Airbnb. Doordash. Uber. Lyft. Fiverr. We’re in the golden age of marketplace businesses. These highly anticipated marketplace IPOs, now over $200B+ in total market cap value, are demonstrating the power of the 2-sided marketplace network effect.

Their successes, however, are many years in the making. Founders rarely get to hear the inside story of building a massive marketplace business from idea to IPO. Today we analyze the core startup decisions you need to make in the early days about your market, product, pricing and customers — and how those early decisions define your roadmap for the next 10 years or more.

This essay unpacks my recent NFX podcast conversation with Micha Kaufman, the Founder and CEO of Fiverr (FVRR). Fiverr’s stock price has soared since their 2019 IPO — posting an impressive 797% growth since last year — but this conversation makes evident that their DNA for success was set from day one.

Excerpted below, Micha gives us access to the early days at Fiverr and what startup lessons he learned while leading one of the world’s biggest marketplaces, including:

- When You’re Told The Idea Is Too Crazy To Work

- A 3-Part Framework For Finding The Right Market

- Fiverr’s Epiphany: Productizing Services

- Reverse Your Storytelling In Order To Build The Best v1

- Supply Generates Demand: The Fiverr Law of Business

- Doing The Opposite Of What You’re Told For A Go-To-Market Strategy

- Keeping “Startup Speed” Even As A Public Company

- & more

This is a tremendous resource for early-stage Founders everywhere as they make key decisions that will set their startups into motion.

