In my conversation with Scott Cook (Co-Founder of Intuit, and formerly on the boards of eBay and Amazon simultaneously), he shared a story that has stayed with me about the role of network effects in an early battle between eBay and Amazon.

“John Doerr and I were skiing in Aspen over Christmas, and Jeff Bezos emailed us saying, ‘Hey, I’m in town. I’d like to take you guys to dinner.'”

Bezos told them “Well, I want you both to know that we have been secretly building our eBay killer… we will launch it on Tuesday. I’m sure you’ll want to, of course, leave the eBay board because they’re going to be toast. I want to give you that heads up.”

But what Scott knew, and Jeff quickly realized, was the power of network effects. And more specifically, that not all defensibilities are created equal.

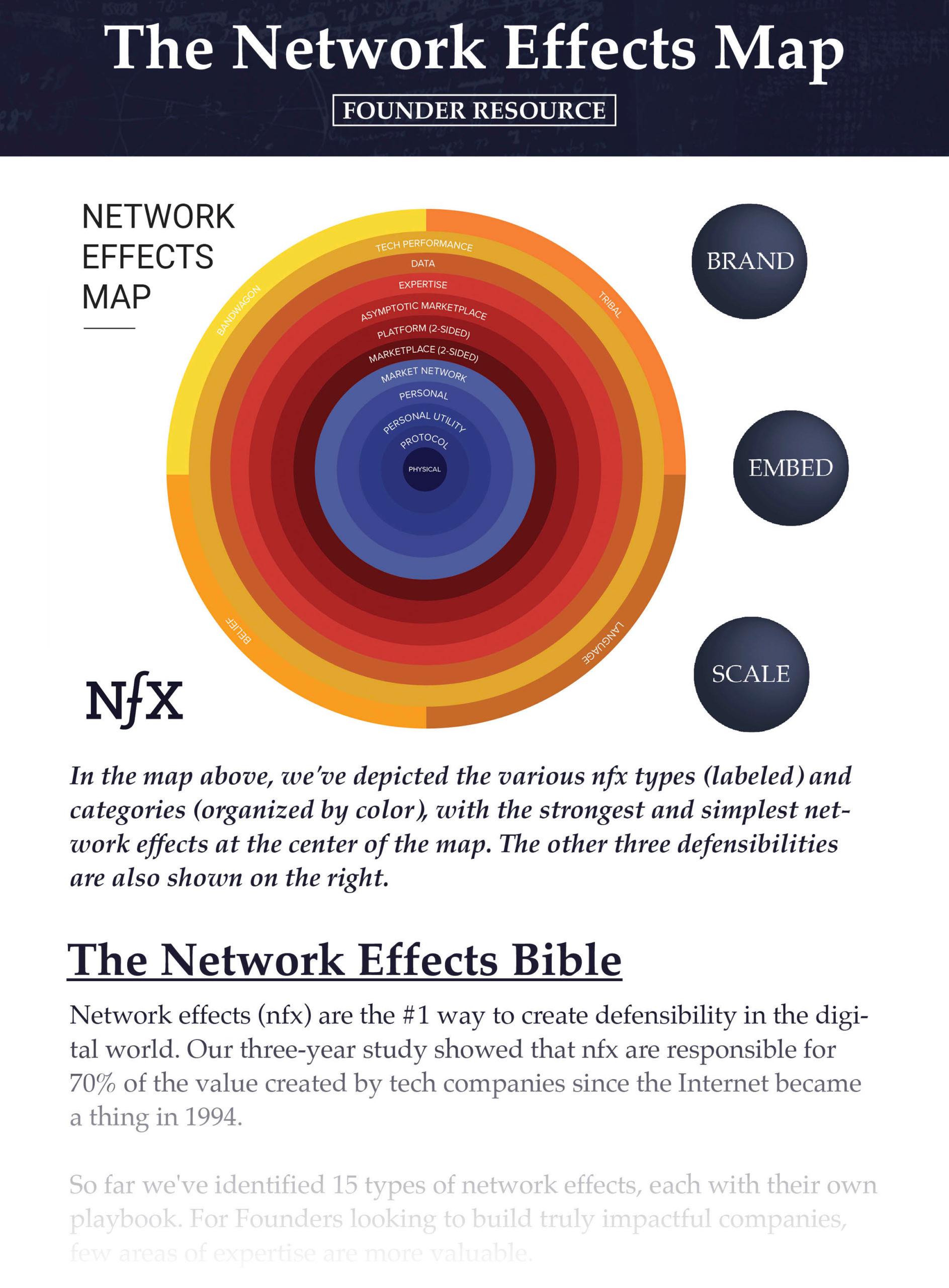

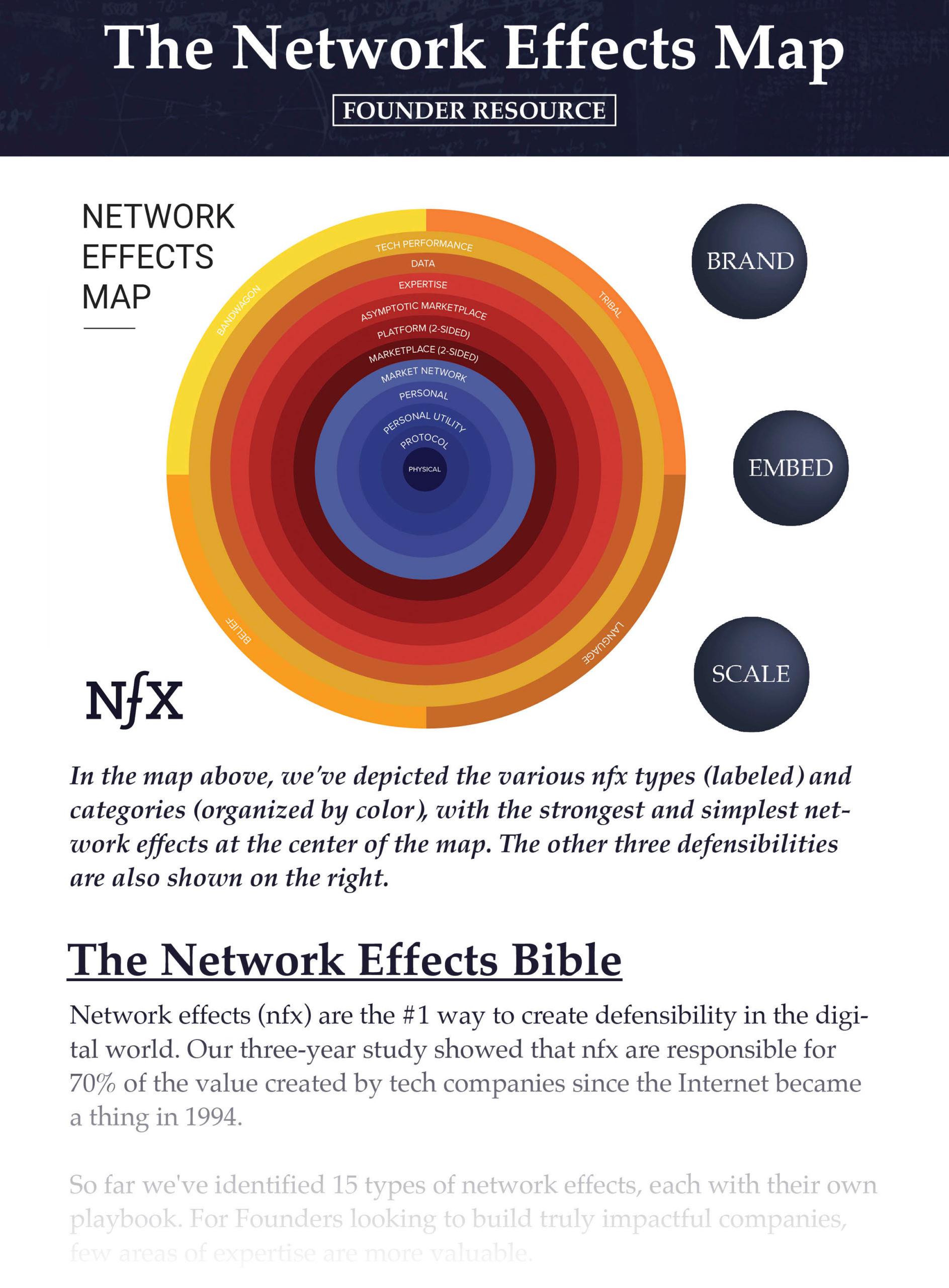

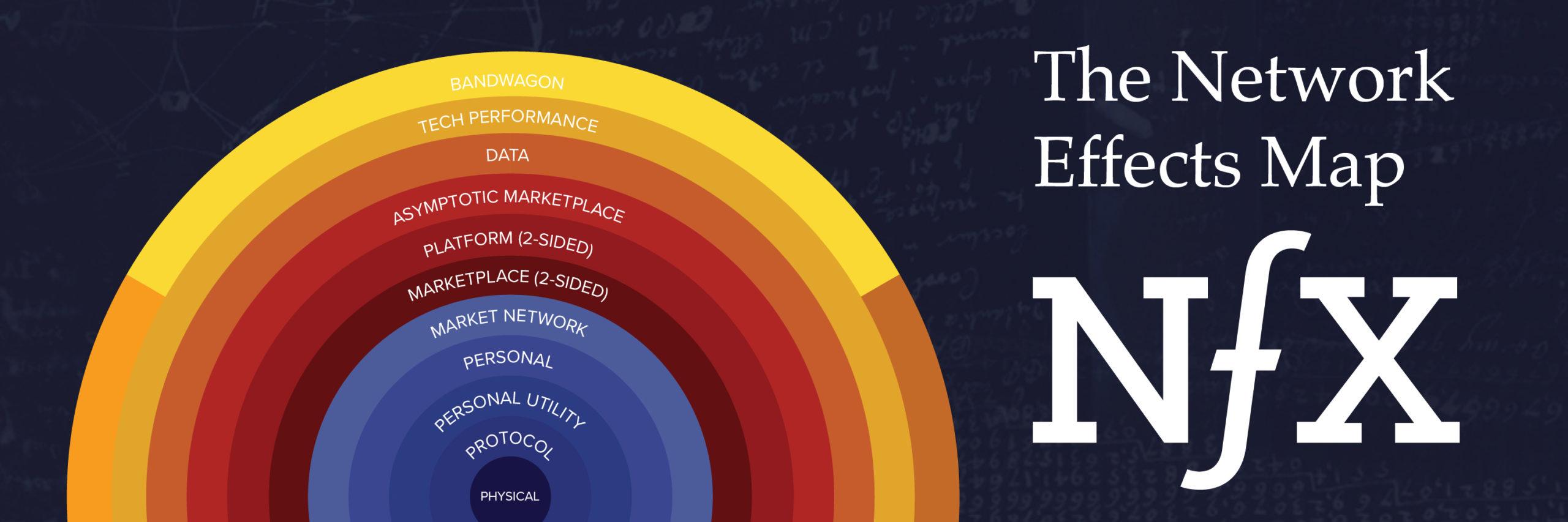

As we at NFX have said, there are 4 defensibilities in the modern age: Brand, Scale, Embedding, and Network Effects. Of these four, Network Effects is by far the most powerful.

To understand why, let’s have Scott unpack the rest of that dinner conversation with Jeff and break down how Founders should carefully choose their durable, competitive advantage.

The Original Two-Sided Network

- It was in the late ‘90s. For some crazy reasons, I managed to be on the board of Amazon and eBay at the same time.

- eBay just defied explanation. I remember I first came across eBay when they were still publishing books that showed the amount of traffic and pages per user for thousands of websites. This was the early days of the web.

- Most of the pages per visit were in the two or three range. People barely used websites back then.

- But that’s when I ran across this highly engaging thing called eBay.

- I got an email from Meg Whitman and she said, “Hey, Scott, I’ve just joined this company eBay as CEO. I’d love to talk to you about joining our board.”

