Seeing things in ways others do not — at top speed, and with confidence — is the biggest advantage we know in the “mental game” of startups. And the good news is: this advantage is learnable through mental models.

We previously published Part I of our mental models for startups, covering decision-making, culture, market disruption, KPIs and more. Today, we are releasing Part II of our collection, focusing on fast-acting mental models for:

If mental models are how we understand the world, then applying mental models to our startups is how we can change the world.

Idea Generation

Coming up with a new startup idea is not as easy as it often sounds in the telling after the fact. Successful Founders rarely tell the story of the first few months when they battled to find a good idea.

In reality, most top Founders go through a rigorous ideation process to come up with the idea we know them for today. Here are 8 mental models for improving your own ideation process.

1. Flexible Curiosity

“Be prepared to stretch what interests you.”

Founders who only want to do one thing usually end up failing. Inevitably what ends up working is a little different than what they thought. Founders must have flexible passion — they can’t be tied down to a single, immovable set of tactics.

Most startups have to learn and adapt. You’ll likely end up serving a different customer, in a different geography, in a different way than you thought.

Learn to expand your curiosity and acquire new interests. Become interested in payments, not collaboration software (for example). This is a mental leap you’ll likely have to take at some point as a Founder.

2. Idea Chaos

“Small differences in initial state yield widely different outcomes.” – Chaos Theory

Chaos Theory is a branch of mathematics that focuses on dynamic systems — such as startups — with apparently random irregularities which are actually governed by underlying patterns.

Critically, in startups and Chaos Theory, the underlying patterns are highly sensitive to initial conditions — ideas in the case of startups. That’s why small changes in your initial idea or direction will make a big difference to where you end up.

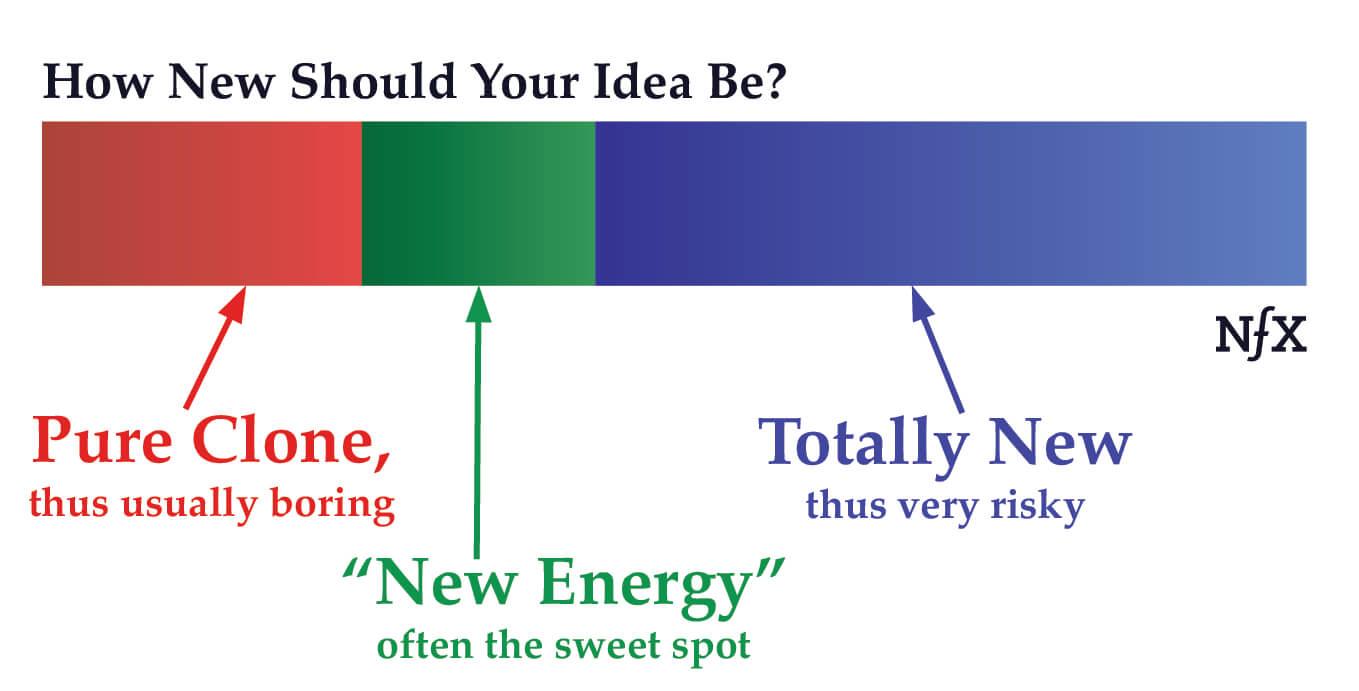

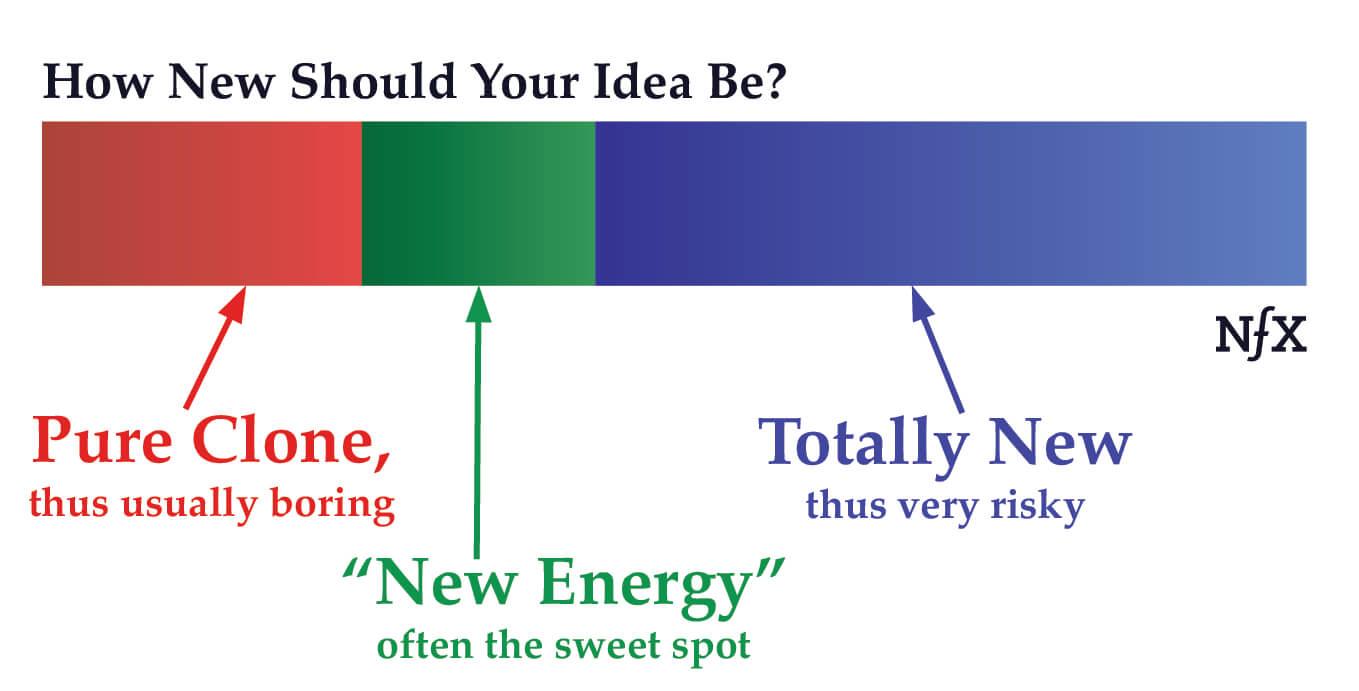

3. New Energy

“The biggest ideas often strike a balance between what has been proven to work and something totally new.”

Iteration can be a form of innovation. Most of the companies you admire as innovative actually operate in the “New Energy” category.

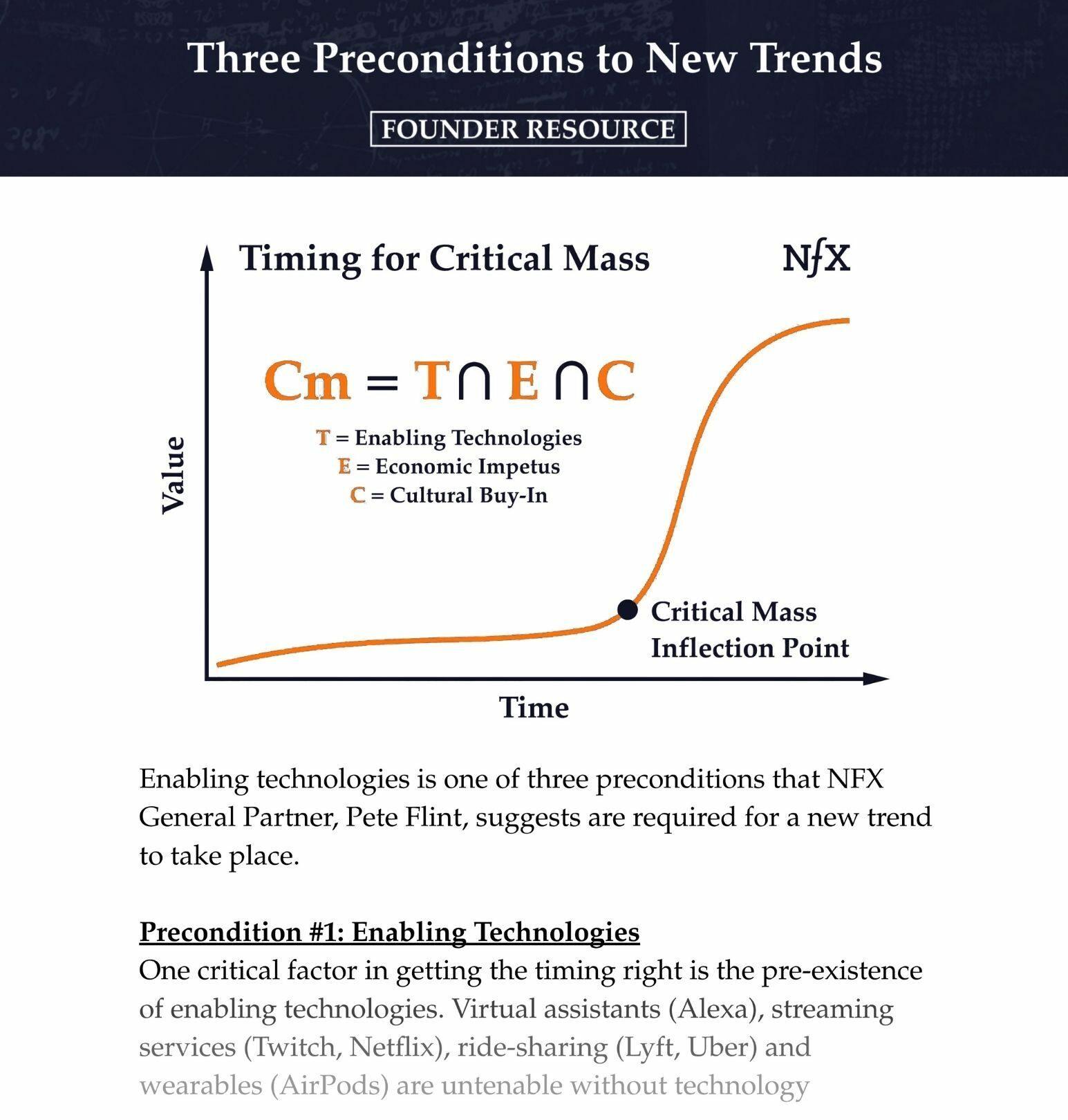

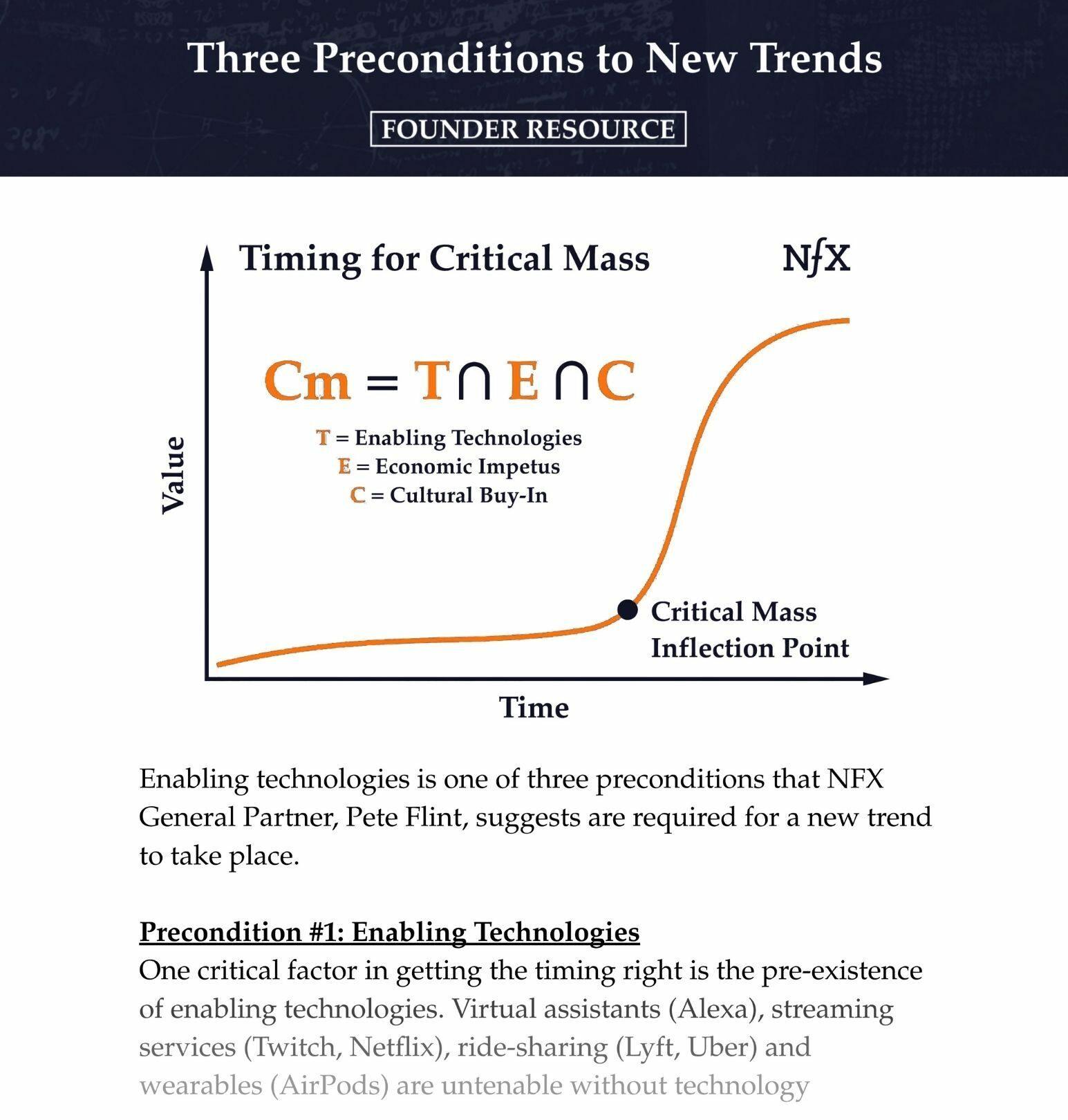

4. Leverage Technological Shifts

“Look for a new product experience in proven areas that is only possible recently due to a recent technological shift.”

