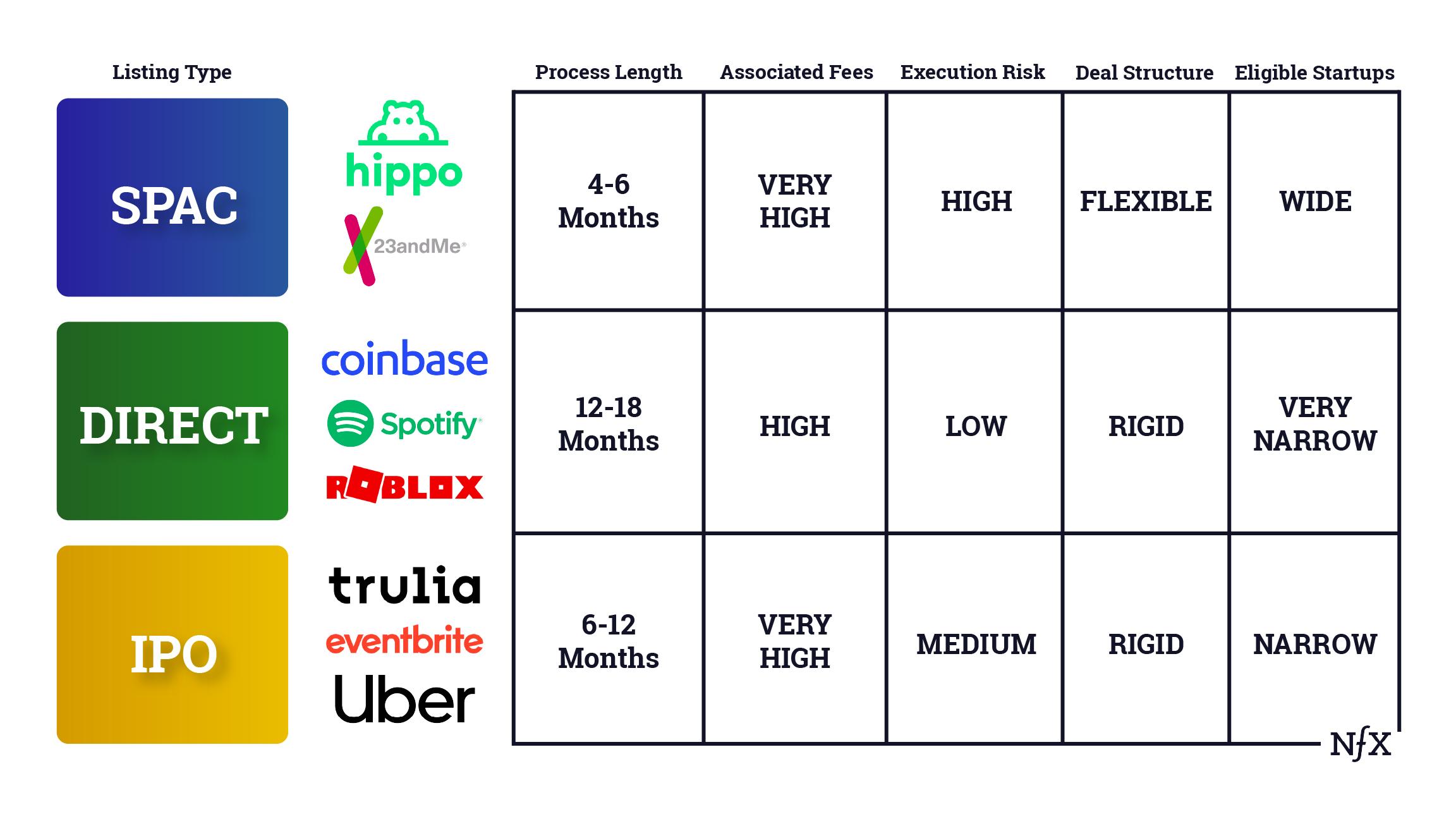

Startups today have more options than ever before — much earlier in their life cycles — for entering the public markets.

When I took Trulia public in 2012, the traditional IPO was really the only viable option, and there weren’t nearly as many tech companies going public.

Now I get calls from Founders saying that they are getting 7 emails every week about going public via SPAC (for reasons to be examined below). They are looking for advice on how to think about traditional IPO vs. SPAC vs. direct listing — and how to even answer the question: Am I ready to be a public company?

Because no complicated issue has just one answer, I sat down with 4 world-class experts representing different views on the topic. The result is this guide of the pros and cons of all the options for going startups who may be thinking about going public soon or over the next few years.

