Whenever I talk with early-stage Founders they are always worried about growth. It’s an easy mental trap to fall into — up and to the right growth is a windfall for startups because it generally means more users, more revenue, more success.

But many Founders fail to realize that the reason they aren’t growing is because they’ve missed a mission-critical step.

It’s well known that product-market fit is the absolute prerequisite to sustainable growth. It’s pointless to try to grow without a great offering that you’ve already proven that people want, need, and love.

But less known is an even earlier and equally mission-critical step. One that can save you months and millions. Before you can find product-market fit, you need to first define your product’s promise. I call this finding your product-promise-market fit. And it doesn’t require a single line of code.

There are 3 reasons many Founders skip the step of finding product-promise:

- First, Founders are essentially product people at heart. Whether we are creating services, marketplaces, entertainment, software, or something else, Founders are “builders” who have a vision of bringing something new to the world. We are eager to see and feel the impact of what we make, so we often race ahead. Building feels like a critical step in validating. That’s of course true — but it’s not the first step.

- It is widely accepted that the primary goal of any new company is product-market fit. Much has been written about product-market fit that you can find in great books like Eric Ries’s Lean Startup and Steve Blank’s excellent writing. As a result, most startups think that the only valid process is: build a lean MVP, iterate until you nail product-market fit, and grow. Again, this is not untrue — it’s just not the starting point.

- The last reason is that validating your product promise wasn’t easy to do (and sometimes not possible) even just a few years ago. It’s the emergence of better targeted and more segmented advertising platforms like Facebook that make this so easy to do today.

What the smartest startups know is that we have to first earn the right to build. Before we start building, we have to test our ideas against the market.

Not only will this unlock speed for your startup and save you time and money (the two non-renewable resources that early-stage startups most need to protect and maximize) — it will also accelerate and strengthen your discovery of true product-market fit.

Why product-market fit is critical

The #1 reason startups fail is that they run out of money before achieving product-market fit. Simple as that. Once you have product-market fit, funding is usually dramatically easier.

There are many different definitions of product-market fit, but in essence, they all revolve around three basic components: identified customers who want your solution, in a market large enough to justify the business.

Simply put, product-market fit is that magical moment when you become a must-have in your customers’ minds. This happens when you solve a real problem for them, or help them do something 10x better, or you allow them to do something they couldn’t do before.

A simple test for product-market fit

One test for product-market fit: look at all the products you are using in your everyday life. Now ask yourself of each product: “If someone took this product away from me, would I be upset? Would it make my life harder in some way?”

The strongest product-market fit comes when users find they can’t live without a product.

Imagine what would happen if Google Maps and Waze were suddenly deleted from your phone forever — right when you were trying to get somewhere. Similarly, how would you feel if your new iPhone was discontinued? Or if Uber/Lyft were no longer available. You would probably feel that pain acutely.

If you love something, you use it routinely, and it makes your life easier or better — and if you can’t do without it — then that product has strong product-market fit.

When Slack was in its early stages, many companies tried to stop their employees from using it, saying it was against corporate security guidelines. Employees were so unwilling to do without the product, however, that companies were forced to find a way to accommodate their demands.

Real value is transformative

Products with product-market fit will bring real value to users. Value can come in many forms: money, time-saving, enjoyment, peace of mind, etc. But the thing you’re offering has to produce true value for users — it has to materially affect and transform their habits and lives — in order for you to have a business worth growing.

There’s little point to aggressively marketing a product that brings no value to its users. They may initially come to check things out but they’ll eventually leave. It’s like pouring water into a leaky bucket: even if it seems full for a second, it is very quickly empty again. That’s why product-market fit, delivering real value to your users, is so critical. It gives you a solid foundation from which to grow.

When my partner Pete Flint talked with Andy Johns (formerly lead of the growth teams at Facebook) on our NFX podcast, Andy revealed something that most Founders today may not realize: that Silicon Valley’s obsession with “growth hacking” was misguided. That’s because it was rooted in an extreme anomaly — companies like Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn — which had already achieved product-market fit. That was their secret enabling them to scale via internal growth teams.

