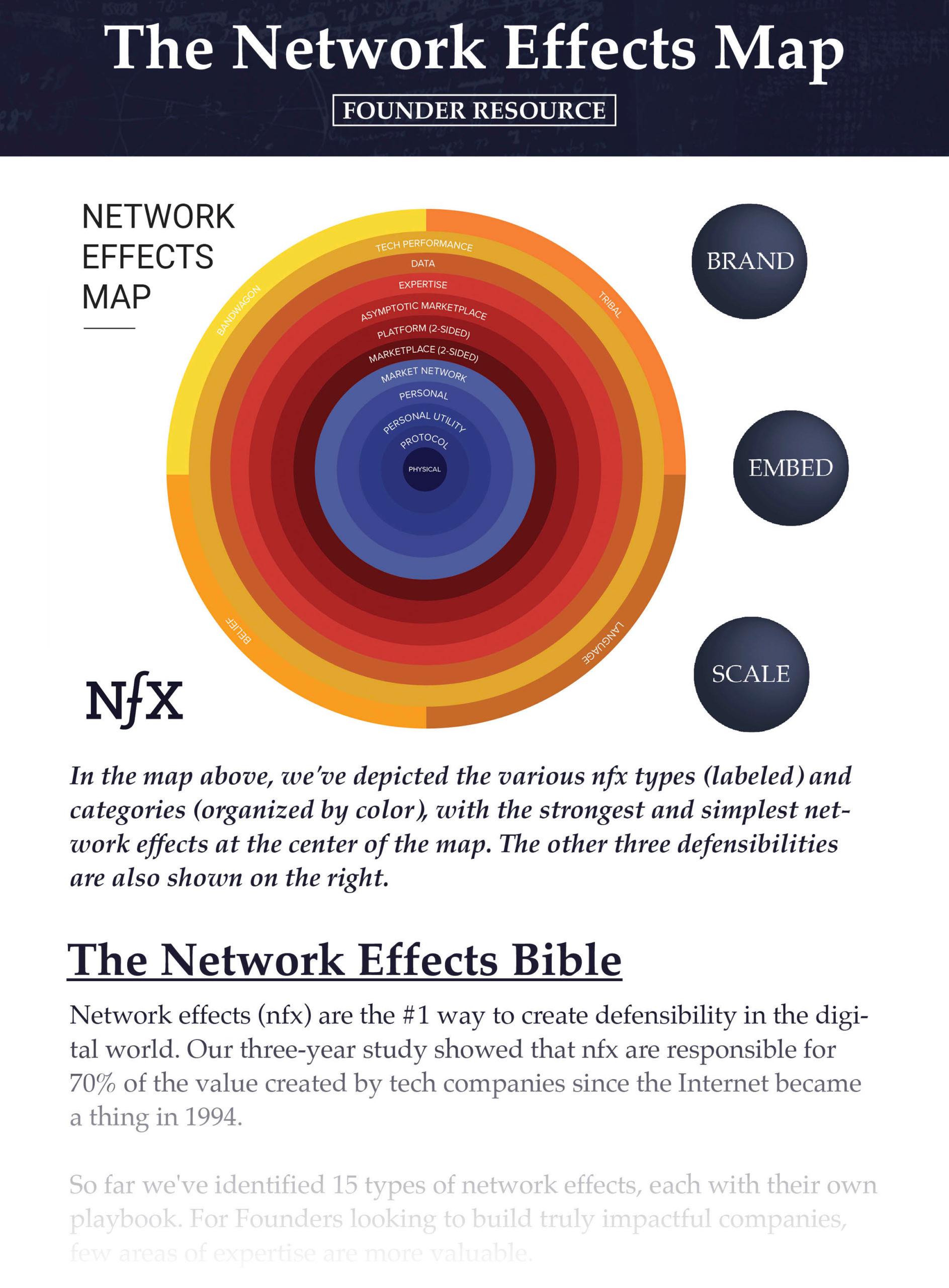

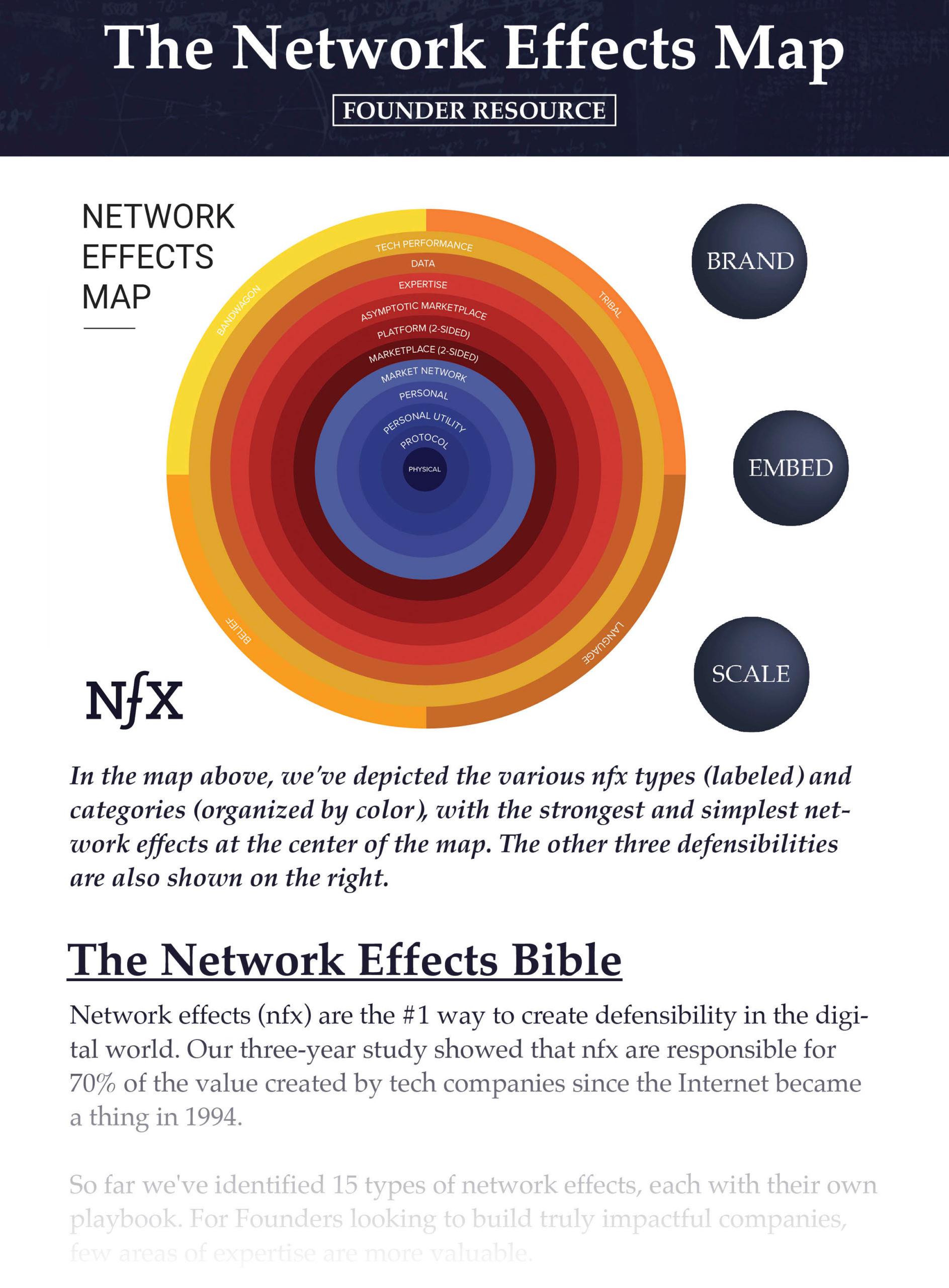

Why do some networks succeed and others fail? One consistent pattern of successful networks is that they have scarcity early on so that people can signal status, and then over time the network moves toward providing more utility. Humans are hard-wired for status games, so product builders would be wise to understand how status & scarcity function.

In today’s NFX podcast and essay with Eugene Wei (former product lead at Amazon, Hulu, Erly, Flipboard, Oculus), we discuss tactics and frameworks early-stage Founders can apply to their products. These lessons also apply to many aspects of running a business and making world-changing organizations, brands, and movements.

We cover:

1. Status Drives Scale

2. Products Are Often More Entertainment-Based Than You Might Think

3. How Products Make You Feel

4. Scarcity Is A Form Of Power

5. The Precarious Nature Of Status

6. Virtual Scarcity = Real Value, Real Status

7. The Underlying Mechanics of Scarcity

8. Scarcity-Based Games

9. Humans Are Wired To Be Very, Very Conscious Of Status

10. Designing Products With Positive Friction

11. When Our Asynchronous Society Starts To Fray

12. Status in the Metaverse

The below outline highlights my conversation with Eugene, excerpted for startup Founders, product designers, and anyone thinking about how the emotional currency of status can be leveraged for good.

1. Status Drives Scale

- Offering a utility to your user base is the most stable sort of long-term competitive advantage that you can have.