Included in this guide are insights from my recent conversations with:

1. Lise Buyer, known as the IPO whisperer, who has advised many high-profile tech IPOs and famously architected Google’s IPO back in 2004, and also consulted on Trulia’s IPO in 2012.

2. Kevin Hartz: Eventbrite Cofounder; early investor Airbnb, Uber, Pinterest, Trulia, Paypal. Currently Cofounder at A-Star. He is the backer of SPAC one, which debuted last summer, and a second SPAC, two.

3. Julia Hartz: Cofounder and current CEO of Eventbrite, which she and Kevin took public 3 years ago. Notably, one of the very few women to lead a tech IPO.

4. Assaf Wand: Cofounder and CEO of Hippo home insurance, which is going public via $5B SPAC in partnership with Reid Hoffman and Mark Pincus.

Becoming a publicly traded company is often the inevitable evolution for startups that are building disruptive businesses as they look to redefine their industry.

What Has Changed In Public Markets?

- In the 2000s: Companies were being founded and then going public in literally a matter of a few years.

- Around 2005: Then there was an aversion to going public. Companies were staying private much longer and there was also just only really one option – traditional IPO. Even then, it seemed like tech IPOs were a rarity. Lise Buyer wrote an article in Fortune called “Where Did All The Tech IPOs Go.”

- Today: Now it seems that there are so many IPOs or so many SPAC offerings. It almost feels like 2000 again, these companies being founded and then going public in literally a few years. What’s driving that?

Lise Buyer:

- First and foremost, the markets have been incredibly hot. Technology stocks, yes, some of them have corrected early in 2021, but the last couple of years have just been a bonanza for technology companies and the markets have shown a great willingness to take incremental risk and invest in new issues.

- And so it’s been a great market for companies that want to go public. So there was that enthusiasm.

- But I think the real reason that there have been so many of these IPOs in the last, let’s call it, I don’t know, nine months, has been because the markets have proven very receptive and the methods for going public and very different now.

A Note On Staying Private

While this guide is about methods for going public, it’s worth briefly examining the reasons for staying private instead.

Lise Buyer:

- Prior to 2012, when a company had 500 shareholders — and that included employees — it had to file financial documents. There’s something called a Form 10 and the argument was, if you’ve got 500 investors if you’ve got 500 shareholders, they’re all entitled to know how you’re doing. In the early days of its friends and family, they’ll take your word for it. But by the time you’ve got 500, you have to share your information.

- And many companies — I would point to Google and Facebook as great examples — went public when they did only because they were going to have to file all their financial information anyway. And so as long as they were going to have to put it out there, they might as well get the benefit of people’s jaws dropping to see how well they were doing. So they thought, let’s go public off the momentum from those filings.

- But then a huge change happened in 2012 with the Jobs Act — a brilliantly named bit of legislation that actually did exactly what it was promising not to do. In 2012, led by the NVCA, the Jobs Act came to be, which said, “Eh, forget that 500 shareholder rule. You can have as many as 2000 investors before you have to share information. And by the way, that doesn’t include your employees.” And so that allowed companies to remain private much, much longer.

- For many companies including Google (GOOG), that public filing was the catalyst for a public offering. However, the JOBS Act all but eliminated the information-sharing obligation and in so doing, enabled companies to tap an expanded pool of private investors with enormous sums of capital.

- I think part of the thinking was the early investors, again, often led by VCs, wanted to stay in for more of the ride. Frankly, they didn’t want to have to share the steepest part of the growth curve with the public. And so being able to stay private longer seemed like a bonanza.

- And the big public investor said, “Well, okay, if you’re not going to let us participate at the early stage as a public company, then I guess we’ll all get our charters changed and we’ll start investing when the companies are still private.”

- And so you’ve seen a huge increase in the mega rallies where new names to the private markets — names like Fidelity and T. Rowe price and all the other household public company names — started investing privately.

- This means the need to raise capital is probably much less important today than it was five, six years ago in terms of the IPO market.

“Light Is The Best Antiseptic”

The conventional wisdom for a while was to stay private at all costs. That is changing rapidly right now.

Kevin Hartz:

- The conventional wisdom is changing. Whereas what we’ve seen over the years happen often is just round after round of private capital, where governance often can take a hit, poor governance, as we saw in WeWork, we see less accountability to the numbers, to the right growth measures.

- Staying private gives the sense of kind of control, but I think it’s a misnomer.

- The expression is that “light is the best antiseptic” is what comes to mind – in that a company out in the public eye will have much more responsiveness in the business and in the performance.

- And so we’re seeing the market now swing back that pendulum, swing back to what we saw in the nineties, and that’s staying private for a very short amount of time relative to today.