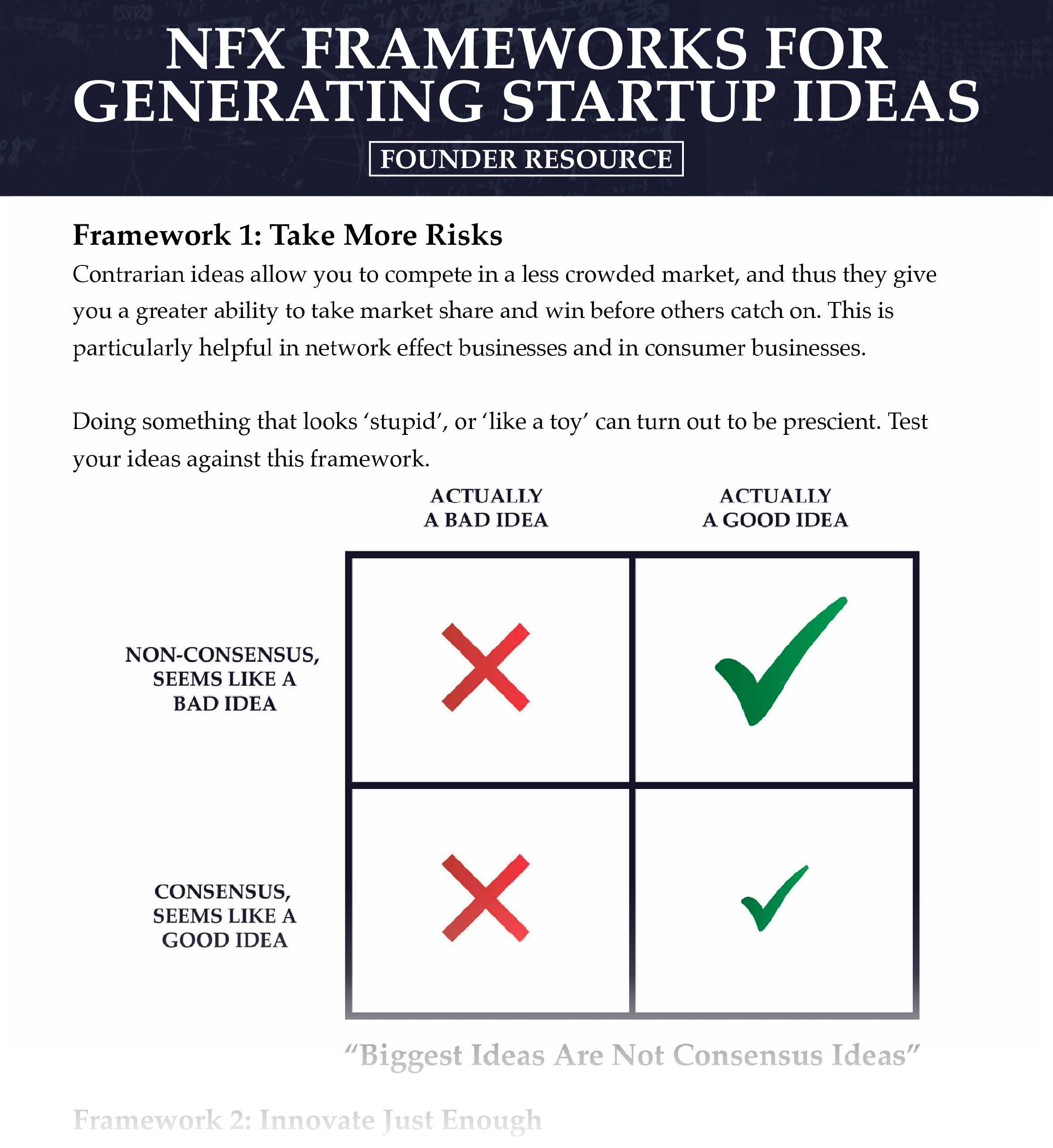

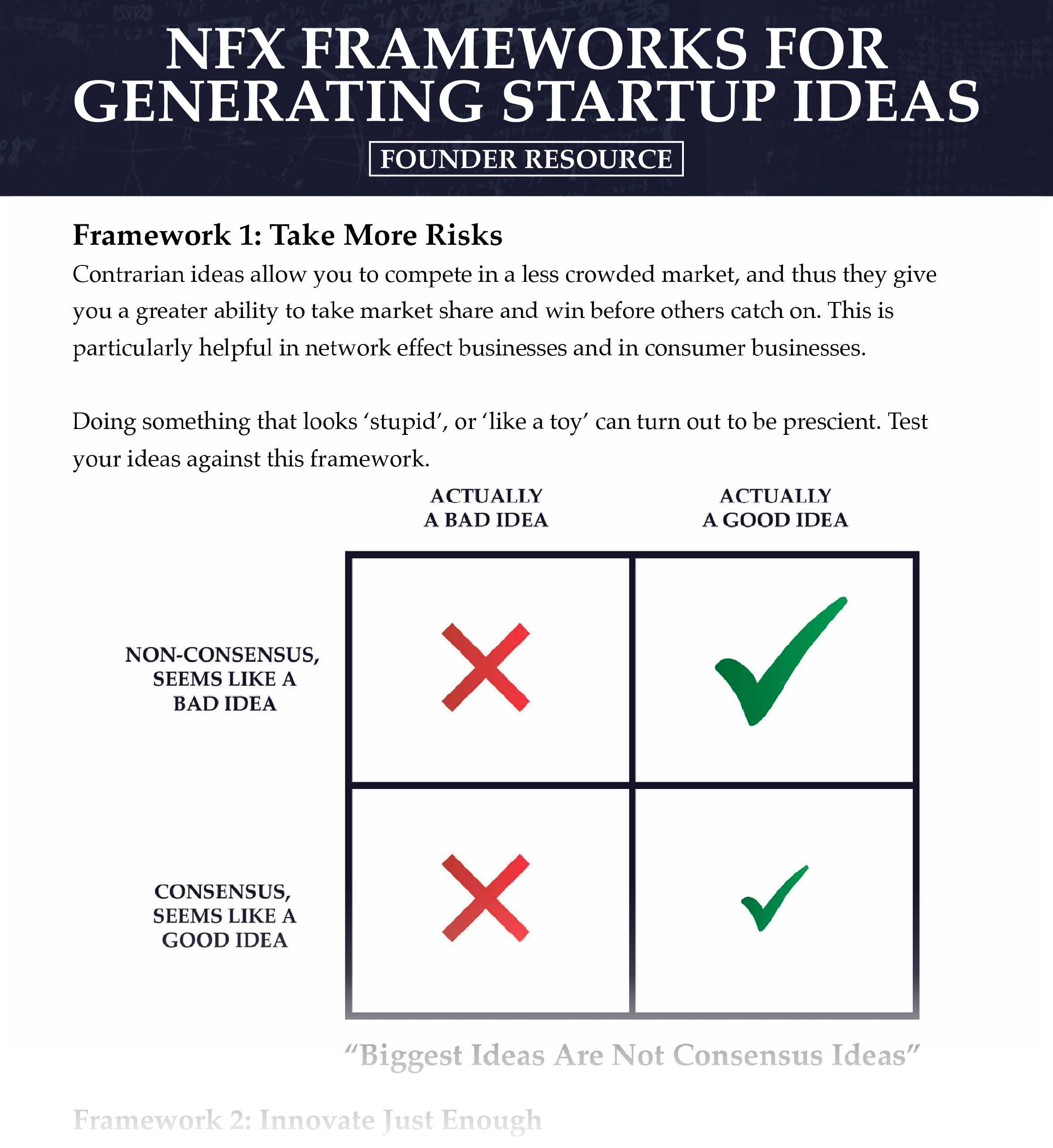

1. When You’re Told The Idea Is Too Crazy To Work

The best way to bypass doubters in the beginning is to bootstrap, then you don’t need to persuade anyone.

- That’s actually what we did. For the eight or nine months that it took to build Fiverr, including the launch and the first three or four months of operations, we were self-funded.

- The truth is that probably the first 10 or 20 people I told this idea to told me that this was either too crazy to work or just stupid, which to be honest, just fueled me more.

- I thought that people couldn’t really envision what this could be. It turned out that competitively it also gave us a lot of room to grow before anyone understood the greatness of the basic idea.

2. A 3-Part Framework For Finding The Right Market

- Fiverr is my fourth company, and I think I was forming a thesis about companies in general that Fiverr fell right into. I was looking for an existing market with:

- A very sizable market, in our case it’s the freelancing market

- High degree of friction and inefficiency

- Where you can actually make the market more efficient with software

- It sounds simplistic. But what I just described is what Amazon did for the movement from commerce to e-commerce, what Airbnb did for hospitality, what Uber has done for transportation, and so forth.

- Taking large existing markets that have intrinsic inefficiencies and friction and solving or removing that through software. And that was exactly the thesis behind Fiverr.