Without a big tech shift underlying your idea, it’s less likely to be a breakout hit. Enabling technologies matter in timing your startup idea. Can you identify what technology has changed in the last 3-36 months that will let you create a new product? A new experience?

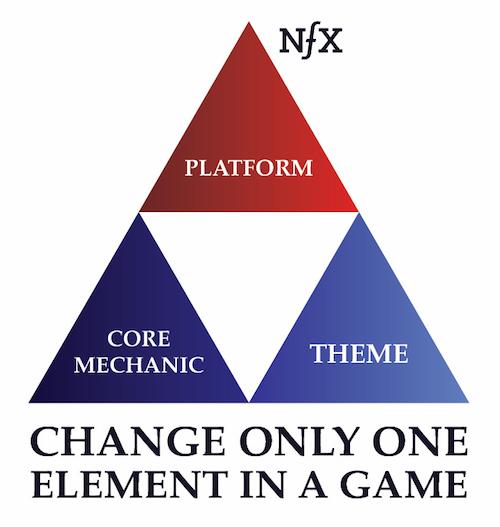

5. Innovate Just Enough

“Too much novelty and you’re almost certain to fail. But too little of it and you’re just a redundant copy. What’s needed is a balance of both.”

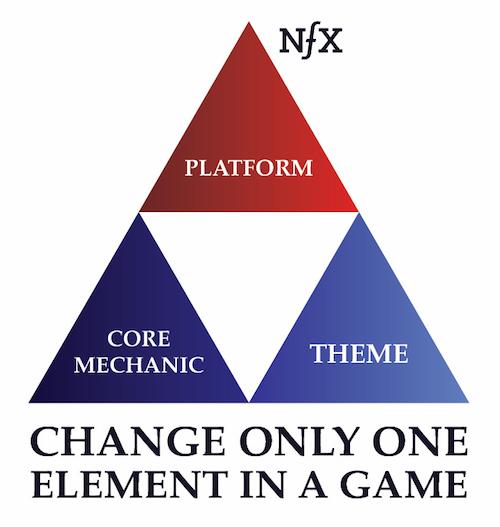

One way to strike that balance is to apply a framework that we learned from the gaming industry: when making a new game, change only one element from what came before. In gaming, there are three big elements:

- Platform – P.C., internet, mobile, Facebook, console, etc.

- Core Mechanic – e.g. build and conquest, slots, collecting, first-person shooter, etc.

- Theme – Dragons, Atlantis, Pirates, Vikings, Space, Vampires, Mafia, etc.

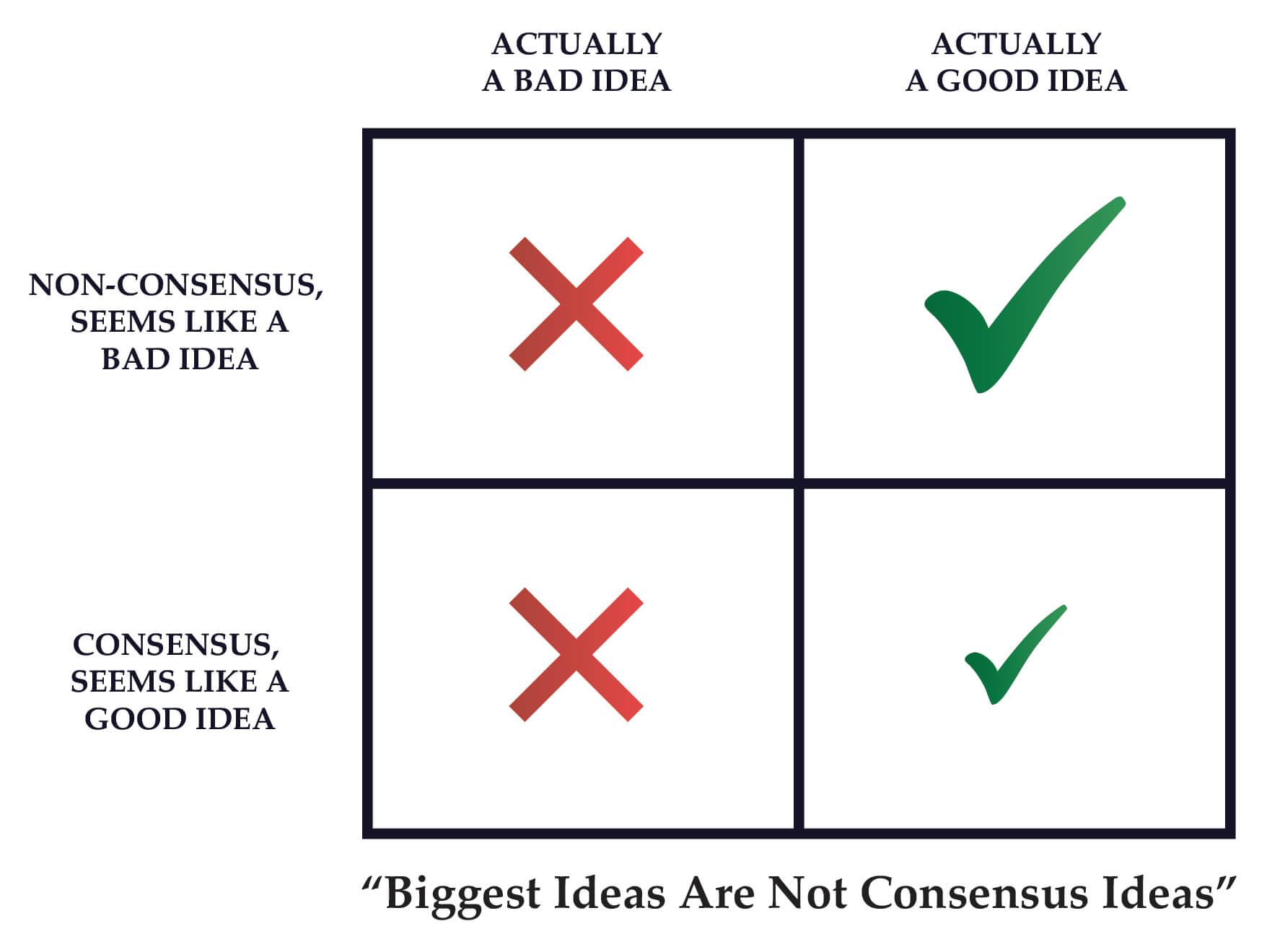

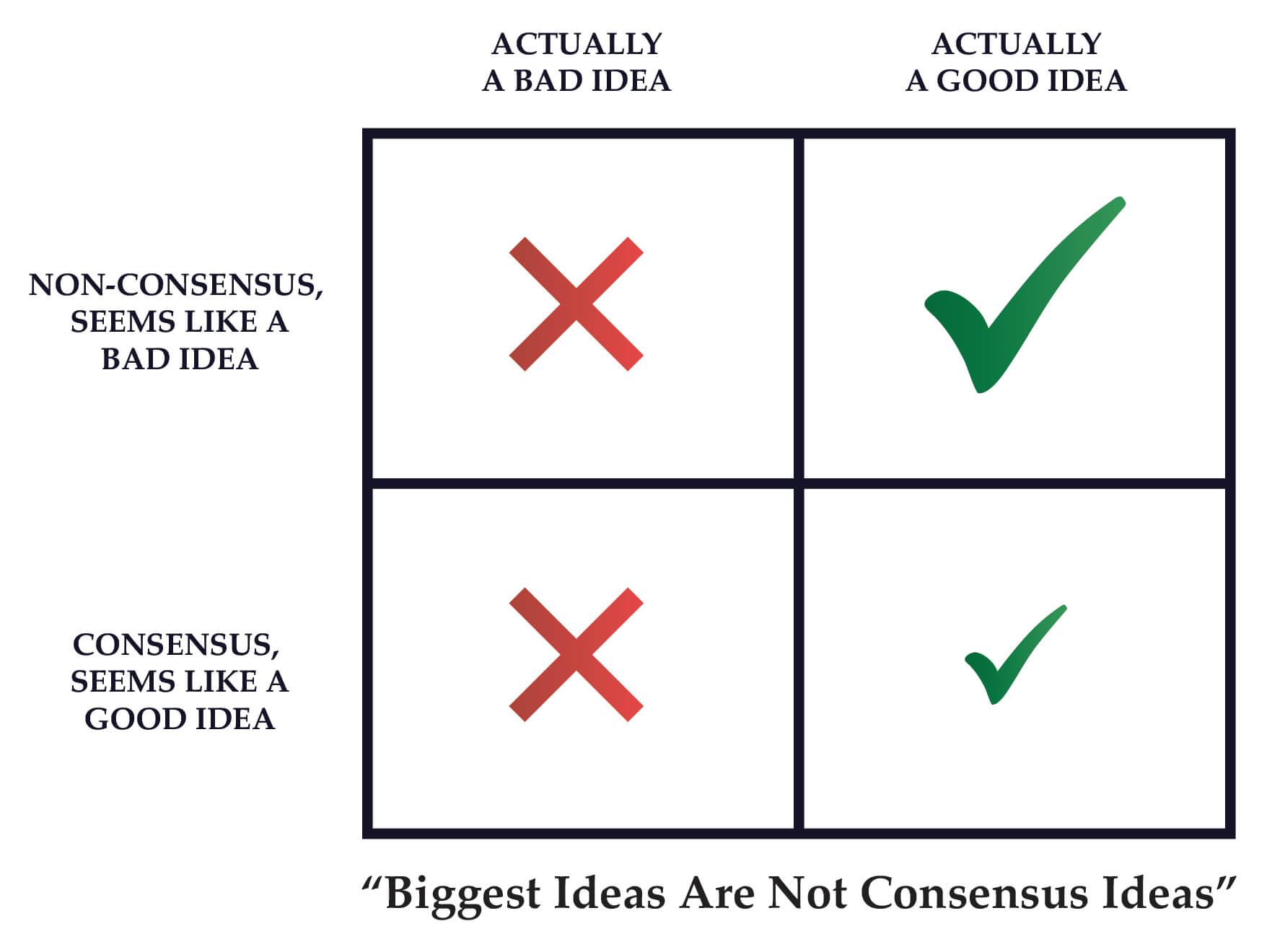

6. Non-Consensus, But Right

“The biggest ideas are not consensus ideas.”

This is a framework that originally came from Howard Marks of Oaktree, which I learned via Andy Rachleff of Wealthfront. Marks realized that many of the biggest ideas both identified some new truth while at the same time being non-consensus ideas, meaning most people didn’t think they looked like good ideas at the beginning.

7. “This would be awesome”

“Many great ideas were first framed as ‘this would be awesome,’ not, ‘this solves a huge problem.’”

Many investors say that *all* pitch decks need to articulate the problem. We don’t agree. Many great companies can’t be — and weren’t — conceived that way.

When evaluating ideas, you should certainly think about how much they are solving a clear problem. But also think about what new opportunities they might be creating.

8. Idea Multiplier

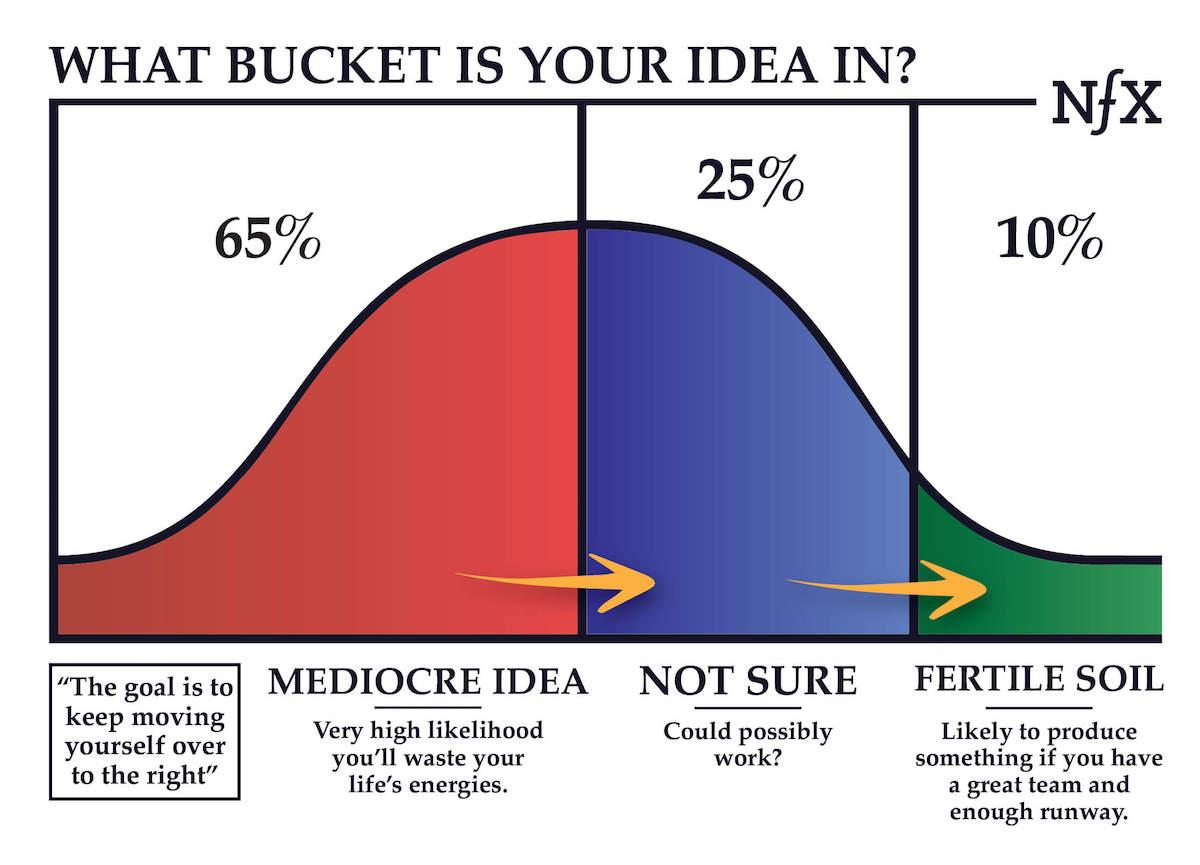

“A great idea is a multiplier for all your efforts down the line, compounding over time.”