- Capitalism is like a pendulum. It never stays right in the center, it always swings in one direction or the other. From boom to bust, to IPO early, to IPO very late, and we’re just swinging back from staying private at all costs, back that other direction, because those thoughts from the period of the nineties are coming back, having the currency for acquisition, having this kind of marketing event, having this responsiveness to the street, and of open sourcing your business model, that you can gain insights.

- So there are all these great reasons for going public that were kind of put to the side of the previous conventional wisdom of staying private, and the control and ownership that brought.

- Caveat: Of course there’s the example of Stripe, and that is an outlier of a company of massive size and growth in profits that is still private.

It’s not “Am I ready to go public?” It’s “Am I ready to BE public?

Lise Buyer:

- It’s not, “Am I ready to go public?” It’s, “Am I ready to BE public?

- Once you’re public, you can’t miss. Can I forecast my numbers at least three quarters out,” because you go public and you suggest to people you’re going to make $.10 and your first quarter out of the gate, you make $.09, investors are furious and that stain lives with you. It stays with you for at least the next year or so.

- It even took Facebook 18 months to return to its IPO price. And what happens? The stock falls. And what happens when the stock falls? The morale of your employees plummets right along with it. So point one, can you close the quarter in the requisite period of time, which ideal is 10 days. Many companies going public can’t do that. Can you close it in 25 days? Two, can you forecast your earnings out quarter by quarter for the next, at least year, with a reasonable comfort level, and reasonable comfort level translates to, you’re not going to miss (barring some COVID-scale disaster). That’s super important.

- Do you have all the right people in all the right seats? For better or worse, being public requires lots of systems and lots of filing things. And what about a board? You need a board with enough independent members to have an audit committee and to have a comp committee.

- Everybody’s being approached by SPACs. And as I just mentioned, there are so many of them. if you’re getting approached by seven a week right now, it’s going to go up to 14 a week. But that doesn’t mean it’s the right thing for your company after the deal.

- So, most importantly, can you forecast? Do you have the structural wherewithal to operate in the glare of the public light? And do you have all the right people in all the right seats?

Assaf Wand:

- The first question you need to ask: is the company ready to be a public company?

- People always miss out on that because you’re running a company and all of a sudden SPACs reach you. And I go, fine, wow, well, we can be a public company and raise $400 million. That’s amazing.

- But you never stopped to say, do you have the right processes in place? Can you forecast, I don’t know, eight quarters into the future and beat-and-raise your numbers? How well you’ve been doing recently on the beat-and-raise with your board. Do you have a GC that can be a GC of a public company? Do you have audited financial documents for the last two years as a public company? Do you have a CSO in the company? Because you’re going to be attacked like crazy by cyber. Do you have a CFO that can actually do it? There are just a bunch of questions that you should really ask yourself.

- The second question is, is it the right thing for this company to be a public company? We thought for insurance, it’s awesome because we’re in a game of trust.

- We’re going to get a lot of credibility. It’s good for our partnership. It’s good for a lot of stuff. It matters if Pete is calling my call center and selling you and ask, “Who are you guys exactly?” And one of my agents going to say, “Oh, and we are listed on X, Y, and Z.” There’s something that resonates very differently.

- Only then do you look at the different ways to go public.

Julia Hartz:

Three years ago, Julia took Eventbrite public. The company was 12 years old. She was one of the very few women to lead a tech IPO.

- We knew in the back of our heads very early on that we wanted to build something that could be incredibly efficient. We bootstrapped the company and spent less than a quarter of a million dollars in the first two years getting traction and product-market fit.

- We knew that along the way, we would want to become a public company. So that was always part of the plan. And I think I really learned that from Kevin, that the best companies are often public companies, and that’s because those companies have found what makes their business tick, how to meet the needs of their customers, and they couple that with the rigor and visibility of being in the public market.

Going Public: What Stays The Same (No Matter What Structure You Pick)

Lise Buyer:

- For every type of “going public,” the management team needs to get together and put together an S-1 or a prospectus or a document that talks about the company’s business, that talks about the company’s risks, that talks about how they calculate their finances, the MD&A section, which is management’s discussion and analysis, basically, the numbers. All of that’s the same, whatever process a company chooses to go public.

- In a traditional or a conventional IPO, when the company is thinking it’s time to go, it’ll hire a group of bankers. It’ll hire a syndicate. And depending on the size of the deal, that can be anywhere from, I don’t think I’ve seen many that are smaller than five names recently, to some of the bigger companies like Uber probably have 20 names on the company. They’ll hire a syndicate of bankers and they’re hiring those bankers 1) to help them work through some of the regulatory requirements and 2) to help them translate their story from the way management has thought about the business to the way investors will look at the business going forward.