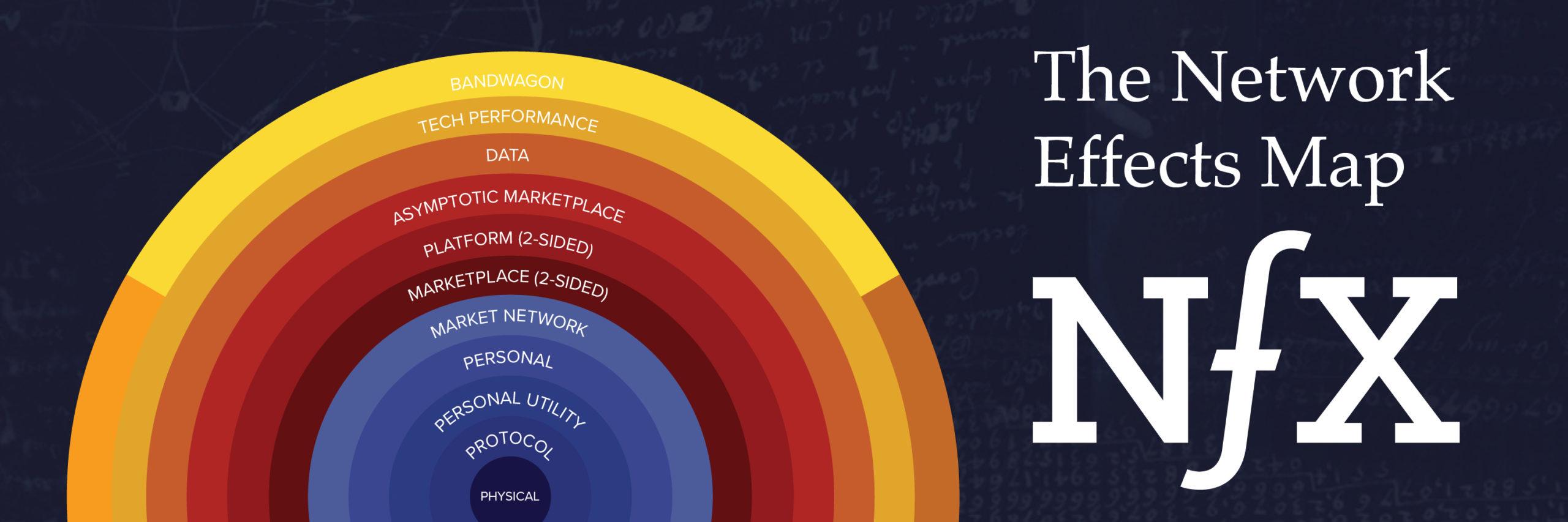

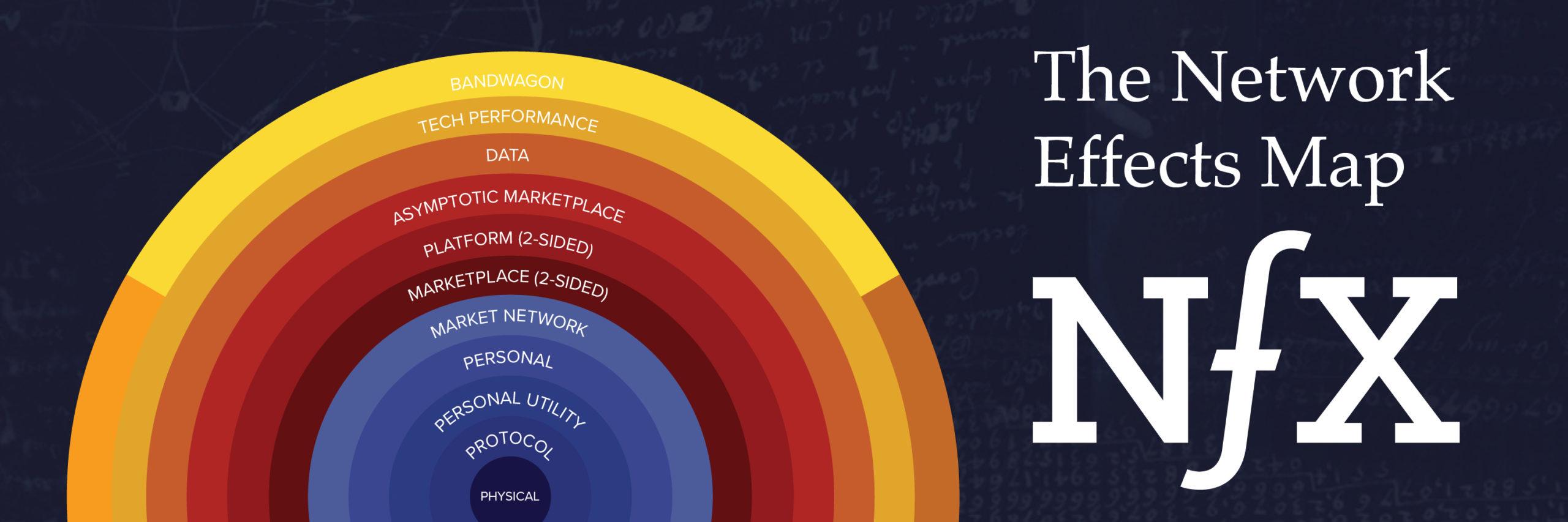

- However, it’s also true that a lot of network-based utility only is realized at some level of scale. (As per NFX: “The simplified definition of network effects is that they occur when a company’s product or service becomes more valuable as usage increases.)

- So the question is, how do you get to that scale? There are a million networks that died out before they ever achieved that scale.

- That’s where status comes in.

- A lot of networks that have achieved super scale had some sort of status incentives or status games built in, very early on. It helped them to get that kinetic energy that you need in order to achieve scale that then increases your utility. Those networks were paying you to develop the network — paying with ego, with status, with a sort of an emotional payback rather than a monetary one.

- I wanted to write about it (in my Status-as-a-Service article) because: I think a lot of Founders come up with their business plans and are always thinking about the utility — about what problem you solve for your end users — but network-based utility requires a very particular sort of path and status is a huge piece.

