The “Passion Economy”, as coined by Li Jin, makes it easier for people to monetize their individuality through unique, creative work. This gives creators a feeling of autonomy, intrinsic satisfaction, and opens new markets.

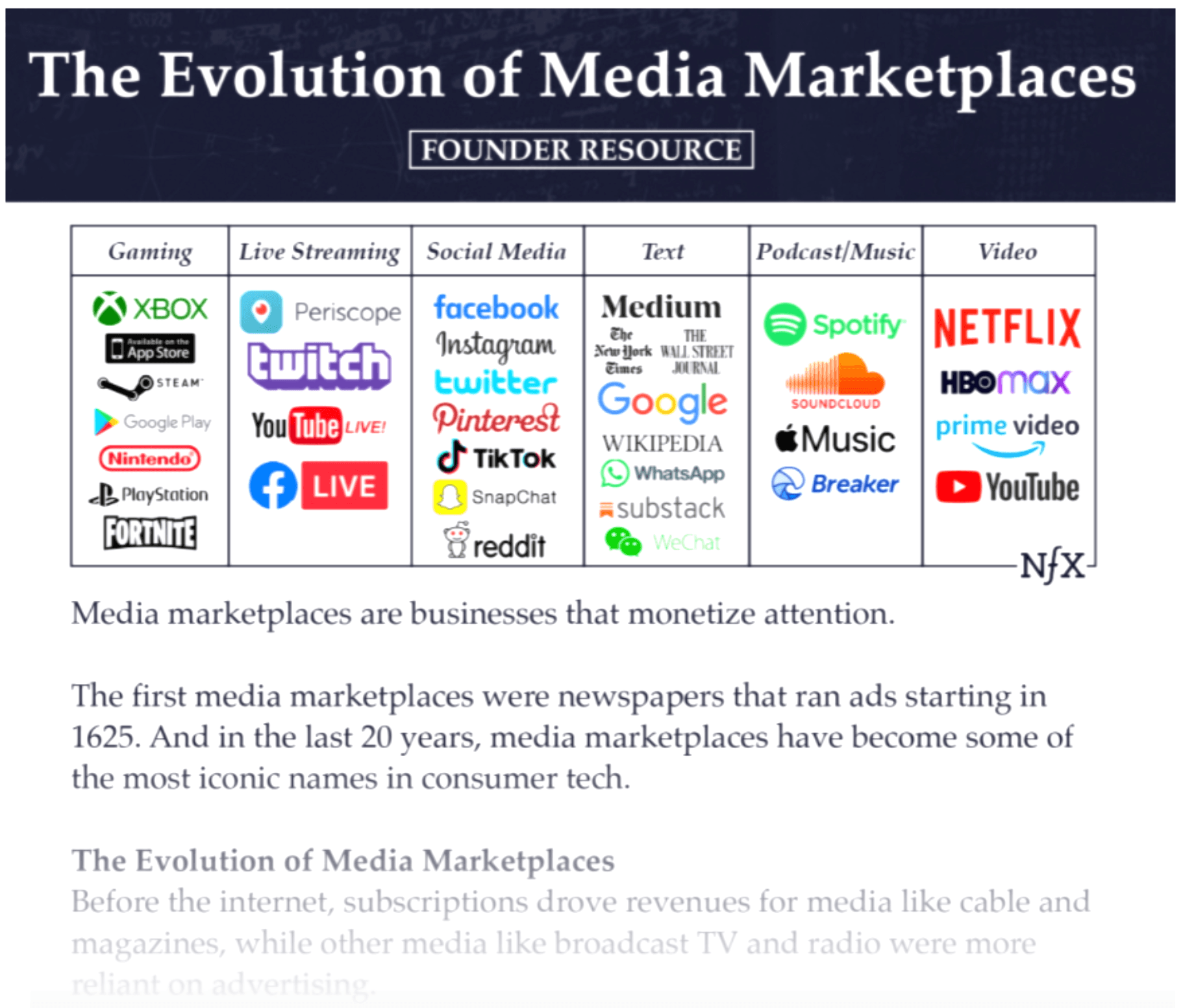

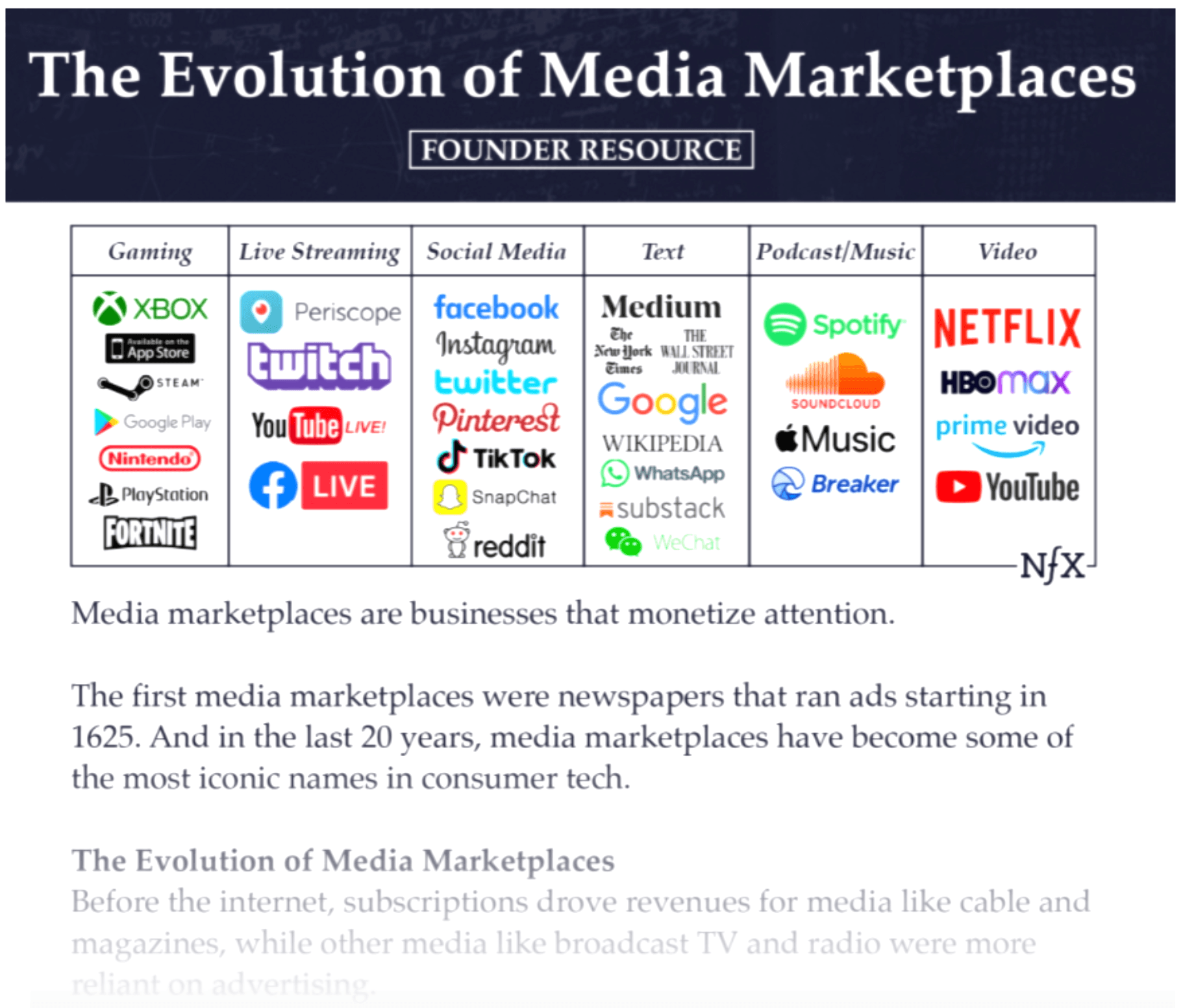

But an unseen challenge is this: “Attention” is the powerful currency underpinning the creator economy, but our current market for attention is rudimentary. Attention has a massive power-law problem. It’s typically mispriced. And, as you are increasingly conflated with the thing you create, you actually become the product. Despite drawbacks, it’s clear that the ability to get attention is the rewardable talent of today’s age.

To work through this and more, I’m joined by Li Jin, former investment partner at A16Z, now Founder and Managing Partner at Atelier (we’re investors). We discuss how NFTs are changing the economics of the Creator Economy, what happens when everyone has to be a marketer, and we look for ways to make platform participants into platform owners.

