Many academics never realize that they would make great scientist-Founders. They follow the path that academia paves for them: Ph.D. to postdoc to professorship (if you’re lucky) or working in industry. That’s a shame.

My journey from scientist to Founder to investor didn’t happen in the classroom. I became a scientist-Founder when I saw one of my postdoc colleagues start his own company, and thought: if he can do it, so can I. And, years after I started my first company, Genome Compiler, I realized that I had learned far more listening to podcasts during my car commutes than I had while pipetting in the lab.

Very few academics will actually sit down with you and help you seriously consider the startup option. Fortunately, there are plenty of people out there who have made the leap from academia to startup successfully. Two of whom are Jennifer Dionne, the Founder of Pumpkinseed and Stanford professor, and Yaniv Erlich, the Founder of Eleven Therapeutics and former Columbia professor. In a recent conversation with both of them, we found patterns and key takeaways from each of our academia-to-Founder journeys.

In this essay, we’ll walk through three guiding questions to consider as you decide what path to take:

What kind of freedom do you want?

How fast do you want to move?

Who do you want to be your “customer?”

From there, we’ll cover the classic “Should I do a postdoc?” question, and also help you understand if you have the right ingredients to spin your research into a company.

Let’s dive in.

What Kind Of Freedom Do You Want?

There’s a popular concept called “academic freedom.” The idea is you get to research what you want, when you want, and pursue whatever basic science interests you.

But there is less freedom in this than you might think.

There’s a caricature that captures the true state of academic freedom well. It starts like this:

Imagine that you’re a young scientist. You get to university and think: “I will finally research what I want.”

Then, you realize that you have to get a spot in a lab. So you tweak your inner mindset to: “I’ll study whatever my professor wants.” It’s a small change, but it leads to bigger concessions over time.

Then let’s say you stick it out and become a PI. You think: “now I’ll get to research what I want.”

But then reality hits: You have to research whatever might help you get grant funding and tenure.

You persevere anyway. You become a professor with tenure who can’t be fired. Finally, you get to research what you want.

And then you die.

As I said, this is clearly an exaggeration. But the point is that grant funding, tenure, academic pressure to publish… these are all forces that will limit that so-called “academic freedom.” These forces dictate your academic life far more than people like to believe. Why? Because academic institutions are powerful networks: they will shape your life in both positive and frustrating ways.

My NFX partner James Currier has written about this in detail outside of the academic world: networks push us along certain paths. Academia is no different: what you study, what you find interesting, what you think is truly applicable, what indications you see as worth pursuing, are all going to be shaped by the people and institutions around you.

What Does Freedom Look Like For Scientist-Founders?

When you start a company, you will still be learning and experimenting, but all of that learning will be in service of one ultimate goal: create a great platform or product in order to solve a problem in the real world.

You get to choose what the problem is. If you want to pursue the programming of RNA you get to pursue that. If you want to make glowing plants using synthetic biology techniques for consumers you can do that too. If you want to build a billion-dollar company around previously undiscovered CRISPR systems – go do it. You make your own rules. But you don’t get to “learn for learning’s sake.”

Every step you make will have to be in the service of the product you are making. You will experiment and iterate, but you will need to be smart about why and how you choose to do it.

That said, you will be free from institutional red tape. You can create your own lab environment where you get to set the culture, HR standards, the salaries, the goals and the pace.

