Behind every iconic company is a radical, risk-laden idea. But as the startup ecosystem has grown, we’ve seen a decreasing appetite for risk & an increased emphasis on predictability and familiarity. Yet if you carefully study the most successful technology companies of our time, you’ll find something curious – not only are they born from risk, but they’ve survived and thrived because they knew how to evaluate risk itself.

To build iconic companies, Founders must take more risks, not less. But they also need to understand how to classify and assess the types of risk they will encounter. Trulia would have never become one of the most prolific PropTech companies had I not quickly learned how to do this.

I fear the pendulum has swung too far in the wrong direction to produce the kind of companies that technology promises – the kind of companies Founders dream of building. So today, I am sharing a framework for all Founders to evaluate startup risk.

2 Types of (Necessary) Startup Risk

To take risks strategically we must first understand them. We have to be sure that the biggest risks we are taking are necessary, so we can have the conviction to take them. We also have to be able to identify and avoid unnecessary risks so that, if our companies fail, it won’t be because we took avoidable risks.

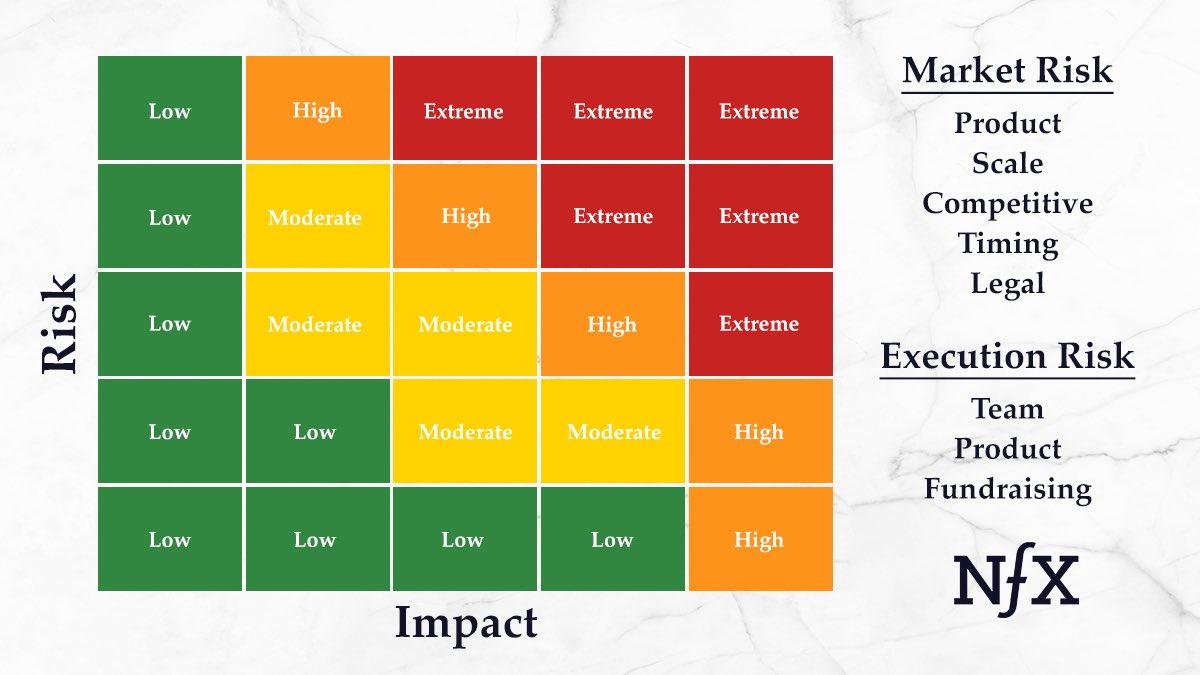

As we’ve written about recently, two types of risk Founders trade off between are market risk and execution risk. Market risk is the risk that people may not want what you’re building. Execution risk is the risk that you might not be able to execute your idea better than the competition. Or as one memorable aphorism puts it, “vision without execution is just hallucination”.

When we introduced this framework, we pointed out that startup ideas with higher market risk are usually the best option for first-time entrepreneurs looking to avoid incumbents and competitors. By contrast, experienced entrepreneurs will often choose to take on more execution risk because they have more confidence in their ability to execute.

But to help Founders truly calculate how they should assess the risks involved with their startups, let’s take a deeper dive into what these two types of risk mean and where they really come from.

Sources of Market Risk

Market risks are outside of your direct control as a startup. But if you understand the sources of market risk, you can make better decisions upfront as a Founder on whether to start a startup in a given market category.