Highlights from our recent NFX conversation, below:

On Monetizing Individuality

- When I talk about the passion economy, I’m referring to technology platforms that make it easier for people to monetize individuality and to earn income through work that feels more fulfilling, and more meaningful, and creative.

- I was often online during my childhood doing a lot of the things (building websites, spending time writing fan fiction, participating in online communities) that are now actually considered jobs — but they weren’t then. Now, these are things that people can do and earn money from.

- It used to seem to me that there was this binary choice between: do you pursue your passions, or do you go for a practical career and decide to major in something that’s actually useful?

- James: It seemed like such a stark decision. It felt like with the internet touching everything and multiplying everything, it should be possible to solve that problem.

- Yes, I think the internet uniquely unlocks this opportunity for the next generation and all subsequent generations.

- This is different from just “be your own boss.” You can do that in the gig economy. But with a gig, you’re doing really rote commoditized, kind of repetitive work, where the platform is telling you exactly what to do.

- Whereas in the passion economy, workers are deciding for themselves the types of services and products they want to offer.

The New Way To Scale Your Earnings

- In the gig economy: To earn more, you just have to do more gigs, do more work, put in more hours, take on an additional task…

- In the passion economy: it’s much more about growing your audience or intensifying the relationship that you have with your audience and your customers. It’s about building a depth of fandom.

- So like with Patreon. Let’s say 4 months ago you had five people subscribing or being a patron to your stuff, but now you have a thousand people, and so you’ve scaled it up, but you still only had to make one video to earn more. So it’s a sort of scaling factor.

1000 True Fans >>> 1 True Fan (The Story Of The $25k NFT)

- Here’s another change in the scaling factor. There are new types of products that creators can offer that allow you to scale yourself in completely new ways, and allow you to price discriminate among your audience as well so that you don’t need to just scale your reach and reach more people.

- James: You can monetize your super fans to a higher degree such that you don’t need to become widely mega-famous if you can be deeply, vertically famous.

- An example is NFTs and how they enable creators to do price discovery in a really powerful way.

- For instance, earlier last month, I sold my first ever NFT on a website called Foundation. It’s an NFT marketplace. I didn’t really know how much it would sell for. I set the reserve price for 1.5 ETH, which at the time was about, I think, maybe $3000 or something. I thought the reserve price was quite high. I was afraid that it wouldn’t sell. And it ended up selling for 13.37 ETH, which was about $25,000 at the time, now about $50,000.

- But that was just insane to me that there was someone out there who cared enough about me, supporting me, supporting my work, that they were willing to pay so much for this NFT.

- I’ve jokingly called that the one true fan model versus the famous Kevin Kelly “1000 true fans.”

- Something NFTs allow you to do is identify that one true super fan who is willing to pay a really high amount and allow a creator to earn a lot off of not that many followers.

- Not only can you identify them, but really you’re allowing them to identify themselves.

- And in this case, or this person who paid this, they were not paying that amount of money because they thought the artwork was going to give them some utility. They didn’t anticipate they would sell it for more. They were doing it because they were interested in supporting the person who was selling it and the work that they were doing.

NFTs And The Act Of Ownership

- He told me something really interesting, which was that he felt like purchasing this NFT was an act of activism. He said that for him, it was a form of sending a message to the public, as well as to me, that crypto can help be a solution to the creator middle-class problem.

- That crypto can and should be used as a way to build up the creator middle-class.

- And so it was really important for him to own this NFT because he wanted to communicate through his act of ownership. Right now we’re actually in the process of talking about how to leverage this NFT to fund more artists. His idea was that we start a decentralized grant-giving organization to fund emerging artists.

- And so, we are early on in this NFT boom, which has been in the works now for three years, but really just took off in the last five months.

- These sorts of acts can have a little more impact and they will in a few years when this is more commonplace. But it’s interesting that transactions in this passion economy are perceived as activism or social statements.

“Purchasing attention”

- Zooming out from just this one example, I think broadly speaking right now the coverage of NFTs just looks like purchasing art and investing in art.

- I think that misses the mark.

- It’s definitely true, some of it, but I think it’s really just scratching the surface of what people are trying to accomplish when they purchase.

- I think there are NFT sales that function as relationship building. In this case, I formed a relationship with this buyer. We’re still talking about how to fund emerging creators, we’re thinking about setting up this decentralized organization to do it. So there’s that element.

