“I have been lucky enough to have him as my tutor. I’ve learned so much from him, and I’m not the only one. He’s been an incredible teacher to all of us.”

– Jeff Bezos, Founder & CEO at Amazon

He built Amazon alongside Jeff Bezos for 22 years. Now he is analyzing the operations playbooks and early decisions that made Amazon so powerful.

For the Founder community, there is no one better than my friend Jeff Wilke (former CEO, Amazon’s Worldwide Consumer Business) to shed light on a counter-intuitive driver behind unusual success: Focus on the inputs, not the outputs.

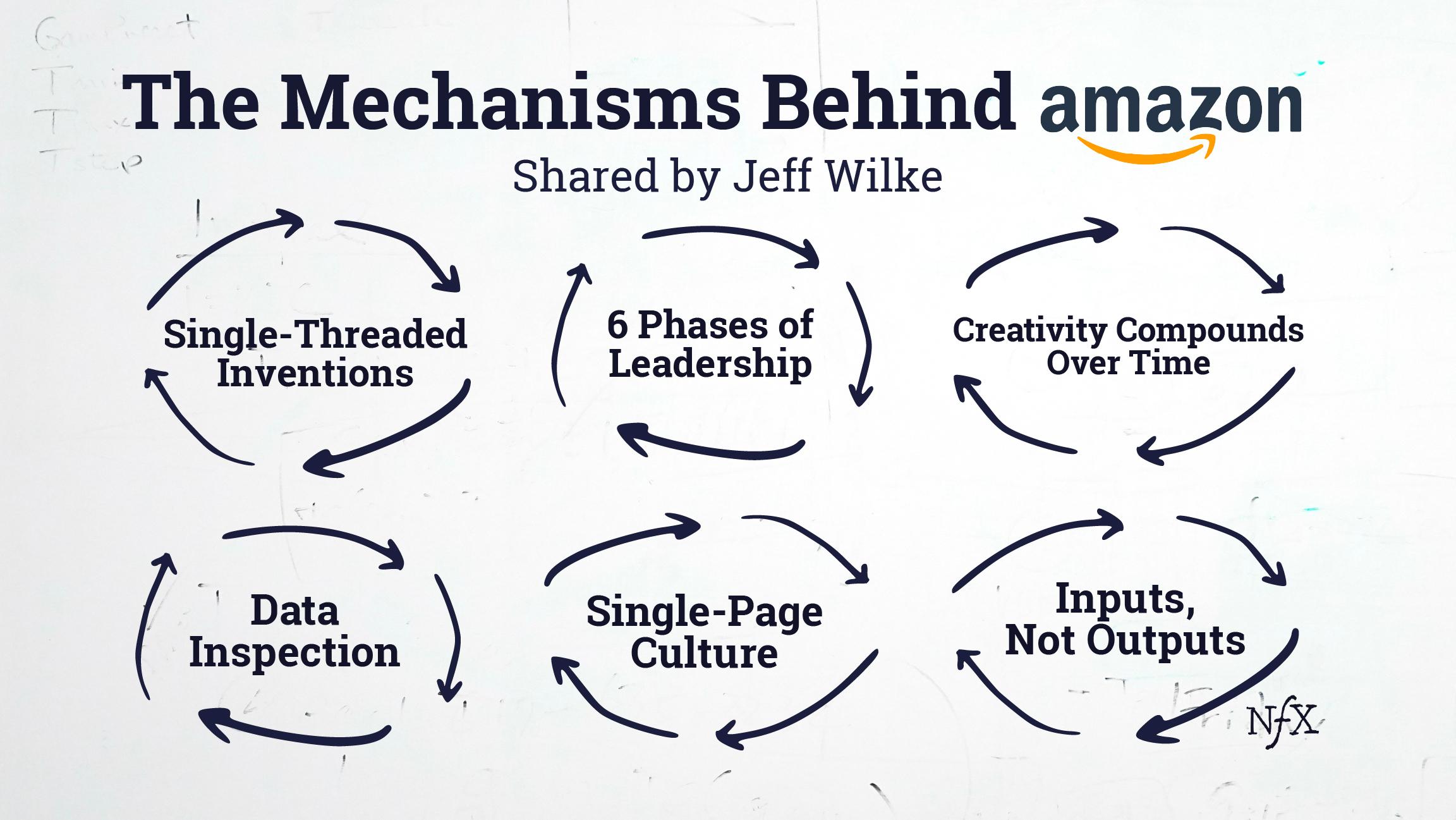

Jeff shares the 3 drivers underlying the rise of Amazon, Prime, Alexa, and AWS, including:

- “Mechanisms”: Amazon’s definition, two failure modes, and why they’re harder to implement than it first appears

- A Single-Page Culture: How Amazon’s set of principles proved to be an inoculation against a drifting culture

- Single-Threaded Invention: How to protect your nascent business lines from the mothership

Most people think product innovation and growth are what drive $Trillion+ outcomes. In practice, operational excellence is the key driver to executing consistently for the long term. This is how you harness creativity that compounds value over time.