But first, find your product promise

But is product-market fit truly the cornerstone of product development? It’s clearly a critical step, but I believe there is an even earlier step. First, you need to find your “product promise” and your “product-promise-market fit.”

To understand this, we need to break classic product-market fit into two distinct stages:

Stage 1: Finding a product idea that users want — a concept that sticks.

Stage 2: Executing on the product — actually building it well.

These are very different challenges. But the traditional product-market fit process bundles both of these stages together, as discovery is done through exposing the users to the actual product you build (or at least, something lean that mimics it).

But why spend time and money to build the product if you can first check whether your product promise — the theoretical approval that users give to the idea of a product —resonates with your customers?

It used to be that there was no other way. Before the days of modern online marketing, the theoretical way to try to check your product promise involved focus groups. But, as many brands found over time, users didn’t always behave in these groups the way they eventually consumed a product. Plus, the way you asked the questions often impacted the outcome of the focus group.

So, for lack of choice, building the product early (or at least its most important core, the MVP) became the norm, even in the agile startup world. This is no longer true today, especially now that you can test your product promise any number of ways before you even start building your product.

The product promise is in fact the first step of finding your product-market fit — and testing its validity should be done before spending any effort on building the product. This is especially true because, when separated out, Stage 1 above takes probably less than 5% of the time and cost of the entire product-market fit discovery process, but gives more than 50% of the validation required.

So, how to measure your product promise?

What you are actually testing is if customers respond well, and in a measurable manner, to your product concept. You are using language instead of code as your building blocks. You are telling your product’s story the way you would market it if it had already been built. For this reason, the description needs to be precise and true. You will only be tricking yourself if you verify an imprecise product promise. You can’t over-promise either. There’s zero point in getting good feedback for features you might be able to deliver in five years. What you need to do is ensure that the basic, core MVP that you are about to build is going to be well received.