- They’ll also use those banks to help them, and this is where we’re going to get into some of the differences next, to help them market the story and market the stock when it’s time for the actual transaction to happen to a wide group of investors.

- The management team will have to come up with a forecast of how they think the business is going to perform over the next, let’s call it, eight quarters. Generally speaking, it’s actually eight quarters or three years. And that’s really difficult, particularly for companies that are growing at the rate that so many of these are growing

- So one of the hardest parts is coming up with the forecast because for heaven sakes, most rapidly growing companies have a hard time forecasting out five weeks, much less three years or eight quarters.

All of that’s the same regardless of what structure you pick. Now, let’s get into specifics, where the differences will show up.

1. Traditional IPOs

Why do companies go public via the traditional IPO? A solid public launch not only enhances the corporate treasury but also an entity’s reputation, brand awareness, flexibility, competitive position, and quite possibly, the rate of growth.

There are pros and cons to being public but for those solid enough to earn the right to be public, there are many more pros.

Lise Buyer:

- Some companies go public because they just wanted to raise as much money as they could to pour into the business to grow it. They wanted a liquid security because that was an implicit deal they’ve made with their employees.

- And also because they wanted to be able to use the stock as a currency in M&A. When you are a private company, it’s very difficult to get agreement on what stock is worth on any given day. Whereas when you are a public company, the market is valuing your security every single minute of every single public trading hour of the day. So you know exactly how many shares equal how many dollars. So, the currency is clear.

- Some want to go public just because it gets a lot of publicity for them.

- Those are the most popular reasons motivating most companies to go public. Every so often you have a company where the management team and the Founders don’t really want to go public, but the early investors are: “Let us out now.” I would say that’s the fourth general reason why companies go public – they are marched there – but it’s less common.

Pete Flint on why Trulia went public:

- The first reason was the scale of the business at the time and that we needed to raise capital for it. We felt that the public markets were more receptive than the private markets. Raising in the public markets was just more attractive at the time.

- The second reason was the branding credibility event which mattered in the eyes of employees (for recruiting and retention) and in the eyes of customers evaluating us.

- And then thirdly, it was the ability to do M&A. Having a liquid currency for M&A was a major reason.

“If You Can Make A Human In 9 Months… “

Julia Hartz:

- IPO-ing was always on our list of things we would do at Eventbrite when we dot, dot, dot. And the dot, dot, dot for us was reaching a certain revenue threshold and having visibility and confidence that we could continue to drive the business.

- And that meant that we understood the levers that drove our business, which meant that we had really kind of nailed all of our operating metrics. And I think that going into that decision, it just wasn’t a hard decision for us because we had always figured that once we had crossed those thresholds or achieved those milestones, that we would be looking to start the IPO process.

- It’s different for every company and I don’t actually think that it’s a certain magic number for every company. For us, it was when we had a line of sight on $300 Million in net revenue, and also when we felt that we had a line of sight into what it would take to be a profitable company. And most notably above those revenue metrics were our creator numbers, retention numbers, consumer growth, those were all really important inputs into that revenue threshold.

- We benefited from having a team that had largely been operating together for more than five years. And I think familiarity and cohesion as a team were really important in building up to the IPO and going through that process.

- There are a lot of Founders who are kind of negative about going public because they think it will change the way that they run the company or the culture. I don’t think I found anyone who told me it was a good idea. It sort of motivated me in a way to be a contrarian.

- So I set out with some sub-goals. Obviously, the goal of an IPO is to raise money in the public markets. And there’s all sorts of inputs and probably some really unnecessary long processes in that, which I’m sure we’ll get to when we talk about SPACs, and there’s a lot of cooks in the kitchen, but I knew going into it that if I was going to put nine months of effort and distraction into this fundraising, I was going to get out 10X, the value.

- I had had two babies. So I knew that in nine months, I could make a human. This was going to be nine months to get to a place that needed to be pretty extraordinary.

Building The Infrastructure You Need

Lise Buyer:

- I think companies that can pursue a more traditional IPO path may find the length of time and rigor that it takes to get there is actually helpful … it helps them build the infrastructure that they’re going to need.

- Wall Street you will measure you by your P&L, your balance sheet, and also your KPIs or your non-gap metrics or what else do you, as a management team, look at on a quarterly basis, generally, could be annual but, on a regular basis to see how the business is doing?

- And then, of those things that you watch internally, what would you be willing to share to the public that both would help people understand how the business is doing and wouldn’t be overly sharing with your competitors? And of course, understandably companies don’t usually think about that.