When Amazon Called in 1999

James: So we’re in the late ‘90s and your friend is working at Amazon. He’s loving Amazon, and he loves you, so he brings you in and says, “If we don’t hire you, we’re screwed. We’ve got to hire you. Come out and visit us.”

- Jeff: Exactly. For whatever reason, I was in a moment where I was willing to listen. He detected this, so he said, “Why don’t you meet this guy, Joe Galli?” (Joe was our President for about a year at Amazon). “Why don’t you meet Joe at the hotel near Dulles?”

- So I walked into this airport and had a four-hour lunch with Joe Galli; we didn’t even eat anything.

- Joe’s a super passionate guy. He talked a lot about Amazon. And he’s from Pittsburgh, probably two miles from where I grew up. We talked a lot about Pittsburgh, and about the kinds of people that we knew growing up, and what we learned about leadership from those experiences.

- At the end of the conversation, he said: You’ve got to come out and meet the team.

- Uncharacteristically for me at the time, I said “yes” on the spot. I called my wife from the car and said I have to do this. We had just bought a new house in New Jersey and we had a one year old and a three year old. We were planning to raise our kids in this neighborhood. To her credit she said, “I’m not happy about this, but I’ll support you if you think it’s the right thing.”

- And so, two days later, I flew out to Seattle, I met Jeff Bezos and Joy Covey, David Risher, and eventually Rick Dalzell. I was just super impressed with the whole leadership team.

Strategy + Operations Together

- On the way out to Seattle, I read Jeff’s shareholder letter from 1997, the very first one he wrote.

- For me, it struck a chord because I got some sense that despite being words that I’d heard others profess in business, that somehow this company meant it:

- They were going to optimize for the long run, not for quarterly profits.

- They were going to focus on cash, not non-cash earnings.

- They were going to put customers first and try to build Earth’s most customer-centric company

- And innovation was going to matter

- I just believed it. Then I met them, and I believed it more.

- All around me in the world, I was seeing evidence that businesses were sub-optimizing because they were trying to hit these quarterly numbers.

- Remember, this was 1999. It was right at the height of “you can’t have a miss or your career as a CEO might be done.” This feeling that you can’t miss your quarter, everything’s tied to that.

- As a result, I think a lot of people under-invested heavily in opportunities that were available to them. It seemed like Amazon wasn’t going to do that.

- They made an offer before I left that day.

- One of the things I did in the interview with Jeff was ask him to not think of me “just” as the operations person but to include me as a strategic partner in building this company — and he was true to that. Operations and strategy.

- I ran ops for seven years, and then I took over the retail team in North America in 2007. I couldn’t have asked for a better 20 years, friends, leadership, experiences all over the world. It was really remarkable.

On Writing Amazon’s Leadership Principles

- The S-team is the senior team at Amazon. It started out as the direct reports to Jeff Bezos. The longest-serving members of the S-team when I departed Amazon in February 2021 were Jeff and me.

- It was what you’d imagine in the early days: the operating committee or team that ran the company. The early S-team was the Head of Tech, Head of HR, Head of Legal, Head of Ops, and Head of Retail.

- When you go into the mid-2000s, we started to invest heavily in AWS and in the devices business.

- When we got to a more diversified set of businesses, the role of the S-team started to change. It was less about operating the individual businesses and more about deciding on the mechanisms for the business.

- We talked about what we should be doing together to make sure that this culture thrives, that we stay day one versus day two, meaning that it feels like a startup, even if it’s big, and that we continue to attract and retain the very best people in the world.

- We did things together like build Amazon’s Leadership Principles. I was really adamant that we should have a single set of principles that define what it means to be a leader at Amazon.

- We talked about the definition of a leader, and if this set of principles should be only for people who have direct reports, or should they be for every Amazonian? We decided they really should be for every employee of the company.

- I worked with Rick Dalzell, who was our CTO, to write the Leadership Principles — mostly because I think we were the most passionate members of the S-team about this.

- We thought it was important to codify what made this place special — and there’s a lot of Jeff Bezos in the language.