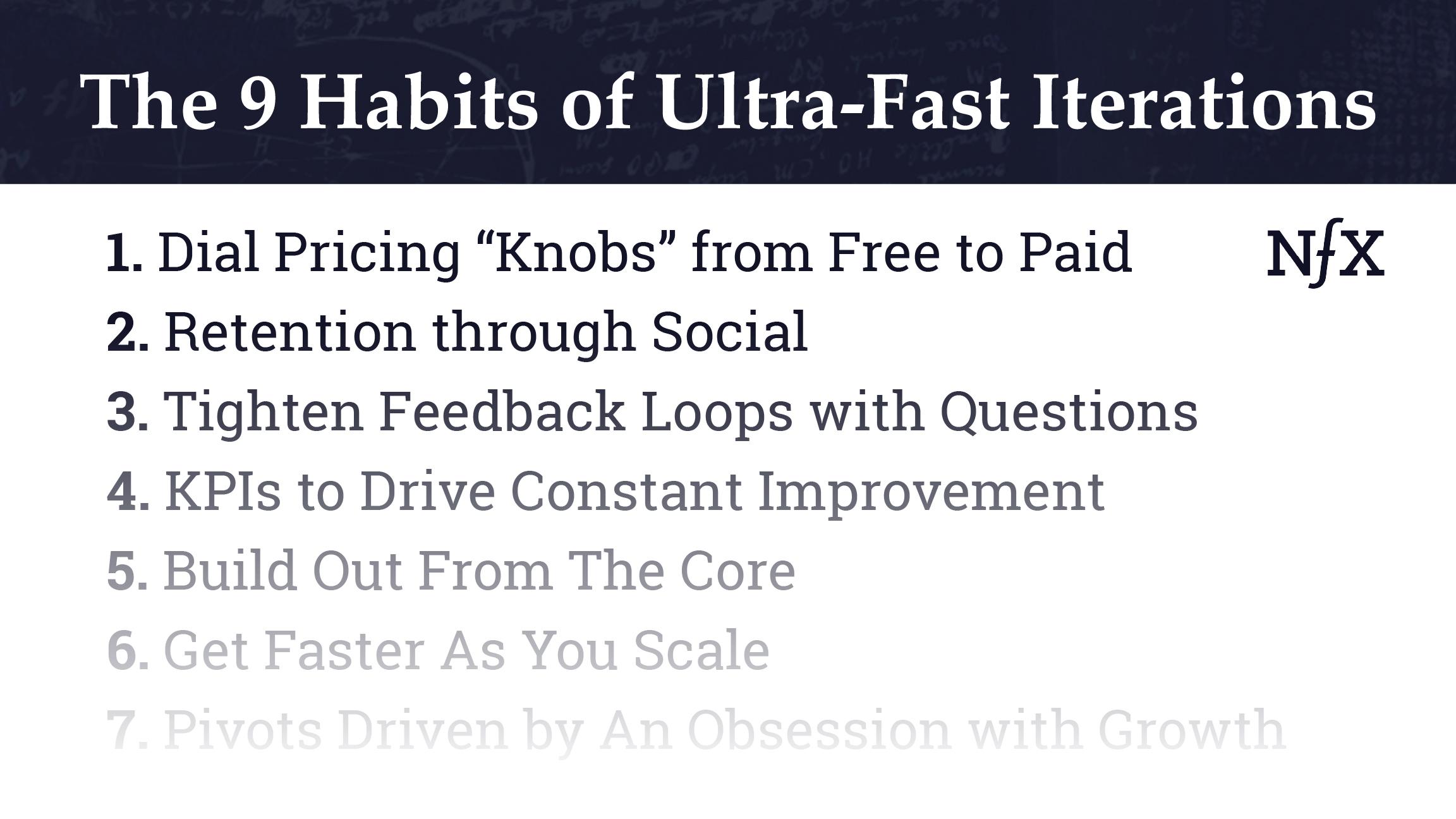

Once you have a crystallized product promise down on paper — in terms of clearly defining the language, positioning, pricing, benefits, and value to your users — then the rest of the process of measuring for promise-market fit is straightforward:

- Create a bunch of ad campaigns for your product promise, to test different stories and theories.

- Set up multiple landing pages and calls to action.

- Define your audience on your chosen platform.

- Start marketing.

- Analyze campaign success and optimize until you get to a validated product promise.

If this sounds familiar, it’s okay. This is the exact product-market fit building and optimizing process — only with words before you have code.

You are marketing your product promise instead of a built product. You are sending your potential users to a landing page where you try to get them to respond to your call to action and convert into a “user.” Do this over and over again with different setups. Test like crazy, measuring everything, every step of the way. You need to think like a mad scientist experimenting with your language, art, CTA, pricing, ad channels, and audiences. But remember, your goal is to do this without writing a single line of code.

People often ask whether testing a product promise in this way can annoy or frustrate users. Wouldn’t they be upset that the product is not live? That you “tricked” them into clicking what ended up a waste of time?

The answer is no. You’re not lying to anyone.

You can tell them at the end of the flow that the product is coming soon. You can give them a large discount or status or reward for being early, for being first, for giving you feedback. Never underestimate human interest in that which is new.

If you are really worried, you can launch the test campaign under a different brand name, which you can change once you’re ready to go to market with a built product. At the very worst, you will be slightly upsetting a few hundred or a thousand users. That’s not a reason to build the wrong MVP without testing its product promise first.

Numbers don’t lie

Throughout this testing process, the need for benchmarking data is critical. Without data, you won’t be able to analyze your different campaign results to find out whether your product promise is positively received, or whether it’s had only a lukewarm response. For example, if you don’t know what clickthrough rate to expect for your specific audience, you will not be able to reach meaningful conclusions. Is a 1% clickthrough on an ad for small business owners in New York great or horrible? And if only 2% then give you their email, what should you make of it?

This data, which used to be the most secret asset of each company, is now a lot easier to come by. There is so much open-sourced and available marketing information from so many experts that you can easily learn how to benchmark your own data.

The two key metrics you must monitor as you test your product promise on a specific market are your ads CTR and the conversion of the landing page’s CTA. These will help you determine (compared to the benchmarks) how users have responded to your product promise. Later, when you’re measuring actual product-market fit, retention analysis — especially a cohort analysis — is usually the best KPI to determine if you’ve achieved it.