2. Products Are Often More Entertainment-Based Than You Might Think

The Status-as-a-Service article laid out three axes which are: 1. Status 2. Utility and 3. Entertainment. Eugene wrote at that time: “The entertainment axis adds a whole lot of complexity, which I’ll explain another time.” Much of this podcast conversation covers that third Entertainment axis.

- I’m very fond of the Neil Postman, “Amusing Ourselves To Death” definition of entertainment. The mistake we make is often that we think something is news when it’s actually just entertainment. Postman defines news as something that will change your behavior. So if I told you it was going to rain today and you had to go out and you decided to bring an umbrella, that’s actually news because it changed your behavior. But hearing some story about some political brouhaha or something that happened in the tech world, or some company getting acquired, a lot of that actually won’t change your behavior at all and so it’s just entertainment.

- There’s a broader lesson to learn from that about the products that we offer to the world in tech: Many people think that their products are very utilitarian. But I’d argue that a lot of products that people build are actually entertainment-based products.

- The reason this is important, this distinction, is that I think in the modern world, because of the smartphone being always connected to the Internet, holding a whole bunch of different apps of all different types, we’re seeing a collapse of the barriers that used to separate different forms of entertainment into their own sort of verticals.

- When I was a child, I had an actual geographic separation of different forms of entertainment:

- I’d only watch TV in our family room because that’s where the TV was.

- I’d only play video games in my bedroom because that’s where I had the little Apple computer that I would load games on.

- I would only listen to music really in the car because that’s where we had a cassette tape player and radio.

- And I’d only really watch movies at a movie theater with friends because that’s where movies were played.

- Over the years, those entertainment options have started to blend into each other. The smartphone ultimately collapses all those things into one device. So every time I unlock my phone now I’m given a choice of anything. I can choose what my diet of entertainment is. That actually makes all these forms of entertainment, previously separate, actually absolutely competitive with each other.

- And so you see this now, for example, with sports. The major sports leagues have an aging viewership. Kids today often choose to play video games instead of watching sports on TV. You might say, well, those are two different things. Watching sports is a totally different thing than playing a game with your friends.

- But in that child’s mind, it doesn’t really matter. They’re just choosing how to maximize their entertainment value at that moment in time.

- And so I think a lot of companies that formerly looked at their competitive set as companies that were directly in their vertical are missing out on the fact that they now compete with companies in a variety of verticals.

- Another example: if you’re going to go argue politics with people on Twitter, people think of that as something heavy and serious, but I think that’s just another form of entertainment.

- Social media, ultimately, is mostly just about entertainment, not utility. And that’s just more precarious ground to be on than say, if you were truly a utility-based network. Like if you have a network like Uber or Lyft, I mean, you’re ultimately about getting someone from point A to point B. That’s not really an entertainment-based product. So your competitive set may be more limited.

- So I think it’s very critical if you’re doing a startup to understand if you are going to be offering a product that is actually an entertainment-based product — because that really widens your competitive set.

3. How Products Make You Feel

- As a product person, I’ve become more cognizant of how your product makes people feel.

- I think we’re more used to a very clinical, economics-driven analysis of products. But an understudied and overlooked aspect of product design is that, a lot of times, people use products that just make them feel good.

- People in the gaming world have an intuitive understanding of how important this is — how important it is, moment to moment, to track your user’s emotional valence.

- That’s partially because games are continuous, interactive experiences. The user in a game will churn out it he’s not feeling the right balance of:

- Challenged

- Motivated

- And rewarded

- That same principle can be applied to a lot of other products. How products take off = a lot of it is in how they make you feel.

- If you watch any Apple keynote, going back to the Steve Jobs days, he is underrated for having this very intuitive understanding. Part of why people buy Apple products is that it makes them feel cool or it makes them feel creative.

- That applies to social networks just as much — if not more.

- Many Founders miss out on this because mental frameworks that are more common in business and analysis tend to be more focused on things that are measurable or easily measured, which often is some sort of utility-based function. It is much harder sometimes to measure that emotional quality.

- What emotional payoff does your product have? You may have to actually sit in a focus group and watch the body language of someone to really understand that. But often it’s just in their minds, in their heads.

- And so the downstream metrics that capture that are too late in the game, or we don’t connect them back upstream to a user’s state of mind.

- It’s very hard to convince people of emotional and psychological things where it’s easier to convince them of utility things. This is true within product teams, too.

- If you think about the average cross-functional team working on a product, you have a product person, you maybe have a designer and maybe have an engineer. And there is one model of product development that moves things through that chain in sort of an assembly line type of process. But if you allow any one function to have total veto power over the overall product design, it only takes one person who is only thinking in a utilitarian mindset to maybe torpedo the product’s more emotionally appealing aspects.

- It’s easy to forget that product development in the tech world, in the software world, is actually still a relatively young profession in the scheme of things. Funding and everything into the tech world has flowed in like crazy. People have been flying by the seat of their pants for a long time. We haven’t had time for it all to settle down. We haven’t had time for all that knowledge even to move from some people’s heads into other people’s heads.

4. Scarcity Is A Form Of Power

- I was reading this book Lords of Strategy, which was about the four people who invented business strategy in the ’60s — the founders of Kinsey, Bain and BCG, and then also Michael Porter out of Harvard Business School. There are all these frameworks that they still teach you in business school. A lot of them were built around a world of more defined scarcity, like for product managers at Tide or Clorox.

