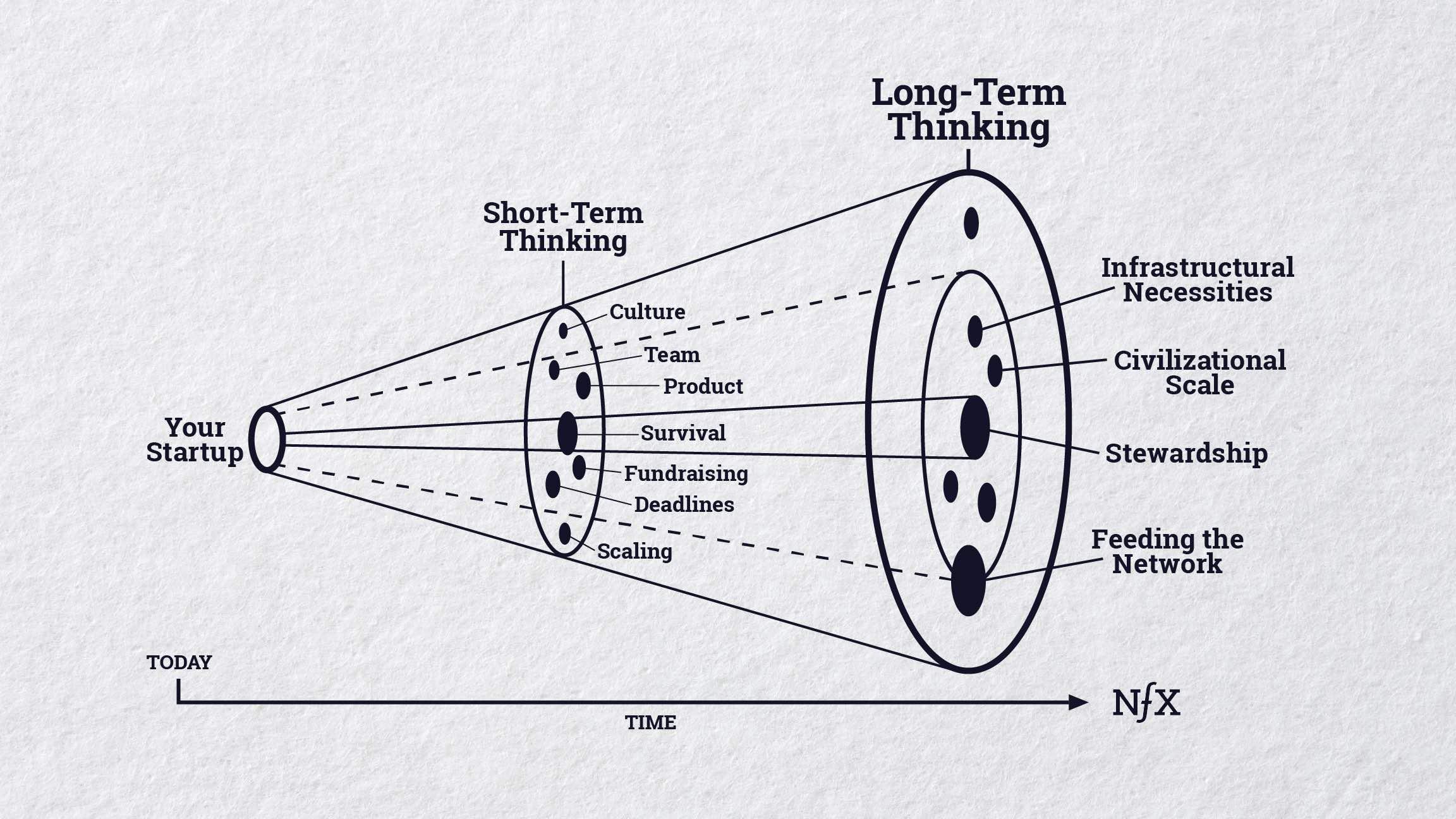

By necessity, Founders are rooted in the “here and now” mental framework required for launching a new startup.

But *great* Founders do something different at the same time: They are obsessed with what will endure 10 or 50 years from now.