One critical thing to remember is that numbers don’t lie. Yes, you will need to run multiple tests at a time, because numbers can be depressed due to poor creative (which is why you should try a few different design options), or a badly set up campaign (which is why you set up more than one campaign), or your landing page might have the wrong CTA and therefore your conversions are low (so you should set up a few landing pages). But in general, looking at your data from the different tests, you will see that the numbers are always directionally correct. If the landing pages you set up have great conversions, then you are off to a great start and you can start building your MVP. If the numbers are bad, you should continue iterating on your product promise until you get it right.

As with most things, the middle ground is the hardest. If your numbers are just okay, it is easy to trick yourself into believing that’s good enough — thinking that once someone sees your “real” product, they will fall in love with it. This is never the case. If your early product-promise-market fit data is coming in at a solid “okay” then I strongly recommend iterating until you find a great product promise with white-hot conversion rates.

Over the years I have tried this product-promise strategy with many companies with growing success, especially as platforms such as Facebook have allowed for better targeting of specific customer segments with incredibly precise messages. What was impossible 10 years ago is incredibly easy to set up today: targeted campaigns for very specific audiences, with amazing tracking, which allows you to easily analyze responses to your product promise campaign.

One of the best examples I can think of came from one of our portfolio companies that decided to pivot about four years ago. The team had three different ideas, and before deciding which one to go for, launched three product promise campaigns to the target audience of each idea. All three were in the SMB space, so we expected similar conversion numbers for the ads. Two of the ideas yielded a decent 1% click-through rate. The third idea was an amazing 12%. And there was a similar ratio for the calls to action they tested out.

We had two decent ideas. But one amazing one. The company built an MVP based on the third product promise, got immediate love from the market, and eventually was a very fast exit to the main incumbent in their field.

And the potentially “upset” users who engaged with those early product promise campaigns? They signed up with their emails just in the hopes of getting early access later — and became the company’s initial paying customers once the real product was launched. We saved months and millions by checking our product promise before actually building the product. For startups that rely on speed in order to achieve product-market fit before their runway runs out, this is the difference between failure and success.

How expensive is this process? Not expensive at all compared to writing code. In most cases, a few thousands of dollars spent on campaigns will provide sufficient data to find your validated product promise.