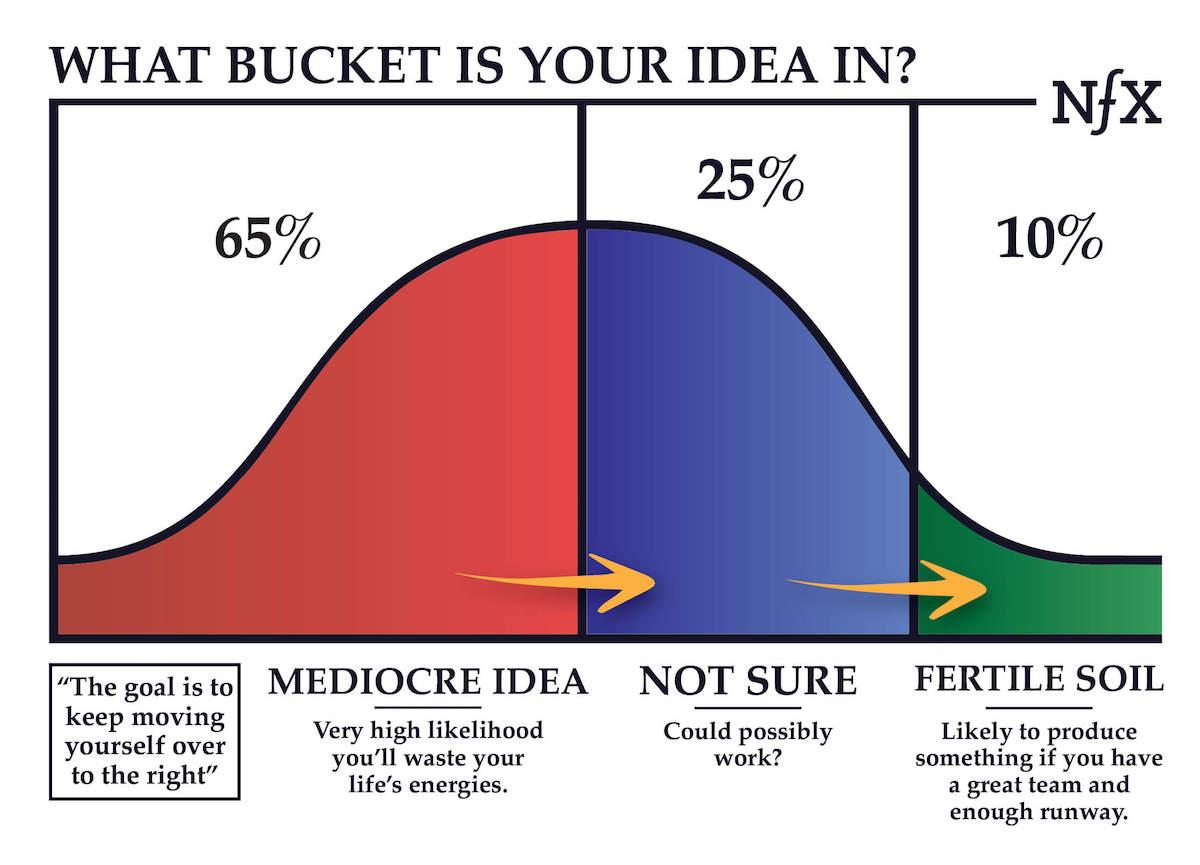

Going in the wrong direction with a startup idea wastes your life’s energies.

In fact, we believe the biggest waste in our startup/VC ecosystem is great people working on mediocre ideas. Note that it’s just as hard to build a mediocre company as a transformative one. Both will take 100% of your time. So you might as well work on a bigger idea.

Product-Market Fit

Whenever we talk with early-stage Founders, they are always worried about growth. It’s an easy mental trap to fall into — up and to the right growth is a windfall for startups because it generally means more users, more revenue, more success.

But product-market fit is the absolute prerequisite to sustainable growth. It’s pointless to try to grow without a great offering that you’ve already proven that people want, need, and love.

Below are 6 useful mental models for navigating to product-market fit.

9. Lean Startup

“The goal of a startup is to figure out the right thing to build — the thing customers want and will pay for — as quickly as possible.” – Eric Ries

Eric Ries’s Lean Startup is a basic theoretical framework for attaining product-market fit. We summarize it as follows:

- Determine who your customers are.

- Find their under-served needs or desires.

- Define your value proposition.

- Specify and build your MVP.

- Test it with customers.

- Iterate fast until you find product-market fit.

10. Product-Promise Fit

“Product-Promise Fit is the theoretical approval that users give to the idea of a product — communicated through language and design — without writing a single line of code.”

No longer is the startup process: “find a problem, build a solution, market it.” The order of operations has been flipped.

Marketing skills (writing, designing, campaigning, and analyzing) now come in a lot earlier.

- Find a problem.

- Describe your solution (in words and design).

- Market your product promise until you find a promise that a big enough group of people really want.

- Then build your MVP.

- Keep measuring, building, and iterating — make sure your users are deriving true value from your product.

- Keep building & marketing your way to sustainable growth.

11. 10 Places to Find PMF

“Product-market fit can be found in more specific places than ‘pain relief’ and ‘gain creator.’”

There are two common places for Founders to look for startup ideas. They are told to either a) find a customer pain point and find a way to relieve that pain, or b) find a potential way to benefit the customer and present them with a “gain creator”.

While that’s not false advice, it’s not complete. It’s too general to be really useful and generate great ideas.

That’s why we’ve developed 10 more specific places where Founders can look for PMF:

- Taking an existing activity and making it 10X easier.

- Make an existing activity 10X better (& networked).

- Create new inventory to be sold in a marketplace.

- Discover new willingness to pay.

- Connect a group of people that were not visibly connected before.

- Give people a new or easier way to make money.

- Turn something digital that isn’t digital.

- Find a way to offer 0 pricing.

- Create a young version of a proven product.

- Find a new ‘pleasure center’ in the mind.

12. “How upset would you be?”

“If you love something, you use it routinely, it makes your life easier or better — and you’d be terribly upset without it — then that product has strong product-market fit.”

One test for product-market fit: look at all the products you are using in your everyday life. Now ask yourself of each product: “If someone took this product away from me, how upset would I be? Would it make my life harder in some way?”

Imagine what would happen if Google Maps and Waze were suddenly deleted from your phone forever — right when you were trying to get somewhere. Similarly, how would you feel if your new iPhone was discontinued?

13. Leaky Bucket

“Top-of-funnel growth means nothing if the users don’t engage or retain.”

There’s little point in aggressively marketing a product that brings no value to its users. They may initially come to check things out but they’ll eventually leave. It’s like pouring water into a leaky bucket: even if it seems full for a second, it is very quickly empty again. That’s why product-market fit, delivering real value to your users, is so critical. It gives you a solid foundation from which to grow.

14. W.O.M.

“Product-market fit tends to generate strong — and measurable — Word-Of-Mouth.”

If you’re solving a real need in someone’s life, it’s only natural that they’ll talk to other people about it.

But many Founders believe their products are driving word-of-mouth when they’re really not. That’s why it’s critical to measure it in relative terms. This can be done with the word-of-mouth coefficient calculation.

Growth

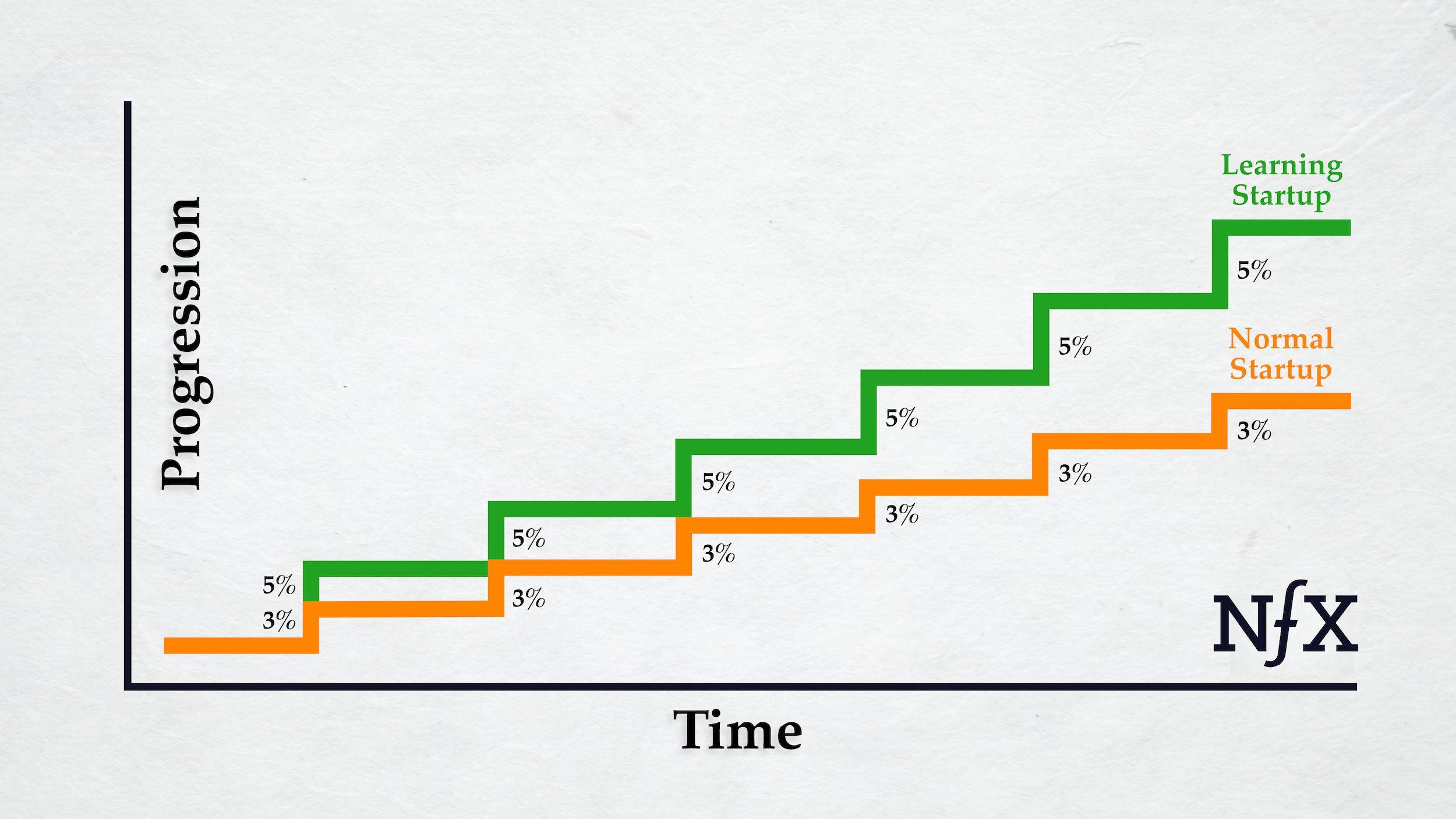

Growth comes from adopting the right psychology — the right mindset. It’s from an approach you bring to your daily work consistently for years.

Here are 11 mental models to get you started.

15. There Are No Silver Bullets

“Growth never comes in the form of an overnight, silver bullet. It comes from adopting the right mindset.”

Growth is a mindset. Tactics change and become outdated, but growth is an endless creative endeavor. You have to develop your psychology for that.

16. Growth Psychology

“Through a thousand small actions every day, Founders can imprint a growth psychology on their startup.”

Growth is ultimately a company-wide effort, but the quality of that effort comes from the psychology of the CEO.

But how can you implement the principles of growth psychology with a team of 6 or more people?

These five steps will go a long way:

- The CEO must teach this mentality to the team, particularly the willingness to sustain repeated small failures.

- Employees must be told that they’re directly responsible for growth as part of their job, even if their title says something else like Product, Engineering, or Marketing. Everyone is on the growth team in this sense, especially the CEO.

- The CEO must give their team clear authority to change the product and allocate human resources in pursuit of breakthrough growth.

- The team should be more aggressive in pushing the boundaries of growth than the CEO. If you’re in a growth position and the CEO is pushing you to run more experiments instead of vice versa, you’re in the wrong job.

- You have to keep taking big swings. 10% growth per month is OK, but once you’re there, there’s probably a way to grow 40% per month. Finding 40% growth, or even 1,000% growth, requires creativity and stepping outside your own box. As our friend Andy Johns pointed out in a conversation with Pete Flint, over-reliance on low-risk A/B testing and optimization will not get you to 1,000% growth.

A well-cultivated growth psychology is the difference between a startup plagued by slow growth and a startup empowered by data visibility, constant movement, and big plays for 1,000% growth.

17. Sustain Pain of Failure

“Success is going from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.”

You’re going to fail daily. Most of the things you put time and effort into will come back negative. Most new tactics aren’t going to work.

You’ve got to be able to mentally move on from the losses. And so do each of the members of your team. It’s the system, it’s the growth psychology that can’t fail.

18. You Need A Powerful Insight

“Behind every interesting tech company, there’s a powerful insight about human psychology.”

In your world, your product is everything. 12 hours per day, 6 days a week. In everyone else’s world, your product is just a tiny sliver (at best — if you’re great).

So the question you have to ask every day is “What is your product to them so that it deserves a place in their complex lives?”

For example:

- Facebook’s insight was the human need for acclaim and social reputation: “See me perform.”

- Snapchat capitalized on the desire for privacy (even secrecy) and ephemerality: “I’m sick of performing”.

- Instagram tapped into the hunger for glamor and appearance. Statuary and portraiture for the internet age: “See my good side.”

- Etsy allows people to buy and sell small-scale craft goods in a time of mass commercialization. “I want to feel unique.”

- WeWork tapped into the desire for community in a rising gig and remote work economy with increasing social atomization: “I want to belong.”

Understand your user psychology — know what you are to them — and your way to 1000% growth will become much clearer.

19. Language First

“The exact language you choose to describe your product and company tells you what you’re doing, and it tells your user what to expect.”

One of the more common mistakes we see is that companies build features first and then “put language on it.”

This is backward. Language should come first.

Your language defines you. It tells users how you are relevant to their life.

“Ridesharing marketplace?” Not relevant to me. “Get a ride in 4 minutes or less?” Ok, now you have my attention. If your button says “share your photos”, the feature is going to be different from “store your photos” and you have to build two different things.