Kevin Kelly helps you rise to that level. He is the legendary tech thinker who lives in the future — he co-founded Wired back in 1994 when only a few saw the digital revolution coming. In his best-selling books he told us all our future before it happened (The Inevitable, What Technology Wants, and New Rules For The New Economy).

My conversation with him, highlighted below, and in the podcast, uncovers not just how to be the best, and “the only”, but also — the importance of building something that endures.

Startups and Tech Companies, Are You Being A Good Ancestor For Future Generations?

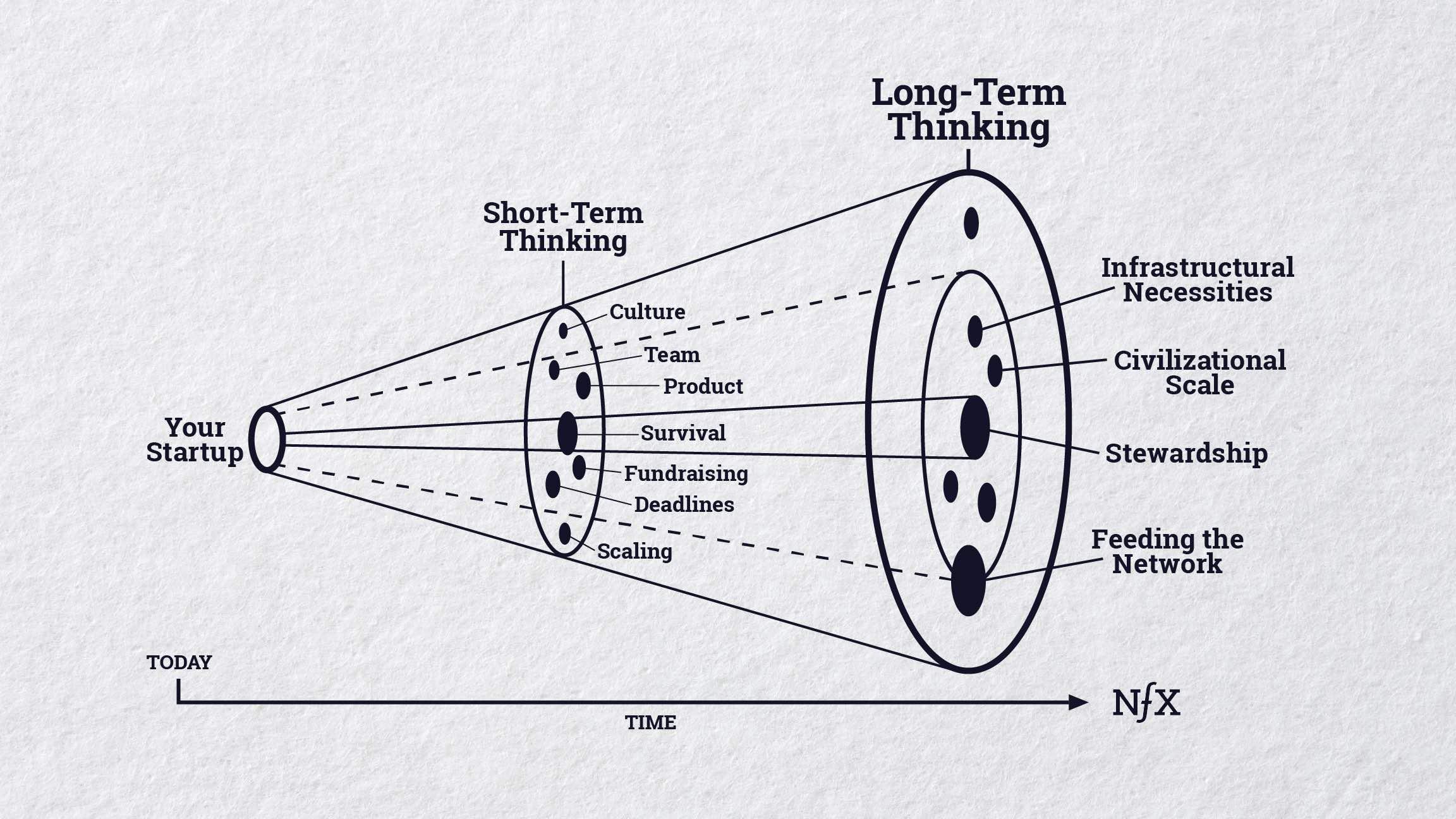

- One of my missions is to be a good ancestor — to try to incorporate more of a long-term view. This is counter in some ways to the mission of a young startup, which is often battling for survival.