- The leadership principles start with customer obsession and end with delivering results. They’re public, so anybody can take a look at them.

- The first draft clearly wasn’t good enough, and I think Jeff was right to push back on a bunch of things. And through that iteration, we ended up with a set of principles that have been pretty enduring.

- We made maybe two or three other changes in the 18-year life, including adding “learn and be curious” a few years ago. But they really did stand the test of time. Having a set of principles proved to be an inoculation against a drifting culture.

- The S-team was the steward of the leadership principles, first and foremost.

A Culture of Single-Page Communication

- I think one of the things we did right was we use the words in the leadership principles, everywhere.

- We use them when we communicate with each other; we use them when we write documents. And Amazon is a writing culture. Meetings start in silence as you read the document. We don’t use PowerPoint.

- These Leadership words were pervasive. They inform how you give feedback to people; they inform how you set your goals and how you measure against those goals. They inform how we talk to the investment community and customers.

- One of the tricks that I was lucky enough to keep persistently in our focus was not letting the words get diluted with more explanation.

- If the leadership team has done their work well, crafting a single page of principles and values, you could argue that those words are the only words that a new person needs to understand the culture.

- If you end up having the urge to create Wiki pages to define and further elaborate on each of the principles, you may not have written them crisply enough to start with.

- At Amazon, when you’re teaching somebody the leadership principles, you have to go to the primary document, have the person read it, and think deeply about it.

- Then ask them, what do these mean to you? How do you think you’d employ them in your work?

- Human cultures and businesses create cultures, the oral tradition matters a lot. Spoken word is very powerful.

- I think we sometimes fool ourselves into thinking that the artifacts that we create that are in PowerPoint or in prose or in binders sitting on a shelf really define the models people have of the company and the way people interact.

- There’s the way you wish it was, and then there’s the way it is. And if you can get those to be as close to each other as possible, you’re going to succeed.

“Uninspected data is always wrong”

- People use mechanisms as substitutes for process all the time, or even as a synonym. At Amazon, a mechanism is a tool or a process where you achieve adoption. So you actually do the work to make sure that people understand the tool or process.

- But, most importantly, you periodically inspect to make sure that the tool or process is being used as intended — and if it can be improved.

- If you find that it can be improved, then you improve it, you get adoption for the new version, and so on.

- It seems simple but what I find over the course of decades is that most tools or processes that companies implement eventually go off the rails with these 2 failure modes:

- You go back to something 10 years later and people are still doing it even though the reason to do it is long gone.

- What may be worse, or maybe just a different failure mode, is you go back and there’s a real need for the process, but it has mutated into something that adds no real value. However, again, people are doing it very diligently.

- You can’t blame the people whose job it is to do the process. You actually have to inspect the process and ask, is this optimal? Is it working? Is the data still as accurate as I thought it was?

- We would always say uninspected data is always wrong. This obsession with the inspecting process really led to some of the operational excellence that was vital for things like Prime.

“Creativity that compounds value over time”