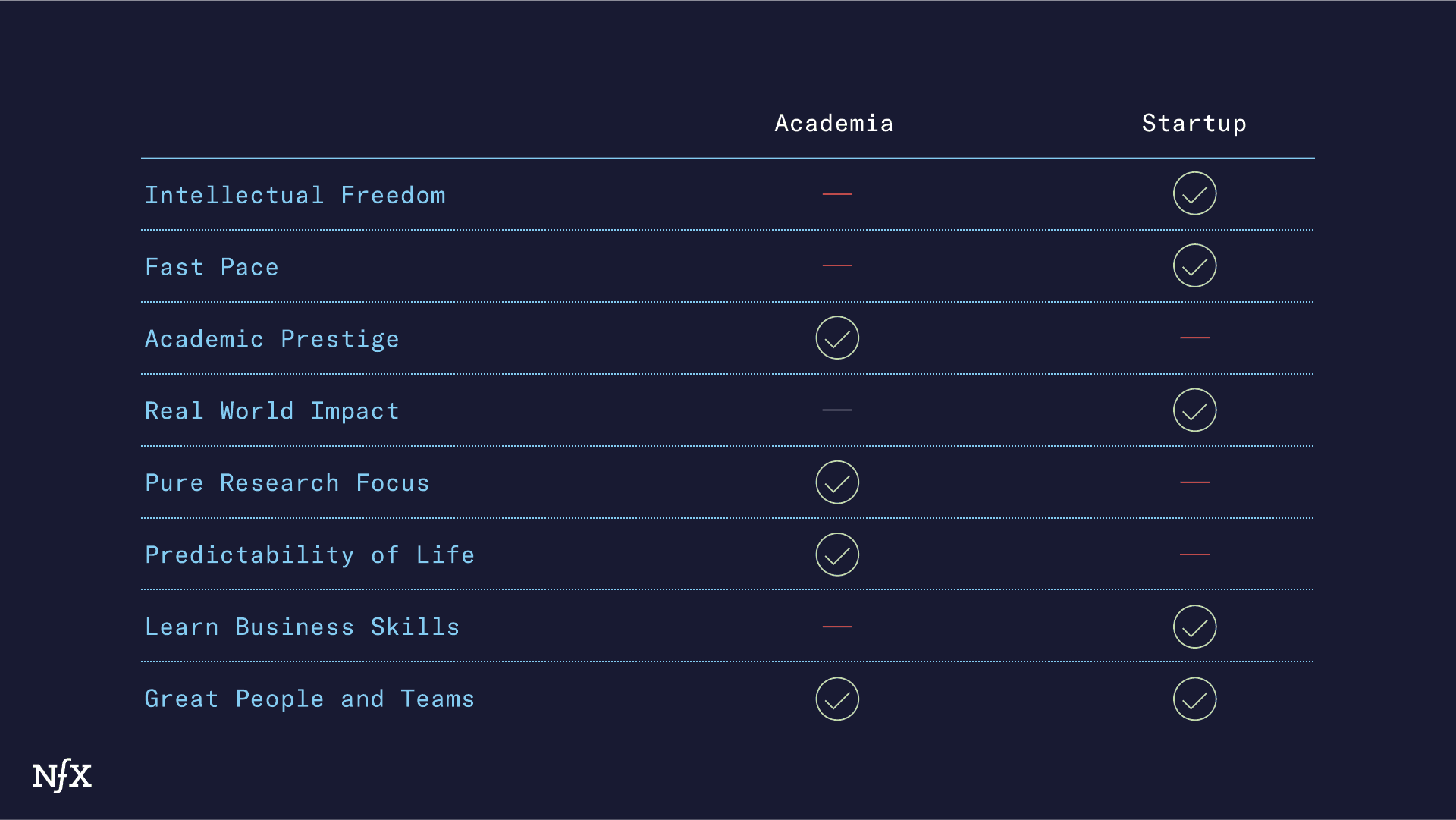

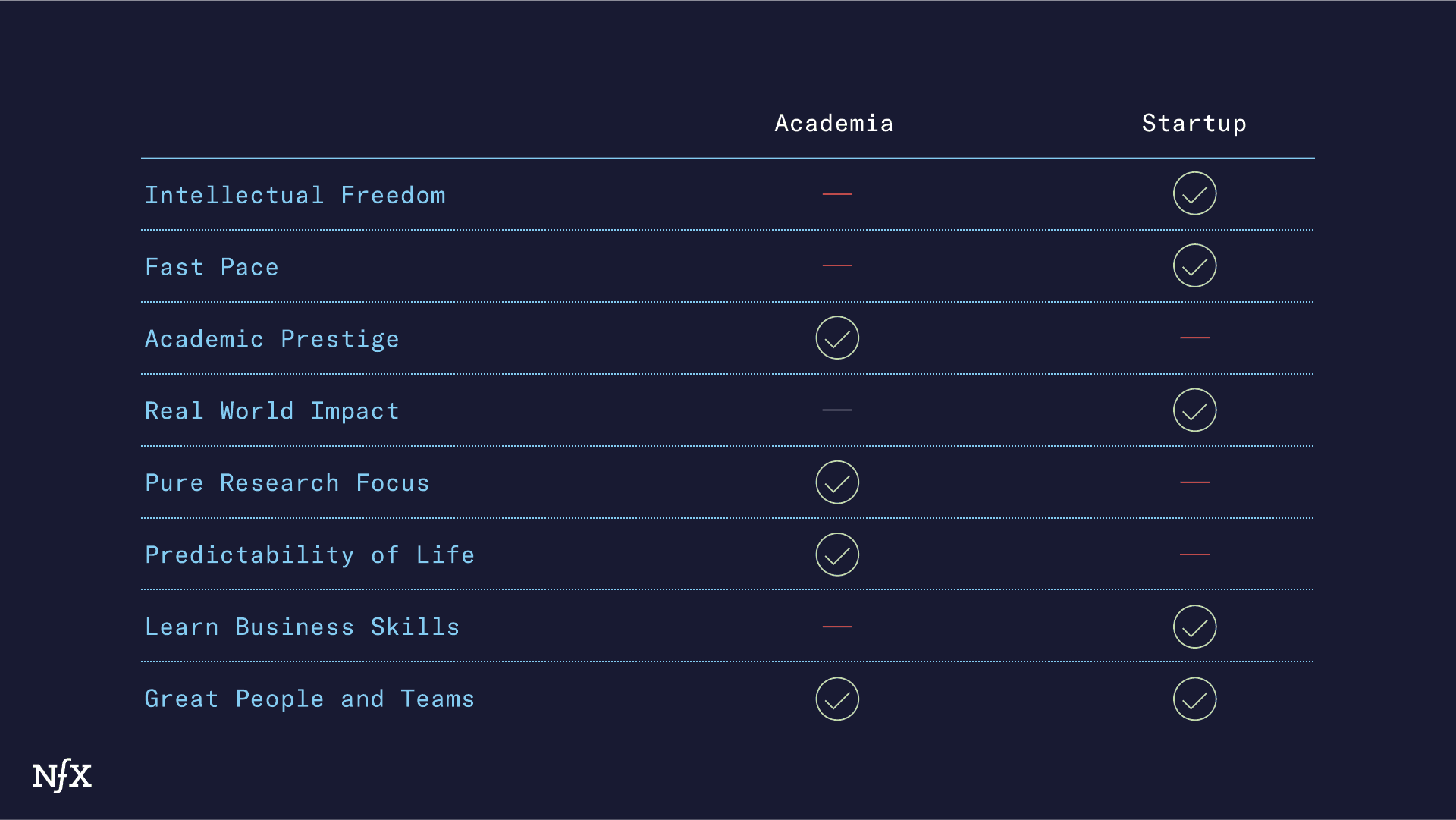

In short, you gain operational freedom, but you lose the ability to experiment without a care for the eventual application. This tradeoff between curiosity-driven research (usually seen in academia) and outcome-driven (usually seen in industry) has been the status quo for decades.

We are starting to see some academic labs harness the best of both, which is great. Jennifer Doudna’s lab at UC Berkeley has spun out numerous startups including the unicorn Mammoth Biosciences.

If you can find one of those entrepreneurial labs, great! These labs are engaged in frontier research, and have also built a culture where it’s acceptable (if not encouraged) to take that IP and do your own thing. That’s a terrific place to be as a young scientist, especially if you think that you may want to become a scientist-Founder.

How Fast Do You Want To Move?

Everyone knows that a startup moves faster than academia. But this discrepancy is getting bigger every year. You need to think carefully about how you want to measure progress in your life when you weigh the startup versus academia paths.

In a pre-internet, pre-TechBio world, the fastest way to bring your science out of the lab and into the world was to publish it in a pen-and-ink journal that only your peers would read. Then, months or years later someone might expand your work.

Today, despite exponential digital revolution, we know that the speed of academic publishing is incredibly slow compared to the pace of innovation. TechBio has allowed us to put science into practice immediately. You can build a machine learning model and test multiple hypotheses at once. You can build a platform that continuously learns.

We’re not saying that you shouldn’t publish in well-respected journals – you should. But the idea that this is the best and fastest way to make sure that your work makes an impact on the world is old-school thinking.

