“Doubt what you know, be curious about what you don’t, and update your views based on new data.”

This is the general maxim underlying the classical scientific method. It is also the one mental model universal to most successful startup Founders. Thinking from first principles, treating ideas as testable hypotheses, and cultivating a challenger network is what the best Founders do.

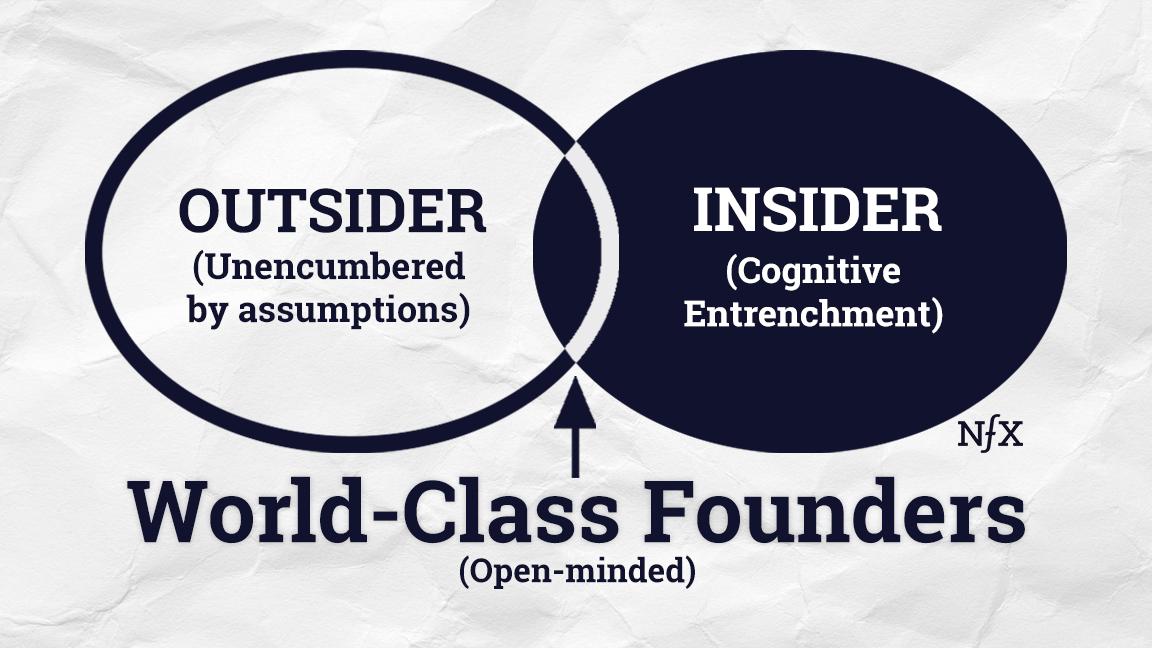

But Founders and VCs also tend to over-index on experience — and experience is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it’s difficult to have good ideas when you don’t understand the problem well enough to try to solve it. But on the other end of the spectrum, if you have extensive experience or expertise, you run the risk of cognitive entrenchment. When Founders get too attached to their existing patterns of thinking, they become prisoners of their own prototypes.

The best Founders we see at NFX know when to rethink the assumptions that they and everybody else have made about an area, technology, or market. This unlocks breakthrough thinking in order to make the seemingly impossible, possible.

I recently got together with organizational psychologist and bestselling author Adam Grant to discuss his new book, Think Again, about the counterintuitive and competitive advantages of rethinking.

Today, Adam and I share the frameworks for:

- Rethinking vs. Contrarian Thinking

- Techniques from the World’s Best Superforecasters

- Jeff Bezos’s 2×2 Decision Framework

- The Top Killers of Co-founder Relationships

- Why Confident Humility Is A Founder Superpower

- & more

The world is changing faster than it ever did before. Founders who can adjust their beliefs and rethink what they know as the world around them changes will see new opportunities that others miss.

Do You Think Like A Preacher, Prosecutor, Politician, or Scientist?

- Founders need to be great learners and they need to be fast learners.

- Without question, almost every great Founder that I’ve met has excelled at questioning assumptions. I think that’s where disruption begins.