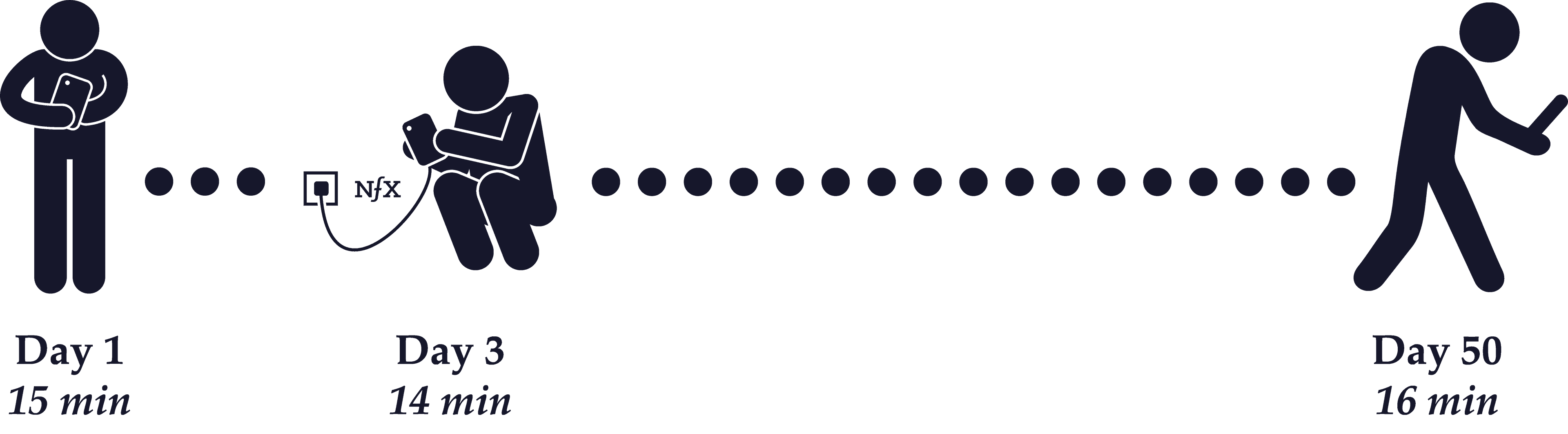

20. Growth Starts with Retention

“If you can retain users, you’ve created something valuable.”

Retention is about how often your users return to use your product. This is the most important growth metric for most startups in the early days because it means you’ve created something valuable.

Understanding retention cohorts is often the best proxy for measuring product-market fit.

21. Always Be Moving

“Move constantly. Make more moves than anyone else. To grow, you have to run quicker experiments. Iterate faster. Never stop.”

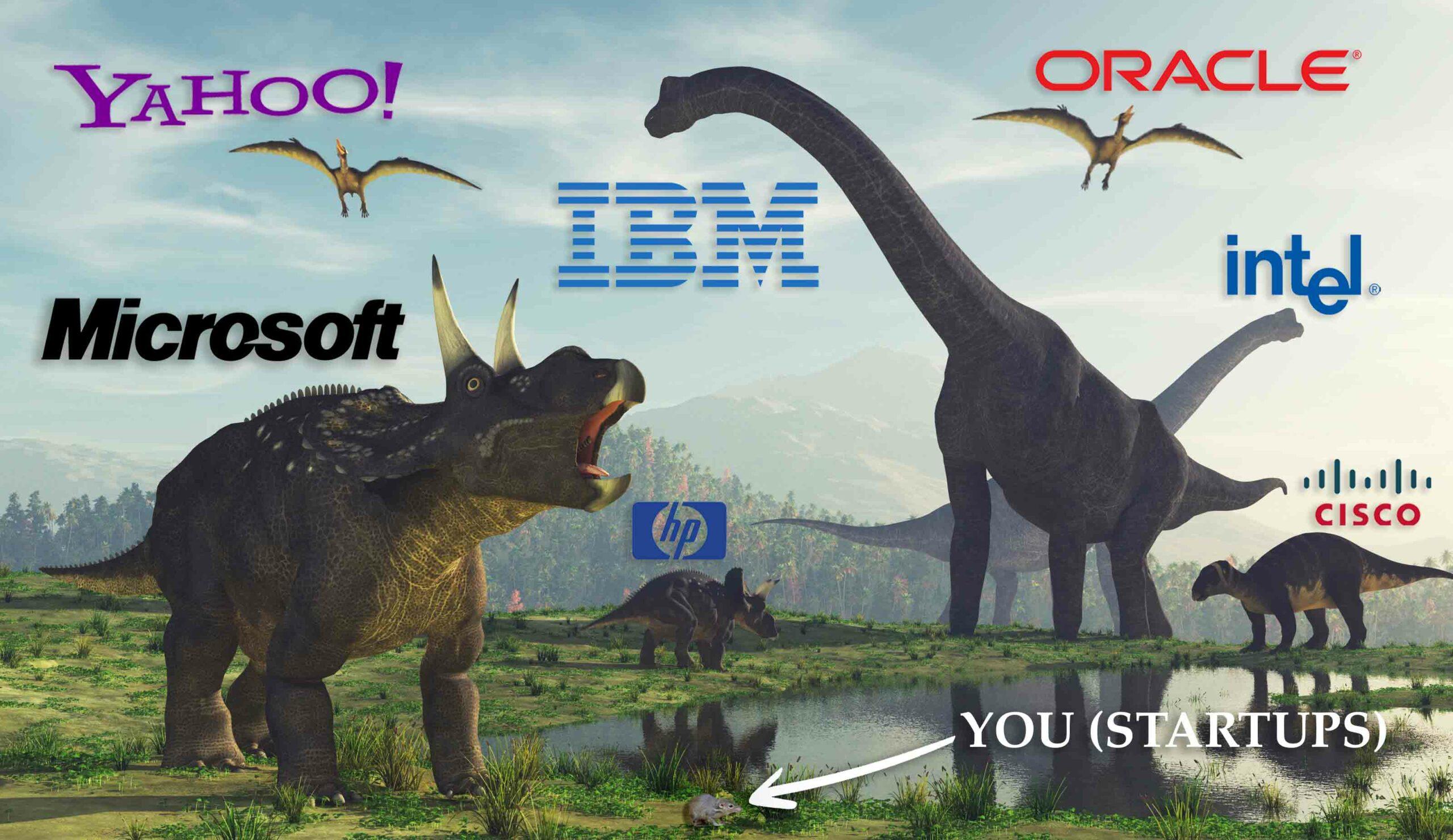

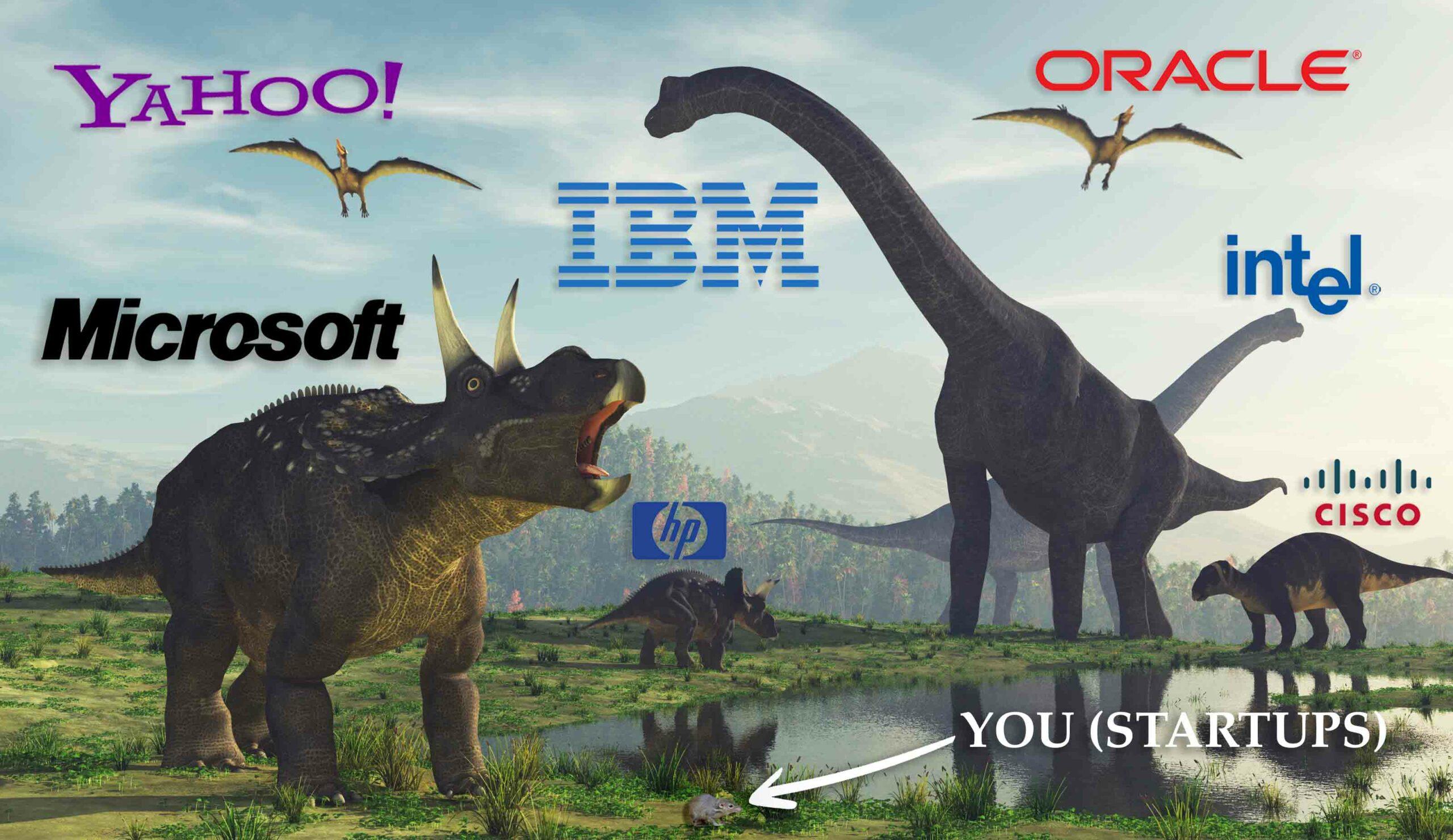

Go back 85 million years ago. Who was the dominant life form on the planet?

Dinosaurs. They were huge. They were on top of the food chain. They were the giants that ruled the earth.

But they weren’t alone. Scurrying in the underbrush you had a tiny, shrew-like creature — the ancestor of modern mammals. The shrew had no advantages against the dinosaurs except one… it moved constantly. Every minute of the day, even in its sleep, it kept moving.

Then an asteroid came, and everything changed. Survival suddenly took on new dimensions. Ultimately, the shrew won out. Why? Because its small size and speed prove to be advantageous in times of rapid change, while the dinosaurs, victims of their own dominance, lumbered to extinction. Their huge size became their greatest weakness.

Startups today should be familiar with the shrew’s story and adopt its mindset. You, too, inhabit a world dominated by giants. You, too, have no advantages, except one: speed.

22. Data Love

“You must test, measure, and iterate — a process backed by data. That’s the engine that powers growth.”

“Data-driven” can’t be a buzzword. You have to truly commit to it. Devote significant engineering resources to measurement — even up to half of your engineering resources.

You have to love your data. That has to be your psychology.

When we go and look at startups, we want to see everybody looking at triangle retention charts. We want to see the stats dashboard displayed on a big screen on the wall of your office in full view of everyone. Seeing that means that the Founder took the time and effort out of her weekend to go out and get a TV, hall it up, deal with the wiring and the mounting and all the other headaches of getting it set up. It’s a sign that the Founder really loves their data.

23. Wundt Curve

“We are attracted by things that are new enough to not be stale, but not too new to be strange.”

The attraction of novelty was identified early on by Wilhelm Wundt, one of the founders of modern psychology who came up with the Wundt Curve — a bell-curve distribution between novelty at one end and familiarity at the other.

We are always looking for the next new thing. We are motivated to share new products and new information because it makes us look like we’re ahead of the (Wundt) curve.

People share things that are entertaining because the risks are low and it allows people to interact and bond in ways that feel safe and warm.

24. Viral Thinking

“Make your product broken unless people share.”

If users can’t get the utility that they want from the product, they will look for ways to share. And when any of us consider sharing something online or offline, we unconsciously make a trade-off between benefit and costs:

- How might sharing this benefit me (the sharer) or you (the audience/recipient) either via utility or via status/reputation?

- How much time and effort (friction) will I have to spend to share this?

The differential between 1 and 2 will give you higher conversion to sharing, and A/B testing can help you with that differential. Growth tactics often focus on this.

Understanding psychological motivations expand your toolkit to maximize the differential and really speak to your users.