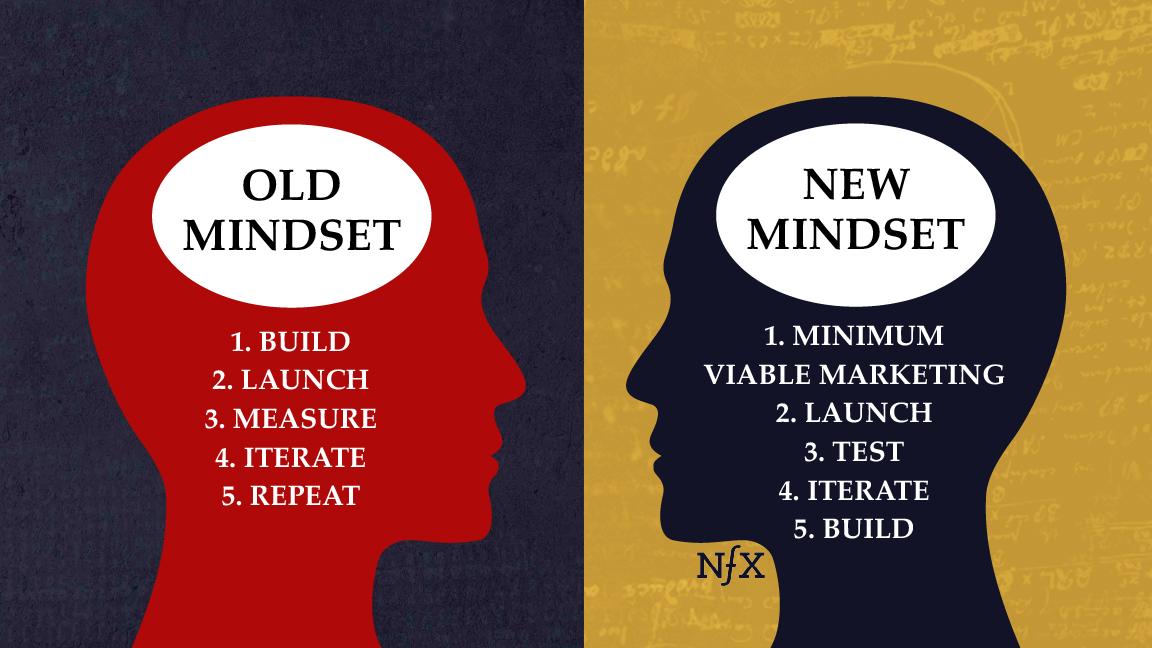

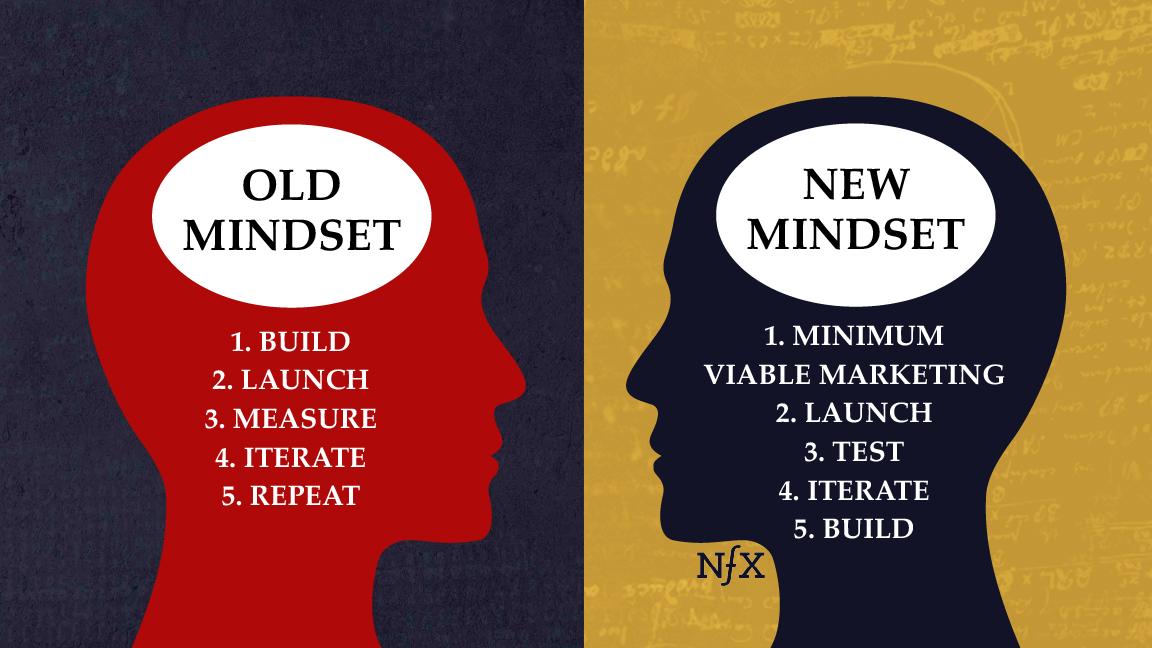

A new order of operations for a new world (with marketing skills taking the lead)

No longer is the startup process: “find a problem, build a solution, market it.” The order of operations has been flipped.

Marketing skills (writing, designing, campaigning, and analyzing) now come in a lot earlier. Even before you’ve written a single line of code.

Today we should all embrace a new reality:

- Find a problem.

- Describe your solution (in words and design).

- Market your product promise until you find a promise that a big enough group of people really want.

- Then build your MVP.

- Keep measuring, building, and iterating — make sure your users are deriving true value from your product.

- Keep building & marketing your way to sustainable growth.