- Those frameworks are not that helpful in a world of infinity, a world of abundance. If you’re in a tech world where you have winner-take-all dynamics and network effects, where you have things that are absolutely free and infinitely available, well, at the edges of that, the old prescriptions kind of break down.

- Your intuition isn’t going to work if you’re just extrapolating from a world of more constrained supply, a world which doesn’t have as many free substitutes and competitors available.

- But if you’re allowed to define scarcity on any axis, that is a form of power.

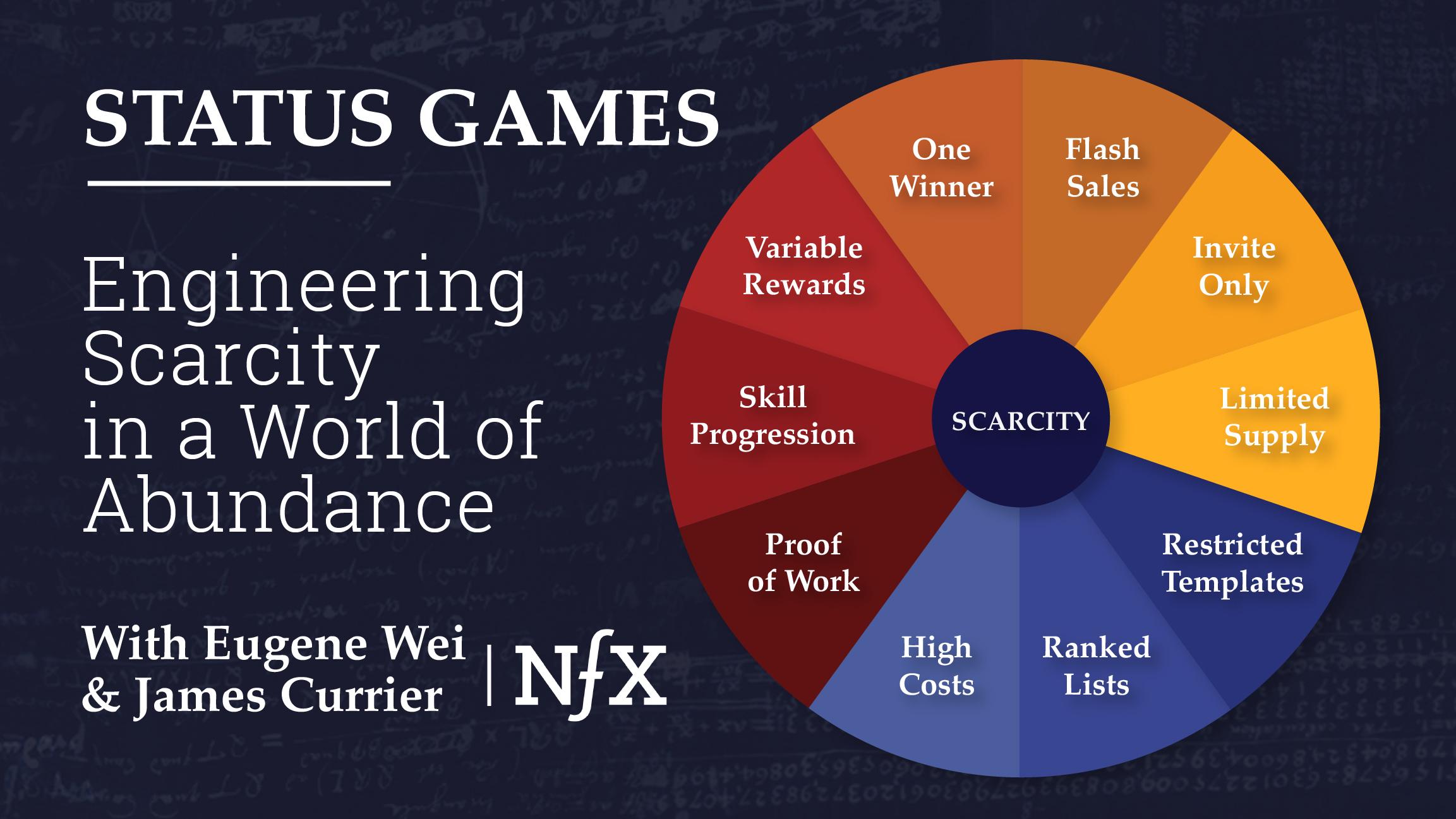

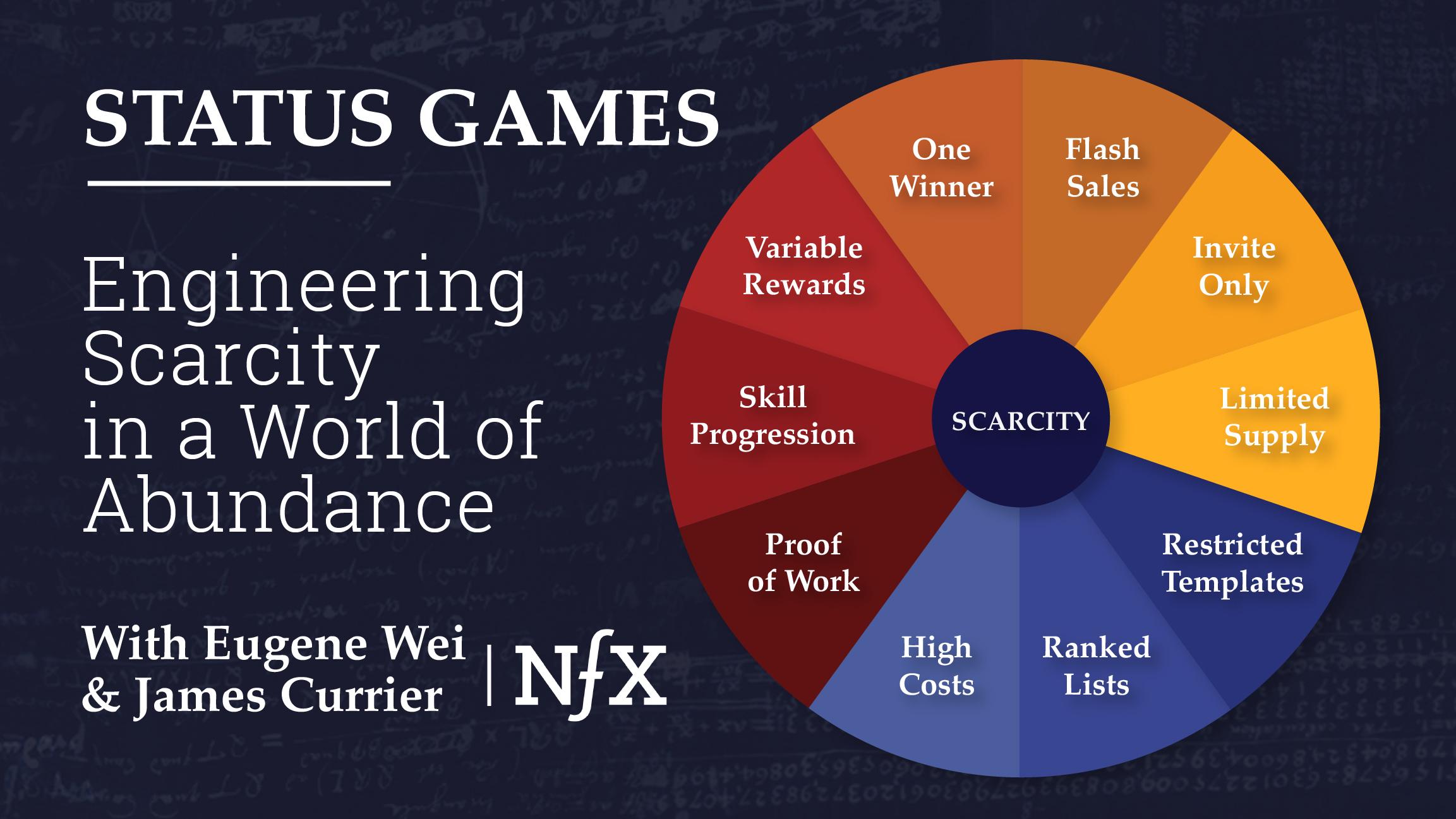

- Video games have become leaders at figuring out how to define forms of scarcity. One example of scarcity in the gaming world is something like a Battle Royale game mechanic which basically boils down to: “There’s going to be one winner out of this group of a hundred people every so often.”

- You can also look in the retail world for similar things where you have flash sales and things like that, where it’s just constrained inventory or limited time for something.

5. The Precarious Nature Of Status

- If we study traditional status mechanisms in society, just generally, it’s always the case that someone is always going to create something even more scarce to differentiate.

- A funny example is: in LA you have these social clubs, like the Soho Club, which are elite. Only now there are actually newer clubs that are even more elite. The San Vicente Bungalows — it’s even harder to be a member than it is for the Soho Club.

- You see this continually recirculating game of tightening up that scarcity.

- When you think about status, one of the important things to understand in the long run is that managing a network and the status dynamics within it evolves over time. It’s the precarious nature of status. We all know that there will be some hot nightclub in New York one year, and then just one day, it will die off and will have to be shuttered and rebranded as something new.

- Status does have a particularly volatile quality where, at scale, at some point, it can just collapse.

- That’s why I always say, in the long run as a network, you want to evolve to some utility-based offering to your customers because if some service offers a utility to you, you’re not going to actually switch, unless you stop wanting them to do that function for you. You’re not going to stop using Uber or Lyft, unless you find another way to get from point A to point B or you don’t need to get from point A to point B anymore.

6. Virtual Scarcity = Real Value, Real Status

- China is a good test case of the new world of scarcity, because I think they leapfrogged ahead on many aspects and live more of a digital native life than many people in the West.

- They’ve gotten really good at all aspects of trying to define some new forms of virtual scarcity.

- A younger generation in the US is actually also very attuned to the emotional value and the status that comes from ownership of virtual goods — whether it’s in video games or elsewhere.