- We saw the labor market in general, but specifically, the freelancing market, which is even to this day very old-fashioned. It’s based on word-of-mouth recommendations from friends. You meet the freelancer at Starbucks. It’s like a date, right? It takes a lot of time and then you need to start negotiating a deal, figuring out if you want to work together, contract and invoice, figure out how to exchange information, how do you pay in milestones, and so forth. And it’s all on an hourly basis.

- We took that idea of high friction + high inefficiency and we asked, can we solve this through software?

- The $5 was a gimmick to start with. And it also created a single price point so that we didn’t have to deal with multiple price points based on quality. We knew that over time we were going to extend that, but it was all about simplicity and removing that friction and inefficiency using software. That was it.

3. Fiverr’s Epiphany: Productizing Services

- What we’ve done is really productize services. That was the sophisticated issue, which was to create a skew-like system, a true e-commerce experience, where you have a true catalog of productized services.

- Now you come to Fiveer, you don’t hire people, you buy products. These products are being performed by people, but you know exactly who you work with because of our reputation system and the way you look at profiles. You know exactly what you’re going to get because it was predefined when you’re going to get it and exactly how much you’re going to pay. That level of transparency never existed before for businesses.

- That’s why it was such an epiphany for everyone. We thought freelancers were smart enough to know what to charge. So they can price. They name the price. We don’t.

- They’re sophisticated enough to know exactly what it’s worth for them to perform that task and that worked beautifully.