- But I also think it’s a way to capture the attention of a popular creator, in a world in which the creator is constantly being bombarded.

- This is a way to dial up the volume of your message in a way.

- It’s a role reversal from the creator just constantly marketing to the consumer.

Flipping The Economic Transaction

- Let’s think about the ‘like button” economy. My friend Patrick Rivera says “All likes are fungible.” Everyone’s like counts the same. Doesn’t matter who you are, it’s an equal point of 1 like.

- I think NFTs are a form of a non-fungible like.

- James: This seems like an indication that perhaps we have a very immature attention economy where this person was willing to spend $25,000 to get your attention, and that we are undervaluing attention dramatically, and that over the next few years, maybe that is going to get priced in and fixed?

- When people typically talk about the attention economy, they’re referring to creators amassing the attention of an audience, and then, after they have the attention, they’re able to monetize that attention in all sorts of different ways.

- I think what’s really interesting about NFTs and some of the new creator economy products that are coming into existence, is that they’re reversing that relationship and they’re kind of switching… They’re flipping the economic transaction. Changing the direction that the attention is flowing and the way that the money is flowing.

- And what I mean by that is, the audience member is purchasing attention from someone that they admire in the case of an NFT sale.

- James: We’ve always had creators purchasing attention of consumers… it’s advertising! But much more rare to have the consumers now (the fans) purchasing the attention of the creators.

- In the case of a cameo sale, a cameo purchase, I think of the fan of that celebrity as purchasing their attention for a brief moment in time as well.

- Same with the tipping behavior that you see on OnlyFans, which drives a ton of their GMV. People are sending large tips to creators as a way to get their attention.

- There’s all this attention going around and it’s going to get increasingly monetized in all directions now because we can measure it in the digital realm.

- And attention has become such a scarce thing to capture that people are willing to pay for it.

Attention Is The Rewardable Talent For The Current Era

- James: We have a person who was really good at getting attention through Twitter — and then he ended up being President. In the future world, marketers are the winners?

- This relates to an amazing post that Packy McCormack just put the other day called The Great Online Game, where he describes how we are all participants in this huge, massive, multiplayer online game.

- But not in the traditional sense of an online game, rather this game spans the entire web, it spans the entire world, it bridges to the offline world.

- Our performance in this online game of Twitter, and social media, and blogging, etc, it bleeds into the opportunities that we have for making income, progressing in our careers, networking, and connecting with people.

- And I think we’re now in a world where you do have to play this game, you don’t have an option anymore. I think the notion that you could have one job forever and it could be pretty secure as long as you just did a good job in that position, I feel like those days are over in America.

- So you do have to play the game and part of the game is being a good marketer. It’s happening regardless of whether or not we like it.

- James: What I think we’re saying here is that perhaps writing, or marketing, or figuring out how to get more attention is the rewardable talent for the current age and going forward.

- I think being good at memes is part of that. Being able to generate memes, and memefy things and get them to take off, I think that is a really prized skill set in today’s day and age.

- I feel like this is a skill that is really native to gen Z and all of the creators that I see on TikTok. It’s all very second nature to them to remix others’ work, and duet them, and collaborate on videos together. And that entire platform is like a huge generator on a daily basis of so many memes. And they’re constantly trying to make their videos viral and take off. So I feel like that generation in its entirety is very good at it.

Passion Economy Thoughts On Substack

- There are a ton of people who love to write, there are a ton of people who have interesting pockets of knowledge and expertise that can be shared with the world

- To date, on the internet, the way to monetize, if you are a great writer is either 1) through putting ads on your blog — or 2) run a Substack.

- I think Substack did a lot to pioneer the subscription model of newsletters. But I think those two models leave a lot of writers still without a great business model.

- And those writers left without a great business model are perhaps publishing at a lower frequency, at a lower cadence

- James: Well, Substack is really subject to the same power-law challenges at a place like YouTube and Twitter, right? Just a few make a ton and almost everybody else makes nothing?

- That’s a symptom of how discovery works on the internet, which is that it’s driven by these algorithmic discovery platforms, the social platforms, and those discovery platforms determine what readers are able to find in terms of writers.

- So I don’t think that’s necessarily a challenge with the business model itself, but really with how attention is directed and allocated.