- Where we run into trouble though is when we question other people’s assumptions, but struggle to question our own.

- Basically, when people form judgments, make decisions, think or communicate, they tend to slip into three mindsets that sometimes lead them in the wrong direction:

-

- When you’re in preacher mode, you already believe that you’ve found the truth and your job is to proselytize it to everyone else.

- When you’re in prosecutor mode, it’s the reverse. You’re trying to prove everyone else wrong and win your case. My worry about people who score high in preacher or prosecutor mode is that they don’t rethink their beliefs and opinions and assumptions often enough. If I’m right and everybody else is wrong, then I can stick to my guns.

- Politician mode is a little more flexible because you’re trying to campaign for an audience’s approval. You might be trying to convince a VC to bet on your startup. You could be trying to sell your board on you being the perfect candidate to keep running the company. And that means you’re going to cater to whatever you think your audience wants to hear. The problem with that though is that you’re often changing your mind at the wrong times for the wrong reasons. You’re just saying what you think the audience wants to hear, but you’re not actually adjusting your beliefs at all.

- I think we’re generally better off if we are open-minded with a fourth mindset, scientist mode. When you have an idea, you’re not sure if it’s going to change the world so you’re interested in finding out. “Okay, I have this hypothesis. Is it true or not? And what data do I need? What observations do I need to make in order to figure out whether it’s true or false?”

- The world is changing faster than it ever did before. If you’re not willing to adjust your beliefs as the world around you changes then you’re going to stand still and other people are going to end up seizing the opportunities that you miss.

- There’s a great experiment that I think demonstrates this beautifully. It’s with over 100 startup founders in Italy. They’re all pre-revenue. The control group goes through a couple of months of entrepreneurship education. They get to build a business plan, figure out what they want their product to look like, and formulate a strategy.

- The experimental group does the exact same education only they’re given this lens to think about their startup as if they were scientists. They’re taught that whatever strategy they have, that’s just a theory and they should try to build a bunch of testable hypotheses around it.

- They should treat their customer interviews as initial data points. They should say, “Okay, you know what? When I launch my minimum viable product, that’s my first experiment. And my job is to collect a bunch of evidence about whether my hypotheses were supported or falsified.”

- Those Founders, over the course of a year, the ones who were in the control group, averaged under $300 in revenue. The ones who are taught to think like scientists averaged over $12,000 in revenue.

- If we look at why the big difference between the two groups is that the scientific thinking group pivots significantly more often. They’re more than twice as likely to make a major shift in their vision or their strategy.

- Instead of getting locked in on one product idea or one way of addressing a market, they say, “All right, I’ve got to stay flexible and figure out what’s actually going to work and build a customer base.”

- To me, this is some of the most compelling evidence that I’ve seen that at least some of the principles of lean startups were on target.

Superforecasting Starts with One Simple Technique

- The best data that I’ve seen on decision making in messy situations comes from studies of superforecasters.

- In superforecasting tournaments, what people do is compete to try to predict future world events. You might be asked six months from now, is the Euro going to go up or down? Or, in four years, who’s going to be the Republican challenger to President Joe Biden?

- And you’re scored not only on how accurate you are but also on how calibrated your confidence is. So, in an ideal case, you were very confident about the predictions you were right about, and you had wide confidence intervals, a lot of uncertainty, about the predictions you were wrong about.

- If you look at the research on superforecasters, what you see is the best predictors of their accuracy are not the usual suspects behind success. They’re not grit. They’re not intelligence.

- The single strongest predictor, three times more powerful than cognitive ability or IQ, is how often they rethink their forecasts.

- The average forecaster in a tournament will do about two updates. The average superforecaster, the best of the best, makes four updates.

- You don’t have to be pivoting every day. It’s about saying, “Okay, I just want to rethink some of my fundamental assumptions a little bit more often than my peers might or than my instincts might tell me to.”

- I think there’s a sweet spot that probably varies by industry. It probably varies by the lifecycle of your firm too.

Jeff Bezos’s 2×2 Matrix for Decision Making

- I had an interesting conversation with Jeff Bezos a couple of years ago when I asked him how he decides when to rethink a decision.

