In all the discussion about the creator economy, we feel there’s a broader historical context missing.

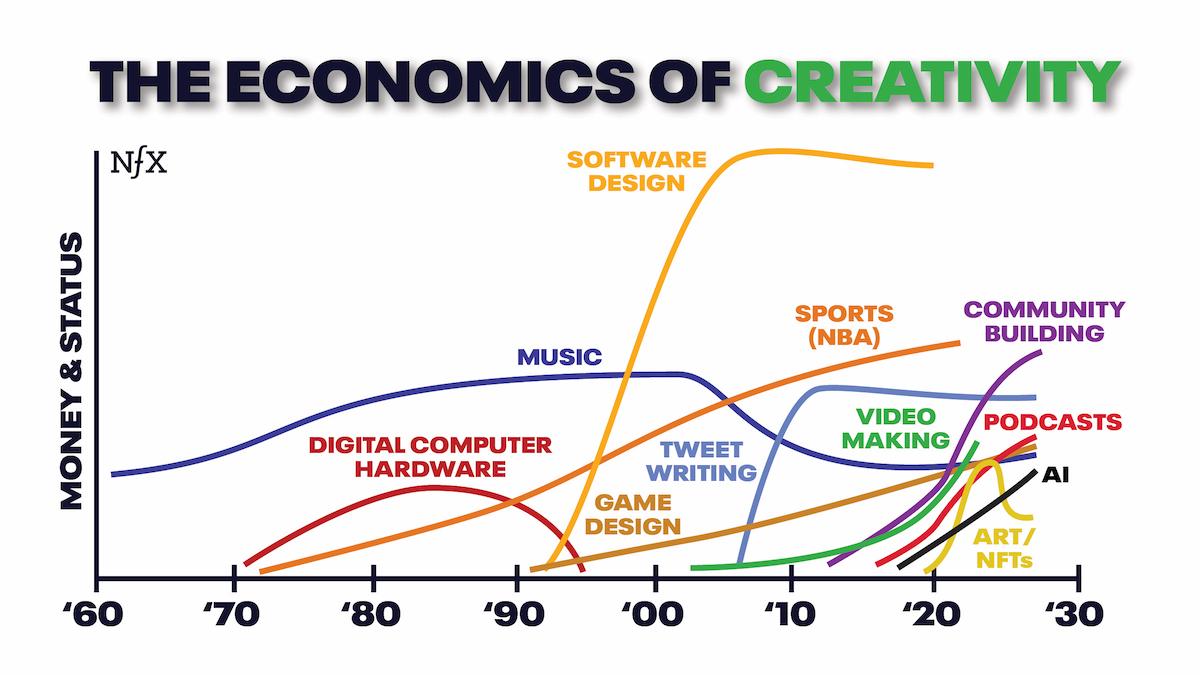

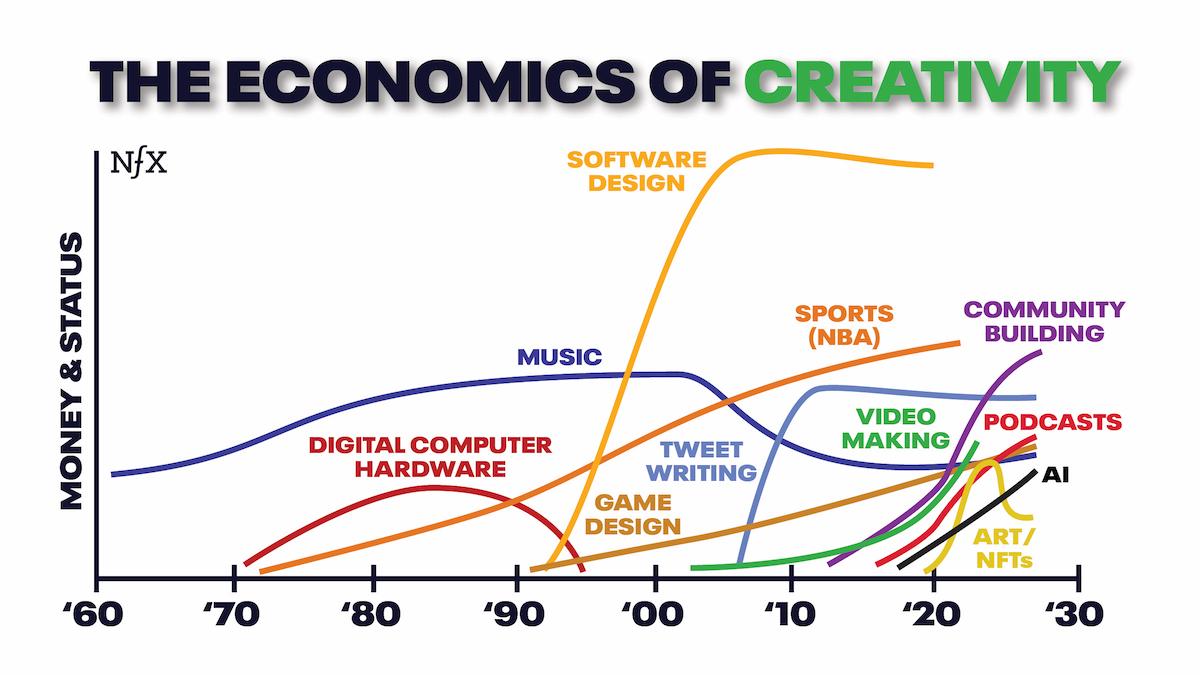

In every era, technology favors some creative skills over others with huge quantities of money, while other creative skills bring the creator little or zero money.

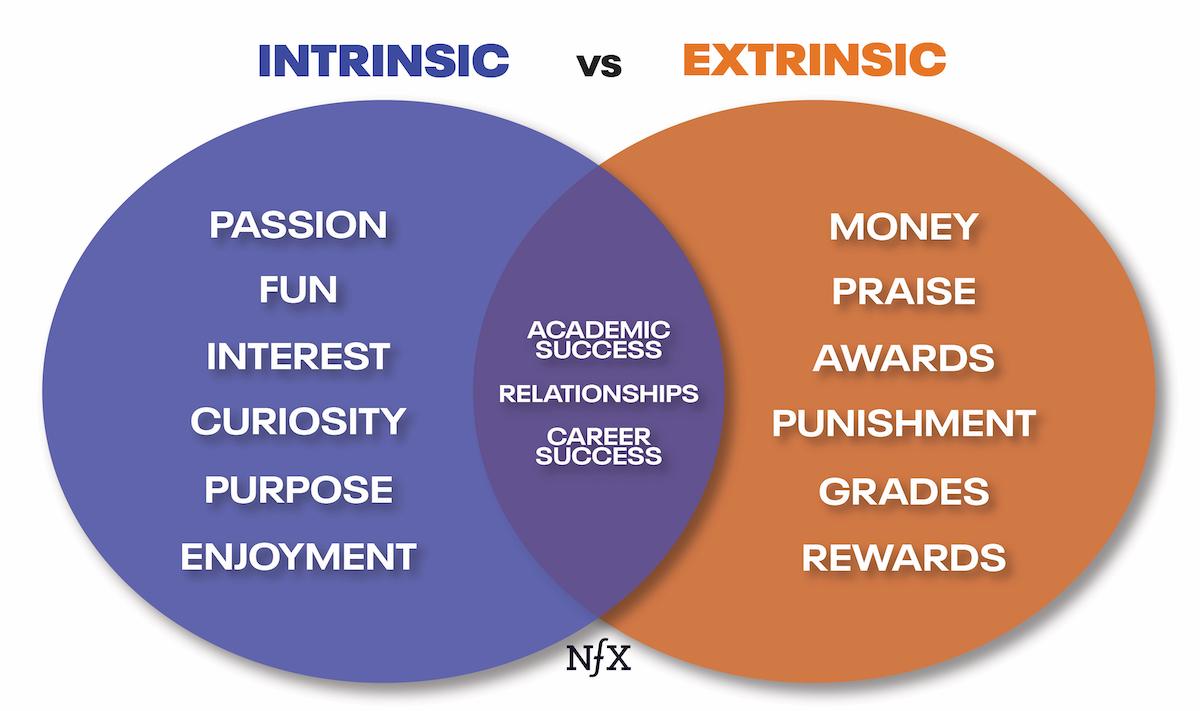

The paradox is that most creatives will create for free. We would do it regardless of money because creative endeavors are ecstatic experiences that feel inherently good to do, that get us love and admiration, that let us feel alive.

But if you want some money for your creative acts, it pays to understand the fundamental relationship between creativity, technology timing, and money. If you don’t, you’re destined to feel bewildered and frustrated that your creative skill isn’t being showered with lots of money, recognition, and status while other people’s skills are.

You also have to internalize that the economics of creativity is on a very steep power law. Always has been, and always will be, regardless of technology or geography. The #1 performer can receive 100X the #50 performer.

Don’t Be Pissed

I originally started thinking about this when I read an angry editorial about Bebo by the recording artist Billy Bragg in 2006. He was calling for Michael Birch, the creative genius behind Bebo, to share some of his earnings from the sale of Bebo with the musicians who put their music and videos up on Bebo’s site and contributed to Bebo’s popularity.