- But the earlier you start thinking about things like the number of customers, number of customers over $100,000.00, cohort analysis, I don’t know, there’s all kinds of things. The sooner you start thinking about what you do want to share and what you don’t want to share, the sooner you can start collecting data internally on that which is important to you and what you’re going to want to share, and that’ll save you angst later.

- And the other thing to think about before you go public is do you have any policies in terms of secondary share sales. The more you can know where your shares are, the better off you will be if and when it’s time to go.

- And I should toss in just in case anyone’s wondering, I am a consultant to company’s listing for the first time. It doesn’t make any difference to me whether you choose a SPAC, a direct listing, an auction or a traditional deal. I have no hound in the hunt. It’s just you really want to see what is in the best long-term interest of the founder and the team, because too often they end up on the shorter end of the stick.

Differences Between Traditional IPO vs. Direct Listing and SPACs

Lise Buyer:

- With a traditional IPO, when you hire your banks, each of those banks generally had a research analyst, and the research analyst was meant to be an expert in the area that your company lives in. So it could be a semiconductor expert. It could be a consumer products expert. It could be a SaaS expert.

- And those analysts were meant to listen to your story and to reflect back to you what they heard, what they think will be of interest to public investors, and also what they think of your forward model. Companies very carefully will give their model to research analysts in the traditional IPO.

- And the analysts are asked to come up with their own versions of those models. Well, “We think you’re being overly optimistic here and we think you’re being overly conservative here.”

- It is then the analyst community that will go out to the buy-side investors, the Fidelity’s and the Capital’s and the BlackRock’s and all those folks and say, “Hey, this is what we think the company is going to earn.”

- The company itself will not share its forecast. Huge difference.

- By contrast, for a direct listing, companies will hire many fewer bankers, maybe two, maybe three. Now increasingly. they’re paying a fleet more to write on them, but that’s separate from the listing, frankly. And the company itself will go out with its own forecasts.

- And the same is true of a SPAC. With a SPAC, it is the company’s forecast that is used to market the security as opposed to analysts’ forecast.

2. Hybrid Auctions

Lise Buyer:

- I want to bring up hybrid auctions right after traditional IPOs. In the case of a hybrid auction, management has much more data about which accounts are interested in the security at which price, and management has the total say over to whom the shares get allocated.

- With a hybrid auction, this is probably the biggest difference – investors have to say, “I want X number of shares at this price. I want X plus Y number of shares at this price.” Each investor has to give the management team, not the sales force of the investment banks, but the management team, their demand curve. How many shares do they want at each price?

- And the management team for those bankers will help them put together a message spreadsheet that says, “Okay, if you price your deal at 50, these are the investors who are in and you could probably price this deal at 85 if you wanted, but you will get a whole bunch of investors you’ve never heard of who’ve never met you. And we know that they’re just momentum players. Or if you price down at again, 50, for the sake of the conversation, you’ll get all the professional institutional investors who probably will come in for your IPO and be there in the market afterward. And you can see if you price it 50, this is who you get. If you price it 51, this is who drops out. If you price it 52, this is who drops out.”

- Management teams have just exponentially more information about which kind of investors are interested at which price point. And they have that information prior to choosing at which price they want to go public.

- In some ways, the hybrid auction is doing the price discovery piece and investor selection piece that was typically shielded from management teams by the investment banks. And so ultimately they can use technology as opposed to using the knowledge and expertise and relationships of a bank.

- There is some nuance there, but in a nutshell, hybrid auction gives management the most information ahead. Direct listing gives them the least information.

3. Direct Listing

Lise Buyer:

- In the case of a direct listing, a couple of things are different. One, the issuance of the forecast, as I mentioned before, comes straight from the management team.

- They will have a big meeting, maybe six weeks prior to when the actual transaction is going to take place. And it will be streamed and anybody who wants to can listen to them tell their story and put their forecasts out there.

- In the case of direct listing, management goes out and does the best it can to convince investors to take part, and then they throw the cards up in the air and they wait for the day of the deal to see who’s going to buy it and at what price.

- They have no control over either the price or who gets the shares.

- It’s a little more challenging because one of the reasons that companies don’t put their own forecasts out when they’re doing a traditional IPO or hybrid auction is because they have legal liability for anything that they say during the sales process of an IPO.

- When you are selling stock, you can’t be off on your forecasts. If you say SG&A is going to be 22 million next quarter, and SG&A turns out to be 22.5 million next quarter, you can be sued for that, so that’s why they have the investment banks put out the forecasts rather than the companies themselves.