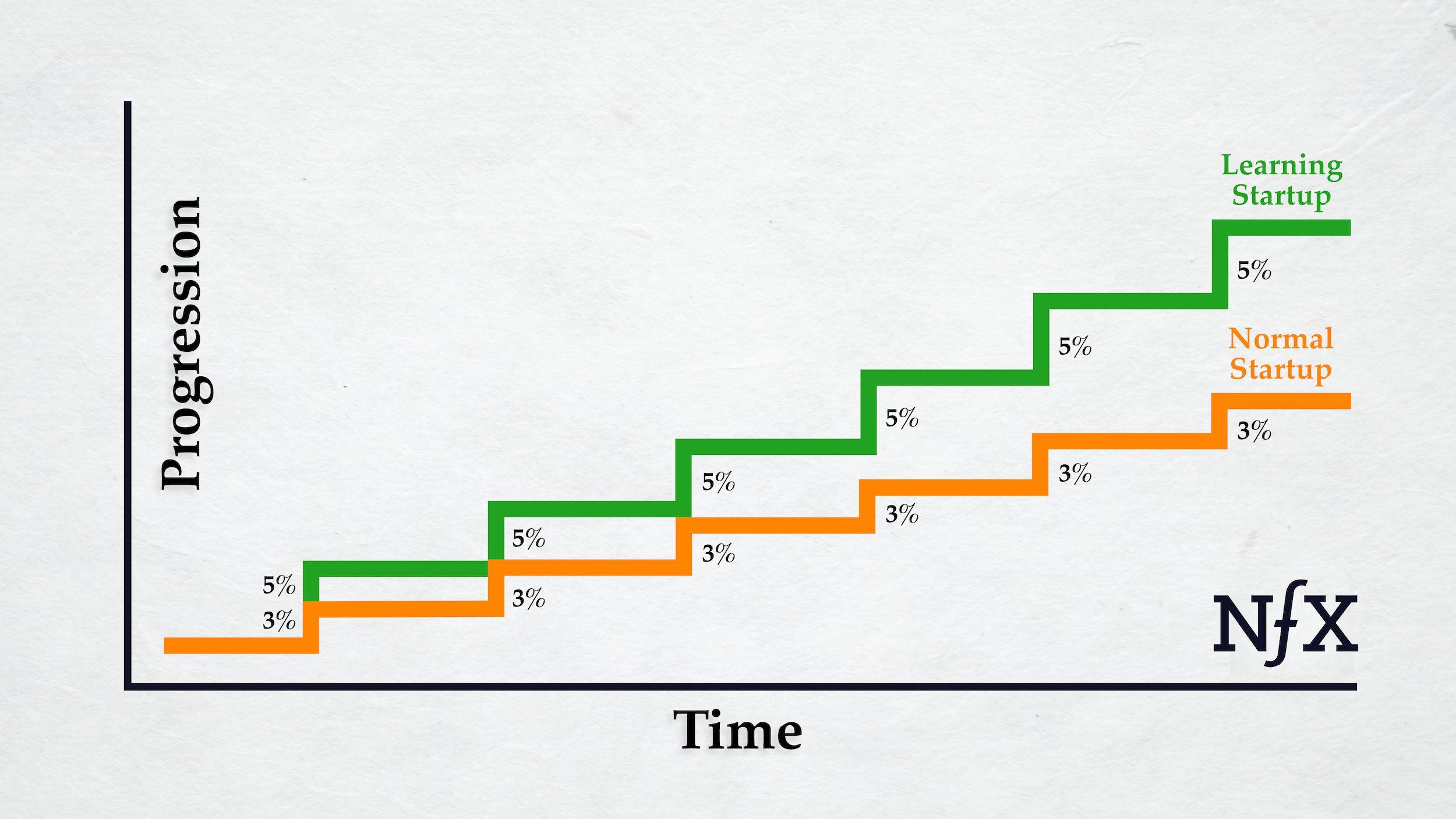

- There are a bunch of tricks for invention, none of which are overly complicated. The hard part is to stay focused on them over the course of years.

- It’s one thing to implement something new, but I’ve met too many CEOs who read a book, listened to a podcast, or had an idea, only to implement it and immediately move on to the next thing.

- They don’t come back in a couple of years and ask the question, is that insight we had a few years ago, still adding value in the way that it was?

- That’s a hard thing to do when you get your energy from creativity, but it’s essential for creativity to actually compound value over time. Otherwise, you just end up with a pile of what was once creative that is now just weight.

- What allowed us to scale without that weight included careful organization.

Inventing AWS, Alexa, and Amazon Prime

- We had this idea that as often as possible, when you put someone in charge, you make them single-threaded. So when Jeff wanted to start AWS, he made Andy Jassy single-threaded. Andy didn’t work at anything else other than the business plan for AWS.

- When we started Devices, Steve Kessel, who was running the books business at the time, moved over and took over with no other responsibilities. He went from running the largest business to having an assistant, and nothing else, except for this nascent business.

- So that’s the first thing: single-threaded leadership.

- Second, and this is easier now with cloud services, but at the time, being disciplined about software architecture was vital because you can slow down and end up with the organization following a bad architecture if you’re not careful, or worse, the architecture following a bad organization.

- We had a lot of work to do to create a service-oriented architecture out of a more traditional legacy architecture. That may have actually been the hardest management problem in those middle years.

- We measured everything, and we focused on the inputs, not the outputs. So teams rarely worried about quarterly revenue.

- If you focus on inputs, you’re less likely to worry about the inter-organizational output stuff that a lot of teams fight about.

- I’ll highlight one more. When you choose to invest in so many different businesses, something many consultants would tell you is crazy to do, you have to make sure you protect the nascent businesses because the mothership is going to want to destroy them.

- I think Jeff (Bezos)was brilliant at this. He carefully protected Andy and AWS, Steve and Dave Limp and Devices — even though it may not have felt that way if you were Andy, Steve, or Dave.

- He made sure the third party business that we built, where we invited other retailers to sell against our retail team in the same store, was protected.

- The only way that that sticks is if you keep the retail business from crushing the third-party business, which Jeff did masterfully. We made sure that third-party sellers were treated as customers from the beginning.