- With our go-to-market strategy, we started pretty much at the bottom of the market with microservices, for micro-businesses. And over time, we increased back to the more sophisticated types of services and businesses.

4. Reverse Your Storytelling In Order To Build The Best v1

- I do reverse storytelling in my mind. So I say, you know what: What is the Fiverr purpose many, many years from now? And from the very beginning, it was to become the everything store for digital services. Amazon for services.

- That’s how the book ends. Great. But how do you write page number one? And so essentially I was thinking about the components that we had to have in place for that to happen.

- And this meant: tens of thousands of different categories and verticals, and metadata, and data to create these sophisticated algorithms that would do sophisticated matching, and the type of support that we need, and the rest of the search technology, and all of that.

- And I said, great but these components appear in chapter number six. How do you write the book backward? You start removing those heroes and villains that appear in later chapters. You work back to page number one and try to remember what’s the purpose of page number one. It doesn’t matter which book it is, the sole purpose of page number one is for people to read it and get to page number two. That’s it.

- What would be the point of engagement that will buy you time to continue engaging your audience and retain them over time? So they’re willing to be patient to read your next chapters. That’s it. It’s a pretty general framework.

Let’s take that general approach and apply it to Fiverr:

- The first version of Fiverr was a full marketplace with about seven categories. Now we have well over 450 categories, and we add about 30 categories every quarter.

- You could offer anything within those seven categories, as long as it lists for $5. What we’ve done is we’ve removed the pricing friction that comes in later chapters and went with a single price, which made it very simple.

- $5 is the price of a frappuccino at Starbucks. Why is that important? Because if your coffee is not perfect, you’re not going to be devastated, you’re going to throw it, maybe get another one, maybe replace it, buy a different one. The risk of offering those services is very low, which meant that the screening process that we had to go through on the supply side was not very high, which simplified things. We didn’t have to put a screening marketplace integrity system in place from the beginning.

- We also knew that since it’s a true two-sided marketplace. There’s an issue of supply and demand. What comes first? How do you generate it? Where should you focus your energy?

- Now I’ll just get to the spoiler. It always, always, always starts from supply, with very few exceptions that are not worth discussing.

- A lot of the initial product was really to generate supply. It was really constructed around that notion. And we had a really nice and neat trick of how to do it.

5. Supply Generates Demand: The Fiverr Law of Business

- What we were NOT going to do: I swore to myself at the beginning of Fiverr that we were not going to pitch it through the media. We’re not going to go through these spikes of attention coming from the wrong people. We’re not going to spend marketing dollars on it because we really built this flywheel effect where we thought that this would be extremely sticky and viral because of its very unique approach.

- The first day we opened up the marketplace, it was empty. So we had to create a few services ourselves. I was offering a few things. My co-founder was offering a few things and we had, I don’t know, a page or two of listings.

- And then we wrote to five or six friends and we said, “Guys, please don’t post it to anyone, just look at it and tell us what you think.” And that was it.

- The first day we had like 200 uniques. We only told five people just from our friends which meant that they couldn’t help themselves. And from those people, we already had a few transactions, which was pretty amazing.

- We wanted to start creating the supply. What we did was really just going to all kinds of different services and sites and just randomly posting things about Fiverr. “Hey guys, you need to check it out.” We would go to a site and say, “Oh, you could be an amazing spokesperson. You should check it out.” And it took off like wildfire.

- One of the reasons was the way we constructed it. It was almost like a bait to post something you were willing to do for five bucks. I think that was a major part in starting the supply.

- Everything I’ve learned about business in the past 20 years boils down to this, at least for marketplaces, supply brings demand. Supply generates demand. It’s a law of business.

- So that created this flywheel effect where the actual supply was offering stuff and they were posting it saying, “Hey, I’m offering this on Fiverr.”

- And then people came in and said: “This is it. Oh my God, this is what I got for $5 on Fiverr.” Then this flywheel effect went super fast and it grew organically at the beginning.