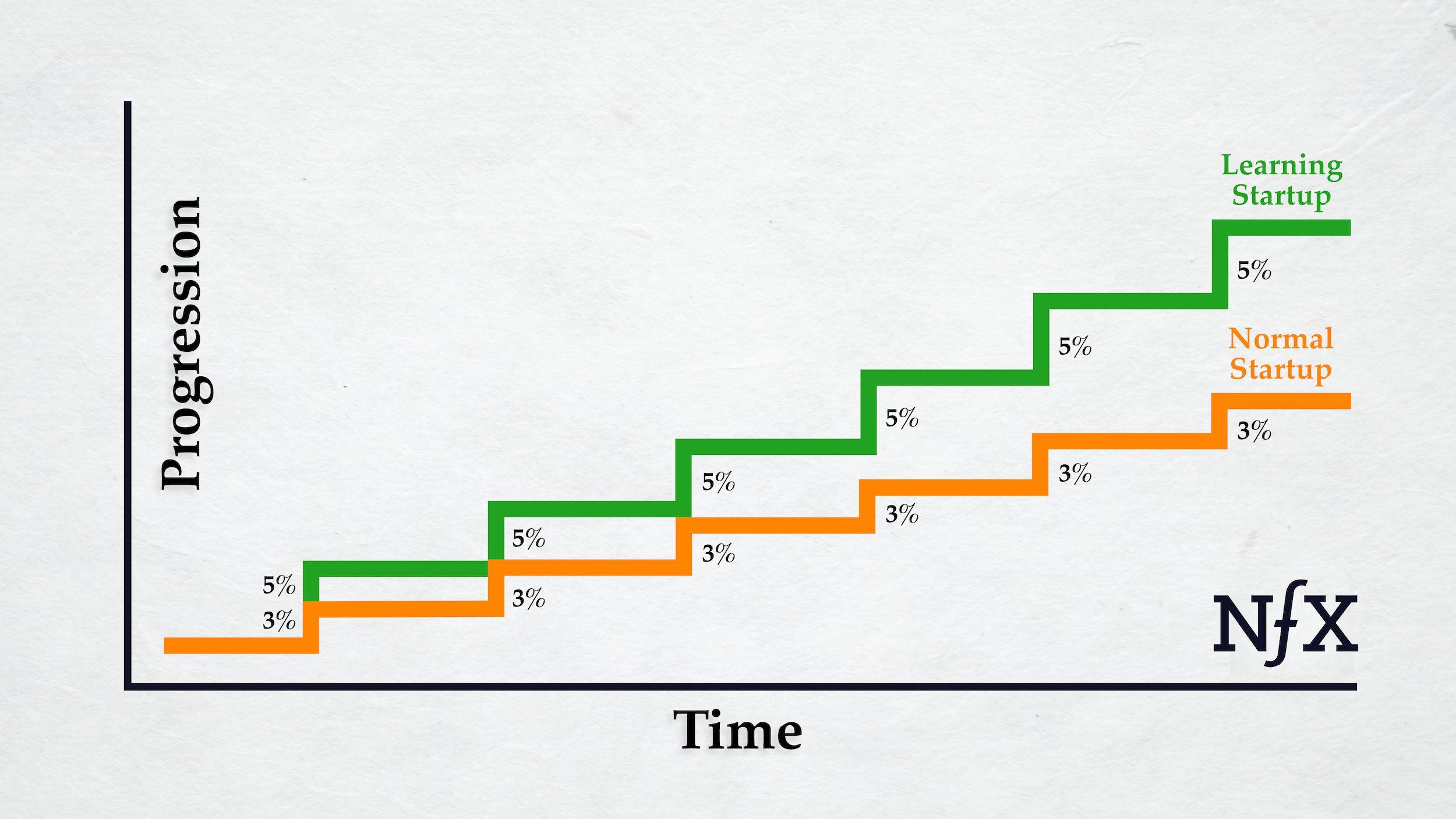

Marketing-minded Founders are going to be the new secret weapon. Their startups will learn how to test a product promise first, and will then achieve white-hot product-market fit — and funding, and engaged users, and yes, growth — that much faster.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.