It occurred to me that Bragg felt wronged because he didn’t understand that a technology shift had taken place.

His creative skill of recording music was no longer over-compensated. He had moved far up the power-law playing the old game and had made a lot of money and fame. But the game had changed on him and he didn’t like his new relative position.

The new creative talent which was being rewarded at that time was inventing great user experiences on computer screens — something Michael Birch would probably do for free, given that it was fun, inherently fulfilling to do for him, and reached millions of people. Unlike Bragg, Birch’s particular bundle of creative talents happened to fit with the economics of creativity of his time.

Let’s look at a few more examples of how this has worked over several technology cycles.

Playing Yesterday’s Game

In the 1840s, my great-great-grandfather’s dad was the conductor of the Berlin Orchestra in Germany. (They were American). My great-great-grandfather played the cello. He married a Von Brandenberg woman; I found out years ago that a Von Brandenberg is royalty in Germany. How could it be that my dumpy ancestor, who simply played the cello, could marry royalty? It didn’t make sense.

Until you realized there was no Spotify back then. People who played in the orchestra were rock stars of their day. The conductor was too. Even the conductor’s son was part of the creative elite. Royalty lavished big bucks on musicians at that time, and, I guess sometimes, fell in love with them. Live music was the “technology” of the day, and it happened to favor the particular bundle of talents my great-great-grandfather had as a cellist.

In the 1920s, my grandfather was trying to make it (also as a cellist) in Boston. He got paid for playing his cello at dinner at the Chatham Inn on Cape Cod but he was perplexed to find he could barely support himself and his bride. When the kids came, he instead became a machinist and a forklift driver at a brewery. His creative endeavor of playing the cello no longer paid the bills because radio was the new technology, and the transition was underway from rewarding live music to rewarding recorded music. Later in his life, my grandfather would practice and play the cello for free for small gatherings. He loved it; it just wasn’t something that rewarded him monetarily.

Fast forward to the 1950s to my grandfather’s sister, Jane, 18 years younger than my grandfather, who loved to sing from the time she was three years old. It was in her nature, she loved it, and she would do it for free. But she ended up getting introduced to the new stack of music recording technology. She recorded 8 albums that were then distributed on vinyl technology and played on radio stations around the U.S.

Without planning it, her creative talent in singing matched perfectly with the recording and distribution technology of her time – and it produced money. She made $10s of millions and ended up in a $60 million house in Malibu.

Fast forward once more to the 1990s, when a friend of mine from college who won the Juilliard Prize for playing piano tried to make it as a concert pianist. She was much more talented than her contemporaries, but by the 1990s, the economics of live music had deteriorated to a $50 stipend for an hour performance. And it took her 80 hours to prepare for that hour. She still performs every chance she gets because she loves it. She’s willing to do it for free today, while my ancestor got to marry royalty 150 years ago for a similar talent.

In the 2000s, designing user experiences on computer screens with products like Bebo, Facebook, and YouTube was one of the creative endeavors economically favored by the state of technology. Software products were growing quickly on the Internet and we started to see network effects proliferate. The early examples of these software businesses with network effects are some of the most valuable companies on earth.

And poor Billy Bragg is pissed because he thought it was still the 1970’s.

The Recording-Music Example

This chart shows how technology changes the fortunes of one creative skill, namely recording music. The money flowing to recording artists dropped 65% in 15 years between 1999 and 2014 because digital music technology disrupted the mechanism the recording labels had for collecting money from consumers. With streaming technologies on the rise, and now NFTs, the tide has turned in the last 7 years. Same skills. Same inherent joy for the music makers. Very different relationship to money-making.

Writing As a Creative Skill

In the 2010s, one creative skill that produced unexpected amounts of money and status was writing. Because the Internet gives us the ability to go direct with our words to billions for no cost, writing has once again become a uniquely rewardable talent, particularly writing on Twitter. Some of our most prominent Founders and VCs are just really good tweeters. Further, we had one of the most skilled Tweeters of all time become President just eight years after Twitter launched.

Building Networks As a Creative Skill in Web3

Now in the 2020s, as Web3 develops and a new era of digital ownership begins, creatives will be richly rewarded to the extent that they have the creative skill of building community around themselves – those creatives who best invent context and stories. It might be that this skill, more than the art itself, is what triggers unusual amounts of money.

Having a network effects product and community is now even more critical. Founders need to think of their startup as a network, to think of their goal as “bonding” the nodes to their network: employees, investors, customers, and partners. This will look and feel a lot like community building, and network bonding theory brings in the math, giving you the tools to bond high-value nodes to your network.