- There is a very immediate now-oriented framework for startups. That’s understandable, but I think if you want to zig where others are zagging, and this was Jeff Bezos’ idea, if you think about things that don’t change very fast, if you operate on a longer-term perspective, you have an advantage because everyone else is completely short-sighted.

- I think that taking a longer view of things can set you apart.

- What happens when you take a longer view is you think less about things like competitors, and you think more about civilizational scale, infrastructural necessities, and feeding the network. You focus on all of these other things that, in the long run, will be more important, and may liberate you in having an approach that others don’t.

- Maybe there are institutional things that we can do as a society to help early-stage companies not be so short-sighted, but I think it’s hard to do it on their own just because of the pressures of getting started and survival.

- It might be something that we have to invent other kinds of institutions for. Governments can certainly do some amount of it, but they’re not allowed to fail. Non-profits, to some degree, are a third category that could do longer-term stuff, but they don’t have that much power.

- We can invent institutions that have the legal, social, and economic power to do things in the world that have a longer term.

Stewards Of The Future

- It may be that longer-term thinking may not be something that we should expect of earlier stage startups. But what about bigger, more successful networks?

- So you get companies with network effects that are going to be around a long time because they’re hard to dislodge, whether it’s Craigslist or Facebook.

- At some point, the people running those companies have to emerge from their chrysalis of short-term thinking into being more of a steward of the future.

- They have to take that emotional journey and take that maturation process.

What Can You Do Now, That Will Pay Off In 20 Years Or More?

- One of the things that we don’t do very well is long-term research. There are very few experiments that last more than four years, which is the average postdoc tenure.

- We don’t have a very good facility for doing long-range research that might take long to do, something that may take 20 years to pay out. So you’re funding some kind of basic research that you have no expectation of making sense or being developed at least for 20 years — and maybe during your lifetime.

- To the funders and the government, that may look like a waste. You might need another kind of an institution that would protect that research for the duration, or maybe there’s some way we can turn the value that’s created by that research and have it come back and pay into that instead of just going to all the entrepreneurs who bank on it.

- This may not be front of mind for the entrepreneurs starting things, but it should be. If they have any level of success, someday they’ll be the reigning, dominant tycoons.

- And by the way, your ancestors will thank you.

A Startup’s Chief Advantage Today

- One of the surprising things that network effects do is imprison the winners of those network effects in a prison of success.