6. Getting Your First Customers

- Acquiring customers differs across products because some products have intrinsic complexity built into them. Sometimes the only way to acquire customers is to go through a sales process and so forth.

- In the beginning, you don’t have to automate everything. It’s okay to do high touch at the beginning. Before you actually build to scale, you need to get to basic product-market fit.

- I always tell other founders that what we have in common is that we build products that we have a very clear understanding of or at least assumption of how customers are going to use them. And then customers come and they use them the way they want to use them.

- So that level of understanding in the beginning is more important than scale.

- One of the things that I did was spend the first 3 to 5 months at the beginning of the company doing customer support. That was my role, my main role, other than being the CEO of the company. I was doing most of the support at the beginning.

- The idea was to have an open dialogue with our community to understand what they like, what they dislike, what is missing, and I think that level of understanding really contributed to how we moved from version 0.9 to version 1 and 1.1 and so forth.

- I would say instead of obsessing about scale at the beginning, obsess about figuring out your value creation to your customers.

- The only way to do that is to interact with them. It’s to listen, to have conversations, and that will give you so many clues on how to scale.

- Well, then you can figure out what’s the best mechanism of growing.

- It’s fine spending marketing dollars, as long as your unit economics make sense. I’m not against that at all. But I think for us, the grassroots effect was extremely important for growth. More so, because we were starting at lower prices and the margin was such that we couldn’t afford to spend a large amount of money.

Talking to customers never stops:

- I’m still having these conversations every week. I’m not going to stop. And they’re random. They’re with members of our community. They could be businesses, they could be freelancers or agencies. They could be using one of our products or a number of them.

- The idea is really to understand the faces behind those accounts, understand their motivations, how they found out about us, what they use in our product, how well we’re communicating with them.

- The things that they don’t like are obviously more important than the things that they do. I’m having these conversations every week. It doesn’t stop being important.

7. How Fiverr Scaled Their Marketplace

- When you’re in the retail business, if you have an e-commerce platform, you have inventory on shelves and your sole purpose is to get rid of that inventory. But what is the inventory of a freelancer?

- It varies between people. Some people want to spend three hours a day doing this and some are willing to work 10 hours. Some are individuals and some are small agencies. How do you measure capacity? How do you balance that? How do you manage liquidity?

- Those tasks were really complex, but again, I think the approach was to build the catalog from a standpoint where we started very general with seven or eight categories. Eventually, most of them turned into verticals underneath those verticals.

- We created categories underneath those categories. We created subcategories. We created metadata. But to do this, you need to have scale because you’ll feel it’s too big in the beginning. As we were growing, we started focusing on this.

- For most marketplaces, with very few exceptions, if you’re both supply constrained and demand constrained, you’re in trouble. Most marketplaces are one side constrained.

- As an example, Uber is supply constrained. It needs as many drivers as it can get to have availability and to render service. The same is probably true for Airbnb. They need more hosts.

- Fiverr is the opposite. We’re demand constrained. The reality is that freelancers came to us organically. We never acquired supply. We’ve actually had plenty of it.

- In the early days, we had more than we could have provided work for. Over the years, it was great. We weren’t at capacity or close to capacity. And we knew that our freelancers, or at least most of our freelancers, could take more work and they wanted to.

- It was more of a focus on the demand side. On the supply side, it was really about creating the right capital structure.

- Right now, the level of depth that we have in our catalog is amazing. You can look for a voiceover artist:

- Voiceover is underneath music and audio and so forth. But the level of granularity is incredible. You can say if you need a female or a man voice. What language do you need? What type of accent do you need? What age range do you need? What should they specialize in? Is this a narration for a movie or is it radio advertising? It goes to that level of granularity.

- You can only get to that when you can look at millions of different services. This was structuring over time as we had more and more millions of services, we could go into that level of depth.

- That’s the productization of services. That’s the skew. The skew system that we built.

- We now have vertical managers. They’re responsible for ensuring that the liquidity of each category is in good shape and identifying which new categories or verticals we need to open.