NFTs, tokens, in-game purchases, tiered access, and many other new forms of value are now revealing themselves. These are occurring just as network formation tools are also blossoming – DAOs, Discord, Twitter, Reddit, Telegram, etc.

An enormous and rapid shift is taking place in what creative skills produce enormous amounts of money… for something these creatives might have done for free a mere 24 months ago.

Founders Are Artists: What Is Your Creative Act?

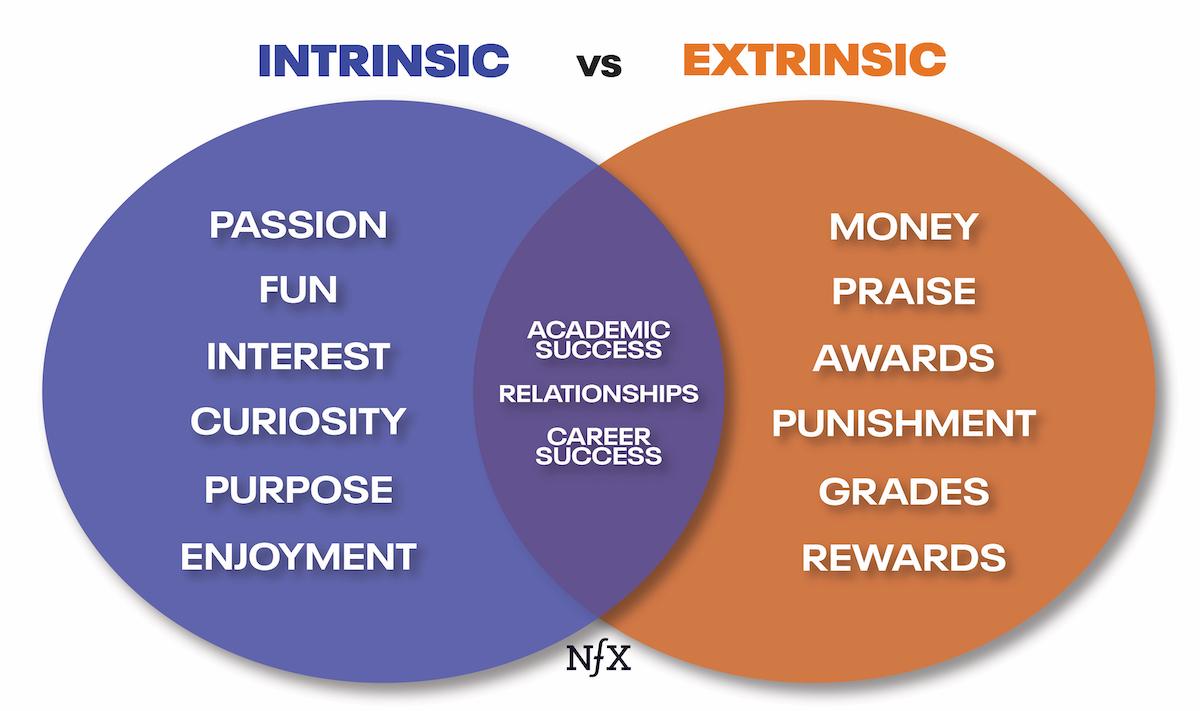

I think we’re all trying to figure out what our creative acts are during our lives. There’s part intrinsic motivation for the joy of it, and part extrinsic motivation for money, status, etc.

You need to decide where you are on the spectrum between intrinsic and extrinsic rewards.

Is it about the money and extrinsic rewards for you? Then examine the technology of your time and force-fit your interests to conform to whatever art lottery is being played at that time. Find a rewardable talent. Intentionally develop those skills. But remember, the economics of creativity are always on a very steep power law, regardless of technology or time in history.

On the other end of the spectrum, if for you it’s all about the art, the magic, the connection, the joy, then just do it and don’t worry about the money. Don’t confuse it as a way to pay bills.

And be careful when someone says they “should” get compensated more for their creative acts. There is no should. There is only the technology of that time.

With the explosion of digital ownership, we’re going to see a lot of different people find their own creative acts. Those who have a skill that lines up with today’s technology will be disproportionately favored. Many of them will be rewarded with status and wealth in ways they never would have before, because we are no longer isolated from each other by geography and time.

Founders and artists should be aware of where the technology is today. If you can help it, don’t play yesterday’s game. Let your intellectual curiosity guide you toward your joy and also the new edge of the fractal. Not looking backward.

Move your own skills and your own way of looking to the present and future, not to expecting a continuation of the past.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.