- I said, “Well, I don’t know what eBay does, but I really want to learn.”

- I found out this amazing thing. They opened up a retail store, Pierre (Omidyar) did, and he left it empty. He put nothing on the shelves and the world came and filled it up with merchandise.

- It was the original two-sided network executed marketplace done in software. It’s just amazing how the thing grew.

Jeff Bezos’s Warning in Aspen

- John Doerr and I were skiing in Aspen over Christmas, and Jeff Bezos emailed us saying, “Hey, I’m in town. I’d like to take you guys to dinner.” So we left our families and had dinner with Jeff.

- Partway through, we said, “Jeff, so why did you invite us to dinner?”

- He said, “Well, I want you both to know that we have been secretly building our eBay killer. We didn’t want you to know, Scott, because you’d have a conflict with that. But we will launch it on Tuesday. I’m sure you’ll want to, of course, leave the eBay board because they’re going to be toast. I want to give you that heads up.”

- So I said, “Well, Jeff, you know how I love what you’re doing. Amazon is phenomenal and you have truly vanquished a number of competitors already. 359 degrees around you, you have mediocre companies as potential categories you could enter, except one. We have a company with a powerful network effect. This is not going to end very well.” But he was undaunted by my advice, and I watched what happened.

- It turns out that within a matter of a couple of months, the two most powerful companies in the digital world, which at the time were Yahoo! and Amazon, both decided to attack eBay with clones.

“This is an effect the world has never seen before”

- Amazon and Yahoo! had done excellent clones of eBay. In fact, the software was better, the sites looked better.

- eBay at the time looked more like Craigslist, and these two competitors had really slick working sites plus they were being advertised from the most powerful home pages in the business for several months.

- Yahoo’s homepage, the most powerful page in the world, did nothing but advertise Yahoo! Auctions.

- Plus they had a major pricing advantage. eBay’s take rate at the time was around 6% of every transaction. The take rates at Amazon and Yahoo! were zero, it was free.

- You would think that a free competitor, advertised and delivered by the most powerful entrants in the world would crush little eBay. But in fact, the reverse happened, they bounced off, nothing happened.

- eBay kept growing. Amazon and Yahoo! couldn’t get traction even though they were free.

- That got my attention. It was something more powerful than I’ve ever seen in business.

- I started seeing the Intel microprocessor, the Microsoft Operating System, Word and Microsoft Office, and all of a sudden the picture came together.

- Shoot, there are a number of companies that have built some phenomenal competitive advantages where no attempt to disrupt them has had any effect and where their share positions get closer and closer to 100.

- This is an effect the world has never seen before, except in a government-granted monopoly, which is increasingly rare nowadays.

- So that’s what got my attention, then I started studying them in earnest.

Amazon’s Long-Term Play

- Ultimately, I had to choose what board to stay on because Amazon and eBay stayed rivalrous. I elected to stay on the eBay board.

- Now, Amazon has gotten very large and does have a big marketplace. More than 50% of their transactions are now in their two-sided marketplace, but it just took 20 years.

- They decided to really embrace the two-sided market. They were the first merchant in the world ever to do that — to really embrace a two-sided market after having put the merchandise on the shelf.

- The whole move into Amazon auctions was a move there. Jeff got them.

- Jeff is so smart. He got the mind shift early. He just had to work.

- Initially, they couldn’t win by going headfirst into eBay. They had to find a way to work around them.

“You’re Roadkill” Without A Durable Advantage

- Maybe there was a time when you could start a company and not have to worry about competitors. But in the world we live in today, the giants whether it’s Facebook, Google, Amazon, or other startups with the vibrant startup infrastructure, have such speed, and agility, and resources.

- You have to assume that there are going to be other people trying to do the same thing as you, either at the same time, or once they see that it’s successful.

- If you don’t have a source of durable advantage, well, you’re roadkill. All of your work goes to nothing, and you get crushed.

- Not only to survive, but to thrive, the size of your profit stream is largely a function of your size of durable advantage.