- He said, “If this is a decision that’s highly consequential and irreversible, then I’m going to keep myself open to rethinking as long as possible because once I’ve made the investment, I can’t undo it and the stakes are really high. But if it’s reversible or if I think it’s inconsequential, then I’m going to act quickly, and over time, I know I’ll have lots of opportunities to rethink in reaction to the feedback that I get in response to the data.”

- I thought that was a helpful framework.

- What I’ve tried to do now is draw that 2×2 and say, “Okay, for the decision I have to make,” when I’m involved in startups, either as an investor or an advisor or occasionally in an entrepreneurial role, I’ll look at, “Is it consequential? Is it reversible?”

- I try to do my rethinking upfront if it’s consequential and irreversible, and I’m willing to do the rest of it on the backend if it’s inconsequential and reversible.

- Startup pivots are often the ultimate irreversible decision, but there are so many day-to-day decisions that need to be made.

Rethinking vs. Contrarian Thinking

- I think about being contrarian as betting against consensus, which is obviously high risk, high return, because it’s probably more often than not consensus is right.

- I think about rethinking as something that you do independent of what other people believe.

- The worry I have with contrarian thinking is that it has to contrast with the crowd. You’re defying some norm or some widely shared view. I think in a lot of cases, that is what rethinking involves too.

- Other people have made an assumption that maybe they don’t even realize they’re making, they’re taking it for granted, and you need to question it.

- There’s actually a term for why that happens among experienced people. It’s called cognitive entrenchment, and it’s the problem that you run into if you have a wealth of knowledge in a domain or deep expertise. You no longer look at the problem with a beginner’s mind or with fresh eyes.

- In that sense, rethinking and contrarian thinking are very similar. At the same time though, there might be times when you need to rethink your assumptions to get in line with the crowd, to follow the norm, to go in the direction that most people are going.

- If your default is just to be contrarian, you’re probably going to miss out on a lot of good ideas that other people have already decided are good ideas.

- You don’t have to reject every single norm when it comes to how to hire, how to promote people, how to compensate people. I think generally speaking Founders are better off if they’re original in some areas and very conventional in others.

- As Keith Rabois said in a recent NFX podcast, only after you master the rules do you get to violate them.

Operate With Confident Humility

- Confidence and humility can go hand in hand. They’re not opposites.

- You can be confident in your abilities as a Founder while having lots of doubt about your knowledge and skills and your tools and strategies.

- You can be confident in your vision while having just a huge amount of uncertainty about your plan for how to execute that vision effectively. You can be confident in your team, but be full of doubts about whether you’re actually entering the right market. We could make a long list of the ways that confidence could go hand in hand with humility.

Sarah Blakely & Reid Hoffman

- I remember asking both Sarah Blakely and Reid Hoffman how they had the confidence to go all-in for their first startups.

- In Sarah’s case, “How in the world did you know that you could build Spanx when you’d never worked in fashion or retail? You didn’t really have much of a business background.”

- And then in Reid’s case, “How did you know you were ready to start LinkedIn when, okay, you’d worked at PayPal, but building an online social network for professionals, that’s not exactly something you had a lot of expertise in, not a lot of independent entrepreneurship in your history.”

- They both told me a version of the same thing. “I didn’t have any confidence in my ability to solve these problems today, but I had confidence in my ability to learn and figure it out tomorrow.” And I think seeing yourself as a learner is at the very heart of confident humility.

- You can say, “Okay, you know what? I’ve got some capacities that I’m excited about. I have conviction in my ability to grow, but I also know there’s a lot I don’t know yet and that I need to learn in order to achieve my goals.”

- It’s pretty hard to start a startup if you’re not confident that you’re onto something important, either that the problem matters or you have a novel and compelling solution.

“Make a list of 10 or 12 different ways the world might look, and then consider the strategy.”

- Founders should try this technique I learned from a superforecaster named John Pierre Biggam, who is arguably one of the world’s most accurate superforecasters. What John Pierre does before he makes a prediction is he makes a list of the conditions under which he would change his mind.