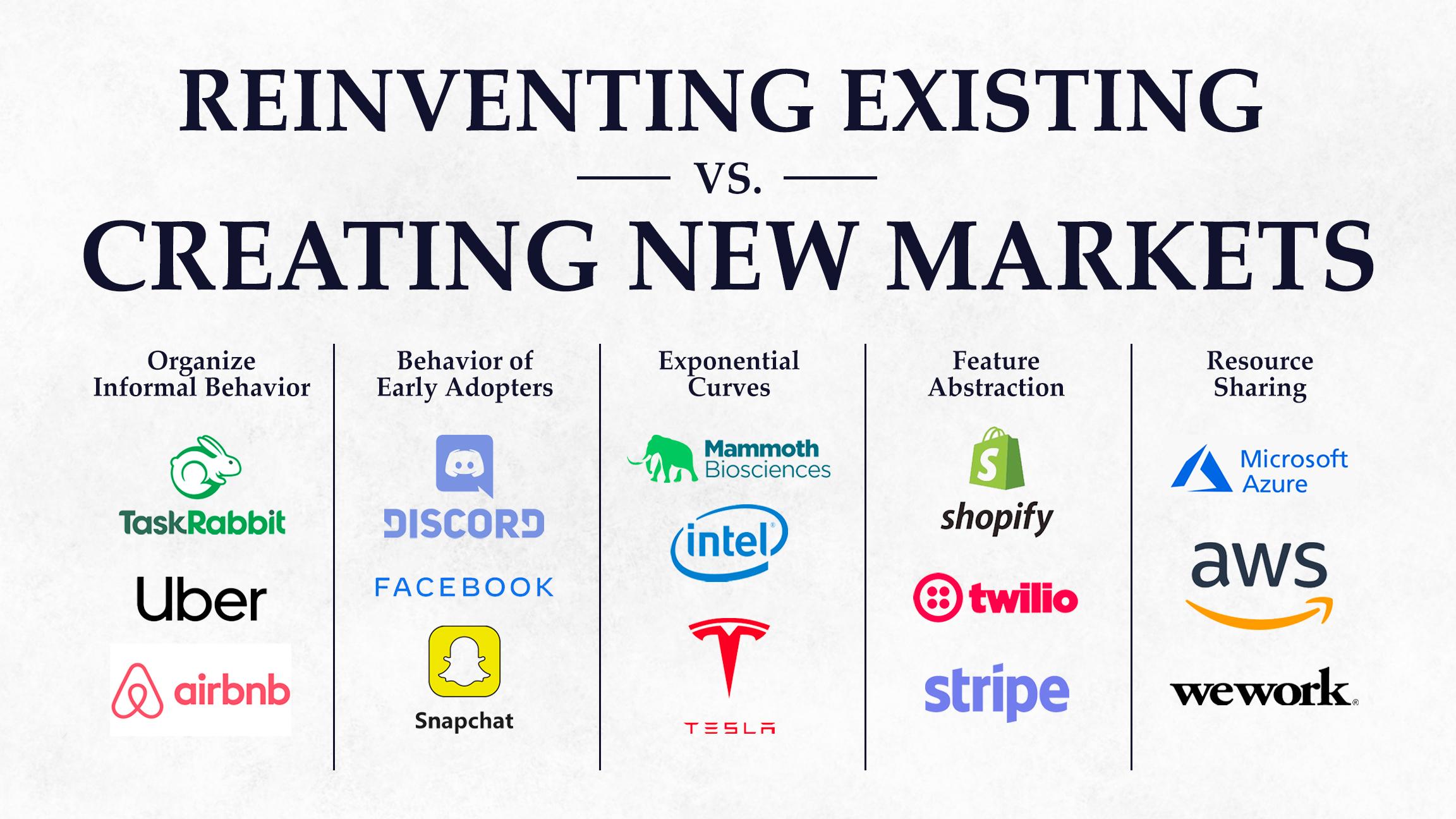

Success Key #1: Market Creation

- When I look at promising passion economy startups… What I’m really interested in is companies that are inviting new participants into types of creative work that had been previously inaccessible to people.

- So they’re enfranchising a new segment of the population to do some type of work that hadn’t really been easy or available to them before.

- In the Mirror case, that was writers who aren’t publishing frequently.

- In the Maven case, that’s experts who didn’t really have a way to share that expertise and monetize it with the world.

- But for these companies and for many others, they’re creating the entire toolbox that a person would need to convert their skills, or their interests, or their passions into a product, or a service that can be easily offered and create a great consumer experience at the end of the day.

