See below for the audio version of this essay read by James Currier.

We work with a lot of Founders who have prior startup experience — either as Repeat Founders, or team leaders from successful high-growth companies.

They come to us knowing they want to start a company, but they are still in the process of coming up with their new startup idea.

This is not as easy as it often sounds in the telling after the fact. Successful entrepreneurs rarely tell the story of the first few months where they battled to find a good idea. In reality, most top founders go through a rigorous ideation process to come up with the idea we know them for today.

It’s often said that success is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration. In other words, 1% of success comes from the idea and 99% comes from execution.

We disagree.

This might be true at later stages, but at the initial stage of a startup, the core idea makes a huge difference. Small changes in your initial idea/direction will make a big difference to where you end up.

With a great idea, it’s a multiplier for all your efforts down the line, compounding over time. Going in the wrong direction wastes your life’s energies.

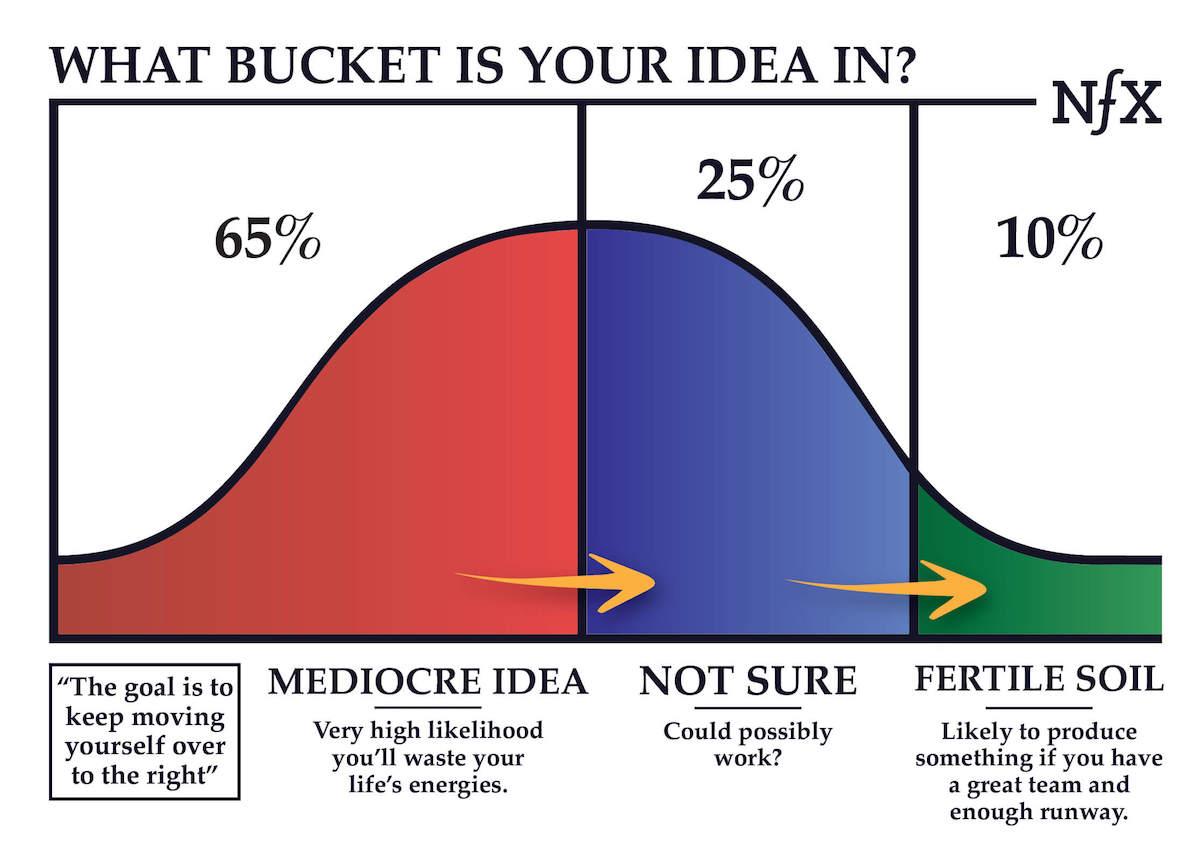

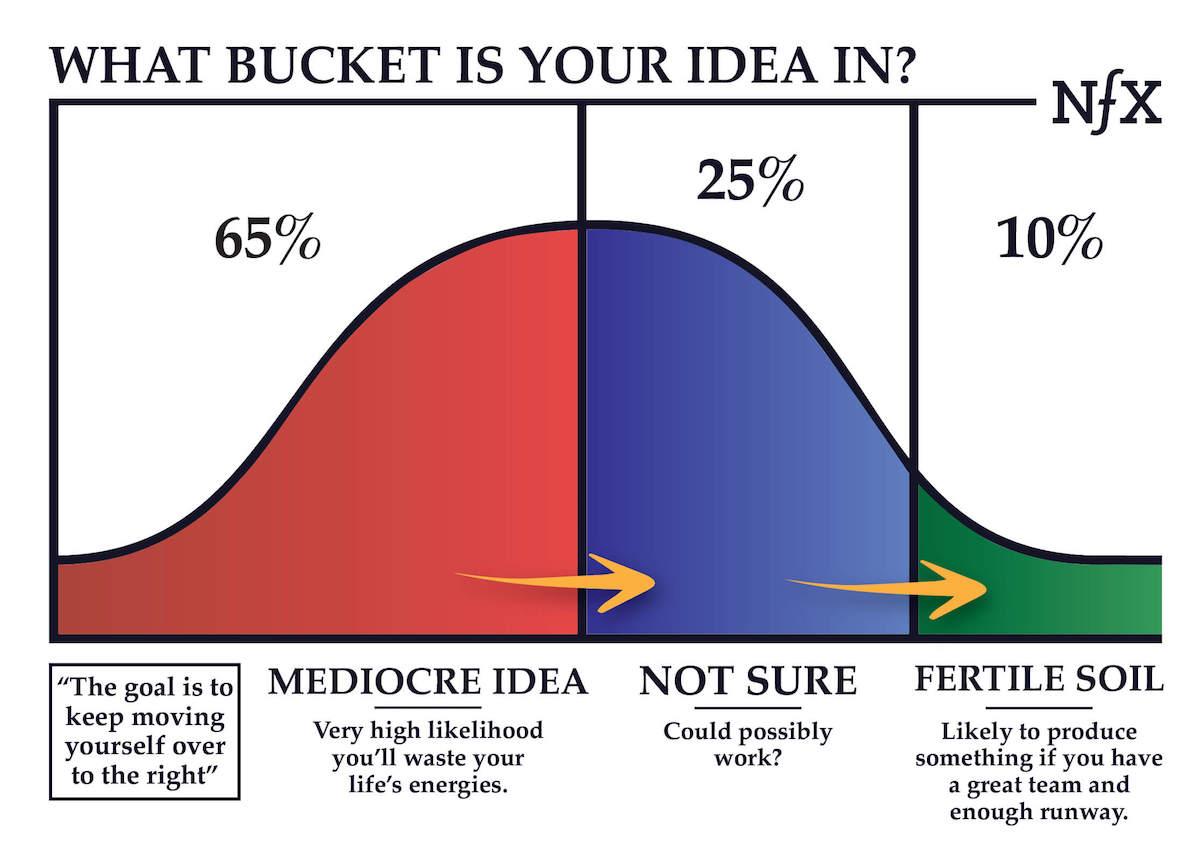

In fact, we believe the biggest waste in our startup/VC ecosystem is great people working on mediocre ideas.

Note that it’s just as hard to build a mediocre company as a transformative one. Both will take 100% of your time. So you might as well work on a bigger idea.

As Founders who started >10 companies that exited for >$10 Billion, we feel a responsibility to share what we discovered about great startup ideas with other Founders so you’re not wasting your life energy on a mediocre idea.