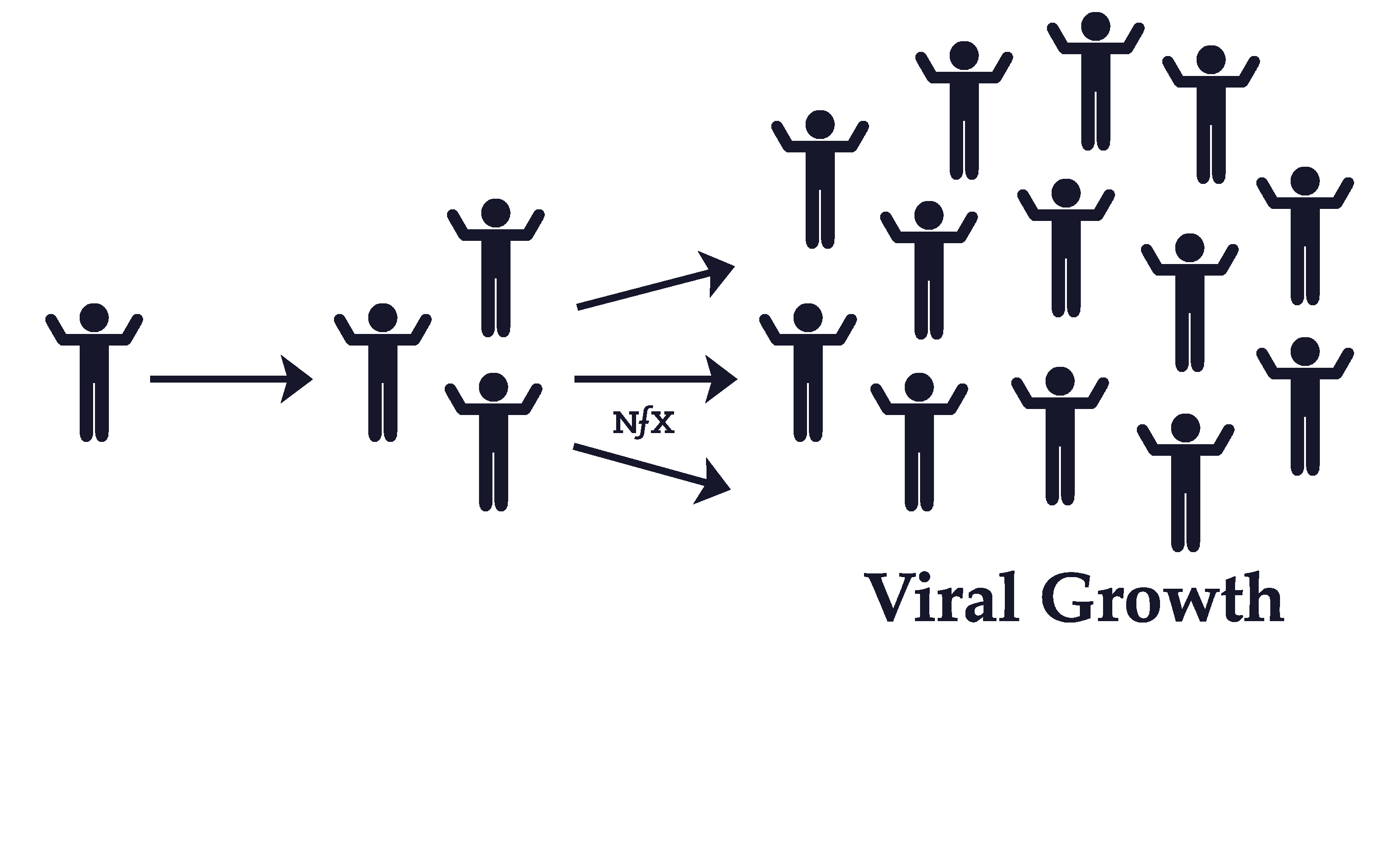

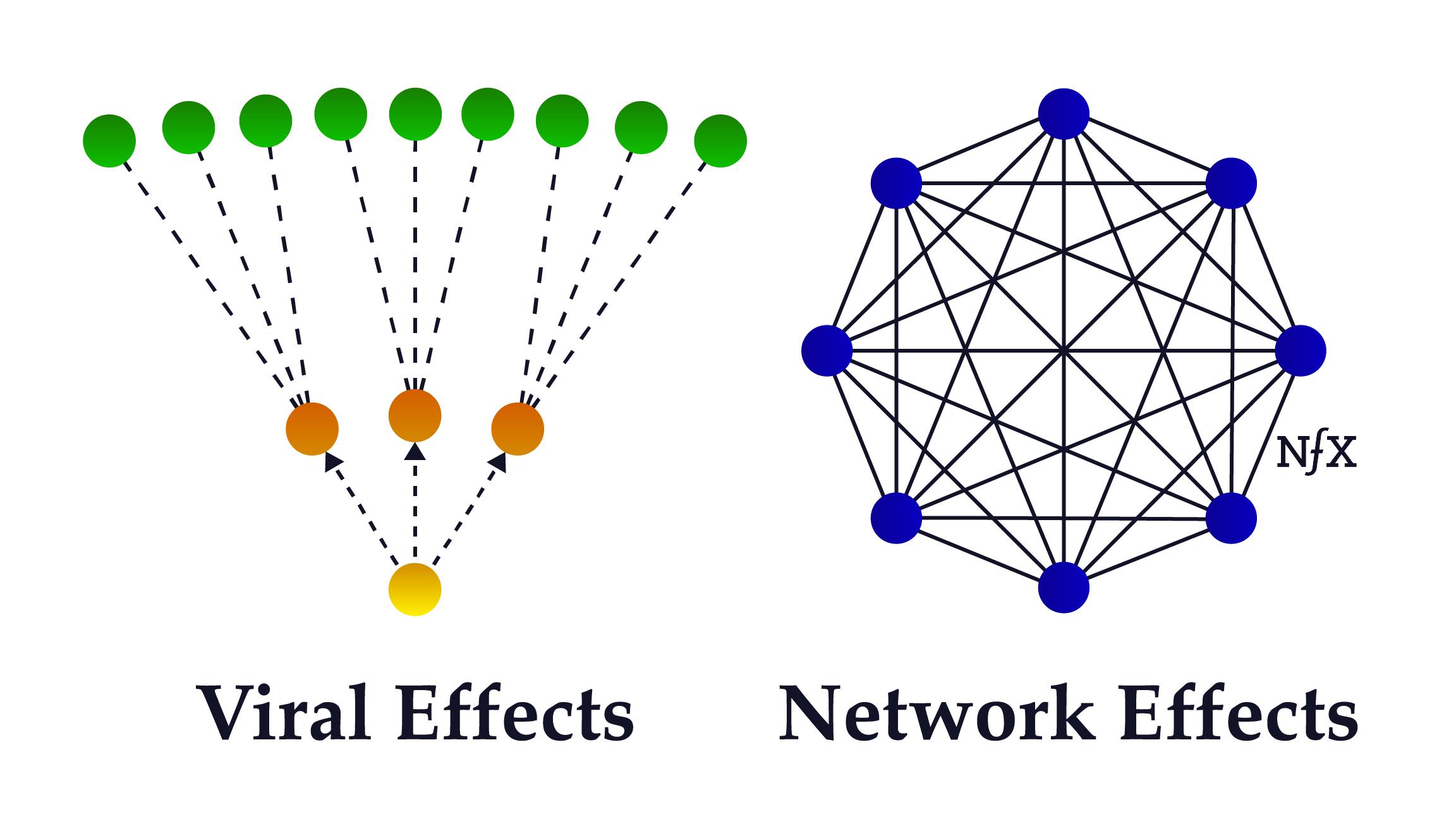

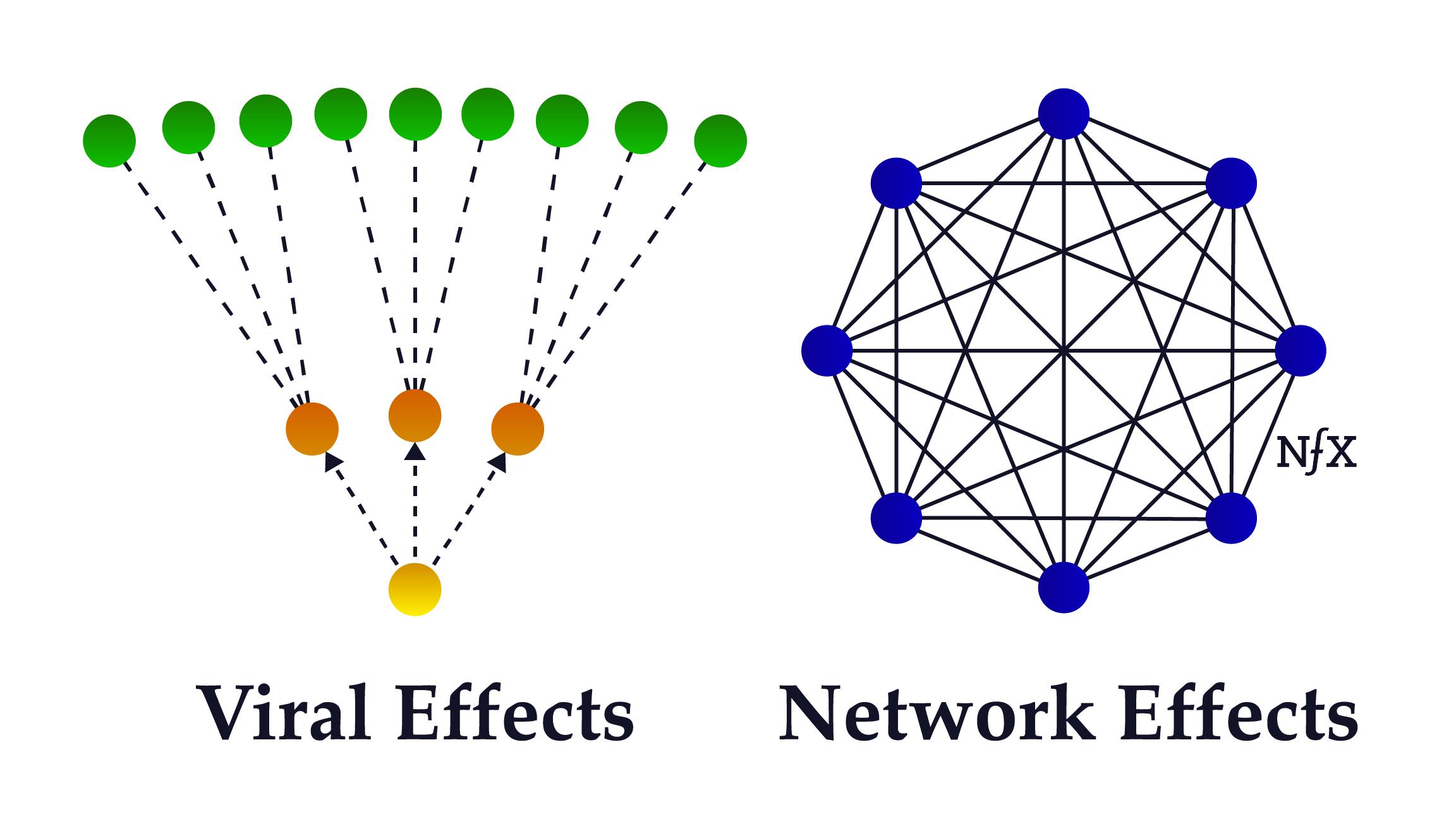

25. Viral Effects Are Not Network Effects

“Network effects are about adding value and defensibility to your product, and viral effects are about getting new users for free.”

Viral effects are about the growth of new users. Viral effects are when you get your existing customers to get you more new customers, ideally for free.

Network effects are about adding value and defensibility to your product. A network effect is when every customer of your product adds incremental value to all the other customers of your product so that it becomes difficult for customers to find any alternative product which gives them as much value.

While viral effects are a useful attribute of products to reduce the expense of acquiring new users, network effects remain the key driver of value creation for startups in the digital age by keeping people using them.

Fundraising

Fundraising is one of the most challenging parts of being a Founder because it most often works opposite your instincts. It is just as much about what not to do as it is about what to do.

We’ve found these 5 mental models bring Founders incredible learning, leverage, and ultimately, the best Founder-Investor partnerships (and success) over time.

26. Know What You’re Likely To Get Wrong

“Fundraising is a learned skill – and VCs almost always have the upper-hand because they deal with it all day, everyday.”

Fundraising is not a natural talent for most, and it’s easy to make mistakes in judgment along the way. Here is a list of the most common mistakes we see Founders make time and again in their understanding of fundraising:

- Misjudging the level of a prospective investor’s interest.

- Underestimating how long the fundraising process will actually take.

- Not understanding or accurately predicting the terms that you’ll be offered.

- Hearing a “yes” when the investor actually said “maybe”.

- In general, misperceiving what the investor really thinks of you.

Chances are, one or all of these things will happen. Why? Because investors play this game all day, and you only do it occasionally.

So don’t trust your instincts too much. The more awareness you have about the limitations of your startup fundraising experience compared to those of VCs, the more empowered you will be throughout the fundraising process and beyond.

27. Divide & Conquer

“Aim to reduce the fundraising workload of everyone other than the person leading the process.”

Before starting out, it’s important to assign clear fundraising roles within the team. CEOs should be in charge of fundraising. This may be uncomfortable given how collaborative startups are, but investors expect the CEO to lead the charge. Delegating fundraising to another Founder is likely to raise many questions that will likely outweigh the potential benefit.

The rest of the team should focus on the actual business as much as possible — the progress of the business is going to be critical to your fundraising success. In most cases, the most balanced approach is to go CEO-only for the first meeting and include the full founding team for subsequent meetings.

28. Fundraising Is Not A Distraction

“As the CEO, understand and accept that fundraising is not a distraction — it is your biggest mission-critical task.”

Founders often complain that fundraising is a distraction from the day-to-day of running their company — but thinking of it as a distraction means you haven’t laser-focused on fundraising as your priority.

29. Fundraising Is Selling

“Your company is a product and VCs are your customers.”

Many Founders miss the fact that your company is itself a product, and for the customer (investor) to buy (invest in) it, you need to be as prepared as possible. As a Founder you wouldn’t go to market with a sloppy website or bad first-time user experience — why do that with fundraising?

To start, make sure you have the best fundraising material: including a polished and rehearsed pitch deck, one-pager, and a financial model. Even the wording of the emails you send should be tested and optimized.

30. Don’t Just Pitch VCs, Learn From Them

“When you meet with VCs, don’t just fixate on getting their money — learn from them.”

For any given meeting with a VC, the chance it will result in funding is between 1% and 10%. That means you have 90%+ probability that you will not raise money from this person. So if that is your only goal for that meeting, you are wasting 90%+ of your meetings.

It’s better to view the meeting as an opportunity for you to build your company using the information you get from the VC, not just the money you might get. This will give you a higher return on your time.