- Spotify was the first direct listing. That was a great example of a company to go do a direct listing because the people who owned the stock when it was still public were the record labels. The record labels are not institutional investors. They’re interested in music. They didn’t want to be portfolio managers. So the direct listing allowed them to sell out relatively quickly what they own to get liquidity for the company and to frankly, put big honking liquid dollars in their own bank accounts and to move along. Didn’t really matter to them who owned the stock afterward, as long as it wasn’t them. And the price, $1.00 or $5.00 here or there, sure, everybody wants more, but again, it wasn’t critical for them. So that was a great example of a company where the early investors had totally reasonable reasons to want to get out.

- Asana is another example of a company that wisely chose Direct Listing. The largest shareholder is also involved on a day-to-day basis. He’s the opposite of Spotify. He’s not trying to get out. He’s just trying to create a liquid market for his employees. And again, since he’s the biggest shareholder, if the stock goes out with a great price, good. If the stock goes out with a slightly less price, he doesn’t care. And if anything untoward happened, he could be right there to buy shares back.

- But those are the unusual companies. There are certainly others, but those are unusual direct listings.

- By contrast, the regular IPO route does get you more attention, and if part of the purpose is to build the brand, you might want to take a more traditional route.

4. SPAC

A SPAC is completely different from the rest. SPACs have been around for a while, but over the last year have become an important part of the landscape for tech companies to go public.

Lise Buyer:

- A SPAC is a shell company that raised money for the sole purpose, the special purpose to acquire another company. Right? I mean SPAC = Special Purpose Acquisition Company. That’s what it stands for. It’s a shell that raised money to buy an operating company.

- With a SPAC, a company has gone public. The SPAC has gone public.

- It’s raised $300 million, for instance, and it doesn’t have any operating business at all. So then its job is to go out and find one and have that operating business merge into it.

- So its initial entree as a public company happens because it merged into a public already trading entity.

- Historically, it was companies that probably couldn’t get public the regular Traditional IPO way. Maybe they were in gambling. All the cannabis companies went public via SPAC. Where there was some legitimate fear that they wouldn’t be able to get public any other way.

- Over the past year, that has changed a little bit.

- And what I mean by that is you still don’t see the best of the best going public via SPAC, but it’s certainly the promise of a SPAC. If you’re Pete Flint and you’re running Trulia, this SPAC’s going to come to you and say, “Here’s why you want to do a SPAC instead of an IPO. It’s quicker and we will guarantee you the price upfront. So you don’t need to wait to see what the market’s going to pay for your stock. I’m telling you your company’s worth $5.6 billion. We can shake hands on it right now and go on our merry way.” And that’s part of the pitch.

- I think on the SPAC route, it is companies that just want to get the dollars in hand that are attracted to the high valuation that they agreed to with the sponsor of the SPAC, the folks who took the shell company public and are just in a hurry to get out there.

Kevin Hartz:

- I’m obviously biased towards the SPAC route, but at Eventbrite, I went through the traditional IPO route, and while it had its challenges, was a good experience for us.

- The SPAC advantages as a public company is that you can forecast out, you drop in a detailed presentation to the world upon announcement, and you give projections.

- In a world where traditionally a company going public strangely can’t give forward projections, here is a great way to help guide the street and give a better model of the business. That’s one great advantage.

- The second I’ll just say is really speed to consummating the transaction. It’s just something that we spent many quarters working on a traditional IPO at Eventbrite, as well as XOOM prior, and being able to streamline that, but yet still cover all those areas is a big benefit for companies.

- Then, there is certainly price and that is something that, we had the IPO pop at Eventbrite, where we opened much higher than where we priced at so we’ve left money on the table.

- In the case of a SPAC, you are actually setting your own price. You’re setting a price that is not kind of thrown at you in the last 24 hours of a process, but something that you carefully and cautiously modeled out and put together. Those are just a few of the SPAC advantages.

- But as of April 29th, we’re on the bust side of things right now. The market has cooled tremendously. There’s been some regulatory action on behalf of the SEC. There’s more scrutiny on behalf of the financials that is being done on behalf of the SEC and the market.

- We’ll undergo these kinds of boom and bust periods until we find the right spaces and that the right companies are going public. If they’re kind of C and D players, that’s not sustainable and that will be weeded out by the system of capitalism in a very short amount of time when these companies start missing their earnings.

- But the case of Eric Wu and Opendoor, he did have an operating history. They have large losses, but they have an operating history. They’re selling a number of homes each week. What they really needed was a great amount of capital in a short period of time. They timed their SPAC extremely well. They were able to raise a large pipe along with that. That’s a poster child for great execution on it and the company is, even after the SPAC correction is still worth, I believe, north of $10 billion

Examples of SPACs

Lise Buyer:

- Let’s look at Virgin Galactic. Let’s look at the electric car or flying car businesses that are going public via SPAC. What do they have in common? There’s no revenue yet. And so they are much more difficult to value by traditional public investors because there’s so much left to be proven.