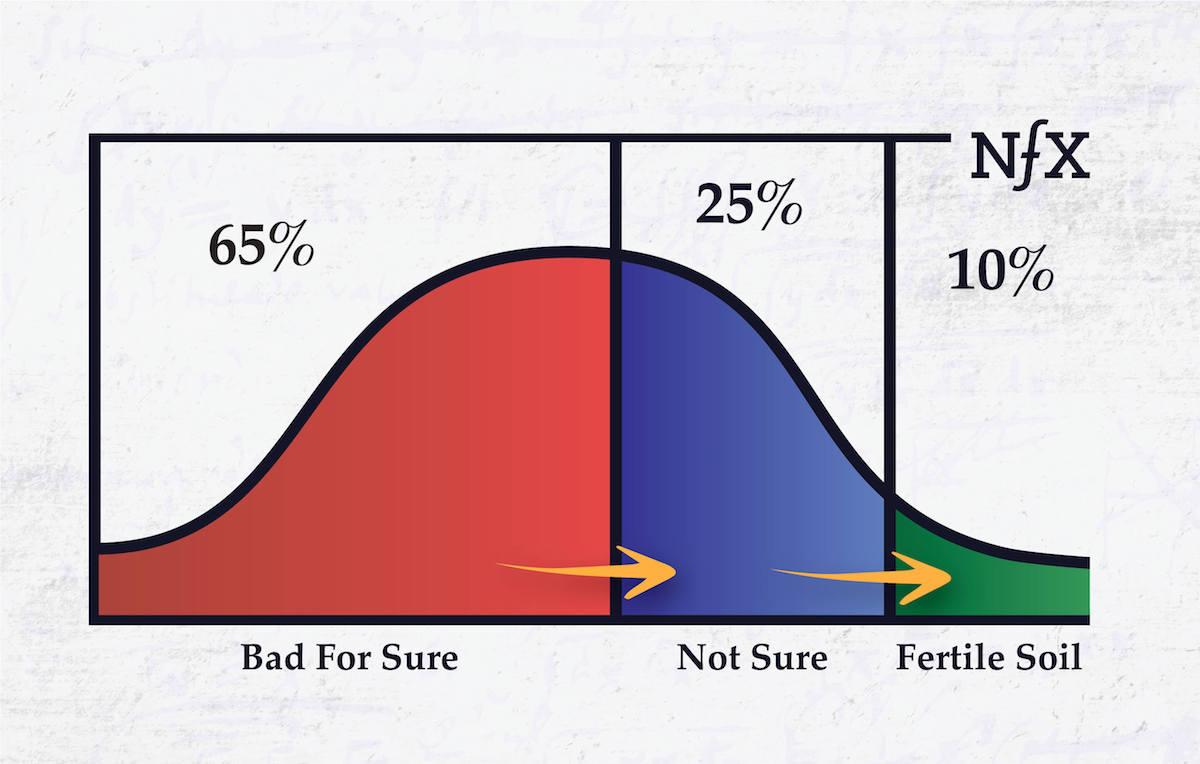

We’ve identified a total of 15 frameworks to help Founders refine their startup ideas and move from left to right, and today we’ll share 5 of them.

Note: if you want access to all 15 frameworks, sign up here. We are building a private, invite-only community of Founders who want to get access to the underlying frameworks of great startup ideas.

Framework 1: Innovate Just Enough

As an innovator it’s tempting to come up with something 100% original. But the truth is that nothing is 100% original, and the more you strike out on your own path, the less you know where it’s headed. It feels glorious to go all-in on something crazy, but…