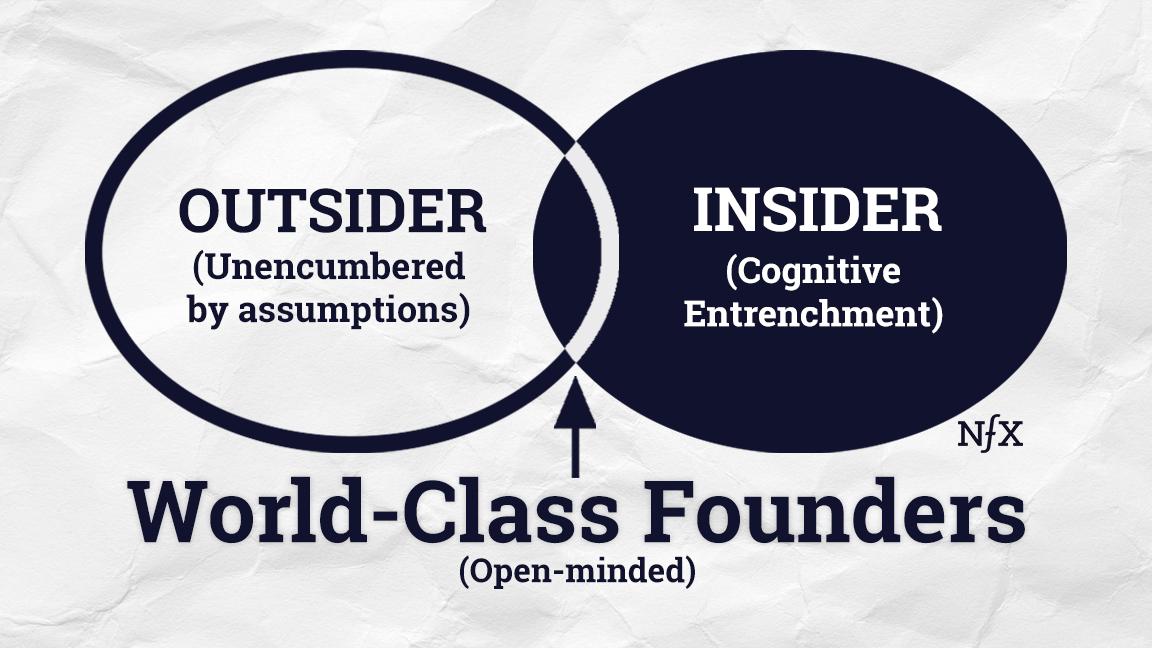

- In conversation with Pete Flint, Adam Grant called this a cognitive entrenchment — when Founders get too attached to their existing patterns of thinking, they become prisoners of their own prototypes.

- They’re imprisoned by their success because the truly disruptive game-changing innovation breakthrough business is going to come from outside of their core success. That’s just the general pattern.

- The reason why it comes from outside their success is because the more successful a company is, the more likely they are to use money to try to solve a problem. There’s an old Jewish saying that any problem that can be solved with money is not really a problem. And so what happens is that big companies try to buy solutions.

- Now, the startups would like to do that too, but they don’t have any resources. They don’t have any money. They don’t have people. They don’t have anything.

- So they have to be really scrappy and they have to invent and figure out and innovate a solution without resources. And that is a solution that works.

- That’s the solution that is going to spread and succeed because they have used genius to solve it instead of money.

- The big companies then say, “Okay, we’ll just move over there and take over,” but the problem is that to do so, it means that they have to come down from the optimization they have been working so hard to produce. The problem is the new innovation is always in a territory where there are low profits. The excellence that they’re all working toward, the optimization and the efficiency, is not useful here.

- It’s unproven. It has a high failure rate. It’s a terrible place to do business. The only people who do business there are crazy startups. No sane person is going to be there.

- To move a successful big company down into that crazy innovation territory requires devolution. It requires going backward. It requires undoing their optimization in their quest of excellence. It means doing less excellence. And there’s nobody or nothing in the company that is very successful that is going in that direction.

- They can’t really de-optimize and move their thinking and everything else into this territory where it’s terrible business. What happens is the startups are left to keep doing things until they pass some threshold of basic viable customer satisfaction. And at that point, it’s too late, they’re off to races.

- That’s the advantage for startups. What that means for startups is you need to amplify, augment, and enhance the fact that you have a lack of resources. That is actually your chief asset.

- True innovation you can only get to if you don’t have the resources. You have to be scrappy and ingenious. You’ve almost got to be a desperado.

“Don’t Be The Best, Be The Only”

- The one thing that I’ve been impressed by in talking to many high achievers, not just entrepreneurs, but all classes from actors, singers, musicians, business people, and writers …. the more curly-Q their career path was, the higher they went.

- Almost none of them have a direct path. Anybody on a direct path I would be skeptical of.

- I think a meander is almost essential, but certainly conducive to really becoming a world-class individual and an only.

- I resonate with this idea that is often attributed to Jerry Garcia of The Grateful Dead, which is “Don’t be the best, be the only.”

- I am really interested in companies and individuals who are the only, who’ve become the only. And that to me is a much better place to be than just merely the best.

- The only would be this guy who does “Magic for Humans”, Justin Willman. He’s a magician with a very special style. He’s a street magician that’s wrapped up his magic into themes about fatherhood or motherhood or telling the truth. As far as I can tell, he’s the only person doing it. That’s a niche for him. It’s a certain kind of magic and a sermon.