If you want to see your work make a difference in the world, think about whether publishing a paper and hoping for the best is enough for you.

That’s one way to look at speed. But you also need to consider speed from a personal perspective. What rate of change do you want to see in your own life over a certain period?

A year is nothing in an academic context. A year in the startup world is an eternity. In that time you could have built a company from the ground up, changed your entire life, and impacted many more.

You have to decide what units you want to measure your life’s progress in. Do you want a year to feel like a drop in the bucket, or jam-packed with the ups and downs of making things happen?

Who Is Your Customer?

You aren’t the only person who derives value from your career. One way to think about the startup versus academia path is to consider who else might benefit from your life’s work.

In academia, who is your end user? If you’re a good professor, it should be your students. That means you should be pouring the most effort into helping them further their careers and education.

When you start your own company, you are creating value for your end user. That could be a person, a patient, a company – remember, you make the rules. They are best served by making the best product or platform you can, so you will pour all your resources into that product.

Think about which customer motivates you the most. Will you feel more rewarded when a patient uses your new platform, or when your student completes their Ph.D. under your guidance? These are both very fulfilling life missions, but you may be drawn to one more than the other.

Is A Postdoc Worth it?

The first place where the academia versus startup tension becomes visible is when you decide whether to pursue a postdoc. It’s a crossroads moment.