- This is especially powerful to think about in the wake of this pandemic because I think what a lot of people do, I’ve watched countless Founders say this, “Okay, here’s my thesis for what the world is going to look like in three to five years and given that, here’s my strategy.”

- What a superforecaster like John Pierre will do is make a list of 10 or 12 different ways that the world might look and then consider the strategy that will be effective in each of them and then choose the strategy that’s robust across as many possible worlds as he can.

- I don’t think we do enough of that anticipation. I don’t think we spend enough time saying, “Okay, you know what? Let me figure out all the possible conditions that might hold. Let me find a strategy that could work across seven or eight worlds as opposed to just one or two. And if I’m not in one of those worlds, that’s a clear indication that I need to rethink a major assumption.”

- In the organizational psychology world, not using this superforecasting technique often results in what we call escalation of commitment to a losing course of action.

- How many Founders have you watched fall into an escalation trap where they make an initial commitment of time, money, and energy, it doesn’t pay off, and then instead of cutting their losses, they say, “Well, I’ve got to invest even more to prove to myself and everyone else that this was an ingenious idea.”

The De-Escalation of Commitment

- When you’re looking to counter the escalation of commitment, it’s helpful to separate the initial decision-makers from the later decision evaluators.

- If you’re the person who dreamed up the vision and locked in on the strategy, you are the least qualified person to decide whether it’s time to pivot, because you’ve already gotten yourself invested in justifying your prior choices.

- We are remarkably skilled at rationalizing. We can always find a long list of reasons to justify the choices we’ve made in the past.

- What you want is somebody with an independent opinion to come in and take a look at it and say, “Okay, let’s try to write off the sunk costs and let’s ask, ‘What would we do if today is the beginning of our startup?'”

- One of the thought experiments that often gets recommended in this realm is to say, “Okay, let’s imagine I got fired as the CEO. What are the first three major changes that the new CEO would make not being attached to my commitments? Now, why don’t I become that CEO and make those changes?”