- Now that we have more assets, we have industry stores. For example, we have a gaming store where we collect different services from about 20 different categories into one store that is dedicated for game developers.

8. Doing The Opposite Of What You’re Told For A Go-To-Market Strategy

- The go-to-market strategy was that we want to occupy the entire market, but we need to start somewhere. And it was either starting at the top, middle or bottom of the market.

- When I look at business history, there are very few examples of companies that have been able to go down market without compromising their premium business. So if you start from the premium side of the business, going down to small businesses is really hard. It’s hard because it’s not your DNA. It’s hard because it might alienate your premium market.

- What we’ve done is the opposite of that. We said we’re going to start at the bottom of the market with microservices for micro-businesses.

- The vast majority of them are businesses, but when you’re a solopreneur, you act as a consumer more than as a business.

- We started there and over time, we went to larger types of businesses with more sophisticated products, but that also allowed us to do market education as we were going up market.

- That was buying us time because we were very successful at the microservices. That’s fueled our efforts in going up market and gaining the market’s trust. The other way around is going from the upper market down. And that’s really hard.

- I’m not the expert, but when looking at the business of Uber, I think that Uber went down market. It started with black cars and went into the equivalent of a taxi. I think that was very much at the expense of the black car business. That’s exactly what I’m saying. When you go down market, there is a price to be paid on that. We thought that the strategy of going up market made more sense. It definitely worked.

- Being able to take your brand and serve enterprises is always going to be a challenge. You need to make sure that there’s still room on your platform for the people that are providing or looking for these niche services. But at the same time, you’ve added layers of trust and layers of seriousness to the brand that are now enabling enterprises to use it. That’s not a trivial challenge.

- It’s from a perception standpoint. It is complex because you’re basically re-inventing your image in the eyes of your potential customers. You qualify yourself to cater to larger types of customers, which is not obvious when you focus on a specific segment. But I think that that is one of the beauties of creating a truly horizontal marketplace.

- Don’t forget that every business owner or every member of a business is also an individual, right? They’re also a private person with private needs like a true customer, true consumer.

- I think the misconception was that a lot of people were drawn to the more colorful types of services that were offered on Fiverr, not knowing that they were a very small minority of our business.

- They generated noise, but they didn’t generate as much business. But the noise that they were generating drew a lot of attention to the business side of what we’re doing, which was always the majority of our business.

- So from that perspective, moving up market was not that hard, but changing the perception of the brand, making it more accessible for larger types of customers to consider was something that just took time and took storytelling.

- We had to prove that we were able to cater to those customers. It was recreating a trust system. It was bringing more high-quality supply, creating more professional categories, and so forth.

9. “If You Care About Your Customers, Don’t Call Them Users.”

- When you think about both small businesses and freelancers, if they have something in common, it’s that they’re lonely, they’re alone. If you’re a freelancer, you spend a lot of your time in your home, in your pajamas, in coffee shops. And you can be alone too in a lot of small businesses. So what I said at the beginning is I don’t want anyone to be a username on Fiverr. I want them to be community members. What would that take? How do you do that?

- The first thing is to start a forum. Start from the basics. Create the place where you allow, you encourage, you empower people to have a conversation. And the reality was that a lot of that conversation wasn’t with us. We connected them with each other.

- That was just the beginning. After that, we said let’s go to whatever city in the world, London, New York, San Francisco, and so forth, and close the bar and just invite local community members to have a drink with us.

- We did this five, six, seven, eight times. And it started gaining traction. All of a sudden, we got requests for so many different places in the world saying, “Hey, can we do this?”

- The actual answer is no, we can’t. We’re a startup and we can’t be everywhere. So the community reached out to us and asked, “Can we do it ourselves?” We said, “Heck sure.”

- So we put together this operating system that allowed them to find venues and invite each other and have those meetings. And very soon we had hundreds of them every year.

- Before COVID-19, we had about one event every day somewhere in the world. They were all self-organized. We thought that at the beginning this was just going to be freelancers. But the reality is that both freelancers and small businesses come together, they talk about stuff. They talk about entrepreneurship. They talk about starting up. They talk about growth. They talk about how to develop.