- So you’re taking people from zero to one, from, “I’m not making any money,” to, “I’m making some money.”

- And it’s interesting because a lot of people make businesses to compete with tools where people are already making money. I know in marketplaces, we often see people design marketplaces to try to intermediate or digitize transactions that are already happening.

- But the big mental breakthrough is to say, “Can we create something that creates new transactions that aren’t happening at all?”

- When you do, you have incredibly loyal people to your platform because you’ve taken them from nothing to something.

- Market development. You’re taking people who previously had not been productive in this way before and enabling them to participate in this new type of work that hadn’t been available. So it’s creating a new market where previously the market had been much smaller or didn’t exist.

- And for me, personally, I think that’s just a lot more exciting as an investor and as a person in this world than just intermediating a relationship that hadn’t already existed.

- And I think it’s also emblematic of the huge shift that’s happening in work in this country. I think we’re moving from this world in which people just had a job at a company, to a world in which more people are self-employed and pursuing work with greater degrees of autonomy and self-direction.

- And if that’s the case, then what you really want to do is enable these new participants to be able to work in new ways, not just intermediating an existing transaction.

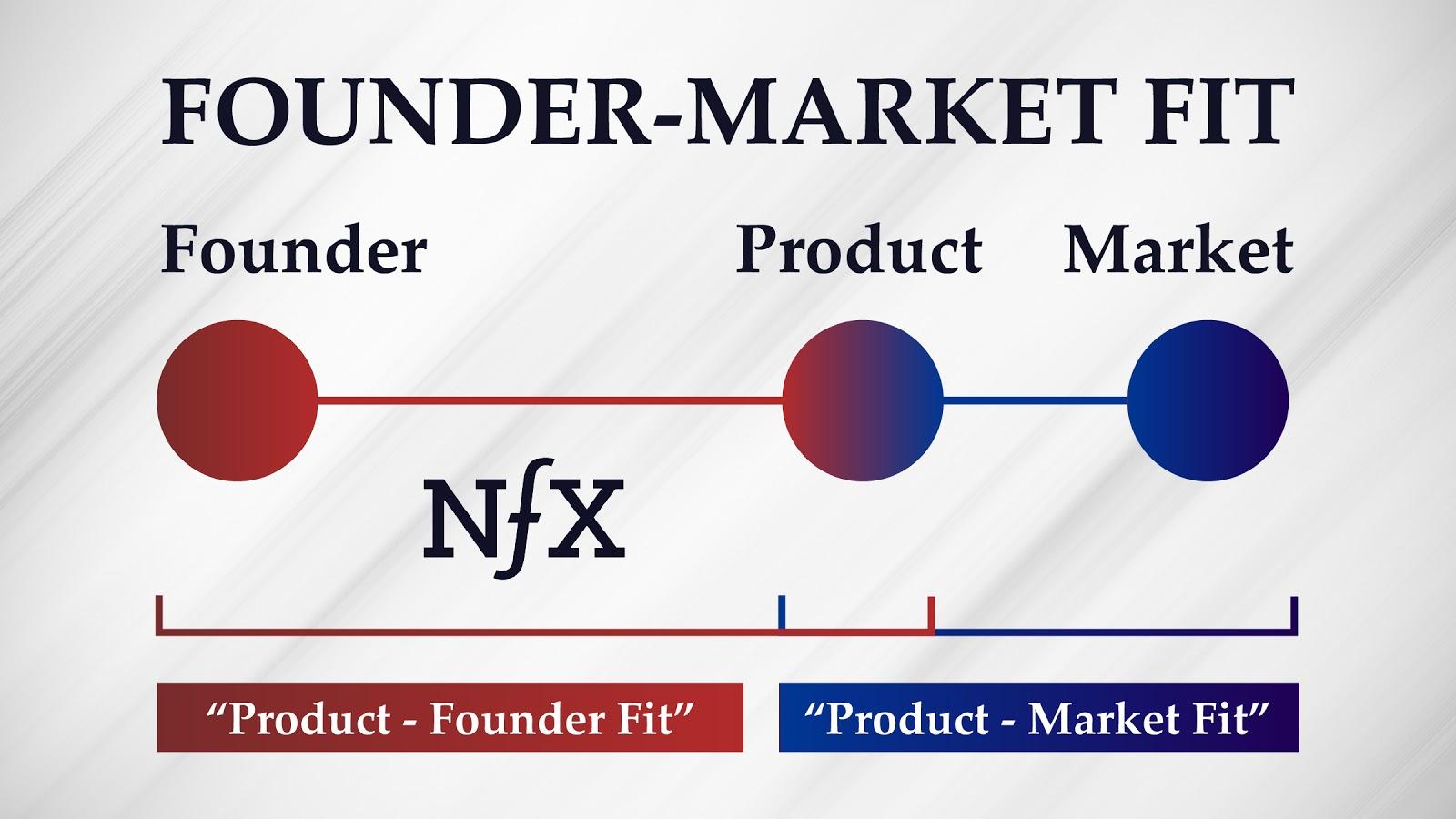

Success Key #2: Founder-Market Fit

- I would say another key element to success building passion economy startups is founder-market fit. And I know you had this amazing blog post on it, on that topic, which I refer to often.

- But I think in the passion economy, the end-users, the creators, or solopreneurs, or whatever you want to call them, the users of these platforms, they’re sitting somewhere between a consumer and an enterprise. They’re like micro SMBs.

- And I think in the early days, if you’re running a creator platform for them to create on, the way that you acquire them is like hand-holding them, identifying them, talking to them one-on-one, cultivating their trust, getting them to try this completely new platform.

- And so it’s really important for the Founder of those startups to have great founder market fit, to have really deep customer empathy, to be like basically one of them – like Jack Conte at Patreon. Such that they’re able to earn the trust of those initial users, and get things going, and get traction on the platform.

- I get nervous when someone is building for a new type of work, but just does not have relationships with the types of people who would be using the platform or connectivity to those communities. Because I think those initial users, whether they’re writers, or experts, or teachers, or whatever, they’re making their decision to use this platform as a huge expression of trust in the Founder.

When You Are The Product

