The new American dream is underway. The current US educational industrial complex is not serving young people anymore, and entrepreneurs outside the system are creating new alternatives.

Best example: Austen Allred, Co-Founder/CEO of Lambda School. With a perspective earned by dropping out of college, setting his own path, and now building a successful company and movement to change education in our country, Austen sees our educational past, present, and future in ways few others do.

In this essay, we break down traditional and contrarian thinking on how we are educated, challenging what has gone unquestioned for decades:

- The Psychology of Traditional College: Why “Normal is a hell of a drug”

- Faulty Mechanics: The problem with America’s “Single Model” education system

- The New American Dream: How “permissionless learning” unlocks opportunity

- 2 Trends to Watch: What Austen is seeing in the future of education

+ more

It’s difficult to pull away from the gravity of doing what everybody else does, but when you’re able to do that, you can see the world differently and do what you think is right.

The below are highlights from my recent NFX Podcast conversation with Austen.

“Normal is a hell of a drug.”

- The notion that someone would drop out of college seems crazy, but to me, I have a hard time wrapping my mind around the idea that there is no other way to obtain knowledge than within the four walls of a university. I think we’re pretty closed-minded as far as that goes.

- The hard thing is that your family is legitimately concerned for you. They think you are misguided and you are going off the right path and you are putting yourself in a place of danger.

- But all the same, it’s still hard to look at everybody around you, that is doing and recommending a path, and say, “Actually, I’m going to do something different that’s very much unproven and unguaranteed.”

- Now it’s funny because, in my networks that I’m surrounded by, I spend more time with college dropouts than I spend with college graduates.

- In many instances, some of the smartest people I know dropped out of high school or graduated high school when they were 15. Most of them were able to think for themselves at an early age.

A “Single Model” Education System in the US

- I think America is drunk on the idea of a university being the only possible path to higher education and to jobs and job training and skills achievement.

- That’s really only an American phenomenon, outside of the US there’s a bifurcation of skills training and universities, but we’ve fallen into a single model in the United States and I think that’s pretty broken.

- I think the average person when they hear me talking about college comes away saying, “Well, what’s so bad about college? Isn’t it a good thing?”