- If you don’t have a durable advantage, you’ll have 18 competitors, and they’ll compete you down to no economic return.

Types of Durable Advantages

- James Currier: We published a perspective that in the digital age, there are four major defensibilities. If you discount IP, and particularly in software, it’s tough to use IP. You have brand, embedding, scale, and then you have network effects. We posit that network effects are the greatest of the four.

- Yes, my framework is similar to yours. The conclusion is exactly the same, that the giant in the room is network effects. The others all have their flaws.

- A traditional advantage was fixed costs scale leverage. This advantage assumes that nobody else can put the fixed cost in. Well, today with the tech titans out there, they can pay the fixed cost in a blink.

- Fixed costs scale leverage assumes a capital-constrained world, and we live, at least in tech, with companies that are seemingly capital unconstrained so scale advantages don’t have the power they used to.

- One that gets some discussion is switching costs. There was a time when certain companies had unique access to a source of supply, like De Beers with diamonds, but you don’t tend to see that anymore.

- The assets of the new economy are just data and software and they move around very easily.

- I don’t think brand is a worthy defense at all. I’ve seen companies with phenomenal brands get crushed in a matter of years.

- If you go back to the early age of PC software, the best brands in the industry were Lotus 1-2-3 and WordPerfect. Microsoft crushed them in a matter of years, and they had the brands.

- I don’t think brand buys you very much. The best brand in search was AltaVista or maybe Yahoo! and now they’re roadkill.

When Brand Was Important

- If you look at where brand used to matter a lot, it was in consumer household products that may appear on a grocery or drugstore shelf.

- Those are product categories where the consumer already has been using the product for years, just ran out, and has to re-buy.

- You walk by that shelf twice a week. The product only costs three bucks.

- All they have to do to get you to try their brand is get you to reach out toward the shelf.

- Maybe brand image could make someone who’s going to buy anyway move their hand 20 centimeters to buy your brand. But we’re not talking about that world.

- The world we live in, there’s no one walking by a shelf, they didn’t just run out of your product. You’re trying to get them to do something new, generally that they’ve never done before.

- Brand does not build much of an advantage anymore, nor is it much of a defense. You need something more powerful like network effects.

A Rare Advantage of Southwest Airlines, Toyota, and Amazon

- There’s an HBR piece that identifies another durable advantage, they call it multi-factor process advantage.

- This is where you have a method of production that is very different from the rest of the industry and very hard to copy because it differs on so many attributes, such as Southwest Airlines.

- Southwest Airlines has been the best performing US airline for 30 years. They use their labor differently, they use capital differently, there are so many differences between how they operate versus a normal airline.

- The other airlines are union constrained and so they just can’t copy the superior method. So Southwest has retained a fairly durable advantage.

- The Toyota production system is another. Toyota makes cars in the plant in a way that’s fundamentally different than the procedures used in normal auto plants.

- Famously, they’ve allowed other car manufacturers to come into their factories, videotape, and spend as much time as they want and in the end, they’re incapable of copying.

- I would say Amazon has built a multi-factor process advantage in software development. The speed with which they can move, and innovate in a large company is impressive.

- It used to be, you build a large software company, and you get slow and stupid and not innovative.

- Amazon has kept speed and rampant innovation, despite size. I think there’s something special going on there, but multi-factor process advantages are rare. Few companies develop them.

- It’s about culture, hiring, and a real determination to do things differently.

- It requires a real invention of a better way that’s totally against the way the rest of the world works. So that’s just not going to happen very often.

What’s Most Surprising About Network Effects

- I’m still learning about network effects, there’s so much. I think most of what we will know, we don’t yet know.

- I’d say the thing that’s been surprising is how small the founding teams are of some of the great network effect businesses today.

- Pierre Omidyar worked alone to write and launch eBay after what he says was a three-day weekend of work.

- What’s stunning is how tiny the teams were who built and launched the first versions of what became powerful network effects. Just wow.

- The world’s never seen something where so few can produce something with such a global reach and strength. It’s all on the back of this internet thing that someone else built for all of us.