Challenge Networks > Support Networks

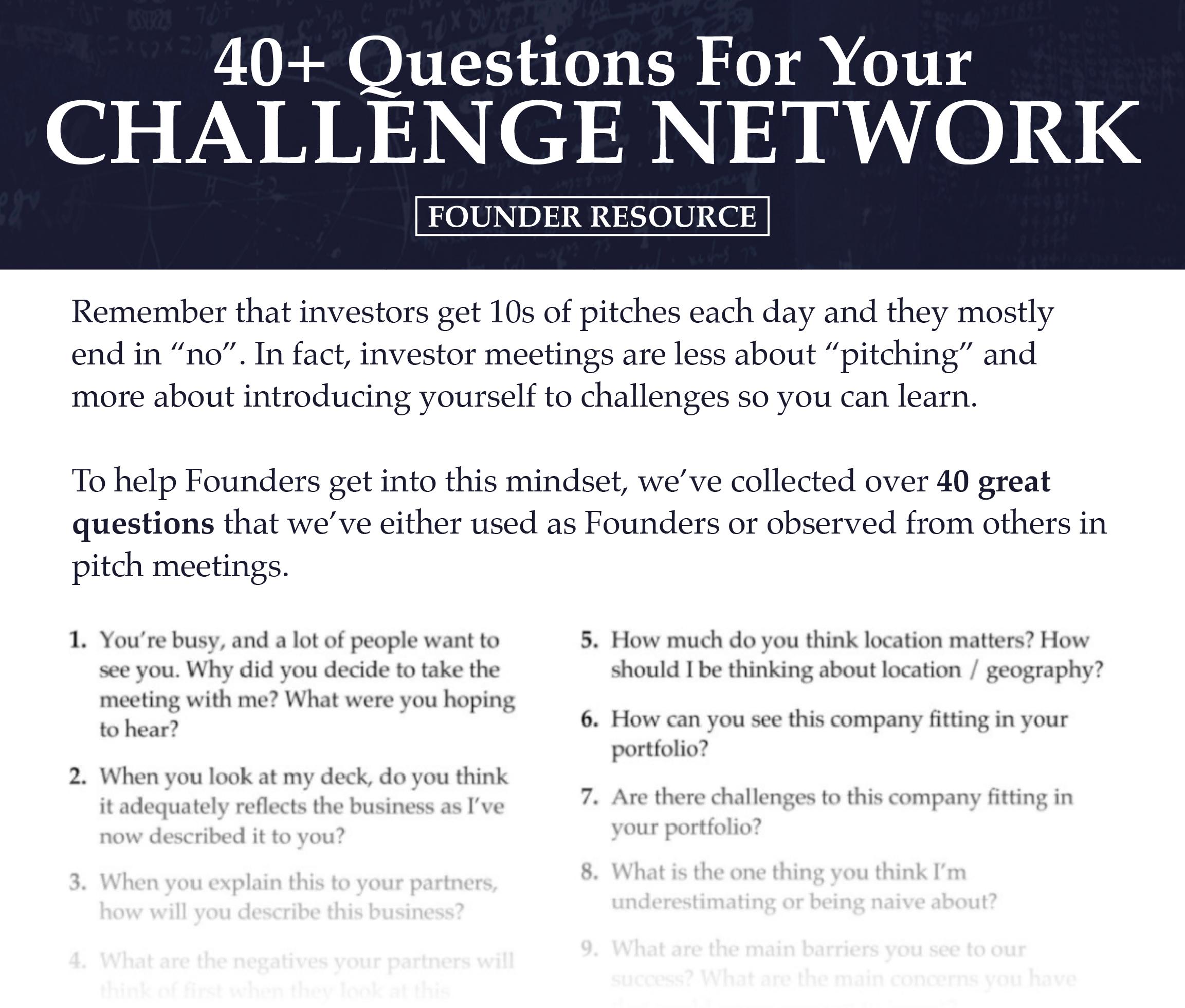

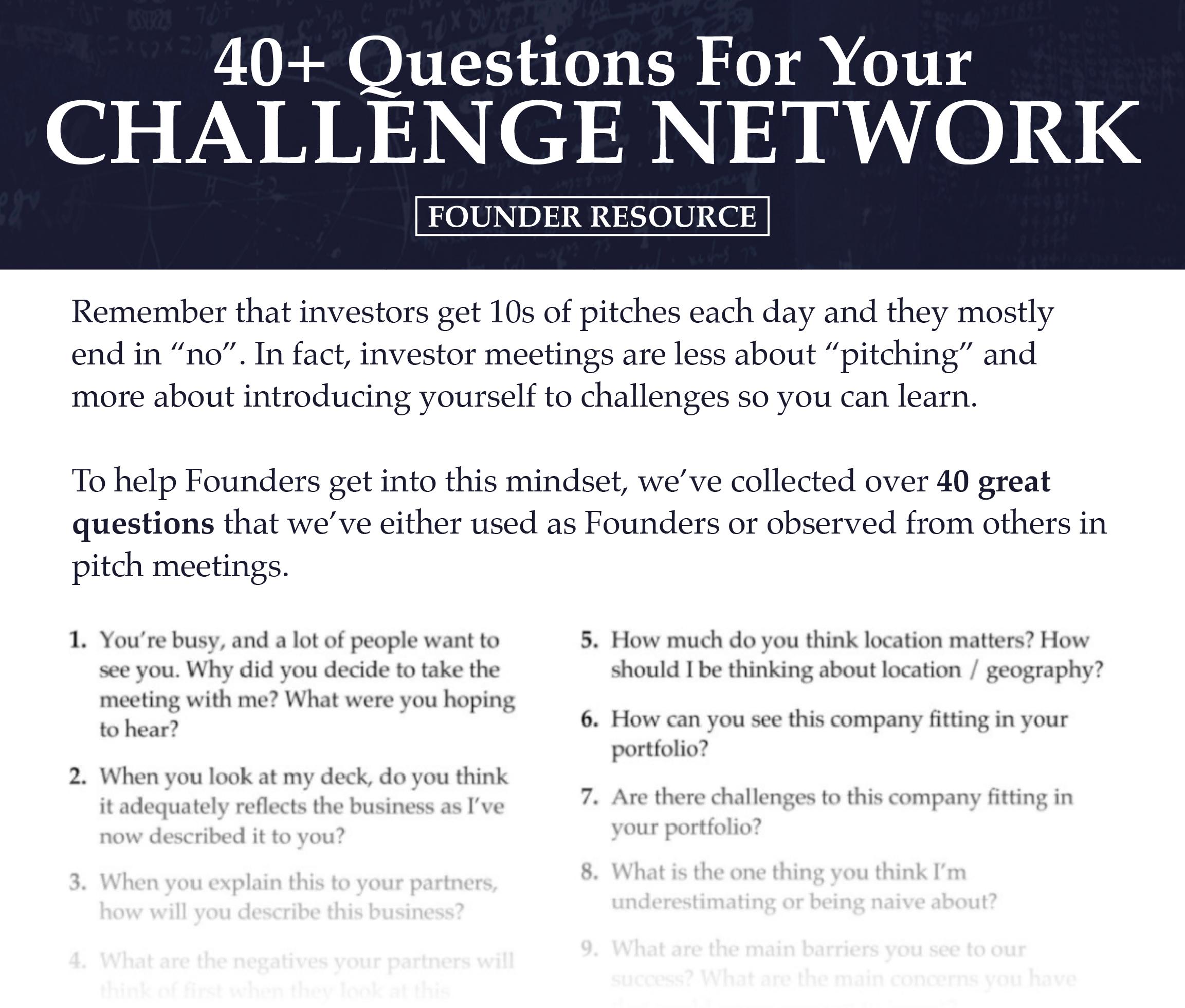

- It makes a big difference if you can walk into a pitch meeting and say, “You know what? I could see these people as critics who are threatening my future success, or I can see these people as teachers who are challenging my thinking and are here to teach me something new.”

- Every Founder I know has a great support network. A group of people who are willing to help them out and cheerlead for them and encourage them when maybe the chips are down.

- I believe we also need a challenge network, which is a group of thoughtful critics who hold us to the highest possible standards and help us see the holes in our own thinking.

- When you go and pitch a startup, you are introducing yourself to a whole new challenge network. A group of people who are going to find every flaw in your ideas. If you look at that and say, “Okay, this is something that’s going to either just crush my ego or I’m going to feel like a failure,” then your natural response is going to be defensiveness.

- As opposed to, if you come in and say, “You know what? Every start-up has flaws. These people that I’m meeting with, their job is to find them so they can help me fix them or hold up a mirror so I can see them more clearly and fix them myself.”

- Now, I don’t see the VCs that I’m going to pitch as adversaries, I actually see them as coaches, and I think that mindset shift can make a huge difference.