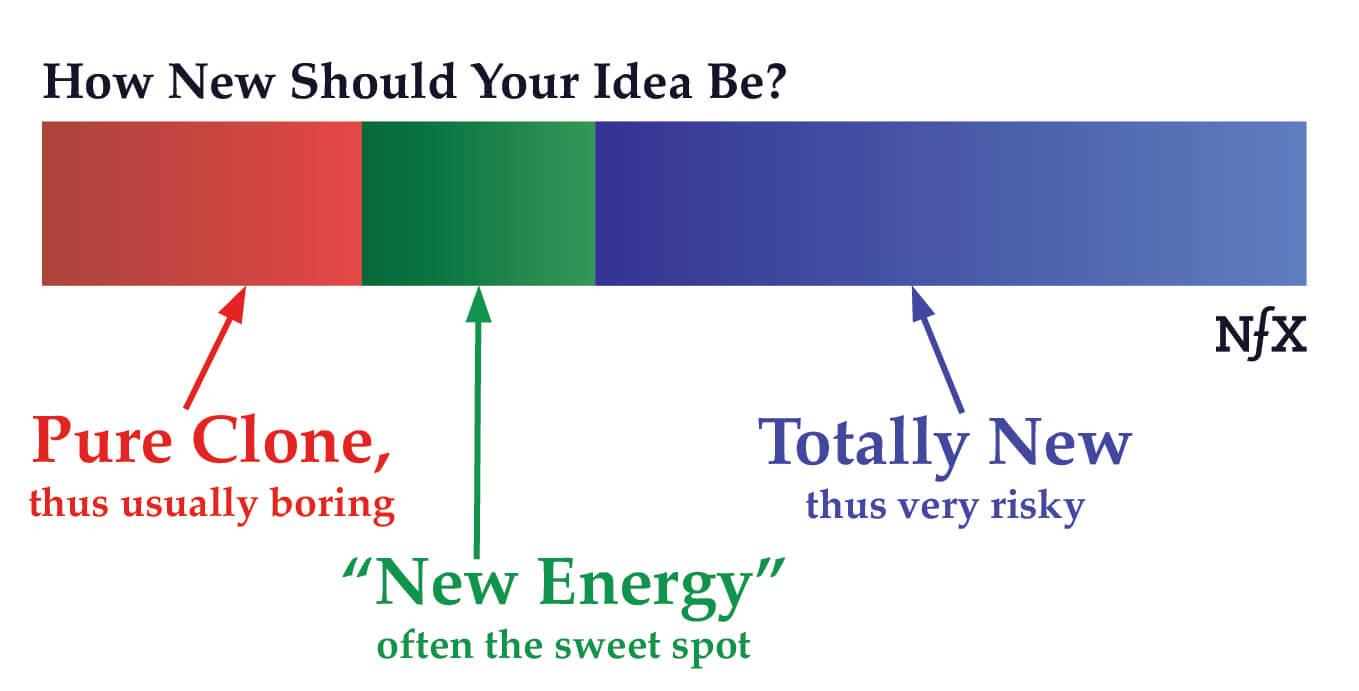

Novelty is a risk. Too much of it, and you’re almost certain to fail. But too little of it and you’re just a redundant copy of someone else — which is also a recipe for failure. What’s needed is a balance of both.

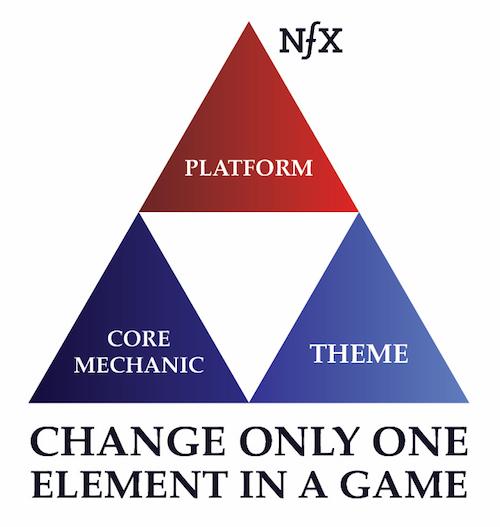

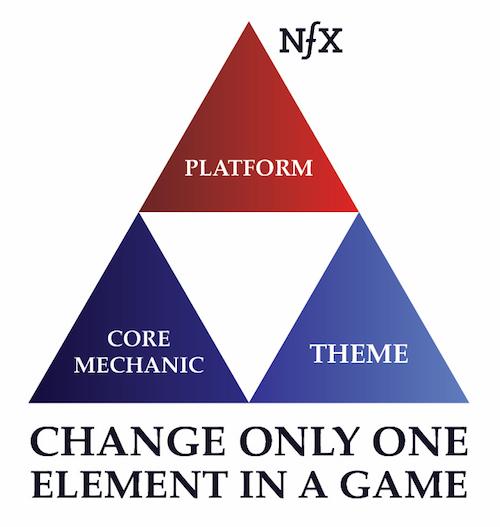

One way to strike that balance is to apply a framework that we learned from the gaming industry: when making a new game, change only one element from what came before. In gaming, there are three big elements:

- Platform – P.C., internet, mobile, Facebook, console, etc.

- Core Mechanic – e.g. build and conquest, slots, collecting, first-person shooter, etc.

- Theme – Dragons, Atlantis, Pirates, Vikings, Space, Vampires, Mafia, etc.

Perhaps changing only one of these three helps you focus. Don’t overstretch. Don’t try to change everything. Be aware of what parts of your idea you’re testing that are new, and what parts of your idea you can count on working.

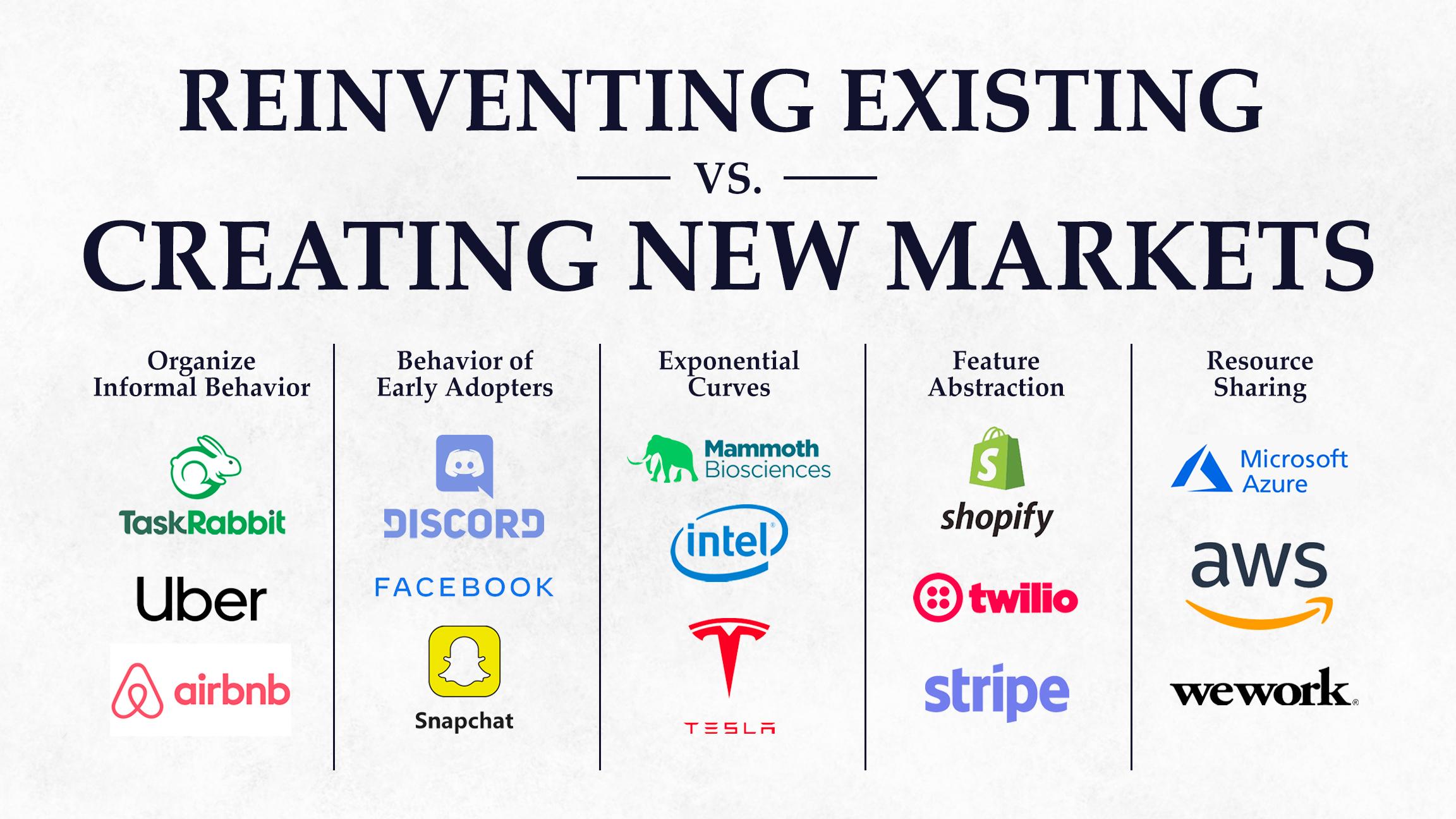

The biggest ideas often strike a balance between what has been proven to work and something totally new. Iteration can be a form of innovation. Most of the companies you admire as innovative actually operate in the “New Energy” category.

Framework 2: Leverage Technological Shifts

Without a big tech shift underlying your idea, it’s less likely to be a breakout hit. Enabling technologies matter in timing your startup idea. Can you identify what technology has changed in the last 3-36 months that will let you create a new product? A new experience?

Examples to spur your thinking:

- Ride-hailing: Paying for taxis was commonplace, but the advent of the smartphone allowed SideCar, Lyft, and Uber to show you a car coming to you on a map in real time after you ordered it with the tap of a button. It also allowed frictionless, instantaneous, in-app payment so that you didn’t have to get out cash or a credit card.

- Wealth management: The very wealthy have always been able to afford to pay people to manage and invest their savings, but financial APIs in the late aughts let Wealthfront extend a similar service to people with a ~$10K net worth instead of ~$5M.

- Video sharing: Video-hosting has been around for a long time, but broadband penetration in 2007 set the stage for YouTube’s breakout success. Before that, YouTube wouldn’t have been viable.

Look for a new product experience in proven areas that is only possible recently due to a recent technological shift.