- He’s an only in my book. He’s not really competing against other magicians. He has this little niche to himself.

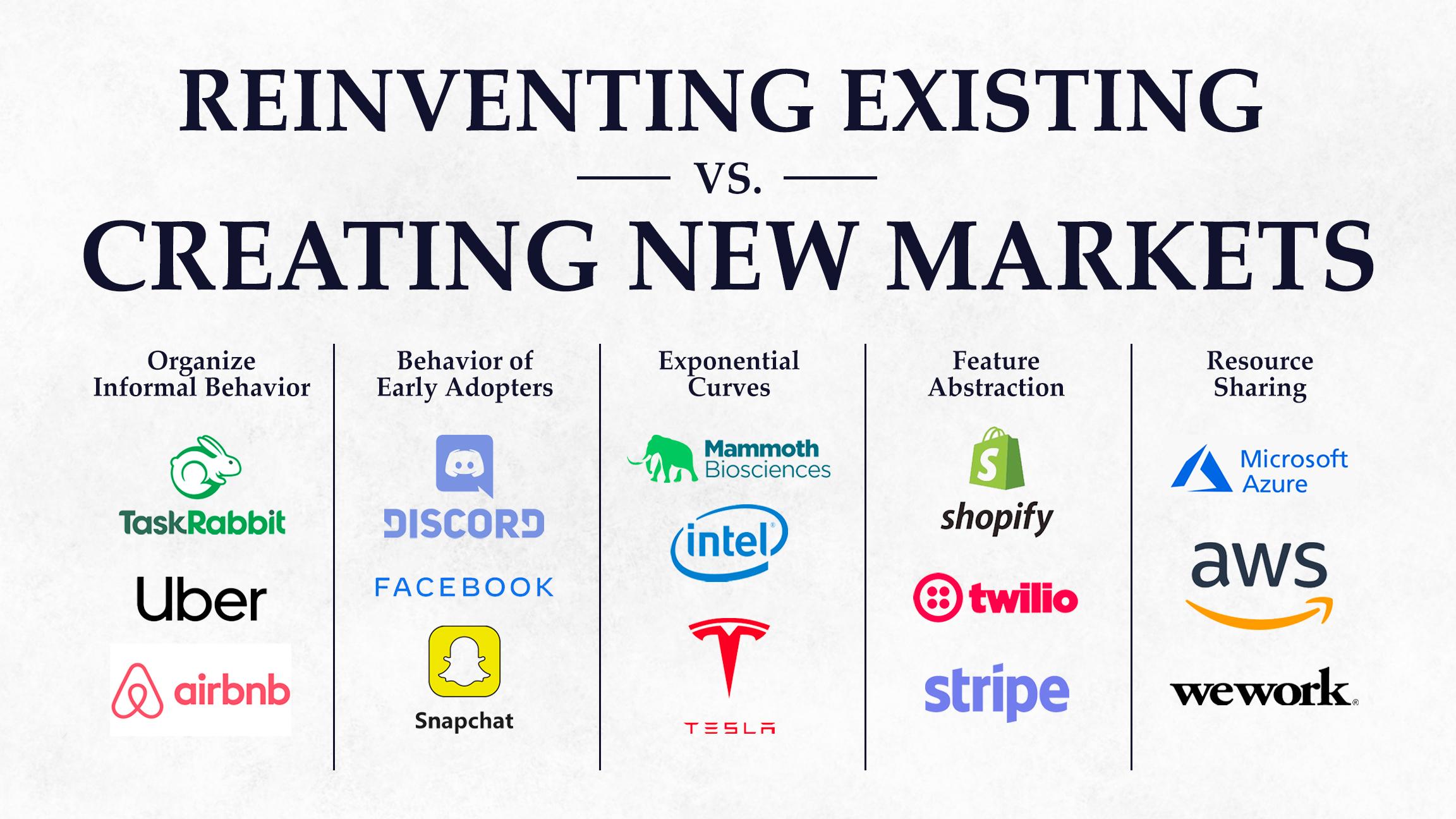

- Both as an individual and as a company, you want to work on something that nobody has a name for. When there’s no name for what you’re doing, that means that there’s no category and you have difficulty explaining to people what it is that you’re doing. That means that you are on the path to the only because there’s no category.