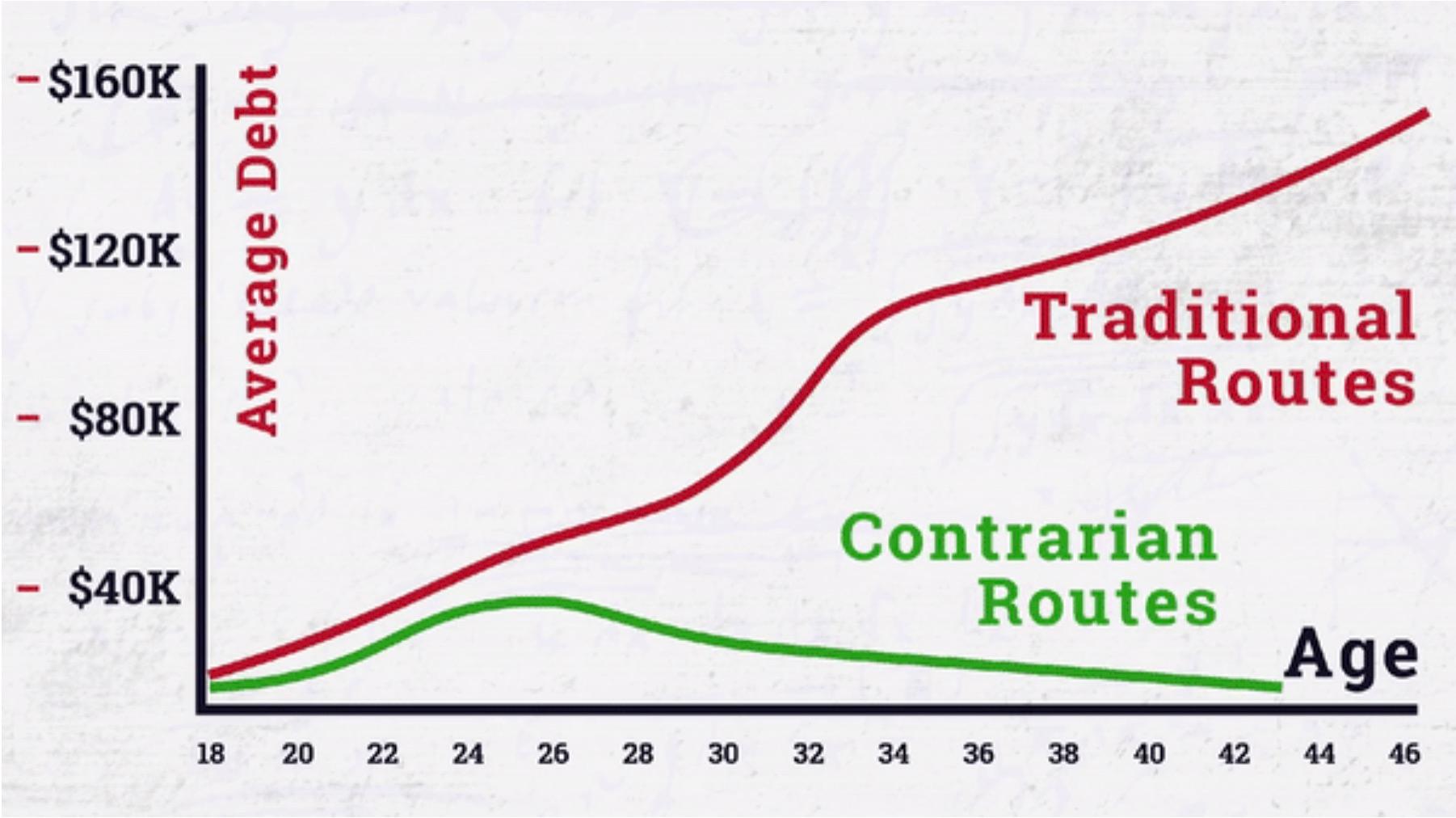

- I don’t have a particular qualm with college per se. What I have a problem with is the high cost of college, and also, I think an aspect that’s very underestimated is the long amount of time.

- I think we underweight the opportunity cost of the four years we spend in a university setting.

- I don’t know anybody who would elect to hire someone who’s a fresh grad versus someone who has four years of experience in the field that they’re in.

- If anything, the current education system in the US is becoming more entrenched with laws, regulations, and government-backed financing operations.

- You can’t really get a Pell Grant today to go to a trade school. You can only get a Pell Grant to go to a Title IV approved school, which generally speaking means a four-year college or a community college.

- So the assumption is that if you’re playing by the government’s rules, you will go to a university, otherwise, you’re on your own.

Permissionless Learning

- I think, first and foremost, a lot of people don’t believe in the American Dream anymore.

- A lot of people for one reason or another believe that your state in American life is determined by your ancestry or your privilege or your race or your wealth.

- Of course, all of those things factor in. They’re all meaningful and they’re all real.

- But my message is, and we don’t cater to every single person, but for those who are capable and interested in software engineering or data science, you literally can create wealth out of nothing. You literally can learn skills without anybody’s permission that allow you to do work that is incredibly valuable.

- The permissionless aspect of it is incredibly important. There’s nobody that can actually hold you back.

- There are still resource constraints that are tricky and you have to dance around those, time, money, and availability, which are non-trivial. But I watch every day five, ten, or a dozen students increase their income by $50,000 a year.

- The true definition of the American dream that I would select, and I’m sure it varies based on which dictionary you’re looking at or which set of people you’re speaking to is self-determination.

- You can call that freedom if you would like, but for me, it’s one’s ability to carve one’s own path and do what you would prefer to do.

- For most of our students, frankly, that is constrained by money. It is a grueling existence just to put food on the table and it’s hard to escape that reality.

- If you’re making minimum wage, it’s really hard to go to something higher. But we believe and we see that it’s possible, and we watch it a dozen times a day.

“Building the American Dream as a service”

- There’s obviously the skills training aspect of Lambda School and the fact that you don’t have to put any tuition down upfront. As long as you have access to the internet, you are eligible to be a Lambda School student.

- We don’t look at your financial means, credit history, work history, or grades, we don’t really care about any of that in ways that other schools or other institutions might.

- We teach you the skills, but we also help you build, or in some instances, we provide for you a network.

- These (tribal) network effects are incredibly powerful. We plug you into an alumni network of thousands of students. We can get your foot in the door at different companies.

- At the end of the day, we help you set a path for self-determination in such a way that in theory, we believe that if you learn to learn, you learn to pick up skills on the fly, and solve challenges as you face them, it’s pretty freeing.

- I think that’s what the American dream really is.

Education Networks, Built for the Internet

- The first layer to this network is the shared experience. You are surrounded by other people.