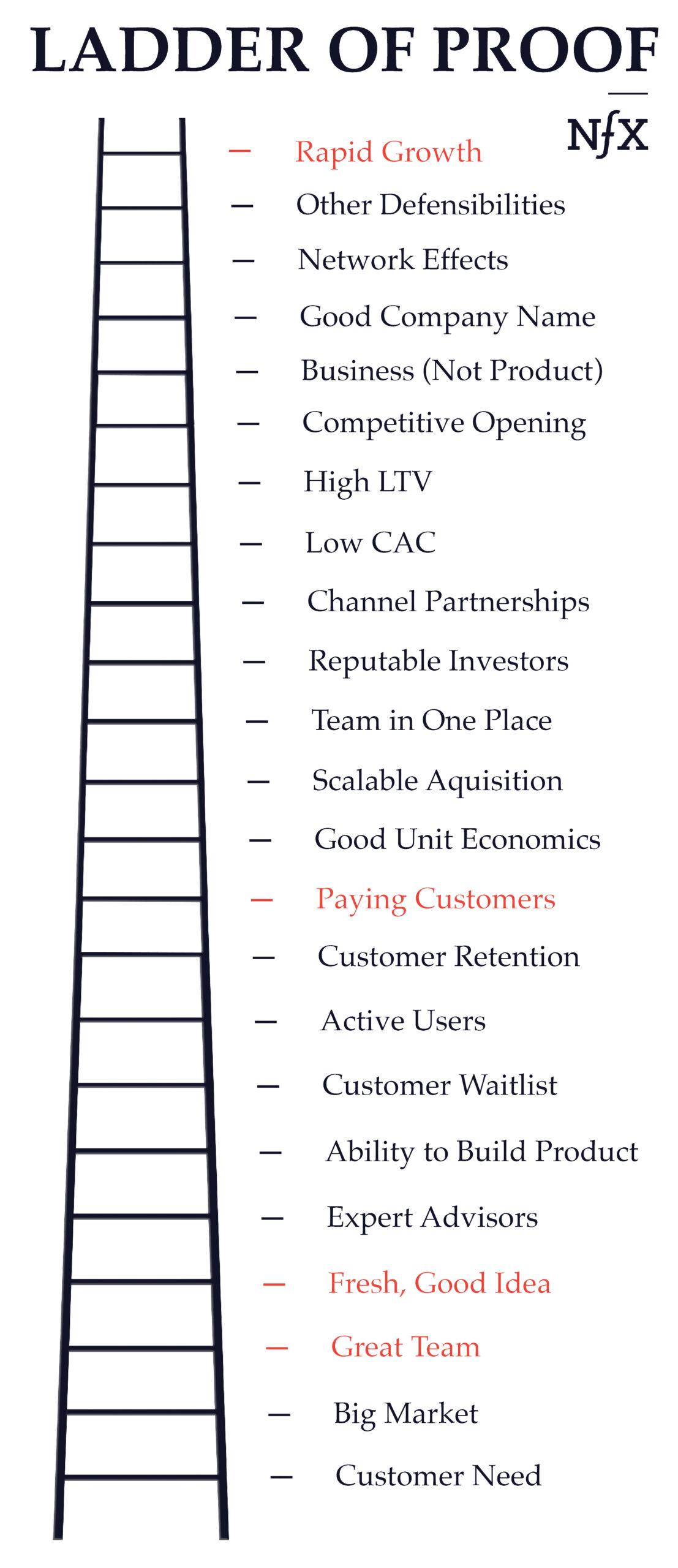

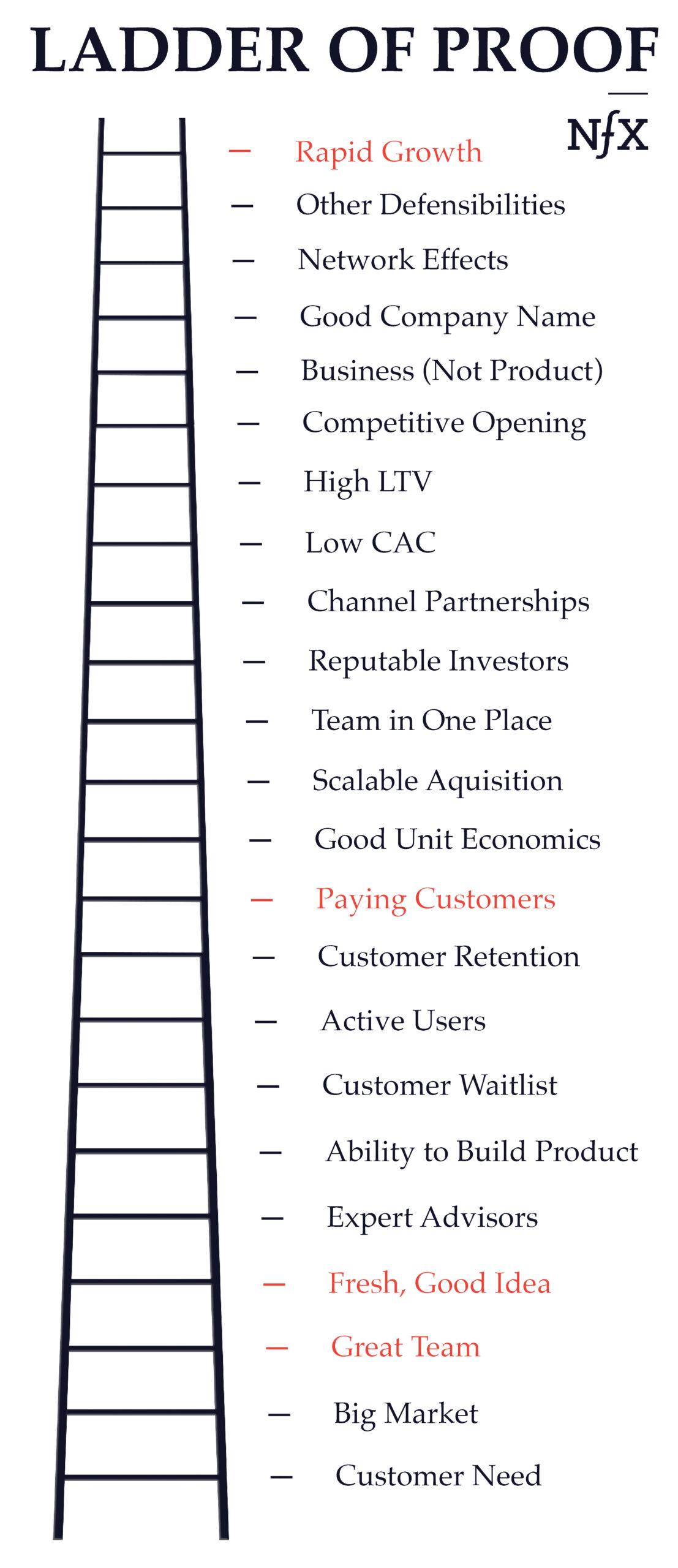

31. “Ladder of Proof”

“The further up the ‘Ladder of Proof’ a startup climbs, the more signals it’s sending to investors that it’s an attractive investment.”

Investors have a mental framework that lets them judge a startup based on a core group of predictors for risk and success that we call the “Ladder of Proof.”

The key is to be aware of your place on the Ladder so you can communicate successfully with each VC you speak with, with each employee you’re recruiting, and each journalist you’re pitching.

Here’s how a “Ladder of Proof” works:

- Each rung represents a predictor of risk or success.

- Some rungs — like rapid growth, a great team, or paying customers — are more powerful than others. And hitting on those rungs (marked in red) can level a startup up to a place where I’m willing to overlook some of the lower rungs (for now).

- Different VCs will emphasize different rungs. The key is to understand your audience — which VC you’re talking to — in order to determine whether you fit their preferences.

Defensibility

In the old days, the business literature listed many ways to create defensibility: unique access to raw materials, favorable geographic location, government regulations like tariffs, patents, licenses, and more.

