Water is three things. Necessary. Ubiquitous. And the same. fucking. thing. inside every bottle.

AI is like water.

Or more specifically, generative AI applications are like bottled water.

Over the last year and a half, we’ve looked at hundreds of generative AI companies on the application layer. Many of them are the exact same under the hood. This is just the reality: there will be 100 teams trying to make the same generative AI application as you are right now. Plus there will be incumbents gunning for your market.

For a long time, tech has been a differentiator among software startups. We thought that if you could build something no one else could, that would be enough to protect you – definitely not forever, but at least for a while.

But what we’re seeing with AI is that tech provides you basically no protection from the start. Tech differentiation in AI is a shrinking moat. (Unless you have something that Karpathy would find enlightening, and if that’s the case, let us know).

For most founders right now, you have to build an entirely new point of view around what differentiation means to you. You are going to need a clear and aggressive perspective on how you’re going to win.

Think distribution. (But incumbents will eat your lunch here too, so the old rules don’t apply.) Think brand. Messaging. Marketing. GTM. Pricing. Customer service. You can’t graft all this on at the end anymore. You’ll need to develop a key insight about how you will be creating value for your end users in a way that no one else can. You’ll need to focus on the heartbeat and emotion of the people you’re building for.

You’ll need to give them a why. Or something they need… or at least something they think they need.

And if people could do it with bottled water, we can do it with the biggest tech breakthrough in at least 14 years.

The Problem: Tech Differentiation is Heading to Zero

Whenever we look at any kind of tech companies, we often ask ourselves: what is the tech differentiator? What’s hard to copy? There are very few ways right now for AI companies to differentiate under the hood. And yet they run this formula for their company and expect it to work: (Data + Model) x some UX = 🎉

But the gig is up. That won’t get you very far. The formula your AI company actually needs has these multipliers:

(Data + Model) x UX x (Distribution + Perceived Value to Customers) = Your new AI MVP

It is basically impossible to differentiate yourself now when it comes to data and model. Sure, there will be some sources of unstructured data that may give you an edge for a little while. But ultimately, data isn’t enough on its own. As for models, most will be interchangeable.

So what’s left?

UX, for starters. In crypto, I used to say that the user experience was like eating glass. No one really figured out a seamless way to bring that tech to a big enough horde of people. The same is true right now for AI, where somewhere someone is going to come up with a way to use AI that blows our minds, and is probably, sort of weird at first. (And it is almost 100% not going to be a chatbot).

Now let’s look at the distribution multiplier. In terms of distribution, incumbents have a built-in advantage. The same AI startup tech stack we see in pitch after pitch has one huge barrier that plays right into incumbents hands: personalizing AI with your users’ data. This is already a tough battle to win because, unless you’re grabbing user data no one else has, you’re lining up to race against an incumbent who is already miles ahead. People log into Instagram daily, or have everything they ever wrote in their company Sharepoint or Google Drive.

One way around this, maybe, is to deliver value outside of the AI solution, and graft it on later. It goes back to part one of our AI Litmus Test: If you took AI out of your pitch deck, is this still a good business?

Finally, we have the perceived value of your company to customers. This is a psychological game, and one where startups have a lot of room to maneuver. You can imbue even the most plentiful, bland material with emotional value, if you get your brand right from the beginning.

Which brings me back to bottled water.

What the Bottled Water Industry Can Teach Us About AI Applications

Every bottle of water contains (mostly) the same thing. But there are approximately 80 brands of bottled water in the United States.

A human being can’t survive without water. But that alone isn’t enough to subsidize the bottled water industry because 90 percent of the tap water in the United States is safe to drink. Yet people still buy bottled water because of strategic marketing, distribution, and cultural tailwinds. Now bottled water is the #1 selling beverage in the US.

That’s because someone took something as ubiquitous as water and made it into an industry. I’d argue that company was Perrier.

In the 1850s, there were a few regional bottled water companies, mostly based around natural springs. These early entrepreneurs focused on the “health benefits” of drinking bottled water versus tap water – a fair comparison at the time when the American public water systems were in development.

But by 1900, that angle was over. Most public water was clean to drink in the United States. As late as 1970, the bottled water industry, if you could even call it that, barely existed. Even after the development of PET, which made plastic bottles far more accessible, most bottled water sold in the US at that time was in gallon jugs for office water coolers.