- This is where the exchange happens. It’s one part. The other part is just caring. If you care to have a community, you will have a community. If you care about your customers, if you don’t call them users, if you call them what they are, either community members or customers or freelancers or whatever, but just don’t call them users.

- If you understand that they are your constituents, these are the people that you work for. It’s not just your shareholders, it’s your community that relies on you every day. It’s their home page. It’s where they spend the majority of their days. You can’t break it. It gives you a sense of responsibility.

- If you go to our editorial team here, they know so many people by name, they know their stories. They know who they are and we have millions on the platform. Even though that is the case, we have so many personal anecdotes and people that share their stories with us. That’s extremely powerful.

10. Why Fiverr Made Everything $5

- For pricing, our initial idea was to go with five. We thought that this was a price where people would not dwell on it for too long. We felt that five was a safe number.

- We did have a debate on potentially going with other prices, but 5 is what we ended up with. I think, in hindsight, it was smart.

- It’s hard to say what would have happened with different prices. But I think that this was a sweet spot in terms of pricing. And it definitely worked out for us at the beginning.

- Now we can test this stuff in five minutes, but when you have zero traffic and zero traction and nothing, it’s like testing stuff in a lab. It doesn’t really give you the right signals that would help you make any decision.

- One of the complex things that we had was breaking the $5 internally. How do we actually scale it when you have a marketplace that is only $5? How do you scale beyond that? If you have done relatively little vetting of the supply, how do you allow yourself to scale without risking quality and satisfaction?

- This was the most sophisticated portion of it. Figuring out how to do this was one of the smartest things that we’ve done. Again, in hindsight.

- We started to notice that freelancers were basically agreeing with customers to charge them four times five or ten times five. Seeing those signals where the market itself found ways to overcome the price limitation was definitely one of the bigger motivations for expanding our pricing.

Price Needs to Coincide With Quality:

- The one thing that matters is quality, right? If you want to increase your prices, it needs to coincide with quality. It needs to go hand in hand. And that was our focus.

- The focus was how to ensure that once we allow freelancers to increase their prices, quality would go hand in hand with that. And that was the core of the product creation to allow that to change.

- Obviously, as you know, as the company grows, there are other functions that you didn’t need to have before in customer care, fraud, marketplace integrity, vertical management, and so forth.

- Our community was ready for it. Luckily, that transition was very smooth for us.

- But as you do that, you need to change the way you measure your business. You’ve moved from a single price point to multiple price points. You need to start analyzing cohort behavior in a different manner. But this was gradual.

- For us, it was an evolution of the business. It wasn’t an overnight change. We had time to get ready for it.

11. Keeping “Startup Speed” Even As A Public Company

- Growth is about your mentality. Moving fast is one of those things that is important for the organization, it’s something your team needs to understand and put into practice.

- Beyond that, it’s giving the infrastructure to move fast and allow your team to develop things quickly. They need to be able to test, to create a hypothesis, to create your A/B testing system, to create your BI understanding. Internalize and integrate your data learnings into your product.

- All of these are essential ingredients to be able to move fast because just moving fast for the sake of moving fast doesn’t give you a lot if you don’t learn anything from it.

- I think that the mentality of allowing teams to move fast, but also fail fast and move on, not dwell over it, not spend too much time on it, but also understand how to run tests is critical.

- It’s not enough to have an idea for a test. You need to deeply understand it. Sometimes we ran tests that on a local level performed well, but on a global level performed poorly. In those cases, you could actually achieve better results in click-through conversion or whatever, but their implication on cross-category purchases or on retention might be terrible.

- Sometimes when you’re too myopic in looking at specific stuff that you’re testing, you’re missing the larger picture. That’s very true for marketplaces because marketplaces are extremely complex creatures.

- By putting this infrastructure and methodology in place, it allows us to move fast and it’s also how you structure your team. Do you work in squads? Do you work in task forces? Guilds? Whatever your format is, how do you empower those teams? How do you know which areas to focus on?