1. Product Risk — Do people want your product?

Founders often decide to start companies with a founding insight. This is usually an observation or realization of a commonly experienced problem that has become solvable through technological innovation.

For example, when I founded Trulia, my founding insight was that home buyers looking to make the biggest financial transaction of their lives would increasingly want to start their search online — and that there didn’t yet exist a good online resource for this purpose.

Once you have a founding insight, you can iterate on a product until you get to product-market fit and deliver a solution on the founding insight.

Not achieving product-market fit is possibly the biggest risk of all for first-time Founders starting companies with high market risk. In other words, your product risk comes down to how certain you can be about the accuracy of your founding insight. To properly assess it, ask yourself what evidence you have even from an early stage:

- Is your founding insight addressing a clear pain point?

- How big of a problem are you solving?

- Do you have evidence that people are willing to pay money for a solution?

The more data and information you have to corroborate that there’s a real need for your product — and that you will produce real value for your users — the lower this risk.

Early on as a Founder, it’s best to take whatever steps you can to minimize market risk before you start a company and raise capital. The longer it takes you to get to product-market fit, the harder everything else with your startup will become.

The best evidence of low market risk is obviously the existence of thriving businesses that already exist and provide a similar product. But, as we’ll discuss further below, the less market risk you can perceive because of the presence of competition, the more execution risk you tend to take on.

The best market-risk companies have strong evidence that there will be demand for their product and low to non-existent competition.

2. Scale Risk — Is there a big enough market?

The size of the market for your product is (mostly) outside of your control, but one of the biggest avoidable risks I see Founders take is starting companies where the potential market is too small for the economics of a venture-backed company.

There are many good, profitable businesses that can be built in smaller market categories, but these are not usually VC-backable. The real problem is that a small addressable market means that any company, no matter how well-run, cannot achieve the necessary scale to profitably build a breakthrough product with transformative impact and venture scale returns.

Startups that raise VC money must have the ability to (profitably) scale in order for them to be successful. It’s not always obvious what the size of the market for a product is or will be, but sometimes even a cursory glance at the market research will make it evident that the TAM is too small to ever support a potential billion-dollar company.

The exception to this is if you are building a new market like Lyft was doing in the early days. They essentially invented the ride-sharing market category, and so existing data around the size of the taxi industry was not a good indicator of market size. Lyft isn’t just going after the “taxi” problem. They are going after something much bigger — the problem of transportation.

While the size of a potential market for your startup isn’t identical to the size of the problem you’re tackling, there’s usually some correlation. If you’re looking to create a transformative company, it’s important to tackle a big problem.

Not all companies that end up having a huge market size know it at first. Companies like Slack and Instagram stumbled upon huge markets after seeing early traction with a particular feature of their products and looking to rapidly scale in that direction. The strategy is to double down on a market and scale up your ambition once you see early evidence of traction, and this can be one smart way to attenuate market risk.

3. Competitive Risk — What is the competitive landscape?

Another market-related risk to consider is the risk of competition. Big ideas with high market risk usually have limited direct competition, but sizable indirect competition from adjacent market categories.

As we’ve written about in the past, defensibility is the biggest factor in how valuable a company eventually becomes, and network effects are the best form of defensibility. 70% of the market capitalization in tech over the last 20+ years comes from companies with strong enough network effects to heavily mitigate competitive risk.

So as a Founder, it’s important to ask what the competitive landscape looks like. Are there already entrenched incumbents with strong defensibility within or adjacent to your market category? Are there a lot of other competing startups?

While it is possible to compete and win in hypercompetitive markets, as I’ve written about before, facing heavy competition creates significant risk.

Whether or not there’s already a lot of existing competition in any given market category, you can bet that eventually there will be. That’s why one of the most important risks to limit early on is the risk of later entrants eating into your market share by developing a sound defensibility strategy and ideally, building network effects into your product.

4. Timing Risk — Is this the right time?

The last significant risk outside of your direct control is timing.

In my essay, Why Startup Timing Is Everything, I break down the three preconditions that you should look for in a market to know if the timing is right to start a startup: economic impetus, enabling technologies, and cultural acceptance.

When a market reaches a critical mass of these three preconditions, there is an inflection point in the available market size so large that it can determine the success or failure of a given company.

Companies founded before this inflection point, despite having similar or identical products to later success companies in the same market, often fail for this reason alone (poor timing).

By contrast, companies that are too late to a market frequently find a lot of difficulty gaining traction because of entrenched competition. They often fail also.