That status quo remained until Perrier, a languishing French brand, decided to go upmarket. Perrier was mostly sold B2B as a mixer for alcoholic drinks. But in the mid 70s, they began running D2C commercials, positioning the brand as upmarket, sexy (yes really), and a fresher, purer, alternative to tap water. And they didn’t pull any punches – Orson Welles was literally doing the voiceovers.

Side Note: As these thoughts were swirling around in my head, I recently saw some of these early Perrier ads while on a trip in Paris. It’s one of the reasons I couldn’t get the phrase ‘AI is like Water’ out of my head.

Because of that, I’ve wondered if this was a good or bad thing for the AI space, and what it means for founders. The Perrier story, I think, at least shows us a way forward. It’s probably better to be different under the hood, but if you’re not, you have to be insanely memorable, original, and clever. You have to be the kind of person who thinks about making a sexy water commercial before anyone else does.

Perrier’s sales jumped from $3 million in 1975 to $200 million in 1979. In 1992, Nestle acquired Perrier, but the bottled water market was officially (re)born.

The momentum kept going. Between 1988 and 1998, sales increased 144 percent. As the New York Times put it at the time:

“The United States is the world’s largest market for imported water. Water bars in Boston and New York and Los Angeles, often inside health clubs or trendy home-furnishing stores, display bottles from places like Italy, France, Sweden, Wales and Fiji as if they were single-malt Scotch, and charge laughable prices for something that can be gotten out of a faucet…How do they get away with it? Why do we feel the sudden need to pay money for what has always been free?”

By 2001, Coca-Cola and Pepsi both began to use their existing soft drink purification equipment to “purify” tap water. They created two major mid-market brands: Aquafina and Dasani. With those distribution advantages, they claimed a huge market share. Today, they are still among the top two selling brands, even though their taste profiles often rank below competitors’.

So what happened in the bottled water industry? It was a cycle of rebirth. The bottled water industry was dead. It was revived with smart marketing and niche placement. The incumbents came in and crushed much of the competition and acquired the real standouts.

But if you look around again, there are still new bottled water companies popping up following the same pattern. Liquid Death. Chlorophyll water. It’s not like we need more water brands. But more and more are coming to the table with unique stories and value propositions – like Perrier did in the 70s. The branding is just getting weirder. They’re counter positioning. They’re putting water in cans and selling it like energy drinks.

For example, while branding Liquid Death, Founder Mike Cessario described his thought process this way:

“Our brains are wired to just repeat things we’ve seen be successful in the past. You kind of have to trick your brain to come up with a bad idea to truly be thinking in innovative territory.”

Some people worked this playbook and succeeded but there are plenty of examples of companies that failed using the same tactics. Dasani, for example, was pulled from the shelves in the UK after audiences found out it was basically filtered tap water, and it was then shown to contain bromate (a lethal 1-2 punch for the brand). Then there were over-the-top brands like Bling H2O – $55 filtered tap water, which is technically still around, but not a major player in the bottled water space.

The thing about the brand and marketing playbook is that it’s fickle. You can do the same thing as the leader and still fail. You can even be the leader, and fail in a new market (Dasani failed in England). No one likes to break out this playbook, but unfortunately, that’s where we are in the AI application layer.

It’s not a nice takeaway, but it’s the reality. You can either guarantee a loss and not play the brand and marketing game. Or, you can give yourself a small chance of success by playing the game, and seeking other avenues to build your advantage.

One final note here, I’d love to be proven wrong. If you are an AI founder at the application layer with a true technical advantage that makes you untouchable, reach out.

But until then, suffice to say, you have to play this game if you even want to be in the conversation.

An Inflection Point

Of course, bottled water isn’t the tech industry. Isn’t the whole point of investing here that, eventually someone invents something new, defensible, and mind blowing? And isn’t AI that thing?

Yes and no. First the yes: Occasionally a new technology comes along that blows everyone’s mind. That’s why we invest in moonshot technologies, like longevity or space.

But at a certain point every technology will reach an inflection point where the tech itself is no longer the secret sauce. The 1000th match-3 mobile game. The 700th dating app or dieting app or photo app.

This happens because, over time, more people learn how to do these things. New companies emerge that take the technology to the next level. Eventually the core technology becomes so cheap that it’s ubiquitous. And worse, the core experience becomes familiar, and we all know what familiarity breeds.

At that point you need to seek new avenues of differentiation.