- Sheila Keen and Doug Stone have written about a pretty helpful technique for taking critical feedback when it comes. They recommend, “When somebody tells you that they’re not going to invest in your idea, or they don’t think it’s going to make it, that’s a first score that you’ve been given. You can’t undo that first score. They’ve already made a judgment that your idea is not investible or it’s not a fit for them right now. The best thing you can do is try to ace the second score, which is how well did you take the first score?”

- I’ve watched a few Founders turn that around. Instead of arguing with the investor, they say, “You know what? That’s a really good point. If what you say is true, how do you think I should re-imagine what my mission is or what my strategy is?”

- And in rare cases, that’s actually gotten the investor excited, then they start to brainstorm together. Now, they’re co-constructing this idea for how to pick a better problem or come up with a better solution to the problem that’s been identified.

- I don’t see a lot of entrepreneurs do that on Shark Tank, but I think it might be a missed opportunity in some cases.

“Here are the three reasons why you should not invest in my company.”

- There’s a lot to be said for the power of constraints. I think sometimes there’s even value in placing them on yourself.

- I met an entrepreneur a few years ago, Rufus Griscom, who would come into startup pitch meetings and say, “Here are the three reasons why you should not invest in my company.”

- He eventually sold his company after he got investment that way.

- He sold his company, by saying, “Here are the five reasons you should not buy my company.” It was actually a slide in the pitch deck.

- I think partially it seemed like a marketing gimmick. People were intrigued. It was different. He was clearly a non-conformist who was rethinking how you pitch your ideas.

