As investors and advisors in over 60 early-marketplace startups, we’ve paid close attention to what it takes to get marketplaces started.

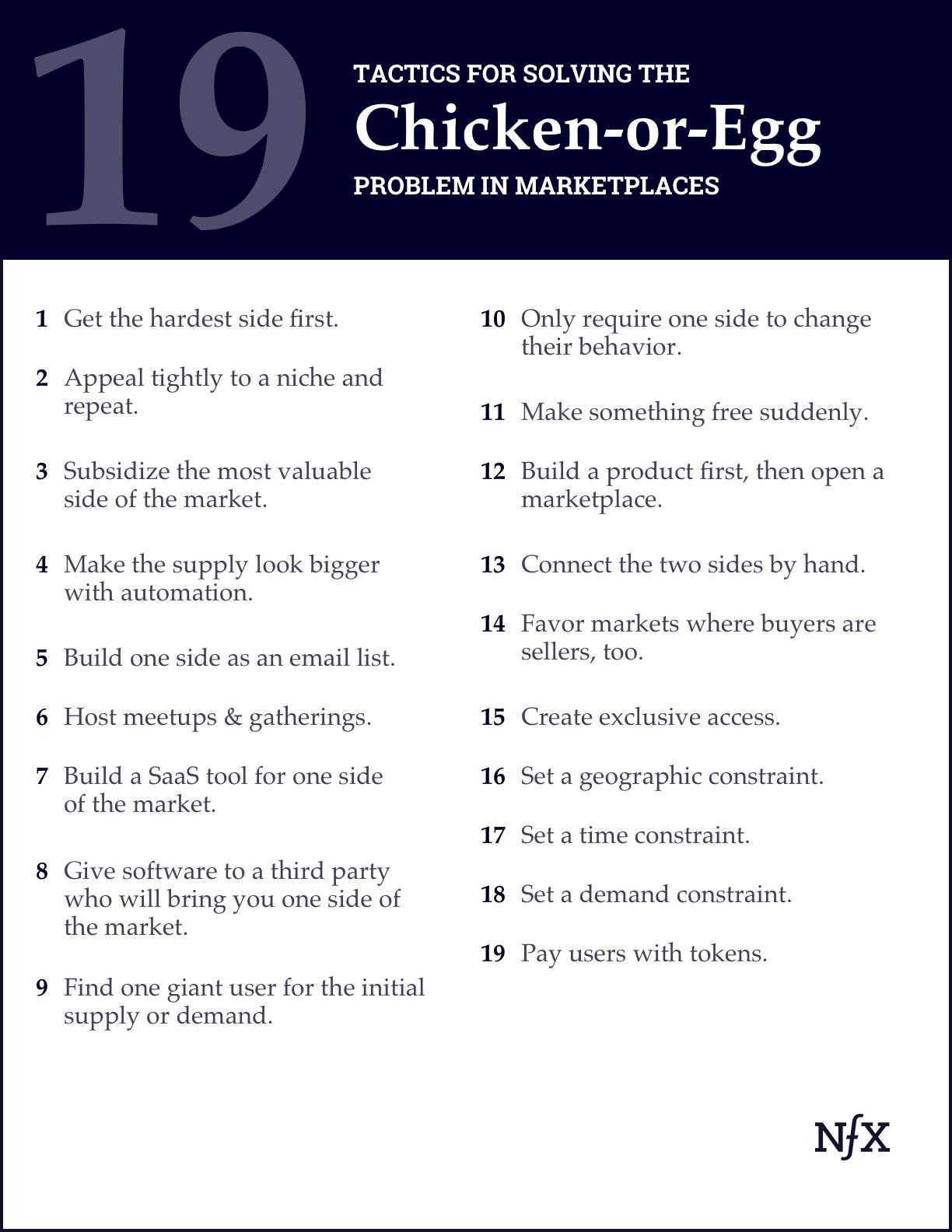

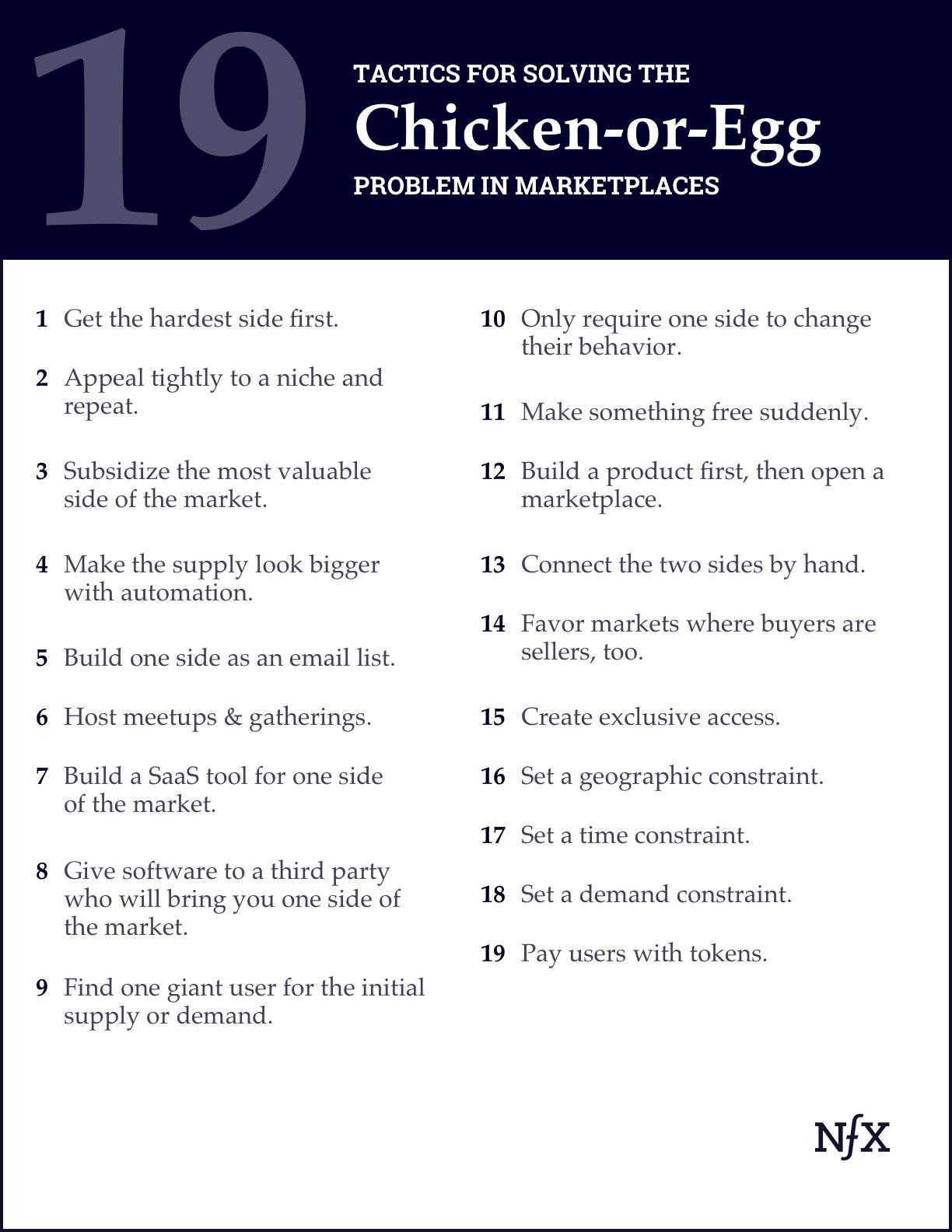

Which comes first, the supply or the demand? Chicken or egg? We’ve noticed at least 19 distinct, executable tactics Founders can use to solve the chicken-or-egg problem.

Tactic 1: Get the hardest side first.

When the harder side (supply or demand) reaches its boiling point of activity, network effects kick in and value will be created organically for the easier side. In most markets, either supply is harder to get to participate in your marketplace or demand is. You can figure that out by testing the sales and onboarding process. Typically, whichever side is hardest is the more valuable, and once you get enough of them, the other side is 2-10X easier to bring onboard.

Examples: Outdoorsy is the RV rental marketplace. They figured out that getting the supply—the RV owners—was the harder side of the market. Once Outdoorsy convinced the RV owners to join their platform, the demand came 5X faster and cheaper, and Outdoorsy became the online mecca for mobile lodging.

Tactic 2: Appeal tightly to a niche and repeat.

Find the small groups in your community that care most about your marketplace—what we at NFX call the “white-hot center”—and go after them. You typically figure this out by going broadly enough to gather data which shows the highest activity.

Examples: eBay first got traction with Beanie Babies. Craigslist started as an email list to Craig’s friends who wanted apartments for rent and jobs. Uber started with “rich bros” getting black cabs in SF. Poshmark started with urban female professionals.

Tactic 3: Subsidize the most valuable side of the market.

Pay cash to the most valuable side of the market—or the most valuable niche within the most valuable side—to join your marketplace.

Examples: Uber initially paid the supply-side—drivers in key cities—to be on their app so that riders always had a car to book. Helix subsidizes the demand-side by covering a portion of the costs of genetic tests. ClassPass paid the supply-side—gyms—upfront cash to join their platform.

Tactic 4: Make the supply look bigger with automation.

This is all about kickstarting the supply-side by aggregating as much data from the web as possible to create a perceived “aura of activity.”

Examples: Yelp, Indeed, and Goodreads all collected data—on local businesses, job postings, and books, respectively—into their platforms to create a useful supply-side without so much activity there at the start.

Tactic 4A: Founders often ask if they should take Tactic 4 to the next level and “fake” activity?