The easy answer is to do the postdoc. In many academic circles, it’s presented as the natural next step. But it is not a requirement to have a great scientific career – though some may try to convince you it is necessary. The biggest mistake you can make is to just do a postdoc out of insecurity or lack of confidence. If you really are unsure, broaden your horizons, travel if you can, apply to jobs, or ask your PI if you can stick around for a bit longer.

In 2019 Yaniv Erlich, the Founder of Eleven Therapeutics, wrote a compelling tweet thread prompting PhD students to rethink the postdoc model. Instead of thinking of a postdoc as the next academic step, think of it like a job – consider salary, and what stage of life you are in right now.

Yaniv has described how this situation can play out when people assume that a postdoc is right for their specific life situation:

“We [Israelis] usually get married earlier than the U.S. population, so they are married [during a postdoc]. They have kids, maybe one child already, and then they take their family abroad. They don’t understand that the salary that they will get will probably be very close to the poverty line if not below the poverty line.”

The postdoc path also requires sacrifices. The best professors will tell you that a postdoc is an option, but usually not a requirement . That’s the advice that Jennifer Dionne, Pumpkinseed Founder, has given to her students at Stanford:

“When I’ve had students who have wanted to go into a postdoc, I’ve encouraged them to think about what they want to learn and what their learning goals are before they start their independent careers.

If they feel they have the technological foundations from their PhD to either go off into industry or to start their own company, and they already have a pretty solid foundational toolkit to be successful in what they want for their career… then I don’t think it’s worth going to do a postdoc.”

That’s not to say that starting your own company doesn’t require similar sacrifices. It’s a huge undertaking that will also put pressure on you and your family.

The point is: If you are going to make those sacrifices, do it because you are working toward an outcome that is truly meaningful to you. Not because it’s a box you feel you have to check.

Once you set yourself on a path, inertia will often keep pulling you along it. Make sure you want to be on that path in the first place.

You’ve Decided To Be A Scientist-Founder. What’s Next?

The hardest thing to do is to just decide. It takes time to overcome that “imagination barrier” especially for scientists who have been raised in academia. But once you have conviction that you can turn your own invention into a company, then this is what you can do.

Start to think critically about your idea, who you want to surround yourself with, and how to spin out of your university. Here are 4 guiding questions to test on yourself.

1. Do you have defensible magic in the lab?

Have you found something no one else can replicate? Or, is your concept flexible enough to tackle a variety of indications? (If you’re curious about what TechBio platforms really look like, you can read our thesis statement here).

You know you have defensible magic if your concept is truly groundbreaking in your field. After years of academic study, you’ll know what that feels like. Think about the discovery of CRISPR back in the day – everyone from students to tenured professors immediately saw how meaningful CRISPR would be. Those students could have been the Founders of the first generation of CRISPR companies (and some were). But many more people let the moment pass them by.

If you don’t have defensible magic, you can go out and find it. Use your university network. Talk to your peers, find out what’s going on in other labs. There is way more IP floating around in labs that there are people willing to become Founders. Make it your job to find that magic.

2. What stage is your technology at?

When you decide to start a company, you want to be more on the development side and less on the research side of the typical R&D equation. Research can take a week, or it can take forever. We recommend that people start companies once the basic science is validated.

You don’t need to have a product yet. You don’t need to have won a Nobel Prize. But you do need to know that your core science is there. For example, Mammoth started spinning off its CRISPR diagnostics business after publishing a journal article showing that this was even possible.

If you think you will be spending more time developing the science than you are researching the science, you are in a good position.

3. How big is your market?

Many problems that TechBio can solve in the world are existential. Climate change. Disease. Hunger. Sustainable Materials. These are big markets: but you have to better understand just how big your technology can be within those spaces.

Can your defensible magic tackle many problems at once? Or just one? Just one is okay, but understand if that one problem is big enough to build an entire company around.

4. Do you have the right team? Or can you find the right team?

Many new scientist-Founders overestimate how hard it is to learn entrepreneurship. This is something you can learn to do yourself. But it is easier to do this with the right team.

You can fill gaps in your own knowledge by selecting people who come from different backgrounds. Walk over to the business school at your university and see who you can connect with.

A Crossroads Moment

At NFX Bio, we are seeing more and more scientists as they investigate the startup route. But this is still very new behavior, and there are still too few scientist-Founders in the world.

We want scientists to realize that starting your own company is an equally viable life path compared to academia. Don’t think about it as “leaving something behind.” Think about it as starting something new – ripping a hole in the universe. You gain a new and also quite prestigious identity: the Scientist-Founder.

This path is a better fit for more scientists than you might think. Maybe you are one of them. Or maybe you know a colleague on the verge of something big. If so, send this to them. Even that small gesture could lead to their first step in a new, and very exciting, direction.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.