Framework 3: Take More Risks

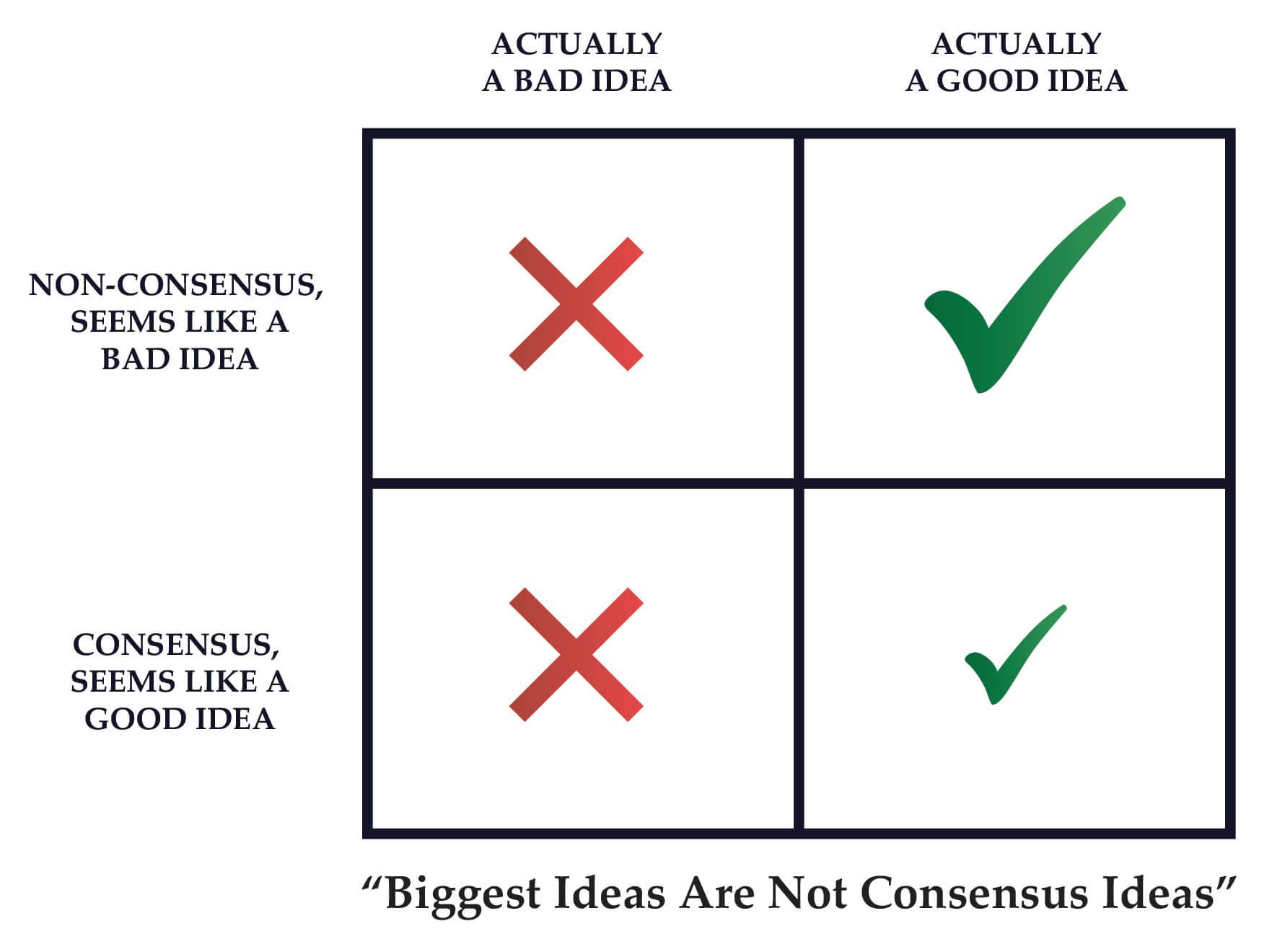

This is a framework that originally came from Howard Marks of Oaktree, which I learned via Andy Rachleff of Wealthfront. Marks realized that many of the biggest ideas both identified some new truth while at the same time being non-consensus ideas, meaning most people didn’t think they looked like good ideas at the beginning.

Such contrarian ideas allow you to compete in a less crowded market, and thus they give you a greater ability to take market share and win before others catch on. This is particularly helpful in network effect businesses and in consumer businesses. Doing something that looks “stupid,” or “like a toy” can turn out to be prescient. Test your ideas against this framework.

Framework 4: Solving a Problem vs. Creating Opportunity

If you were making a pitch deck for Facebook, SuperCell, or Slack, could you have convincingly articulated a “problem” that you’re trying to solve? Not easily. However, you could have easily framed the idea as: “This would be awesome.”

Many investors say that *all* pitch decks need to articulate the problem. We don’t agree. Many great companies can’t be — and weren’t — conceived that way.

When evaluating ideas, you should certainly think about how much they are solving a clear problem. But also think about what new opportunities they might be creating. Your conceptualization of the business will be very different depending on how much of each you have.