- I think in the passion economy, every individual creator is trying to offer a product and trying to find product-market fit for it, where the market is their target customer base and they themselves are the product.

- James: There’s going to be some heartbreak around this because if I put out a piece of work and you don’t like the work, that’s fine. But if I put myself out there and you don’t like me, that feels different.

- It’s like when you’re a Founder and you get rejected for fundraising, and it feels really personal because that company is so much an extension of yourself. I think creators go through that on a daily basis too.

- Because it’s about their individuality, it’s about the unique thing that’s going on with them. That’s the thing on market.

The Passion Economy Demands Creator-Format Fit

- I think it’s really important to find creator-content fit, or better yet, Creator-Format fit. It’s kind of the creator version of product-market fit.

- It’s determining what feels natural to you, what feels the most authentic, and comes the easiest to you?

- And I think it’s really important to find that because otherwise, you’re not going to enjoy creating that thing, and brand building in that way.

- For me, for example, writing comes really naturally. I love writing. It’s like it feels as natural to me as breathing and it helps me clarify my own thinking and I just really enjoy doing it.

- And so, for me, it’s just very natural to create in Substack and to publish that way. But if you had to ask me to brand-build on TikTok, I would absolutely suck at that, and not be able to get anywhere, and to not be able to build a brand at all, whereas that comes very naturally for other people.

Transparency Creates A Steep Power Law

- James: And so we’re back to the power-law problem. Which is that some people are very charismatic and other people just aren’t. Some people are really fast, and smart, and interesting to listen to and some people aren’t.

- James: And these attention systems we have today — and this identity of the individual with the work — these systems are not allowing for a middle-class.

- James: Li, you did this great article for HBR, listing 10 ways we might think about designing systems so that you can have a thicker middle of the power law, where there is some middle-class. It might be percentile 90 to 98 because the top 2% will do fine. But whether it could be the top 30% making an okay living, it’s not clear.

- It’s so pernicious, right? And the internet just makes it more pernicious. The example I keep using is, 30 years ago, if you wanted to sell your home, there were maybe 30 agents, but there was no listing for them, and you really had no information. So you just went to the one your neighbor told you about. And that person would get their fair share of listings, and make their fair share of money, and they would put food on the table. But now you can go online and instantly see all 30 agents in your town. And they have blogs and online ratings. You can easily see who the best agent is — and don’t you want to use the best agent? So the power law says all the business flows to that one or two.

- And so, the power law gets steeper in this case because of the transparency that the internet gives us.

