google had a “push,” we would consider it a classic Hub-and-Spoke. But it’s not, as we describe further below.

Watch out for these 2 traps

To avoid pollution of your Hub-and-Spoke network, you’re going to need to dial up and dial down your algorithm’s inputs to ensure that you’re always pushing the right content, at the right time, at the right frequency, in the right channels, to the right people.

This process will differ depending on your network’s age and internal dynamics. However, you can go very wrong and kill this network effect over time. There are two traps to watch out for.

1. Beware of pushing things that may alienate your audience.

People care about communities that are built around power laws. When you start to change the way the power law is directed, your community will notice and react. Digg collapsed when major changes to the curation process sparked fights. Reddit, which I would consider Digg 1.2, has nearly collapsed into hysteria several times as moderation policies, Reddit’s algorithm for community-building, are called into question.

This can happen in communities that aren’t built around content as well. Imagine if a network like TopHatter, centered around auctions that start at $7 prices, became a place to auction off $65,000 cars. From your perspective as a Hub, it might be interesting to sell high-value items. But to the user, that could feel alienating. This isn’t a place for the original users anymore.

2. Look for signs of premature segmentation of your network.

It’s tempting, as you grow, to try to create more Hub systems within your network. You figure that creating more winners = winning. And in fact, your users will probably start demanding it. But if you do this too soon, you undercut the value of all the Hubs.

This is perhaps where Medium went wrong. Medium attempted to create curated email lists for each user. This torpedoed the lottery, not to mention the sense of community that lottery fostered. It meant that your best posts might be seen by 1,000 people, instead of 100,000.

Resist the temptation to make everyone a winner of an insignificant prize. That just weakens the strong power law you’ve tried to build.

This isn’t to say that you shouldn’t try to create sub-communities or more Hubs over time. But you should be careful about when you decide to evolve your network. You will know it is too soon if the prize is no longer valuable to those who win the Hub’s lottery.

Remember that your algorithm is actually a social contract with your users. How you tell that story, and how that story evolves over time is critical to maintaining a healthy network effect.

What is not a Hub-and-Spoke network effect business

At this point, the Hub-and-Spoke network effect may start to remind you of other businesses that center around curation, or the elevation of certain content, goods or services. What about Google? Is Google a Hub-and-Spoke network effect business?

It’s close, but not quite. And it’s important to understand why.

It seems like Google would be a natural fit. Websites (nodes) submit themselves to Google for indexing. Google employs an algorithm to comb through those nodes and rewards some with high search rankings. Google has the lottery: the algorithm. But it’s missing one feature: the push. At the end of the day, you still need to enter a search term into Google. You have to seek out the goods the Hub is curating, rather than the Hub pushing that to you.

That said, Google is close to a Hub-and-Spoke, and is perhaps benefitting from some bits and pieces of this network effect. But to fit squarely into this mode, the push is necessary.

The focus on the push is important, because it reveals where, and how you can incorporate this network effect into your business if you haven’t already.

How to use this Network Effect

You can design a Hub-and-Spoke network effect business from the ground up. But as we say with all network effects, it’s best to use them in combination.

Existing network businesses can graft on a Hub-and-Spoke network effect. Take Apple Podcasts for example. Apple Podcasts has nodes: tons of users who create and listen to podcasts each day. It has a Hub: it’s distribution platform, and, perhaps, more specifically, Apple’s genre-specific podcast charts.

Podcasts compete for placement on these charts, which is the key to growing an audience, and getting noticed. Apple does curate certain shows, but it’s all passive. And, it’s not networked. And there is no narrative around the algorithm or the value a creator might win.

What if, each time you got into the driver’s seat, Apple pushed the top-rated podcasts among your friends to your phone? What if the top shows were curated, organized, and pushed to users looking for recommendations, the way TikTok’s For You page curates videos?

Charts are passive, but pushes are active. They allow for discovery to happen with no work on the user’s behalf. That would be great for users, who would expand their world without working for it. It would also be high value for creators, who would get to play the Hub’s lottery.

Alternatively, you can use this network effect to kickstart from zero.

We’ve seen this happen before with Craigslist. Hub-and-Spoke network effect was the launch motion on Craigslist’s journey to marketplace dominance. The Hub served as a strong initial platform to deliver value to nodes right away. Eventually, the nodes demanded a more active role: a marketplace was a natural evolutionary step.

Why is now the time for Hub-and-Spoke Network Effects?

There’s something big, but perhaps not unexpected, happening on the web right now that favors the Hub-and-Spoke model.

Online networks go through cyclical periods of aggregation and decentralization. AOL and Prodigy were the first to centralize nascent Internet communities in the early 90’s. The Internet decentralized in the late 90s during the first boom and the subsequent winter. It re-centralized with mega-social networks like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, circa 2005-2021.

Now, we are decentralizing once more due to the rise of Web3’s decentralized ethos, and other socio-cultural forces that are driving people to different niches (for better or worse).

Hub-and-Spoke networks thrive with high degrees of familiarity and dense social ties. These are communities where your reputation and/or value really matters. Within these densely connected groups, people really want to be seen as winners. The Hub-and-Spoke network is designed around this psychological impulse.

A well-constructed Hub serves as a shortcut to rewards – in fact, it guarantees “winning” for some users. It makes the promise that other social networks only winked at, absolutely explicit. Those networks implied that you might gain a following or reap a reward over years. The Hub-and-Spoke network effect, instead, signals to users: Use us, and you could be picked, which guarantees status.

You offer tantalizing control over the power laws that have governed the economics of creativity for centuries.

As a Founder, the Hub-and-Spoke network effect is a tool you want in your arsenal.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.