- If you’re trying to become the best basketball player in the world, that’s a zero-sum game. There’s only a limited number of major league players and it’s fixed. But if you were going to become the best horseback golf pro, I’m just making something silly up, you’re not competing against anybody. That’s one of a kind. You are making your own niche. You don’t have to displace someone or take someone else’s job.

- But, you have to be doing something that you are equipped with talent and skill to do.

- When you try and do that as a company, that’s a high bar. Not only do you have trouble telling people what you’re doing or convincing investors that you will succeed, but you will also have to be incredibly self-aware of your own abilities and talents.

- It often will take a long time for you to arrive as an individual to understand what your gifts are. That’s where the need for meandering comes from. That’s where this long path comes from.

What We Saw At Wired, That No One Else Could

- The major parents of Wired were Louis Rossetto and Jane Metcalfe. I was trying to put out a magazine, a similar kind of magazine. It was called Signal. But the difference was I was talking about ideas and tools in this new emerging world. And Louis and Jane, their creative genius was saying, “No, no. We want to talk about the people who are making the ideas. We’re going to have people on the cover.” That was absolutely right. That was the genius thing.

- The editorial proposition was very blunt. It was, “There is a revolution coming and you’ve got to wake up to it. This digital stuff is going to become the central thing.”

- Now that seems perfectly obvious to us now, but believe me, the resistance to that back then was unbelievable. People constantly dismissed it. “Oh, it’s teenage boys in their basement. This is CB radio. This is never going to be mainstream. I’m never going to buy anything on the internet. That’s totally ridiculous. Preposterous.” And so on down the line.

- It was a hard sell. It was not an obvious thing. When you’re doing something where you’re the only, it is very hard to get other people on board. It’s hard to get employees. It’s hard to get investors. It’s hard to get advertisers. You have to do a lot of convincing.

- For 10 years, we kept expecting another competitor to come up but no one ever did. No one could see it.

- We were the only, that’s part of the reason why there were no competitors because we were way ahead in trying to discover things and make mistakes. Not everything worked, that’s part of the thing, but we were the only in many domains.

The Long Arc Of This Force

- You, me, and the smartest 50 people that we knew, we could not make an iPhone, right? From scratch, it just requires so many other technologies, which themselves require other ones. That is a system.

- I call this system, “The technium,” which has all the technologies in the world tied together. We can think of the technium not as something that humans make out of our mind. The birth of it is actually back at the big bang. It’s actually a cosmological force that’s running through the galaxies and the planets and life, and then it’s being celebrated through the technium, and will go beyond us. There’s this long arc of this force.

- What the technium wants is very similar to what evolution wants. It’s headed towards increased complexity, increased diversity, increasing specialization, increasing mutualism, and other things.

- One of my goals is to listen to the technology, to listen to it, watching how people actually use the technology, versus what it was invented for. You can see how outlaws and kids use it.

- We can give it a couple of generations, then we can tell more through the use of it, and the street use of it. There are ways that we can listen to the technology, to try and discern what its biases are.

- I don’t think there is a destination; I think there are directions.

The Underestimated Network Effect Of Giving

- The secret of this world of network communications is that they exhibit network effects in all dimensions. If you can tap into one, it’s wonderful because you can go for quite a ride. All kinds of aspects of our lives are affected like this.

- It’s true not only for ideas. There’s a universal truth buried even deeper that is a network effect of giving: The more you give, the more you get — and the more you get, the more you give, and that’s also a network effect.

- Silicon Valley has institutionalized some aspects of this, where it has emphasized sharing to maybe a greater degree than other cultures have.

- There are a couple of other kinds of classic virtues like gratitude, which is very aligned with humility, and related to luck. Basically, it’s appreciating how lucky we are.

- Luck is a huge component that’s not talked about often enough. If you are really honest about your successes, there’s a huge degree of it that is attributed to luck. I respect the people who acknowledge the luck in their life.

You can listen to the entire podcast conversation here.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.