For example, it’s now known that Reddit used fake persona accounts to plant interesting questions. And Paypal built a bot that posed as a human, purchased things on eBay, and insisted on paying with Paypal. These tactics were certainly effective at demonstrating their product’s value to potential users and thus helped the company solve the chicken-or-egg problem. But these tactics probably risked these companies. Had they been caught at the time, they probably would have taken a big hit in the press and social media. Make sure whatever you do, you wouldn’t mind it being on the front page of the Wall Street Journal.

Tactic 5: Build one side as an email list.

An easy and cheap way to start a marketplace, particularly if many of your buyers are also sellers and vice versa.

Examples: This is famously how Craigslist started; Craig started with an email list of friends with a supply of widgets. Threadless also started as an email list.

Tactic 6: Host meetups and gatherings.

It’s tough to scale events. However, at the beginning, they can be effective to generate community, demonstrate activity, and give you direct customer feedback, particularly when you’re loud about it on social.

Examples: Poshmark hosts “Posh Parties” where guests gather and exchange fashion goods. The guests use the Poshmark app to solidify their new, real-world connections. In 2004, Yelp famously threw parties when they were getting going. Attendees went home loving Yelp, and wanting to be members of “Yelp Elite,” the heavy reviewer community.

Tactic 7: Build a SaaS tool for one side of the market.

When you give or sell one side of the marketplace a SaaS tool, it helps lock them in so you have time to attract the other side.

Examples: OpenTable started by building SaaS reservation software for restaurants. Honeybook built software for event planners and other creative professionals to manage their daily proposals, billing, and workflow. StyleSeat built reservation software for hairdressers.

Tactic 8: Give software to a third party who can bring one side of the market.

Examples: Android built software for cell phone manufacturers who, in turn, brought consumer demand. Now Android takes a significant percentage of the app revenue. MySpace gave free profiles to bands who, in turn, brought all their fans to the platform.

Tactic 9: Find one giant user for the initial supply or demand.

Example: Candex supplies software to Siemens who is a big anchor for the demand-side. Siemens then requires its supply vendors to be on the Candex marketplace in order to be paid.

Tactic 10: Only make one side change their behavior.

Example: Square. In 2009, there were perhaps 10 other venture-backed startups trying to own mobile payments. Why did Square win? Because they only made one side—the merchant, supply-side—change their behavior. The demand got to use their credit cards as usual.

Tactic 11: Make something free suddenly.

Taking something that used to cost money and suddenly making it free will drive users to your marketplace.

Examples: Robinhood, whose making trading free, recently raised money at a $5.6B valuation. Napster made music free. Skype made phone calls and video calls free.

Tactic 12: Make a product first, then open a marketplace.

Examples: Salesforce created a CRM tool before opening the Force marketplace platform on top of it years later. Amazon started as a retailer and then opened a marketplace. Now 50% of Amazon’s transactions come from the supply-side of their marketplace instead of the Amazon warehouses. Apple built the first 32 apps in the app store before opening the platform up to developers. SmartRecruiters launched as a SaaS tool for posting jobs before opening a marketplace to sell software to HR departments.

Tactic 13: Connect the two sides by hand.

Examples: In the early days of Zappos, when an order was placed, someone at the company would fulfill the order by hand; they’d drive to the shoe store, buy the shoes, and ship them out. This was critical because it allowed Zappos to manufacture excellent initial transactions. This was also true of eToys and Zenefits (health insurance).

Tactic 14: Favor markets where buyers are sellers too.

Another easy way to overcome the chicken-or-egg problem is to avoid it all together by building a one-sided market.

Examples: The majority of people buying fashion on Poshmark are selling it, too. And the same holds true for Match; the same person doubles as both a “buyer” and a “seller.”

Tactic 15: Create exclusive access.

Restricting access and creating a fear of missing out among the demand or supply can build strong word of mouth and a flood of participation in your marketplace when the idea catches viral fire. However, let’s be honest: it almost never works.

Examples: Gilt, Gmail, and Mailbox.

Tactic 16: Set a geographic constraint.

It’s easier to get a lot of activity going when you limit the surface area of the operation at launch.

Examples: Lyft, Yelp, and Craigslist.

Tactic 17: Set a time constraint.

You can actually program excitement into the marketplace with the help of time constraints.

Examples: At launch, Tophatter only let people bid between 8-9pm PT. During this hour the marketplace felt crowded. The same holds true for HQ Trivia who uses time constraints to manufacture excitement.

Tactic 18: Set a demand constraint.

Examples: Groupon constrained the supply down to one Groupon a day. Fiverr launched by constraining the pricing so everything was five dollars. The idea here is to focus your marketplace on executing a single value proposition well. And it gives everyone a simple reason to be there.

Tactic 19: Pay users with tokens.

Most people don’t want to join a marketplace until everyone is there. If there isn’t any activity on the platform, well, that’s a problem. If you create a token for the marketplace, you can pay people to join, even when there isn’t any activity.

Examples: OpenBazaar and Wemark.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.