- Some of the investors tried to educate him along the way, saying, “Rufus, your job is actually to tell me why I should invest, not why I shouldn’t. I don’t think you understand what a pitch is all about.”

- But the more interesting thing was that Rufus was showing his confident humility. He was saying, “I believe enough in the strengths of this startup that I don’t have to hide the weaknesses. I think all the upsides outweigh the downsides.”

- He also recognized that the investors were going to find the flaws in his company anyway. He said, “All right, I might as well get credit for having the foresight and the integrity to point them out myself.”

- Instead of having these ‘gotcha’ moments where a VC says, “All right, you know what? This is doomed.” I can say, “I realize I have this roadblock and I would love to talk with you about how to overcome it.” And again, then you have a collaborator instead of a competitor talking with you.

Are you trying to prove or improve yourself?

- The question that I’ve tried to ask myself in tough situations, and sometimes I’ve done it more effectively than others is, “Okay. What’s my goal here? Am I trying to prove myself or am I trying to improve myself?”

- That’s come in handy, the mentality of seeing yourself as a learner. It’s motivated me in some situations to say, “All right, this is time to rethink my fundamental approach.”

- So, for example, when my agent told me to throw out a manuscript draft for one of my books, he said something that really stuck with me. “I want you to write like you teach, not like you write journal articles.”

- It was a light bulb moment because I realized I had already spent a decade learning how to communicate ideas for an audience that wasn’t reading boring academic journal articles. I just needed to figure out how to put what I did in the classroom on the page. I’ve written differently ever since I got that feedback.

Top Killers of Co-founder Relationships

- I think the inability to have constructive conflict has to be high on the list, if not number one on the list.

- There’s some evidence actually that if you look at Founders who are friends, there are some advantages but the problem is that liking someone is not necessarily a proxy for liking working with that person or collaborating effectively with that person.

- One of the ways that the co-founders get in trouble when working with their friends is they shy away from having difficult conversations because they don’t want to hurt each other’s feelings. They don’t want to damage the friendship.

- Sometimes the trust between them is put on a pedestal and they decide they won’t do anything to jeopardize that. Running a successful business starts to take a back seat. Of course, it’s a false dichotomy.

- If you have trust in a relationship, then you can tell the other person the truth. They will recognize that it’s coming from a good place.

- You’re actually trying to help solve a problem or work out an issue as opposed to criticizing them or judging them in some way.

Task Conflict vs. Relationship Conflict

- There’s this distinction that I think every Founder should understand between what’s called task conflict and relationship conflict.

- Relationship conflict is personal and emotional. For example, I think the world would be a better place if you didn’t exist, or at least my world would be a better place if I didn’t have to deal with you. It’s not surprising when that ends up undermining the effectiveness of startup teams.

- But there’s another kind of conflict that can be productive. It’s called task conflict, and that’s when we’re disagreeing about ideas. We have a clash about what our strategy should be or what our vision should be or where our product roadmap should go. Those kinds of tasks conflicts the data suggest are especially important to have early on.

- If you want to come up with creative ideas and if you want to make a thoughtful decision, commit early to task conflict. Because if you don’t, you’re committing to groupthink and saying, “We might have different opinions in the room, but we’re all going to keep those to ourselves and not learn from each other.”

- One of the keys for Founders to figure out is how to work together effectively. How can you have task conflicts without them spilling over into relationship conflict?

- It’s helpful to frame a disagreement as a debate rather than an argument. I think the simple reason for this is that we all have a mental model for what a feisty debate looks like. We know we’re not supposed to take it personally. It’s intellectual, not emotional.

- At the same time, sometimes I worry that if you come in with a debate mindset, the goal is for someone to be right, and someone else to be wrong, as opposed to saying, “We disagree. Maybe we’re both wrong. Maybe there’s another possibility that we haven’t seen.”

- In fact, if you look at what separates the failed decisions in organizations from the successful ones, the clearest indicator is that failed decisions only considered two options. Just considering a third option was enough to increase the probability that you would land on a wiser choice in the long term.