- That’s a very big societal shift because if a centralized provider can guarantee the scarcity of that virtual good, then it actually does have emotional value. People who play League of Legends all know how hard it is to acquire certain types of equipment in that game and there’s a flourishing aftermarket for it.

- I think China leapfrogged ahead of the West a little bit on that, but that type of virtually defined scarcity is going to come to the West.

7. The Underlying Mechanics of Scarcity

- Every product person or entrepreneur moving forward needs to have familiarity with the tactics and strategic understanding of this important point: Structurally, when determining how you build your product, part of what you’re doing is defining what scarcity means on your platform.

- I think some people view this type of thing as purely dystopian, but I don’t necessarily. I think it comes down to how you decide to use scarcity in your products.

- For example, at Amazon, in early Amazon times, we knew that customer reviews were a huge plus to the shopping experience, and we wanted more reviews from our customers. And so we created this ranked list of every reviewer on the entire site. You would have a customer review ranking of something like 12,942. And it was just based on the number of, “Hey, this review was useful,” votes that you accumulated over some time period for your reviews.

- Once we set that up, people went crazy writing reviews. It was especially beneficial for you to write the first review on a product that had no customer reviews. Because anyone looking at that product would have to look at your review.

- Do you remember when Amazon had global sales rank? Every product on the site had a sales rank. Do you remember all the authors competing? They were like, “Please, buy my book. I have to move my sales rank up.” So it was a mechanism that served a purpose at a time in the company’s evolution — and then ultimately got deprecated after it wasn’t valuable anymore.

- It’s all just a made up scarcity. There’s no actual physical constraint time. You are just creating the mechanism.

8. Scarcity-Based Games

- You can think of all of these things as a game. The reason I compare them to an ICO, in my Status as a Service post, is that there is some sort of proof of work. There is some hurdle that you have to do to capture that amount of status. And if you can define some unique form of proof of work, then you may have something that jumpstarts a new game.

- Look at TikTok, which I’ve written about recently, there are interesting new status games or scarcity-based games that are defined by their particular platform. Their algorithm, their “for you” page algorithm, really ends up as the arbiter of who gets distribution on their platform for their videos. They’ve defined a very particular type of video and a type of culture that isn’t easy for certain people to replicate, even if they have status on their networks. It’s true that some people who are famous can go on TikTok and get a lot of followers, but that doesn’t mean that they’re actually very good at creating the types of TikToks that go viral. There are a whole bunch of new influencers created essentially just by TikTok’s algorithm.

- James: I remember when Vine came out and they said you got six seconds — that was a good restriction to give people; a parameter or sort of a blank template in which to pour something. But it wasn’t restrictive enough. Musical.ly came along and said, “No, we actually want you to use music in the background. And we want you to do a little thing, like a little dance or…” And as soon as they put even further restrictions on it, that’s when it really started to work.

- James: We saw the same thing with Fiverr which said, “We’re going to do a marketplace, but everything has to be $5.” And everyone’s like, “What? That’s a stupid idea. That’s ridiculous. Things don’t just only cost $5.” Well, it turns out that it works as a way of starting off, to restrict the template enough so that an initial group of users can get excited about it and then start to build that network effect.

- These restrictions, in order to create the scarcity, drive initial white-hot center type activity, which then can bleed into bigger products.

- The risk is always that you put in some restriction and people go: “Oh, it’s not even worth going through that. I actually don’t care.” And you just end up killing off usage of your product.

- So you have to define some form of restriction where enough people feel a sense of progression. So you need a challenge, but you also need to give people hope that they can overcome that challenge with enough time or enough grinding or enough improvement in their skill level. Otherwise, they just churn out. That’s why they talk about games with a heavy skill cap, being sort of really limited in their TAM or the ultimate user base. Games like chess have a really high skill cap.

- In the early days of Instagram, there was a sense of progression in that they had filters and things that allowed you to feel like you were improving as a photographer. But the part of Instagram that’s challenging now, is a lot of that network is about if you have a lot of wealth or something, and the average person is going to be like, “That’s not my life. I can’t compete with that.” And so there is a point in which you start to feel you could churn out of that network because you’re not going to feel any progression.

- The difficulty in all of these things is that the status dynamics are constantly shifting as more people join. Just like managing a game like World of Warcraft over many generations. There were certain versions in the early days, where they got stuck because a new player just had no chance to compete with an experienced player that had progressed much further in the game because they just had so much more equipment or power. And it was just overwhelming. So then player matching and skill matching became a huge and important art in the game world.

- I think it’s the same with social networks like Facebook and Instagram, everything. At the level of scale that they’re at now, the status game and the sense of progression is going to be way different than it was when they were just starting out.

9. Humans Are Wired To Be Very, Very Conscious Of Status

- James: There’s this great book, Impro by Keith Johnstone. He became one of the greatest improv teachers in the world, based on this one insight: If you make status the key driver of how people act on stage, suddenly everything becomes clear. Everything becomes real and your actors are that much more engaging to the audience because they intuitively understand how every sentence, every movement displays some sort of status relationship between people.

- There’s something to the idea that humans are wired to be very, very conscious of status. It may have come from another time in mankind’s history when your status within your small tribe or group was actually critical to your survival.