- You are working together with a bunch of people toward a shared mission and you’re helping each other along the way.

- We start a new cohort every month and this cohort can be relatively big. They can be cohorts of 70 or 80, but then they’re broken down into smaller and smaller groups until you have a pod of seven or eight people.

- People will move in and out of pods, but that group of seven or eight people, you become very, very close with them. You’re still close with the next 40 people and you become a little bit close with the people in your entire cohort of 80 people.

- Then, broadly speaking, you begin to feel an affinity with anybody who has the name Lambda School attached to them because you’re on a shared mission. You’re on a journey together and I think that’s incredibly important.

- The other element of it that I think is also important is the school’s incentives of the staff and instructors are entirely aligned with the incentives of the student.

- If our students don’t get hired, we lose our jobs. Our goals are the same.

- We need you to get hired, we need you to get a high-paying job, and we’re going to do everything in our power to make that happen. That’s pretty unique, certainly to my university experience, but I’d imagine to the average school. Your outcomes are not usually tied to one another in a way that they are within Lambda School.

Selection Matters, That’s Why They’re Networks

- The way you look at universities right now is 90% based on what their selection criteria are and 10% on what the course content is. That’s what shows they’re networks, selection matters a lot.

- You’ve probably never heard somebody say, “Well, I don’t want my son or daughter to get into Berkeley because they won’t be able to handle Berkeley once they’re in.”

- That’s just not a topic of conversation. Once you’re in, you’re fine.

- The average grad that you talk to would say, “The courses were difficult, but not too challenging.”

- It’s really the selection, it’s the filter on getting in.

- I’m interested to see how that evolves over time, because that used to be partially grades, partially SAT, partially character.

- We’re moving away from SAT and testing, which kind of served as a proxy for a general cognitive aptitude test or a skills test of some sort. That’s going away in a lot of universities.

- Now we’re falling back on grades and essay writing, which is a totally different filter. I’m really curious to see how that plays out over the next 15, 20 years, because we’re starting to measure a fundamentally different thing when determining who gets into which school.

Status Games Are Zero Sum

- If you were the dean of Harvard and you said, “Hey, Harvard is doing so well that we’re going to 100X our enrollment,” you would have a revolt.

- The reason Harvard is powerful is that it’s a zero-sum status signaling game of locking out everybody except for legacy people who did really well in school.

- But in order to have a school that really scales, you have to rely on something other than just the signaling. I think schools are learning that.

- I think that gets a lot better in the university system if you start to look at university 50 and down in the rankings, even though I think the rankings are pretty skewed and everybody’s gaming them anyway.

- The average university in the United States will accept more than 50% of the people who apply, so it’s not a signaling game, it’s actually an education and skills training game. But the top 20 universities are something fundamentally different.

Newer Sources of Status

- As a couple of examples, Y Combinator became one where by virtue of being a Y Combinator Founder, doors are open to me that were not open before.

- That wears off as you get bigger and bigger and as you’ve raised hundreds of millions, but for your first couple of million dollars raised it’s 10 times easier as a Y Combinator Founder.

- I think the Thiel Fellowship was a really, really interesting experiment where they basically said, and I’m putting words in their mouth that they may or may not agree with, but they’re betting on the fact that it was the selection criteria of the various universities that mattered more so than the education.

- So they said, “We’re going to take people who frankly are qualified for the Ivy Leagues, but we’re going to have them not go into the Ivy Leagues and they’re going to go start their own things.” And out of that, you have Figma, Ethereum, and several multi-billion dollar companies and a lot of successes.

- I think it was a very expensive way for Peter Thiel to say, “Look, you’re not filtering for Berkeley grads because Berkeley is such a great institution, you’re filtering for Berkeley grads because they’ve had to jump through so many hoops to get into Berkeley. The person who’s willing to jump through that many hoops and who was skilled enough to jump through those hoops will tend to do well in life.” That phenomenon is fascinating to me.

- We always find a way to signal status.

History of Online Education

- If you look at the history of what I’ll call online education, somewhere about 12 years ago there were these things called MOOCs, Massive Open Online Courses, that everybody was extremely excited about.

- MOOCs were basically you’re going to point the camera at a Harvard lecturer, record their entire class, and put it online, homework and all.

- There are large-scale MOOC providers such as Coursera, Udacity, edX that work directly with universities, or there are unofficial, unaccredited providers such as Udemy, or people can use Teachable to create their own.

- I think what we found in that experiment was the completion rate was just really low – as in like 3%.