How do you create courage in the people who are working with you?

- My mentor, Andre Tramper, once said to me, “Don’t hide all of your peculiarities. You will make more authentic connections with people if you have the courage to reveal yourself.” That’s where you start.

- You let them know when they fail that you’re going to separate the problem from the people.

- If they’re failing because they’re going to be unsuccessful, you help them to move on to something where they can succeed.

- But if they’re failing because of things that aren’t within their control, let them know that you’re going to work with them to remove those barriers.

- A lot of it is setting up a relationship with people that lets them know that you’re going to hold them to high standards and simultaneously support them if they fail.

- I have this great example from the first business I was running. It was my first quarterly review with the CEO, Larry Boss.

- I was nervous. Business was doing okay, but not great.

- My assistant comes to the office, and she’s a little frantic. She says, “Jeff, Larry’s on the phone. Pick up the phone.” So I pick up the phone, it’s Larry. He says, “Jeff, it’s Larry.” I said, “Hey, Larry, what can I do for you?”

- He said, “Looks like we have a review coming up tomorrow. We’re reviewing all of the chemical businesses. Big day for you. I went through the books and I want you to know that I think the world of you, I think you’re going to be a fantastic leader, you’re going to have a great career, but tomorrow is going to be a rough day.”

- I didn’t sleep. I was way over-prepared. I got through the day fine, but I wanted to come back for more.

- He was great at setting a high standard and letting you know that he cared about you.

- He was great at making you terrified of performing poorly for him, but even if you had failed, and he was mad, you still kept coming back for more.

6 Distinct Phases of Leadership

- There are these moments when cultures change and the task of leadership changes. I would argue that if n equals the log base 10 of the number of people, then there are these distinct phases of leadership: n equals 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Amazon is now at 6.

- So when you have 100 people or less, you can know everybody, you can manage by walking around. You certainly know your 10 most important people really well if you do this right.

- But when you get to n equals three and four, you’re depending on others to create that same environment where people will take risks and learn from those failures. That’s harder to do.

- It requires some different kinds of mechanisms, some different kinds of projection.

- At n equals five or six, I found that I had to do a lot more video work, for example, to project and to try to be authentic on video.

What do you think makes someone a great teacher?

After Wilke retired, Bezos said: “Since Jeff joined the company, I have been lucky enough to have him as my tutor. legacy and impact will live on long after he departs. He is simply one of those people without whom Amazon would be completely unrecognizable.”

- I think competence matters. It’s hard to teach something that you don’t thoroughly understand.

- Early in my career, I was collecting experiences so that I could maximize option value. I was achieving competence in a bunch of areas that made it easier for me to teach.

- You have to be a lifelong learner to teach. Teaching isn’t just getting to a certain point and then using whatever you’ve learned without any new learning. I think it’s an iterative process.

- The best teachers are also often the best learners.

- The communication style and ability to relate to people in an authentic way helps you be a better teacher. Also, finding mechanisms to project teaching broadly as an organization grows is important.

- It’s a certain kind of skill to be able to use your voice and your face to project what you’re saying, that you believe it, and that it’s coming from an authentic place.

- If you don’t really believe it, and you’re trying to do this on video, it’s going to be super hard for others to believe it too.

- Part of learning is believing the teacher. You can be skeptical, but you have to believe that the teacher has competence.

- What makes you a great teacher is that you care about people, and you’re a great learner.

- I hope I spent the time to treat teaching as a task of paramount importance as opposed to something that you do reluctantly.

What’s Next for Jeff Wilke

- For the last six months or so, I’ve been working on a company that we launched in January called Re: Build Manufacturing.

- The CEO is a classmate of mine from grad school at MIT. I’m the non-executive chairman. We have a great small collection of investors and a really good board.

- The mission is to build a multi-division industrial company that will build US factories and employ US workers.

- We’re starting with a number of acquisitions of companies that either have physical technology (material sciences, physics, mechanical engineering) or have established product-market fit with significant revenue, but don’t have the latest technology.

- We’re combining these acquisitions into an operating company with a healthy dose of computer science and automation that we think can compete effectively against global competitors.

- I can imagine over time in renewable energy, vertical farming, and other industries that are new and have physical componentry to them, they are going to need manufacturing, a manufacturing supply chain, and we’re here to help.

- We want this to be a lasting, important industrial company, and we want to build a culture.

- In fact, one of the first things we did was write the leadership principles for Re: Build Manufacturing. They’re called the Re: Build Way.

- We’re hoping that they have the same cultural effect in some small way that they did it at Amazon.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.