Framework 5: Market Risk vs. Execution Risk

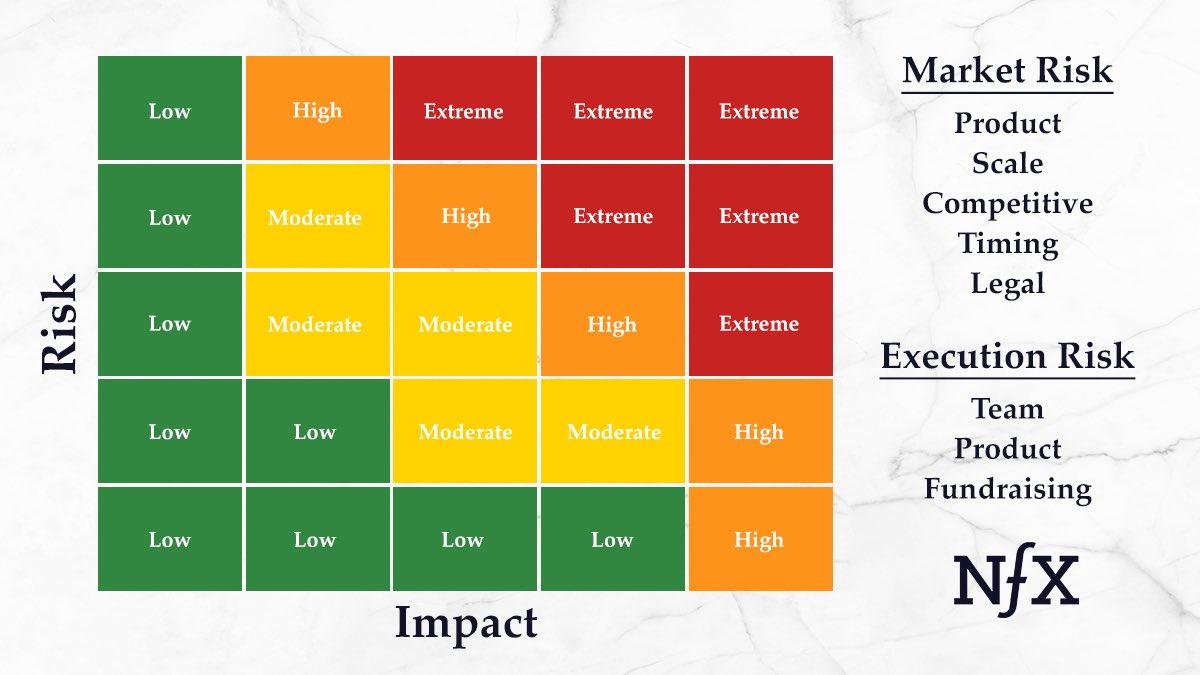

Market risk is when you don’t know if anyone will want what you are building. Execution risk is when you don’t know if you can execute at a world-class level on the idea.

Twitter is an example of a successful company that took on market risk. Would people really want to broadcast 140 characters to whoever happened to be listening? It turned out they did, but even after Twitter found a market, they still had to deal with execution risk. Could they keep the site up at such scale? They barely managed it, so it happened to work out.

SpaceX is an example of a company that took almost no market risk. Elon Musk knew that there were many potential clients who would want to buy trips to space for satellites, etc. Rather, SpaceX took on a huge amount of execution risk — could a small team with only a few hundred million dollars in financing actually send payloads to space?

Second-time founders and their investors often have more confidence in the Founders’ ability to execute, so they are willing to face down incumbents and competition in a proven market, betting on their ability to execute better than existing players. These ideas carry clear execution risk and less market risk up front.

An example of second-time founders going after “execution risk-only” opportunities are things like the new “full stack” companies taking established businesses head on: Lemonade in insurance, Honor in home nursing, Compass in residential real estate brokerage, etc.

First-time founders often need to avoid incumbents and direct competition in order to get going, and thus target unusual, non-consensus ideas. They’re likely to take on more market risk initially as a result. But companies with initial market risk will eventually face execution risk as well at a later stage.

Evaluate your ideas to see how much of each of these two risks it takes on and which you are better suited to solve.

Get Aimed in the Right Direction

“Small differences in initial state yield widely different outcomes.” – Chaos Theory

We’ll be writing more about startup ideas in the coming months, but our hope is that the frameworks we shared here will help both veteran and first-time Founders navigate their idea space, even if we can’t work with them directly. Guidance, insight, and pattern recognition from VCs was always helpful to us in our own journeys as Founders, and we’d like to pay it forward.

NFX has 7 more frameworks that we use to help founders navigate toward better ideas, both before they launch as well as when they’re already in flight. We’re creating a group of top Founders to discuss these frameworks in small, private forums so we can work with Founders directly in order to find ideas that best fit both them and the market. To get more articles like this and to join the forum, apply here.