- The analogy I would use is the concept of providing the content was actually not that novel or unique. In fact, you can get any of that information in a library and have been able to for 200 years.

- Maybe having a video recording of somebody explaining it is marginally better, but it’s not 10X better than what happens in your average school.

- What is happening now is that we’re adopting internet native education. How do we take this medium of the internet and morph it around the people instead of just taking what happened in a physical classroom, recording it, and putting it up online?

- There are different ways that you can do that asynchronously or synchronously. The more important question I think is what is the interaction like? How does a student know where they are versus where they need to go and what’s in between those things?

- How do they get help when they’re stuck? Do they feel like a part of a community or not?

Cohort-Based Education

- What’s all the rage right now, and I think the word was coined by the founder of Maven, is cohort-based courses.

- They’re going to be online and it’s going to be available asynchronously, but we’re going to re-introduce that element of community, and we’re all going to participate and work together.

- So to analogize that, there are a couple of different models. I often look at fitness as an example.

- There is now SoulCycle, Peloton, and all of these group class experiences that you can take asynchronously, but for some reason, something flips in the human mind when we know that we’re doing something synchronously with other people, even if you’re not in the same room.

- I think the founder of Peloton, and this is somewhat related to gaining skills, has done a really good job of pointing out that people are feeling a lack of community more broadly.

- He even specifically points out the decline of religion and looks at what religion used to provide that is fundamental to a human need.

- How can we provide that sense of community, that sense of helping people, that sense of something being greater than oneself?

- He very explicitly crafted Peloton to recreate that experiment. They studied ancient texts and how candles used to set the mood and they built the lighting in their studios accordingly.

- Whether it’s related to knowledge acquisition or not, I do think there is something to the element that where communities are is where we want to go.

- If you want people to gain skill acquisition, the number one problem is making them show up.

- If you’re part of a community working together toward a shared goal, you’re going to spend more time, you’re going to show up, and that is problem one to be solved for education.

One-on-One Coaching

- There are now more kinds of personalized customization models.

- An example of that would be Future Fit or Noom where you have a personal trainer who works with you asynchronously, and they’re going to provide you your workout every day.

- It’s an Apple Watch app and it’s going to monitor your movements and give the data back to the instructor who’s going to be your day-by-day guide.

- There are also AI-based coaches that will look at how you code and tell you how to fix your formatting, or how to rename your variables or whatever else. They’re still in their infancy.

- If they are self-driving cars, now there are cars that are pointing out when you’re veering outside of the line. We’re not at level five autonomy by any stretch, but you could imagine 10 years down the road, everybody basically having their own private tutor available at all times that’s very cheap.

- One-on-one tutoring has been a superior way to learn forever.

- There’s a study by a gentleman named Bloom, he calls it The 2 Sigma Problem. It’s when students who are working one-on-one with a tutor and working until mastery then moving on, instead of working in a big group, will perform two standard deviations better than the mean. This means the average student in that environment will beat out 98% of students in the average environment.

- Researchers in academia and pedagogy have known that for some time, it’s just incredibly expensive to give everybody their own one-on-one tutor.

- Online environments between cohorts and personalization are making that possible for a fraction of the price.

- We’re still in the early days of that, but it’s starting to work. We’ve seen early, early aspects of it.

- I don’t know how this will shake out in the long run, but doing things online synchronously with large groups of people and having a level of customization that would be difficult to impossible to create in an offline world are two trends that I find incredibly interesting.

- These are two different models but they didn’t exist even five years ago. I think they’re incredibly fascinating.

Education Still Starts with Exposure

- We need exposure to a lot of different things.

- This is one of my frustrations with the fact that everybody picks what they do when they’re 18 and they’re stuck in that thing for life.

- Step one is getting rid of the concept that what you pick when you graduate high school is what you’re going to be forever, I just don’t think that’s realistic.

- I didn’t know that a lot of the people I’m surrounded by now, product managers, software engineers, and data scientists, were a thing when I graduated high school.

- My dad was an accountant, so I knew that accountants existed. I knew that doctors, lawyers, and teachers existed, and that was it.

- Counterintuitively, my guard is always up when taking advice from parents on career paths. They’re looking at the job market the way it was 20 years ago whereas you need to be looking at the way it will be 20 years from now, which is impossible to predict.

- There’s a whole world of different career paths, some of which I just didn’t know about when I was 18 and some of which didn’t even exist yet.

You can listen to the entire podcast conversation here.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.