- Anytime I sit down with Founders and they’re playing tug of war and trying to figure out who’s right, I ask, “Okay, what’s the perspective that neither of you has considered yet?”

Settlers, Pioneers, and Cool Technology

- One of the things that just mystifies me is how obsessed people are with cool technology. I don’t care how brilliant your technological solution is if there are no customers for it. If there’s not a potential market, it’s not going to go anywhere.

- Let’s take music, for example. My impression is that Silicon Valley dismissed it because the tech wasn’t revolutionary. You’re not building something that never existed before. So why should you do it?

- The reality is that there’s this tremendous demand for music. It wasn’t going anywhere. The iPod should have taught us that.

- What we were missing was a good set of solutions for people to get access to the music that they love. Spotify solved that problem.

- Thinking about customer demand before thinking about the brilliance of the technology might be a course correct for some Founders and investors.

- Tesla is another example. Many of the VCs I know thought they were already an established market with so many barriers to entry and fixed costs. They couldn’t imagine accumulating the capital to do it.

- There’s surprisingly this myth of the first-mover advantage. My read of the evidence is that more often than not, it’s actually the fast followers that are successful.

- All the work you have to do to create a market ends up putting you in an escalation commitment situation. You’re stuck to the initial investments that you’ve made. Whereas if you let somebody else create the market and then you analyze what’s working and what’s not, you have an opportunity to jump in and improve it.

- Looking back, almost all of the tech companies that have fundamentally changed their landscapes were not the first movers. Google did not invent search. Facebook did not invent social media. Apple did not invent the personal computer. They are all improvers, not first movers.

- I wonder if we need to walk away from the pioneer mentality and say, “There’s nothing wrong with being a settler in a land that somebody else discovered.”

Creativity Combinations

- Experience like almost everything else in life is a double-edged sword. If you look at the relationship between experience and innovation, my read of the best evidence available is that it’s curvilinear. So if you have no experience whatsoever in a domain, very little knowledge, it’s hard to influence that domain or come up with a creative idea because you don’t understand the problem well enough to try to solve it.

- But if you go to the other end of that spectrum and you have extensive experience or expertise, that’s when we see cognitive entrenchment start to kick in. They become prisoners of their own prototypes. They get too attached to doing things the way they’ve always been done.

- There seems to be a bit of a sweet spot in the middle, where you know enough to understand the domain but you’re also not an “expert.”

- It’s that outsider perspective that’s so important. You have enough distance to say, “All right, you know what? Maybe we could rethink a lot of the assumptions that everybody else in this area has made.”

- This doesn’t mean that you should limit the amount of experience you get in a domain or you should try to put a ceiling on your expertise.

- What it means is that when you get to a certain level of experience or expertise, it’s time to diversify.

- That means you’ll want to immerse yourself in another industry or a different culture. You’ll want to bring someone onto your team who has a very fresh perspective and doesn’t know your industry well. See what kinds of assumptions they question and what curiosities they bring to the table.

“Creativity is mostly just putting old things in new combinations and new things in old combinations.”

Hunches, Not Truths. Learn Something From Everyone. Look for Better Practices.

1. First, start treating your ideas and opinions as hunches rather than truths and say, “Okay, I’ve just landed on an idea. I wonder if it’s accurate or not. Let me go out and explore it.”

2. A second step is just to recognize that one of the marks of being a lifelong learner is knowing that you can learn something from every single person that you meet. I think we probably underutilize the people in our lives as sources of new perspectives.

Maybe there’s value in running my startup idea by somebody who’s completely foreign to my industry to see:

- Can I explain it to them?

- What do they find interesting about it? What questions and concerns do they have? Did I discover a way to broaden my market or to adjust my approach a little bit?

There’s always something to be learned. I think the moment you write someone off as not knowledgeable is the moment that you decide you’re not interested in a fresh perspective anymore.

3. The third thing is that we need to build cultures of open-mindedness. To me, one of the biggest enemies of openness is the idea of best practices. The moment you declare a best practice, you are done rethinking it. You’ve already found the perfect routine, the ideal way to do things.

It’s subtle, but I think looking for better practices keeps us open to re-imagining and reinventing.

You can listen to the podcast conversation here.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.