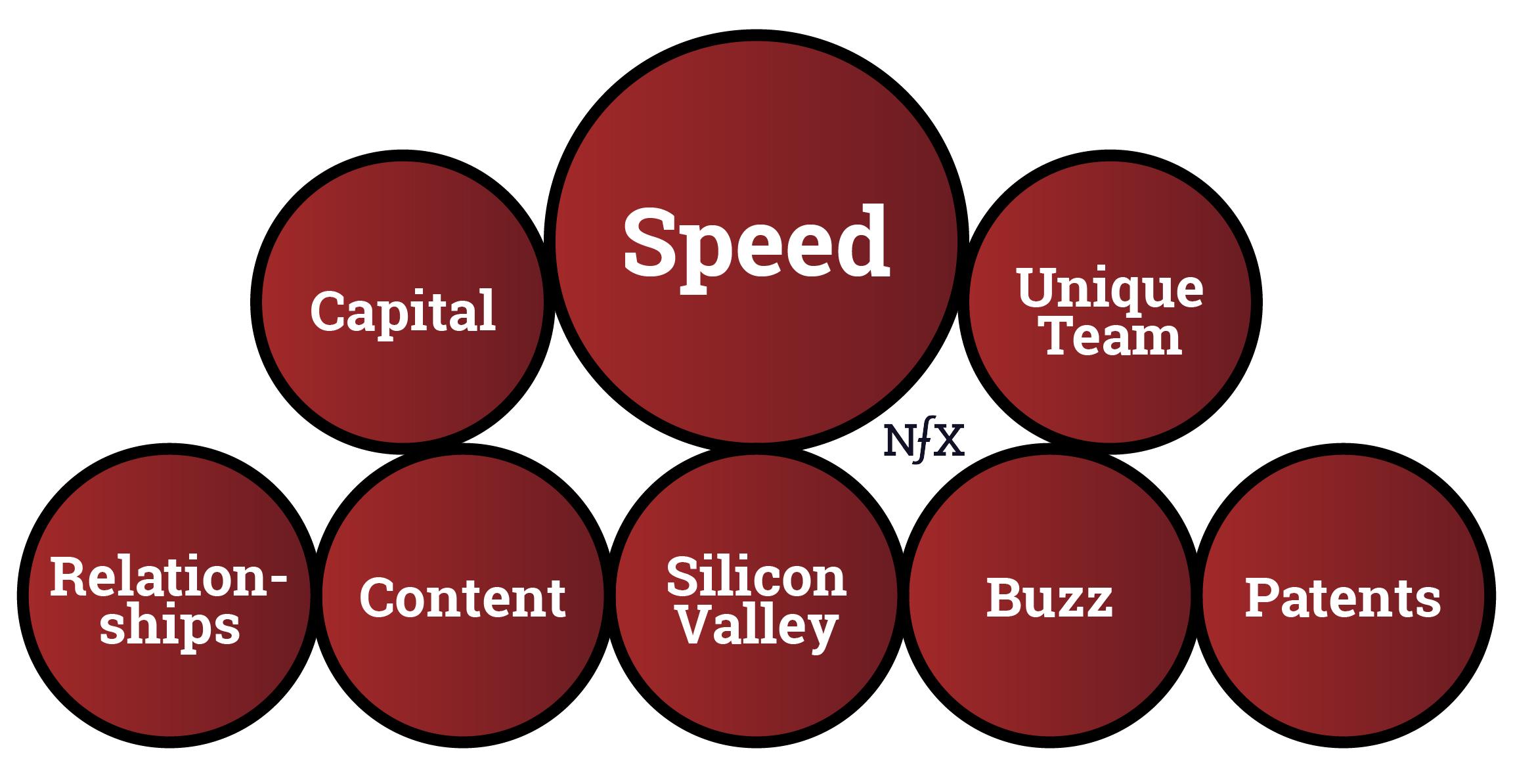

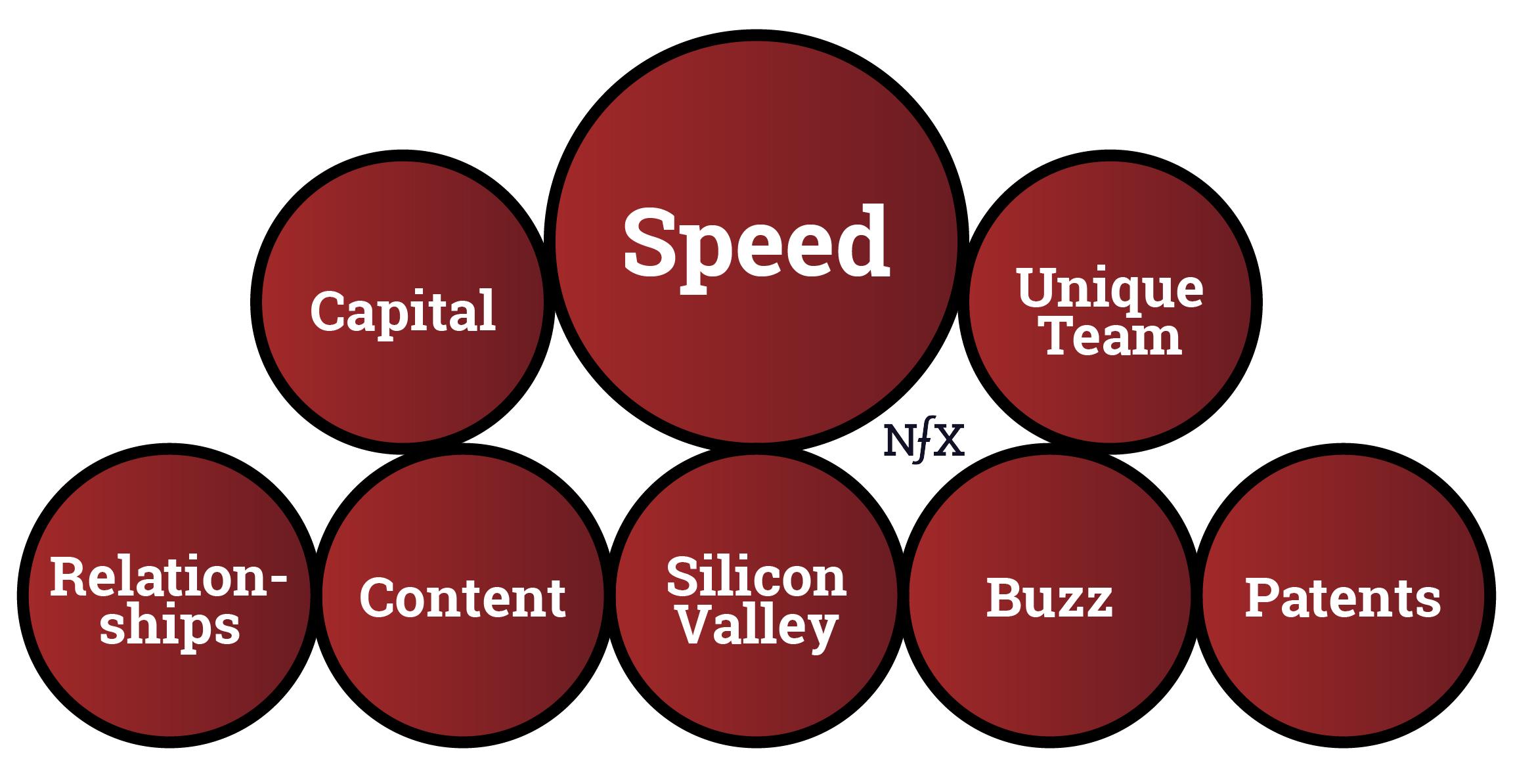

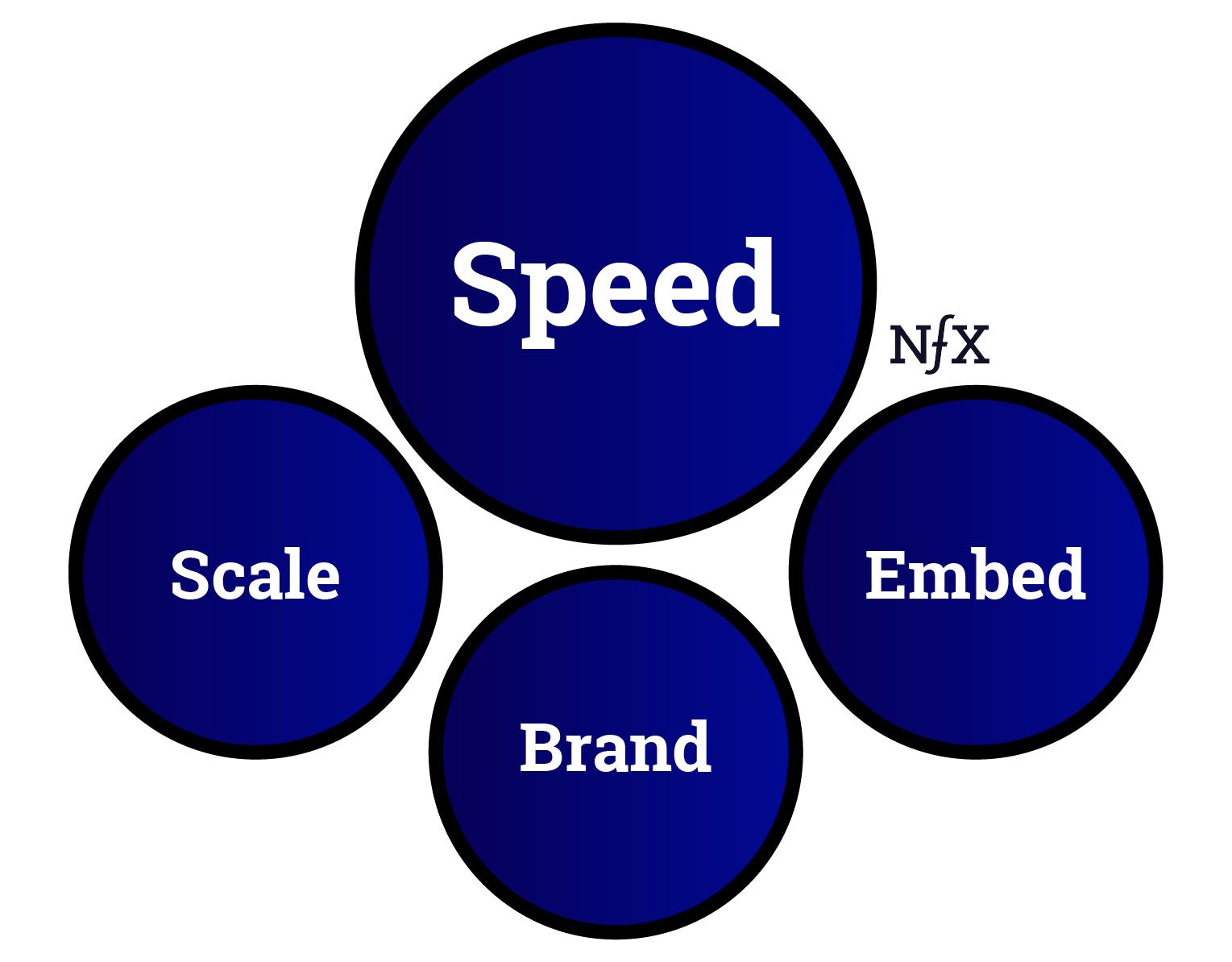

But what we’re left with in the digital age is a shortlist of competitive advantages, just a handful of true defensibilities, and 6 mental models for navigating them both.

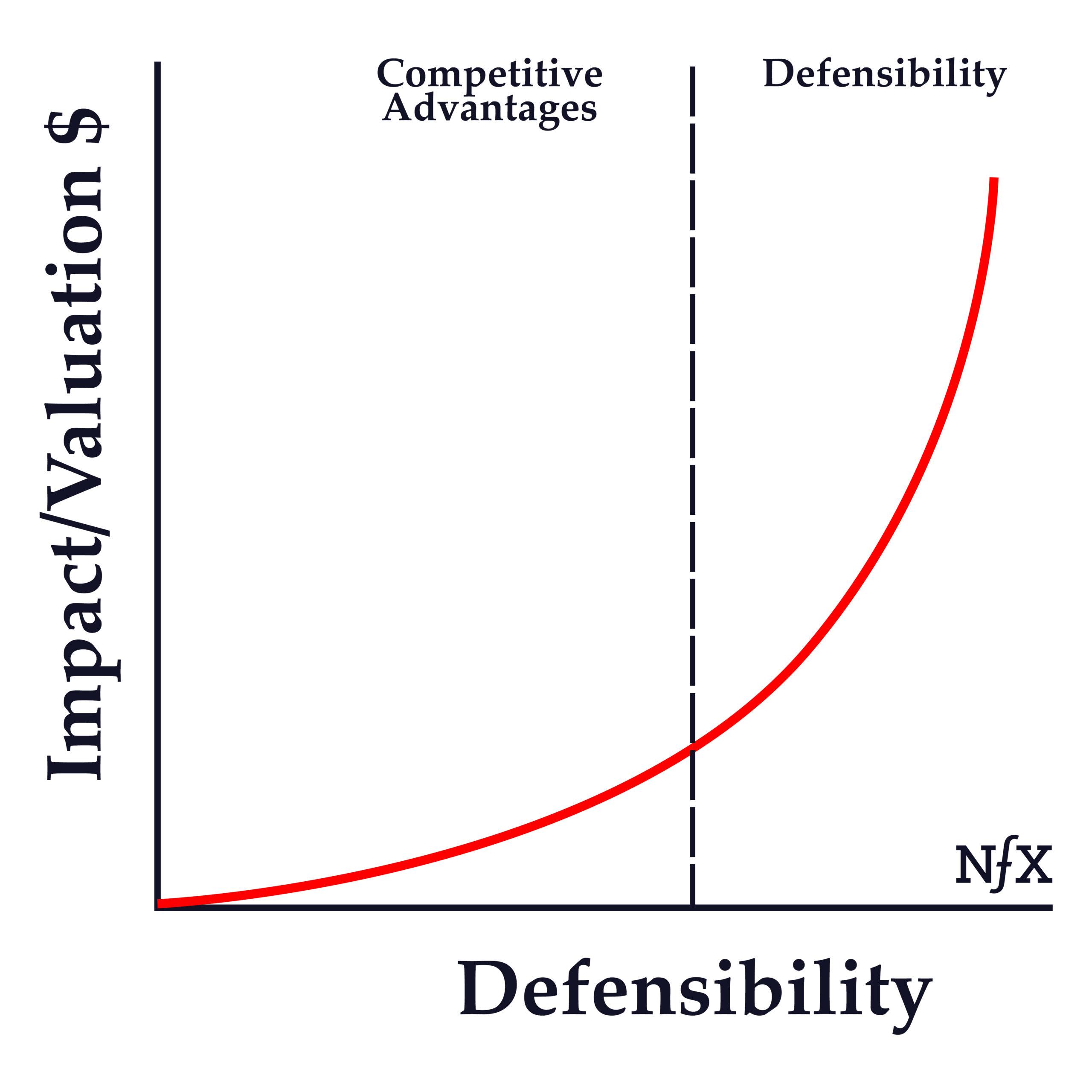

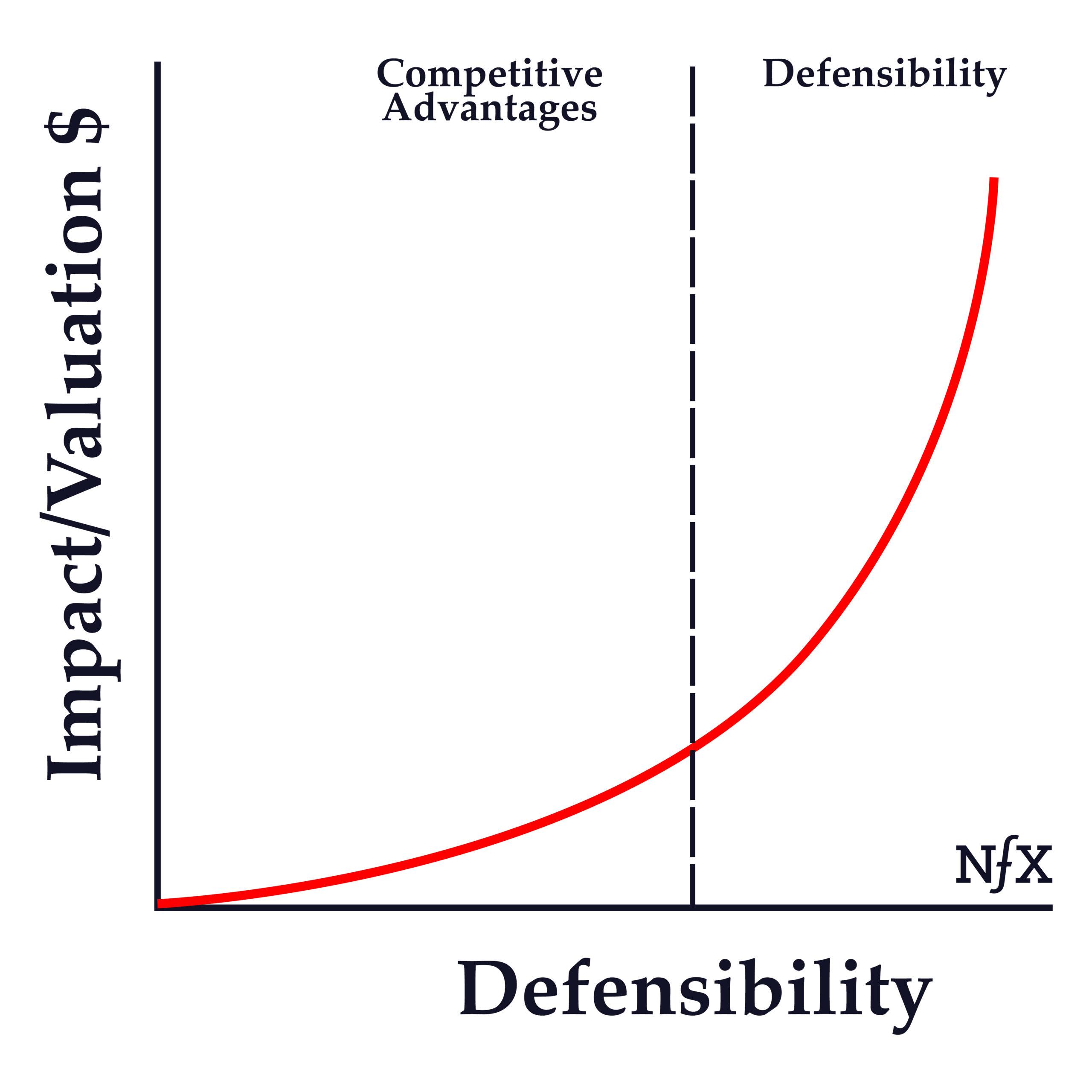

32. Defensibility Adds The Most Value

“Competitive advantages help your company become successful. Defensibility helps you stay there.”

If you build a business with good competitive advantages, your value grows linearly as you grow revenues. That’s good. But if you’re able to move past competitive advantages to true defensibility — to really being able to protect your business from competition — your value grows exponentially.

Here are eight competitive advantages that are currently working well in the digital world:

In the digital world, there are few defensibilities. Today, we count just four.