Understand the current state of the market you’re getting into. The closer you can time your startup to the critical mass inflection point, the lower your risk.

5. Legal Risk — What is the regulatory environment?

Most iconic companies in tech end up having to navigate the obstacle of regulation. When they first got going, Uber had to deal with transport regulations, Airbnb had to deal with housing authority, and Youtube was dealing with copyright issues.

Usually, the regulatory environment surrounding an industry lags behind fast-moving technological innovation seen in startups. But it’s important to know that, just as with all the examples above, if you’re providing sufficient value to the key members of the ecosystem, you’re not breaking laws, and you are able to thoughtfully navigate the marketplace, then it is often a risk worth taking.

The fact that you might face regulatory hurdles doesn’t mean it’s a bad business. Fully self-driving cars are currently illegal, but most of the major transportation businesses in the world are developing autonomous vehicles.

If you face regulatory risk, you just need to be thoughtful about how you approach it. YouTube, for example, abided by takedown notices to protect copyright early on, but they continued to offer their core service which provided a lot of value to both content producers and consumers, and ultimately led to a $1.6 B acquisition by Google.

The continued presence of unauthorized material on YouTube after the Google acquisition led to a number of lawsuits that Google was able to bankroll, which brings up another point. If you’re operating in an environment of high regulatory uncertainty, you need to have the patience and the bankroll to sustain heightened legal and regulatory costs.

The lessons is that if your business is providing value and the legal environment was designed for an outdated technological era, there’s sometimes a path to building a meaningful business, and you shouldn’t be intimidated by regulatory uncertainty.

However, this varies on a case-by-case basis and it’s really a question of magnitude, and you should certainly be careful about overreaching or breaking any laws. It’s also important to be cognizant of societal impact. Ultimately, a lot of the decision around regulatory risk is around the downstream implications of pushing the envelope — a failed medical diagnosis or an erroneous self-driving car is a lot more damaging than disrupting legacy media platforms with online comedy videos.

Sources of Execution Risk

Execution risks are more in your direct control than market risks, so taking on execution risk is betting on your own ability to execute in 3 basic areas: recruiting a world-class team, having the technical capacity to build the product itself, and fundraising aptitude.

1. Team Risk — Can you recruit world-class talent?

As a Founder, you’re likely to have a lot of confidence in the quality and abilities of your own founding team, but early hires can be just as important for startups.

To assess team risk, take a look at your existing professional network and those of your co-Founders. Do you have access to networks in centers of excellence, like a top-performing company or university? Are you geographically located in an ecosystem with an abundance of available talent? As you scale, will you be able to attract top candidates for your VP of Sales or Finance?

One of the big reasons why second-time Founders choose to adopt execution risk is because they can limit that risk with well-developed professional networks which give them more confidence that they can recruit the top people to help them make their vision a reality in the face of technical or competitive obstacles.

Assess which professional network clusters you have access to for early hires before you start a startup, and, if necessary, do the work of developing ties with potential future sources of talent.

In building a strong team, it’s also important to realize that having just raw talent won’t be enough. Equally crucial is the need to have the right mix of complementary team DNA so that the team is able to work together in an ambiguous, pressure-filled startup environment and build a great culture and organization.

2. Product Execution Risk — Can you build it?

Can you actually build the product you want to build?

One of the reasons early-stage investors often look for technical co-Founders is to mitigate this risk.

The more control you as a Founder have over your ability to execute on the product, the less your execution risk. Relying on early hires to build out your concept carries costs with it, because no matter what, you will probably always be the most motivated person at the company to make the business work.

The more you or your co-Founder can guide and influence the execution of the product itself, the lower your product risk.

3. Fundraising Risk — Can you fundraise?

Fundraising is a completely different skillset from leading an organization, technical execution, and business strategy. But for a venture-backed startup, it is equally crucial in the success of your company.

While fundraising is something you can learn and develop (see our essays on 16 Non-Obvious Fundraising Lessons on Pitching, The Fundraising Checklist, and The Ladder of Proof), it’s often best if at least one Founder is comfortable with sales and pitching because it’s a core area of competency required for a Founder to succeed.

How Investors View Risk

In addition to being able to calculate and manage risk as a Founder, you should also understand how investors see risk so that you can be more successful in your fundraising process.

From an investor’s perspective, not all risks are created equal. Investors tend to be biased toward companies with high market risk, but low execution risk.

Why? Because the early-stage VC model is built on high variance investments. Most Funds are made by taking big risks for the chance of getting a huge outcome.