- Even Opendoor, it’s just beginning to prove its model, frankly. And so companies that are earlier in building out the business, can go public sooner if they choose a SPAC.

- And then just thinking through the SPACs, the number of perhaps, companies who have longer operating history and more traditional types of companies with good revenue that are choosing the SPAC path…

Pete Flint:

- One example would be Hippo, the insurance company. Assaf Wand, who we had on the podcast, is taking Hippo public via SPAC with Reid Hoffman and Mark Pincus.

Lise Buyer:

- One of the enticements for an operating company to merge into a SPAC is, “Hey, you’ll be public right away.”

- And the problem is, most companies aren’t ready to be public right away. You remember all that Trulia had to go through and I think Trulia was even pre Sarbanes-Oxley, but to be ready to operate in the public spotlight because you don’t get to make a mistake.

- And there’s a lot of systems that need to be upgraded and there’s a lot of effort that needs to go into closing the quarter, improving your numbers.

- And frankly, many of the companies choosing the SPAC route are not ready for that and are going to have to lean very heavily on their new owners in the form of the SPAC sponsors to help them through that process. That’s why Reid Hoffman is obviously somebody who will be terrific at that, because one can presume he’ll hang around and he will help his companies achieve success even after they’re public.

- And the other thing to think about is the SPAC sponsor may say to you, “You’re worth $5 billion,” but those are just words. After you close the de-SPAC transaction, it’s still the market that’s going to value you and it may or may not have any correlation to what the initial sponsor said. And you are still locked up. You didn’t get to sell all your stock. You didn’t get to realize the $5 billion. So it’s worth recognizing that there may be unicorns and rainbows out there.

So What’s Happening Right Now With SPACs?

Lise Buyer:

- Of course, bigger picture, the SEC is getting involved now. Again, remember in a traditional IPO, the forecasts are put out there by the investment analysts of the bank. So the company does not have liability unless real malfeasance can be proven.

- Whereas SPACs have been going public saying, “No, we’re merging into public companies so our forecasts are covered by those Safe Harbor rules.”

- And the FCC is starting to say, “Yeah, no.” We’re looking into that. But we think if you put out five years’ worth of forecasts, you’re going to have to take some liability on those numbers in case they turn out to be pie in the sky.”

- So within the last just few weeks honestly, the liability issues and the background “paperwork” for lack of a better term, on SPACs has been ramping up dramatically.

- Will it be something to go away in the next 2-5 years? I think the SPAC frenzy is going to take a bit of a powder here while people figure out what the new regulations are, what the liabilities are. And I think we’re going to see something fascinating happen:

- When those shell companies are raised initially, they promise the investors that they will find a company to merge with within, generally speaking, 24 months. Some of them are 18. Most of them are 24 months. And a lot of those SPACs were raised in the same week. I think there’s a number of 464 SPACs right now looking for something to buy and they have to get it done in now the next 20 months. So that’s going to be a lot of fun to see what happens.

- Many more people are looking to buy operating companies frankly, than there are operating companies ready to be bought. So that’s thing one.

- Thing two is, in the event that the companies, the SPACs, don’t find a target, they have to give the money back. So it wouldn’t surprise me if some of them end up giving the money back. For most of us, it’ll turn out just to be a blip.

- For some founders, the SPAC exit will turn out to be absolutely the right thing.

- For many, I don’t think so, but there’s no easy generalization to be made. It’s a one-off.

Are SPACs “Sticking It To Wall Street?”

Lise Buyer:

- A lot of the narrative around SPACs has been “Sticking it to Wall Street and helping founders and helping employers and helping early-stage investors.” But the politest phrase that comes to mind for me is: That is absolute utter nonsense.

- Let’s look at who Wall Street is. Who are the biggest investors in IPOs? BlackRock and Capital and Wellington and T. Rowe and Fidelity. And whose money is it?

- It’s the pension funds. It’s the union funds. It’s all the people who were able to put $1,500.00 into a mutual fund account, at some point hoping to send their kid to college. It is the aggregation of the investment capital of all the little guys out there. There is no Mr. Fidelity. Well, there was a Mr. T. Rowe, but he hasn’t been with us for a very long time.

- So when they’re “sticking it Wall Street” what they’re doing is sticking it to the general public investor. And so the narrative is just totally backward.

- Those who are invested in the venture funds, and again, increasingly, there are some endowment funds in those, but it’s also a lot of high net worth folks in venture funds.

- There will be some winners and some losers, but when you say you don’t want Wall Street to make any money on an initial public offering, what you’re saying is, “I don’t want the little guy to get jack.”