The Power Law Of Life

- James: And that is affecting people everywhere, as they struggle to realize where they are in the power law of life. It’s not just getting clients. It’s putting out your songs on YouTube or TikTok, just for fun, and seeing all the people who are “better” than you are, and getting more attention and subscribers and comments.

- It feels to me that there’s frustration and anger. People are realizing where they really are, as the internet lets you visibly compare to quite literally everyone around you — and so we’re not having the illusion anymore like we used to, that we’re doing better than we really are. And it’s painful.

- It relates to that piece about the great online game because we are now all having to compete with each other in this online arena and it’s no longer the case that you just have to be the local best at something — or even locally, just decent, in order to make a living.

- You now have to be like one of the best people in the world in a certain niche in order to be successful. Because to your point, now as consumers, we can go online and choose the best, and do our research, and find the best possible provider for anything. And that means everyone who’s not the best ends up losing out.

- The cat’s out of the bag now and we just aren’t going to go back to this world in which we had local monopolies on different types of services, and everyone can make a decent middle-class income just by being okay at something.

- That era is over for better or worse, and there’s going to be beneficiaries of it, and there’s going to be people who lose out because of this.

- And I’m not sure what that means for society and what we should do collectively as a society. I think there’s been a lot of discussions that we should continue to have about universal basic income and how we can support the folks that maybe just don’t have the skillset to be able to succeed. Or the skills that they once had that were useful just are no longer the case anymore.

- James: We should also distinguish between actually doing well and feeling like you’re doing well. Because people might be earning enough to have an okay standard of living — but if they’re constantly bombarded with this feeling of inadequacy, that the overall Internet throws at them, then despite doing okay or doing better than their parents did, they won’t feel that way, and that will cause social unrest, and that will cause misery.

- This is a challenge in designing systems to help people feel smart, to feel successful, to feel connected, to feel loved or appreciated, or to get some attention, to feel like they have somebody listening to them.

Web 3 & When Platform Participants Become Platform Owners

- I’m really excited about Web 3 and what comes after all of our current centralized platforms and companies. I’m exploring the intersection of Web 2 and Web 3, and companies that are trying to build bridges between the two. And are we there yet?

- I think perhaps the state of the world that we get to is never going to be fully one or the other, but there’s going to be probably a mix of services that make sense as Web 2 companies and then other companies that make more sense as completely decentralized services.

- And that’s really the definition that we’re using to apply to Web 3.0, here, is this decentralization. Decentralized applications and services that run on the blockchain.

- James: What are people not seeing clearly about that, yet?

- There’s probably too much emphasis on the trustless nature and also being uncensorable. I think most people are actually very trusting and don’t mind trusting a third party, and I think also most people probably aren’t saying things that would need to be censored or removed from these centralized services.

- Obviously, there are notable exceptions to that, but for the most part, people aren’t worried that Twitter is going to deplatform them or suspend their account, and not allow them to use the platform at all.

- I think what’s more interesting about Web 3 and the angle that I would love to explore more is, in so far as it serves as a vector for allowing platform participants to become the owners of the platforms themselves.

- So as a way of distributing ownership to the broader ecosystem, rather than just a small group of investors and employees of the company.

- The ownership economy sort of thing where we’re going to have many more ways for people to participate in ownership of the real estate, or the companies, or the platforms, or the art that they’re involved with.

- It just makes logical sense. It’s the next natural evolution.

- I think as we move away from traditional employment, to this world in which people are utilizing a variety of different tools and services to create their own businesses, those individuals who are utilizing those platforms and services, they’re just as meaningful to making that platform valuable as the employees who are doing the engineering full time at that company.

- I think of Patreon equally being built by all of the creators who decided to use Patreon, especially in the early days as it was the work of one single company and the employees that work there. So I’m really interested in how we can involve all of the platform participants as co-owners and stakeholders in these platforms.

- James: And we’re going to end up seeing the development of some standards and benchmarks around that too, because it’s unclear where the line should be drawn, right? I mean, iOS is trying to take 30% of all the revenue on their platform.

- Is that the right number? Should it be 10%? Should it be 20%? Should it be variable? And we still haven’t come to the conclusion of that, but that’s been pretty stable for about a decade, and it’ll be interesting to see what percentage of these entities get shared with the contributors or if it’s going to be super variable along with the power law.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.