- That carried over to the modern world — and the fact that we have these social networks that knit together the world, that allow us to see the activity or status of other people all over the world has sort of, I think, risen the stakes.

- These social networks have pushed the emotional stakes of status games to, maybe, an unhealthy place.

- There’s this older book called Class by Paul Fussell, which is about status in American society. He talks about how backsliding in status is one of the greatest fears for any person in society. You never want to be seen as middle-class and then backsliding out of the middle-class, or you don’t want to be in the upper-class and then backsliding back into the middle-class. People have deep anxiety about that.

- I think there’s a degree of this in our general sort of economic inequality question in America right now. Where people talk about, “Hey, we’re starting to see class mobility sort of stagnate.” It’s like a game where progression has stopped for a huge segment of society.

- Anytime a person feels like someone else might diminish their status or lower their status — and we know status is a relative measure — every sort of emotional defense will fire. And that’s one of the most threatening situations people can be in.

- A lot of political debate on social networks can model as ‘team versus team’ games, where everybody thinks of it as zero-sum: “If that person gained status, then I have lost status in some way.” And we know that anytime a game is viewed as zero-sum, it becomes much more vicious.

- In a more positive-sum environment, if the GDP growth were higher and everything, I think that sort of just eases the tension throughout the system.

- But anytime you create a more directly competitive situation — we know this from game design perspectives — then it becomes an adversarial game. If you descend into a zero-sum design of status, you almost can’t avoid ending up in this really vicious negative cycle.

10. Designing Products With Positive Friction

- I don’t know if our current social networks will be the ones to solve these problems. I’m not sure if the negative side effects will rise quickly enough to cause them to be the ones to adjust their own behavior.

- But I certainly think some new social networks might come along, study the ones that are at super scale now, and learn from their mistakes.

- A lot of it comes down to how you think about friction in your product. So much of product design in gen Y and Silicon Valley has coached us to “remove friction, increase virality, increase engagement, increase network effects, regardless of what form that engagement takes.”

- All product people have had it beaten into their heads that, “Hey, you’ve got to remove friction from every process in your app. From the signup flow to this flow, everything has to be fast and easy.” Not necessarily…

- All these networks are hardwired to act like a rail gun. It’s just about accelerating things that show any form of engagement. We have to start distinguishing, at the product design level, between positive and negative forms of engagement.

- I would argue that a lot of news that travels on Twitter today, the most provocative, controversial, crazy disinformation, a lot of that problem could be solved if we applied more friction to the distribution of that stuff.

- You actually need a proof of work. You do need some friction in the product, and it can be used for something good. It can be used to motivate.

- When we think about product design, we have to think about those positive forms of friction.

11. When Our Asynchronous Society Starts To Fray

- In the first decade or two of the web and the smartphone, everything was really focused on efficiencies achieved from going asynchronous.

- “Hey, why do I have to watch Friends at 7:00 PM on a Thursday?” Netflix responds: “You can just watch things whenever is convenient for you.”

- With messaging, we used to have to call people and hard-interrupt them to communicate with them. And then we got email and messaging and it was like, “You know what? Most things aren’t that urgent. Let’s go asynchronous in our communications.”

- People generally thought: “Wow, this is a great advance for the world.”

- In every field, you can see there are huge gains to going asynchronous.

- But I also think we’ve lost that social feeling of community that comes from synchronicity.

- Over time I believe we will once again say: “It actually does matter occasionally that a society is all watching something at the same time, or that you and a group of people benefit by doing something together.”

- That’s not to say that all the gains from going to remote work and asynchronous processes will go away — it’s more that we underrate how much we feel connected to other people when we synchronously do something with them.

- A lot of our social fabric, our feeling of: “Hey, we’re all Americans in this together” or something comes from a bunch of synchronous processes and rituals, like going to church or whatever it is. These are starting to fray over time. That’s then when you start to feel like societies start to fracture when you don’t have that feeling of communal harmony.

12. Status in the Metaverse

- We have long held this idea that there will someday be this kind of Metaverse-like world that more of us live in. We actually have already partially transitioned into it with our smartphones. I mean, yes, we’re not necessarily wearing VR headsets and spending all our days like those people in Wall-E. But most people I know today spend a good fraction of the day with their faces in their phones, interacting in software-constructed environments. The fact that it’s not 3D, I think that doesn’t matter — it’s still a form of sort of low-fidelity Metaverse.

- I think we’ll get another turn of the Metaverse, this sort of lower-fidelity Metaverse, before we get the actual, real, Ready Player One style Metaverse.

- The pandemic has sped it up. It’s a race. It’s a race to get to building out this entire set of infrastructure for the next turn at a Metaverse-light.

- We’re probably going to get another kind of Second Life at some point that people will actually spend more time in.

- We still have a long way to go in building out what I think of as a real-time ambient presence indicator. In a way, I feel like we backslid from the days when we had AOL instant messenger and ICQ or whatever. When we would just leave the client open 24/7 and you could just alter your status from time to time.

- Essentially, Discord does a version of that for gamers. If I turn on Discord, I can see what games a friend of mine might be playing at that moment.

- But what’s the version of that for everything and everyone?

Listen to the full Status Games podcast episode here and subscribe to the NFX podcast.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.