- You can have small teams on the internet that don’t amount to much. You can have big teams too. That’s been the biggest surprise to me.

- This speaks to the capital efficiency you can get from these companies, which implies greater returns for the employees, for their stock options, which implies greater returns for the investors.

- The investment that Benchmark made into eBay was the single best venture investment ever made in world history — at that time.

- Pierre not only coded it himself, he launched it himself. He was the only employee for many months.

- Only when so many checks came in that he needed help cashing the checks did he finally hire somebody. They had remarkable efficiency in both labor and capital.

Do you have a network effect?

- One piece of advice I’d give Founders would be to figure out early on if their company is really a candidate as a network effect or not?

- Just being two-sided does not mean you’re a network effect.

- I think a key to that is understanding multi-homing. Is there a natural incentive for the participant, or the participants on each side, to deal with only one platform? That’s single-homing. If that’s the case, then there’s a much stronger case that you can build a network.

- On the other hand, if the participants on one or both sides can play the field easily, then you’re not going to have that durable advantage.

- You see some of this with Lyft and Uber where it’s very easy for drivers to run both and passengers often have both too.

- That’s why you have two of them that are losing money instead of one that’s successful, or profitable, at least.

- I think that’s an early thing to figure out. Run the test of whether your company really turns out to be a network effect or not.

- To do that, you would have to read up on them. You’d have to think about them, you’d have to study them, you’d have to see what has produced network effects in the past.

- If you’re a Founder, to try to get a better sense of whether you really have one or not, you have to find people who are knowledgeable about it.

- I think the stuff that you are producing at NFX may be the most current, and most inclusive, even beyond what I knew. That’s where I’d send people first to learn about network effects.

Solving the Chicken-or-Egg Problem

- Building a 2-sided marketplace is like running two companies at once. I see companies, when I coach CEOs and our internal startups, they’re often much more comfortable at looking at one side of the market, and they tend to forget the other.

- They’re trying to solve the problem on one side by using the other side. But in fact, you have to solve some large problem for each side and the problem will probably be different.

- For PayPal, a buyer wants to be able to buy the item and a seller wants to be able to collect money. You have to solve each problem on both sides, otherwise, you won’t get people in.

- I find teams will be so focused on one side and just make assumptions about the other side.

- You have to understand, what’s their biggest problem? And how are you going to solve it? Because if you don’t solve it, they’re not going to come.

- On each side, there has to be a large problem that you can solve well by participation in the network.

- Then, there’s the chicken-or-egg problem.

- If you can’t start getting scale, you’ll never get off the ground because these will only work when you start getting volume.

- Our strategy team at Intuit have a few different ways that we’ve observed people solve the chicken-or-egg problem:

-

- Virality: LinkedIn did this where members invited other members.

- Incentives: PayPal did this where they paid participants five dollars if they brought in a new participant and they also paid the new participant five dollars.

- Build something with standalone value (that works well without the other side): OpenTable did this by first selling a software platform to restaurants for managing reservations. You didn’t have to be part of their network for that to be of value.

New Possibilities at Absolute Zero (Free)

- A lot of our interactions are being facilitated by having these global networks on the backbone of free digital bits.

- Network effects companies are a kind of national organization, which can take advantage of the power of free.

- It’s like science. When you get things to absolute zero, the rules of science change.

- Similarly, in economics, the rules are going out the window. When you get to free, you start getting an unlimited supply of free things.

- Thanks to Skype, we have free worldwide video calling.

- Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter give us the ability to stay close.

- We take it for granted now but if you go back 50 years, they would say: “The world could never get that good. That’s so far beyond any belief, only a god could deliver the thing you just described.”

- Look at the ability to get a ride wherever you need it and the ability to find apartments that also give second incomes to homeowners.

- This is a miraculous world we get to live in.

- I think of Wikipedia. Did you know a destitute girl in Bangladesh, whose family has a phone and a data plan, has more information at her fingertips for free, than Bill Clinton had as President?

- This is unbelievably powerful, thanks to the vast contribution network effect around Wikipedia.

- What a world we get to live in.

You can listen to the podcast conversation here.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.