“Similarities to BTC”

Kevin Hartz:

- I see my job as looking for new phenomena, new companies that are emerging that are going to really have an impact on the world. Bitcoin, cryptocurrency, kind of emerged, and was this kind of strange, and hated by many, phenomenon, which now has a trillion-dollar market cap.

- And SPACs are, similarly, they were this strange kind of instrument that, it’s not as reputable background, that we’re coming into the mainstream over the last year.

- And so, the job or my mission and quest here is to help this form into a real industry of helping private companies get into the light of public markets.

- So it’s kind of like VC in ’80s and ’90s was this backwater niche industry, but obviously today it’s clear venture capital has really transformed the innovation economy.

- And we see the same with SPACs, and it’s going through its boom and bust phases right now, but we all know from our experience in tech that that’s just how the world works.

How Should Founders Think About SPACs

Lise Buyer:

- I think the Founders should know that the ball is in their court. Do not agree to merge with a SPAC unless:

-

- You like the valuation.

- You think they can justify the valuation.

- And you believe that the sponsor of the SPAC will truly be there to help you.

- Worth having a conversation with the SPAC sponsors, just to see what they have to say and how they value you. Then in your own mind, you might want to tone it down a little bit and assume that that number may or may not be real.

- Secondly, a lot of banks will come around and say, “Let us help do a de-SPAC process for you.” And they’re charging astronomical fees. So am I allowed to say be a hard-ass? Be pretty tough on negotiating fees with any bank that’s going to represent you because we’ve seen cases where a bank will come in and say, I’ll take care of this for you for 70 million bucks.” And we can negotiate them down to $15M, which is still a lot of money, but it’s not $70M.

- So go ahead, have a couple of meetings. Don’t sign anything. Don’t make any deals, but see how they’re viewing you and ask them questions, but just be skeptical of that valuation.

- I guess the second piece of advice is: If you like what you’re hearing, be tough with them about, “How are you going to help me transition to becoming a public company? And then in the early quarters, to operate as a public company? Are you here just for the transaction or are you really going to stick around to help me make the transition?”

Assaf Wand:

- We started being bombarded by different SPACs last year. And in the beginning, we nudged them all out because we thought it was the bottom feeders of Wall Street. I don’t know how else to describe it. That was the perception in the market.

- And then things made us think about it differently. One was: Why is it so good to be 25 times oversubscribed? Well, that looks like a very weird thing for us to say: I need an analyst to present my basic forecast instead of me talking to the investors and tell them what I see as my five-year forecast. There was just something in the process that didn’t really gel with us well enough.

- So that was one. And then on the other side, some of our current investors and people that I think the world of, started setting up their own SPACs.

- So Ribbit Capital which I think are amongst the best fintech investors around and Micky and Nick are amazing. I was like, “Whoa, where did this came from? Why did you set up a fund as SPAC.” And Dragonia as well, which is also an investor. And Jared and Mark are best-of-breed.

- So I could have a discussion with people that I trust to get another point of view and the mindset, so that helps us educate.

- So we were looking at it and we became a lot more: Okay. That’s actually interesting.

- I do think that there are some components that they put too much weight on the benefit of a SPAC versus an IPO, which in hindsight, doing the process now, I think it was a disproportionate amount of weight.

- Then we talked to Reid Hoffman and Mark Pincus who, you know, built a couple of successful companies – and thinking about that and came to the realization that they want to do a SPAC.

- The biggest for me was: Can I have someone who can help me with that transition into the public markets. And we came across Reid Hoffman and Mark Pincus, and really, the optionality to work with Reid and Mark is… I’d be the dumbest person in the world to resist that optionality.

- They call it being VC on scale to help a company – to stay there for a long time to align, to join the board, to basically help this company go, was a full alignment and the meeting of the mind.

“An IPO Is Not An Exit” – And Building Durable Businesses

Kevin Hartz:

- There is a company as a case study that went public in the 1980s at a 500 million valuation, and there’s a company in the nineties that went public at a $500 million valuation. And that was Microsoft and Amazon, respectively, both worth, that have surpassed that magical trillion-dollar market cap number.

- So an exit is a misnomer.

- I think it was a term that venture capitalists used, that as soon as the company went public, it was their fiduciary responsibility to distribute shares, and thus, the term exit came about. But today, the reality is, is that it’s just the beginning of a much longer journey.

- We are here to build enduring businesses that last for generations and to that end, there are really no differences.

The beauty of all these options is that every Founder and every management team can make their own choices now. Different companies are trying to optimize for different outcomes, and now have various powerful vehicles for financing those companies into high-value, durable success stories.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.