- There’s not one answer for it. It’s having a moving fast mentality and not changing that when the company grows.

- Understanding that the company needs to continue making big bets, knowing that some of those bets are going to fail, but if you can have one or two big bets every year that gives you dividends, they’ll outperform all of your failures combined.

- You need to have that mentality of integrating those learnings very fast. We developed our own methodology of how we retrospect stuff, how we learn from everything we do, how we share that knowledge across the organization to make sure that we don’t make the same mistakes over and over again.

There are two important principles:

- One is you need people to know that nobody here knows where the next big idea is going to come from. It might be them.

- You need to create this environment where you empower people to speak up and share their ideas and understand how the machine actually works.

- When I greet new team members, one of the things that I tell them is there’s no one in Fiverr who’s a black box. You guys don’t just have inputs and outputs. You need to understand the larger picture. You need to understand how this machine actually works. It doesn’t matter what your role in the company is, because that’s the only way you can be impactful.

- I always give two examples. One is the example of Amazon Prime. You probably know the story of Amazon Prime, which now I think is a double-digit percentage of Amazon’s, revenue. Prime was invented by an individual contributor in the company. One of 1.2 million people.

- This guy was not even a team manager or a top executive. He came up with this idea that turned into this incredible product. And the same goes for Fiverr.

- We did a hackathon a few years ago. We called people to pitch ideas. We said we’re going to pick 10 and two or three out of the 10 we picked were pitched by the receptionist. That is the level of understanding within the company of how the machine works.

- I think this is the first thing that is very important. The other thing is don’t fire people when they make mistakes.

- As long as there are learnings, as long as people are not just crazy by making the same mistake over and over again, which is a bad sign if they do. If they make a mistake in good faith because they wanted to do something good, you need to empower them to take the learnings out of it, that will make them better executors.

- Before COVID-19, we actually had this event every one or two quarters where we gathered the entire production team and we would bring champagne to celebrate failures. People would share their stories of massive failures with a lot of pride. Obviously, including what are the key takeaways from it. This was really powerful.

12. The Future of Work Is Now

I think COVID is a milestone in a movement that started at the beginning of the 2010s. Here’s my view of what’s going on in the past decade and in this decade.

- The 2010s ended up being the decade in which freelancing became mainstream. What I mean by that is freelancing used to be something you would do in between jobs, but this is no longer the case. People choose freelancing as a career path. They choose it as a lifestyle. It’s no longer something you’re forced to do.

- The cohort that has made this change happen are millennials. They joined the workforce in 2010 and created this massive change. From less than 30% of the American workforce, freelancers are more than 40% of the American workforce right now.

- The 2010s were all about changing how people viewed work. Let’s think about what this does to the 2020s. My view of it is because so often people don’t want to be full-time hires, it means that businesses need to figure out how to integrate this flexible talent into their workflows. This is to me what this decade is going to be all about.

- This is where Fiverr is going. Now, we’re creating this operating system that allows that to happen. I think that COVID-19 has created an acceleration point but it was happening before that.

- It made the case for what we were preaching for 10 years, which is, the average time that it takes to find and hire a freelancer anywhere is about 30 days. It’s a long process. The time that it takes a customer to visit Fiverr.com, take their credit card out and place an order takes 15 minutes. That’s the simplicity. It’s the trade-off of 30 days to 15 minutes.

- Once you go through that process, you’re not going to go back. I think that because of the global lockdown back in March, offline didn’t exist. Everyone was moving online.

- I think that we were just in a perfect situation to capture the supply and the demand side, but this was just an acceleration point. I think that’s created an awareness on both sides of the marketplace that it is indeed friction-free and extremely efficient. It just works well.

- I think that we’re going to see a lot of development around what people call the future of work, which I think is here. It’s not really the future. We’re obsessed with trying to figure out how to help shape that. That’s my view on what we’re going to see in the current decade.

You can listen to the podcast conversation here.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.