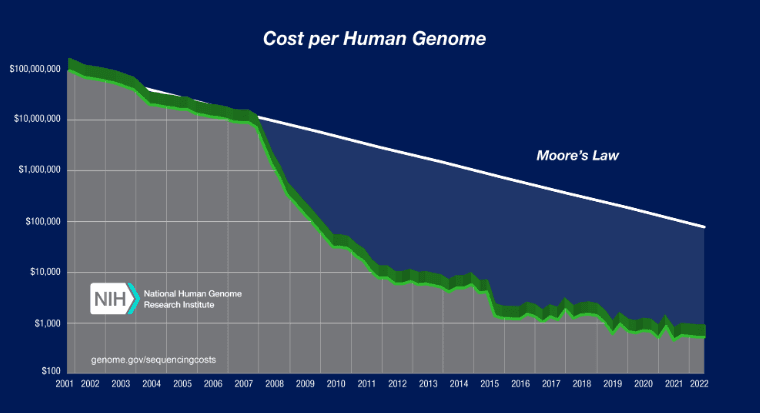

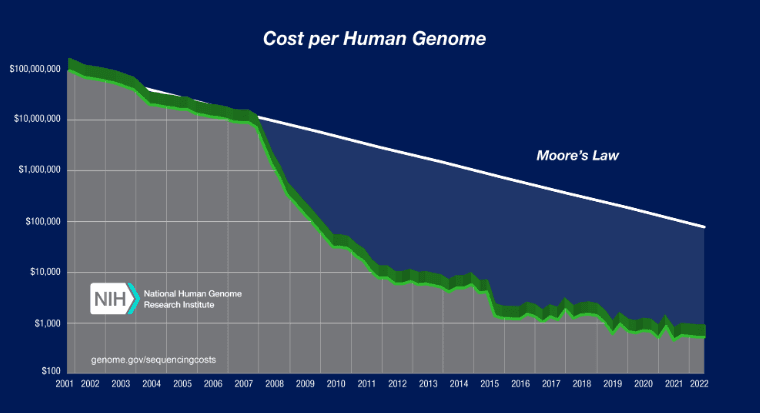

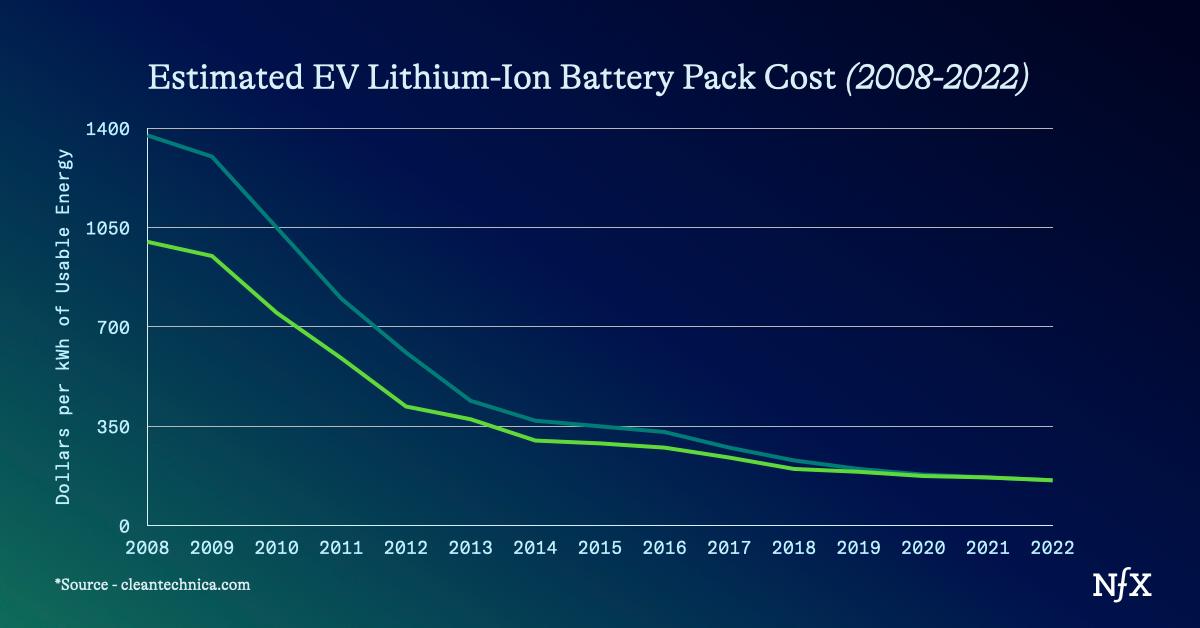

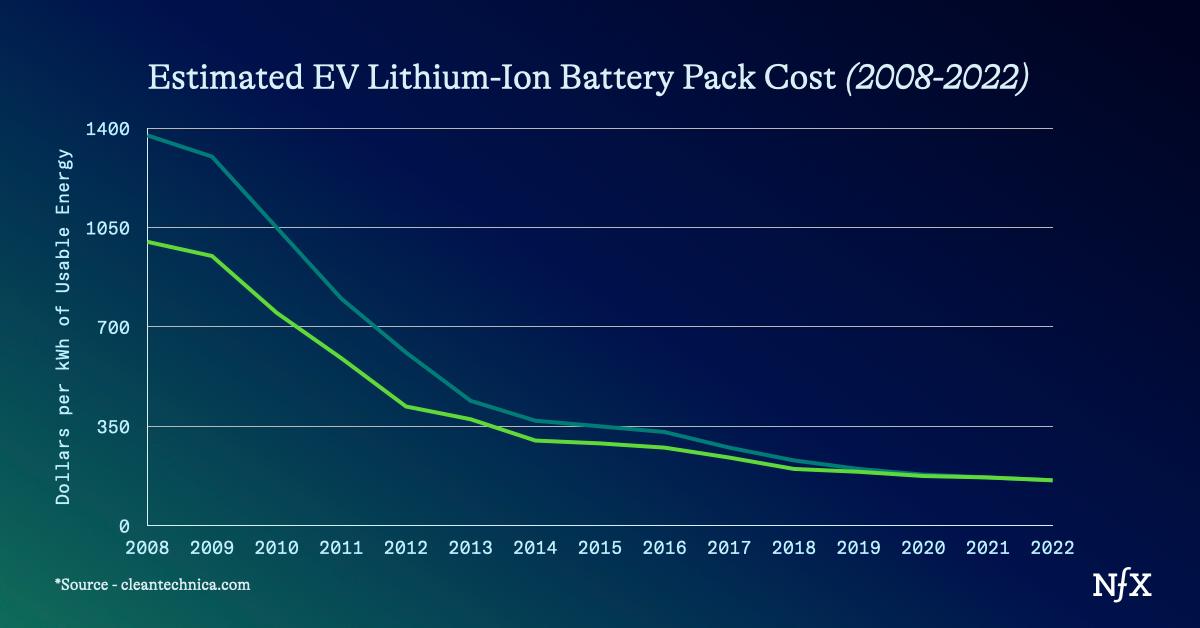

The harder your tech is to copy, the longer it will be until that moment arrives. But it always arrives. It arrived for genome sequencing, where costs have plummeted. It is arriving for batteries for electric vehicles.

And if it happens for those “hard” technologies, it’s definitely going to happen for ones where copy/paste exists and open sourcing is a thing.

When we reach this point, usually one of two things happens.

- An entirely new industry forms on top of this technology. (techbio or electric vehicles)

- Companies double down on new ways to differentiate themselves (i.e. brand in AI)

Both of these situations can actually be good for startups that understand they’ve reached the inflection point.

For example, no company in techbio uses genome sequencing tech as their core differentiator, but they use that tech combined with other things to solve many new problems. They took door #1.

We actually saw the crypto industry take door #2. Initially, we used to say that which protocol you build on top of was the most important thing. But over time, as more protocols emerged, they began to converge around a mean of utility. They were very similar. So what differentiated them? How you phrased your tech. Which builders you got on board very early.

That transition from tech differentiation to branding was even more clear at the application layer in crypto. For any NFT project, that’s all it really was. Brand, on top of technology that was becoming ubiquitous. If you look at some of the most powerful brands in NFTs, like Bored Apes, those brands still hold value today. (A Bored Ape is still worth about $100 grand).

That’s all brand, marketing and distribution. It has little to do with the protocol underneath.

Is AI Being “Like Water” Actually That Bad?

Both of those situations can actually good for startups. Either a whole new industry forms on top of the new innovation. Or, you double down on brand, and break out the bottled water playbook.

So is AI being “like water” actually that bad?

It’s only bad if you don’t realize what’s happening. The problem with AI is that we are already at the diffusion point. We got the equivalent of the $200 battery or the $100 genome sequence basically immediately. You had to identify doors #1 and #2 months ago and run through. Lots of companies haven’t recognized this transition point yet.

Once you realize that the underlying tech is no longer your differentiator, you start asking yourself different questions, seeking new niches, and focusing on new points of differentiation.

Thanks to Drew Beller for his feedback on this framework.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.