The math looks something like this: if I invest in a market risk company, it might have a 10% chance of having a huge $1B+ outcome, vs. investing in an execution risk company with a 30% chance of a 200M outcome.

Companies with massive defensibilities, i.e. network effects, have the most potential to become huge, iconic companies. But these companies usually have a lot of market risk and are doing something non-obvious that no one else is doing.

Most companies with low market risk are in industries that are very competitive. A lot of people go after it because it’s somewhat obvious. For that reason, it’s tougher to create breakthrough companies with large market share and high defensibility (and therefore high margins).

VCs, however, will sometimes invest in startups going into proven markets with lots of competition if the execution risk is relatively low — either if the startup has an exceptional team or product and strong Founder-Market Fit, or if there is an opportunity for meaningful technology-driven disruption in the market, e.g. a platform shift.

Another thing to be aware of is that investors are also less prone to taking team risk, but more prone to taking technical risk. If you have an amazing team but it’s unclear whether what you’re proposing can actually be done, investors might still back you, as we see with companies like Magic Leap.

This is because investors see team risk as binary — either it’s a high-quality team with the capacity to attract other top performers from centers of excellence or its not. Technical risk is not seen the same way, as in tech there’s a strong belief that given enough time and money you will always figure out a technical solution.

As a result, I encourage Founders to think big and take more technical risk. Investors tend to believe that everything is possible given enough time, money, and the right people. You should have the same outlook. Personally, as a VC, I would love to see more companies taking big, bold technical risks.

Living in the future

One method to come up with a big, bold, radical idea is to implant yourself in the future and think about how people’s lives and needs might be different. Anticipating the needs of tomorrow is one of the best ways to come up with startup ideas today.

One underrated way to do this is by turning to science fiction. Many of our iconic technologies today were predicted or portrayed by imaginative science fiction of previous generations. Think of the self-driving cars in Isaac Azimov’s “I, Robot”, or voice-activated computers depicted in Star Trek long before they had become a household commodity with Alexa.

Another way to do it is by extrapolating big trends in underlying economics (such as changes in costs of computation, storage, genomic sequencing, photovoltaic cells, etc.), penetration of enabling technologies (like increasing smartphone adoption, enterprise cloud computing), or cultural change to anticipate new sources of demand or new enabling technologies.

In addition, given that many of the most interesting trends are compounding or exponential in nature, you can see orders of magnitude difference in just a few years. We tend to think intuitively in a linear fashion, so superlinear trends can catch us by surprise and can rapidly create new market opportunities.

The Varian Rule can also be used to extrapolate future trends in consumer business. Named for Google’s chief economist Hal Varian, this rule holds that “a simple way to forecast the future is to look at what rich people have today; middle-income people will have something equivalent in 10 years, and poor people will have it in an additional decade”.

In other words, The luxury goods of today are often the necessities of tomorrow. Some examples of services which were, until recently, inaccessible to anyone except the very wealthy:

- Personal shopping (Instacart)

- Personal driver (Uber/Lyft)

- Personal stylist (StitchFix).

Whatever method you use to come up with your founding insight, creating an iconic company comes down to tackling a big, important problem with a radical idea. Understand and be strategic about the risks you take on, but don’t shy away from taking them. Risk is, at the end of the day, innate to being an entrepreneur and the lifeblood of the startup ecosystem. Founders, investors, and everyone else in the ecosystem should recognize this and embrace risk-taking as part of our identity.

Why Risk Is Critical

One of the things that drew me to Silicon Valley over fifteen years ago from the UK was the spirit of innovation and risk-taking. It’s that same spirit that continues to draw innovators and technical talent to the startup ecosystem from all over the globe.

The tech and startup ecosystem has long represented an oasis from the drudgery of traditional industry. With its culture of bucking the norms, trying the unproven, and pursuing innovation for its own sake, it was a magnet for people with radical ideas who were crazy enough to pursue them.

Today, the costs of starting a startup are lower than ever, which is an amazing thing. But a growing backdrop of fear and caution means the startup system is more filled with unambitious and unexciting ideas. While there has been a (healthy) education about the importance of taking calculated risks with business models, too often this has been accompanied by an unwillingness to think big enough and to tackle truly important problems.

I believe the startup ecosystem has the continued potential to deliver on our highest aspirations for the future. But we can’t lose our willingness to take big risks. Today I want to look at how risk can be strategically managed by avoiding the unnecessary and embracing necessary risk. Hopefully, this will empower Founders to take more of it.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.