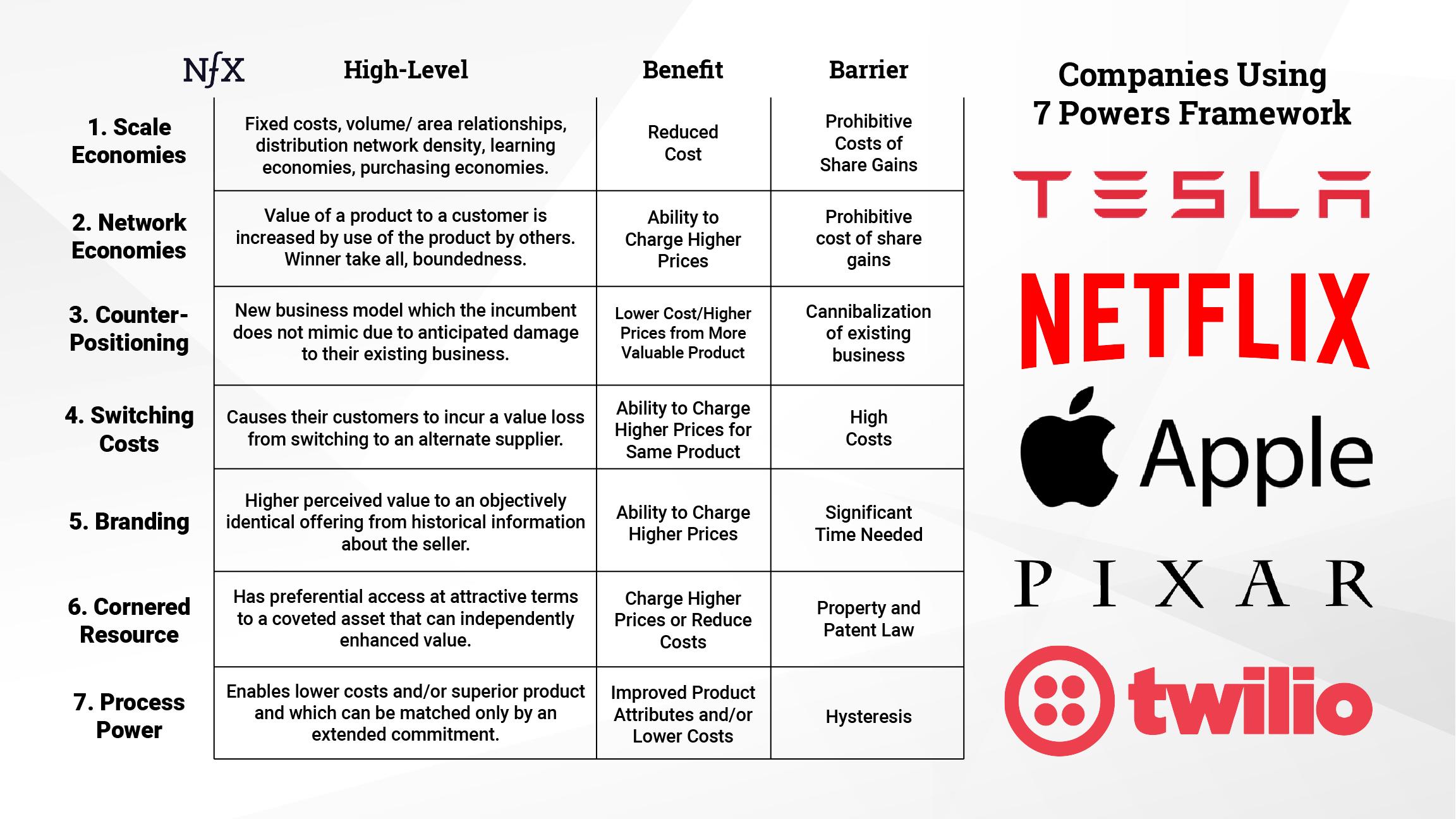

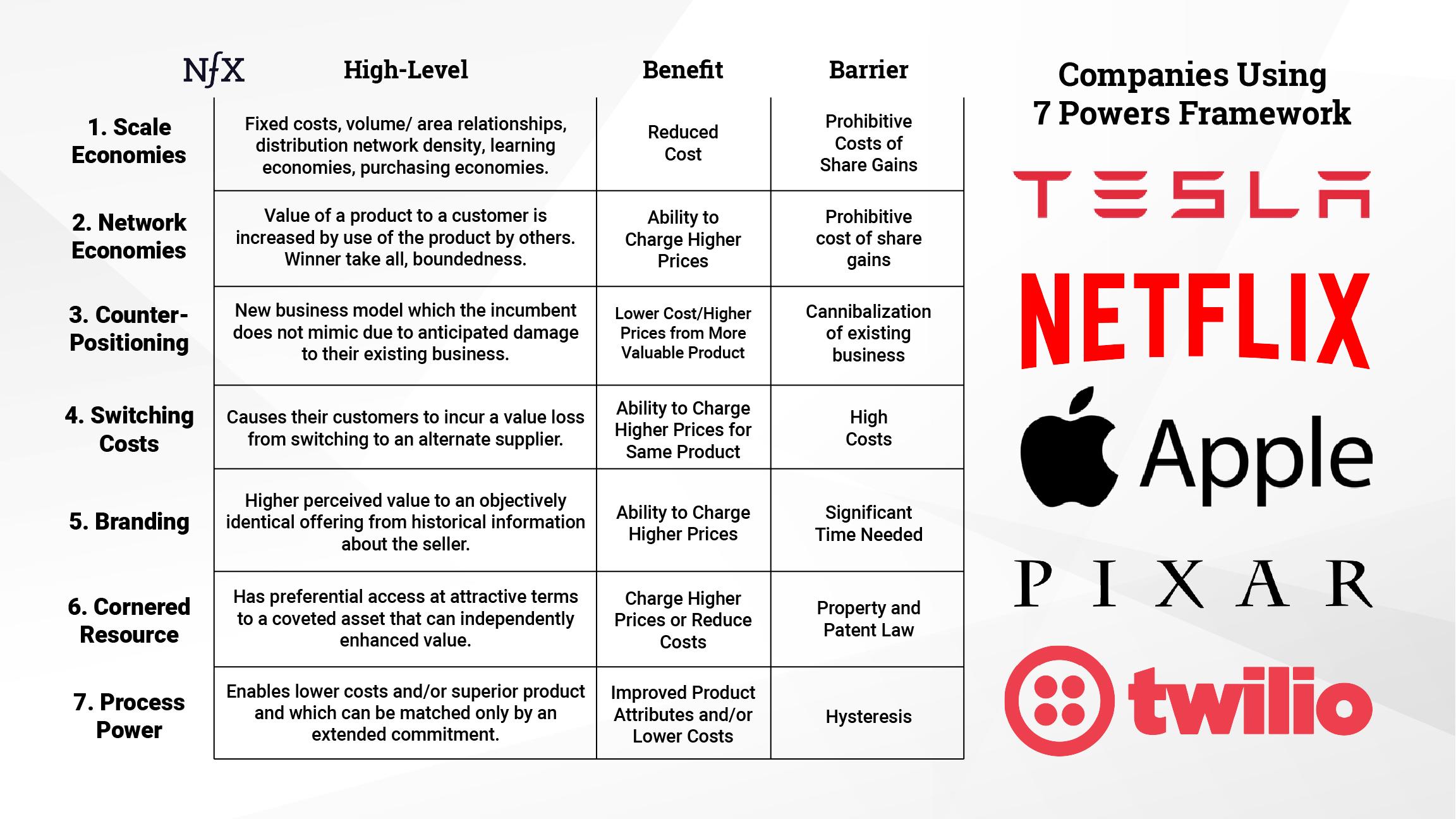

33. “7 Powers”

“Performance is a trailing indicator. Power is a leading one.”

“Power” in this context is the underlying set of mechanisms that makes your company defensible: scale economies, network economies, counter positioning, switching costs, branding, cornered resource, and process power.

“7 Powers” is a framework developed by author, strategist, and Stanford Professor, Hamilton Helmer, a recent guest of the NFX podcast.

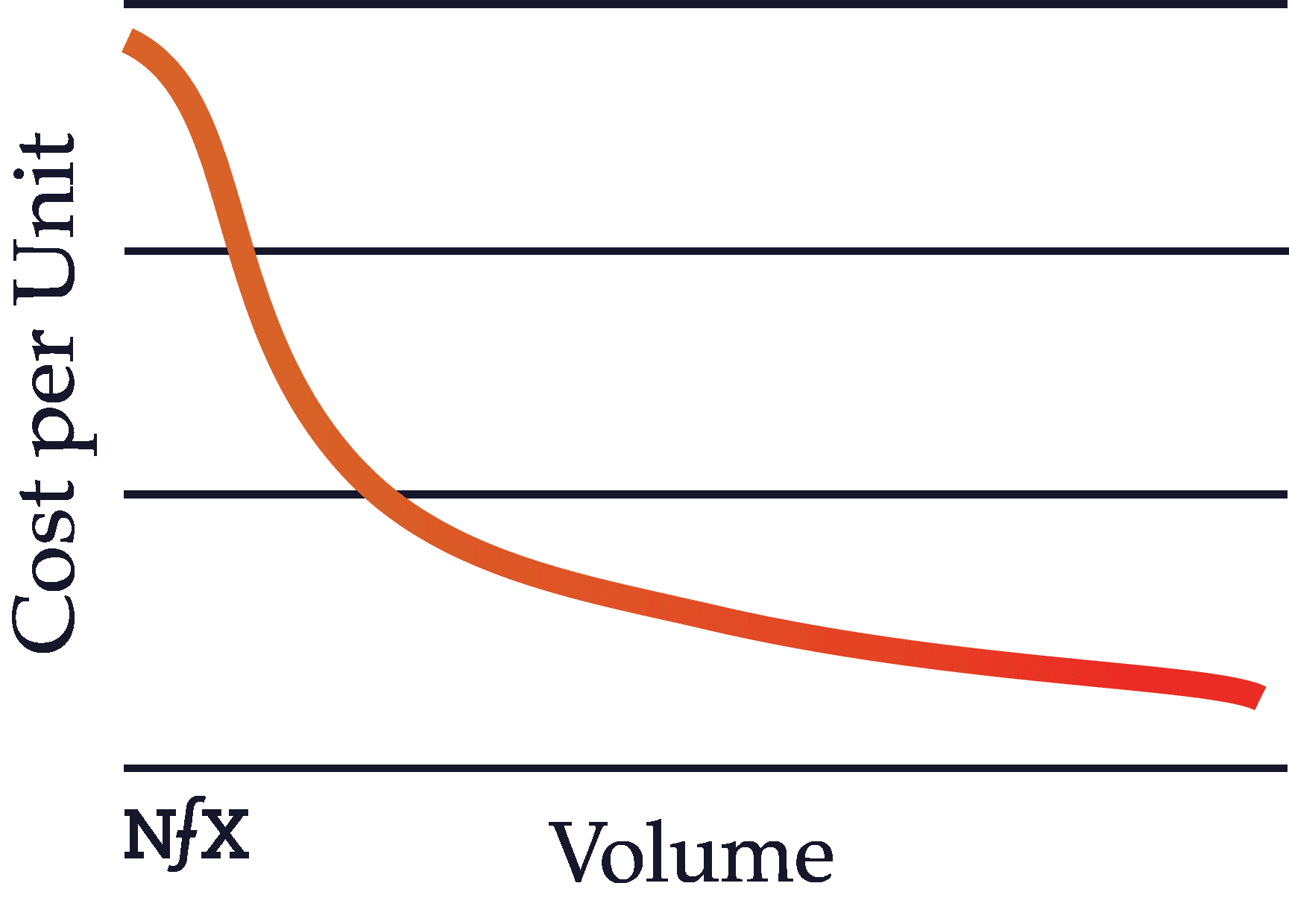

34. Scale Effects

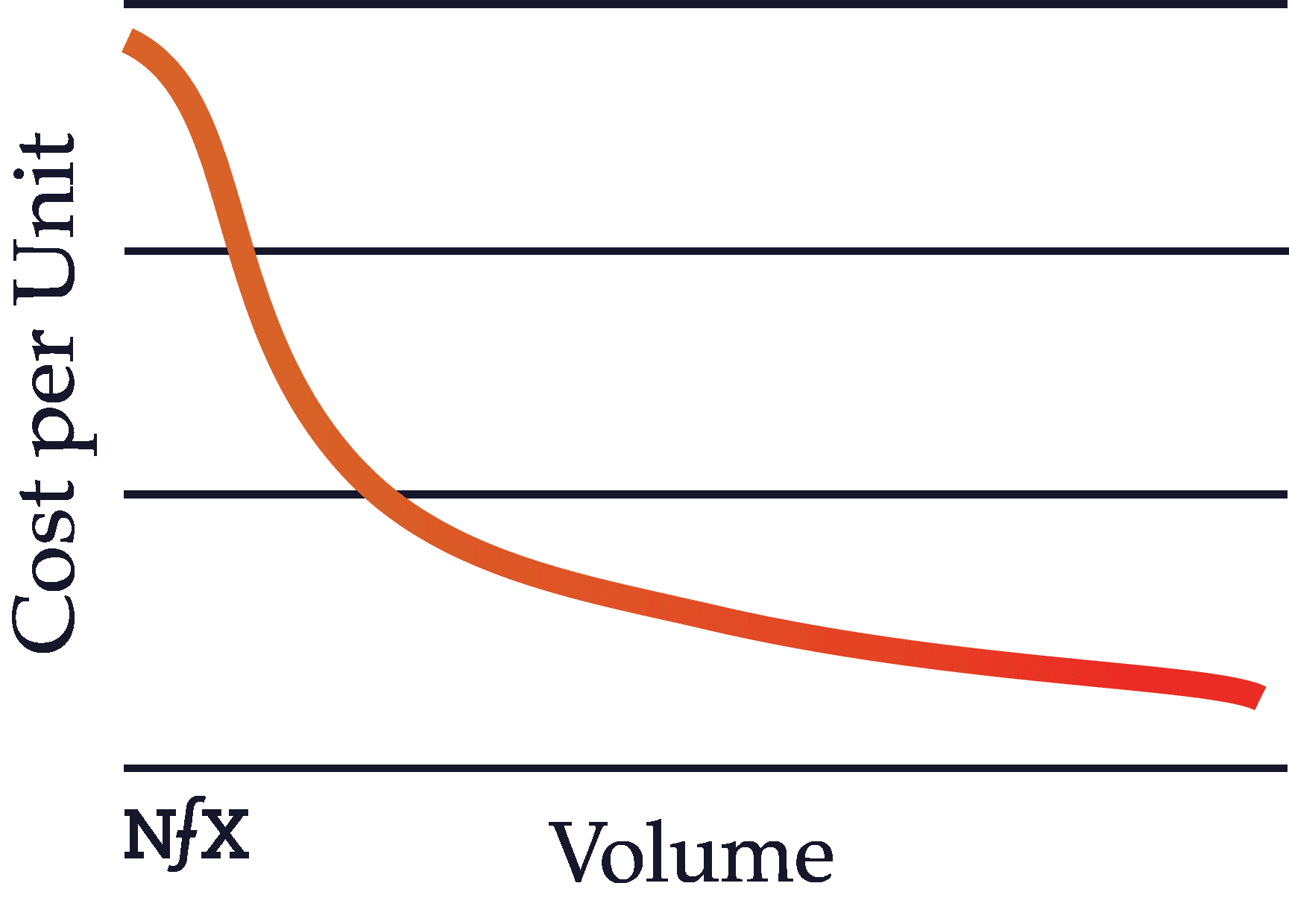

“Scale effects means per unit production costs get cheaper with more volume.”

The best way to understand scale is that as well-run companies get bigger, their per unit production costs get cheaper. As a scale effect starts to kick in, the company with a scale advantage becomes the obvious mathematical choice for customers.

In other words, more users drive greater volume, which drives cheaper prices from suppliers, which drives lower prices for customers, which drives higher conversion rates for ads, which makes advertising more effective than the competition, and so on and so forth.

With scale, the numbers all begin to move in your favor and math is hard to compete with. This concept is known in the academic literature as “economies of scale.” In short, per unit production costs get cheaper.

35. Brand Power

“A well-established brand identity comes with psychological switching costs.”

Brand power arises not only when people know who you are and what you do, but when they are less likely to switch to an unknown or lesser-known brand from yours because psychologically they will default toward what’s familiar.

People tend to be risk-averse and avoid the unknown. When you have brand recognition, people are familiar with what you are and what you do. That gives you an edge.

Brand defensibility is so critical in today’s attention economy that, paradoxically, even negative brand awareness can help make your business more defensible (within certain limits).

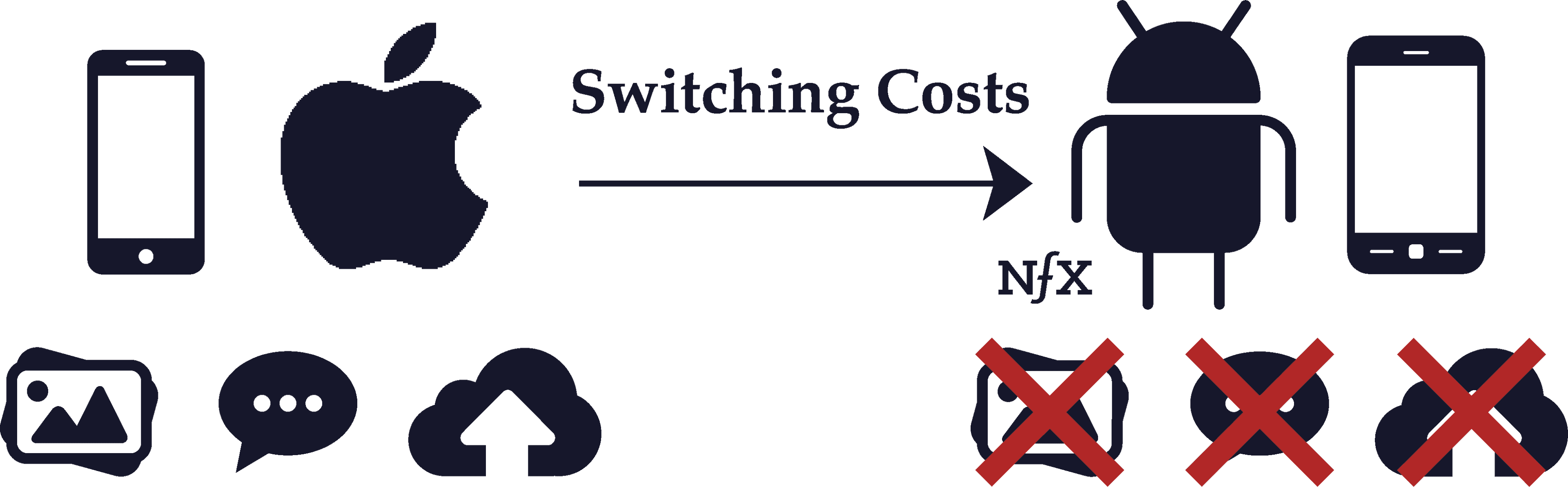

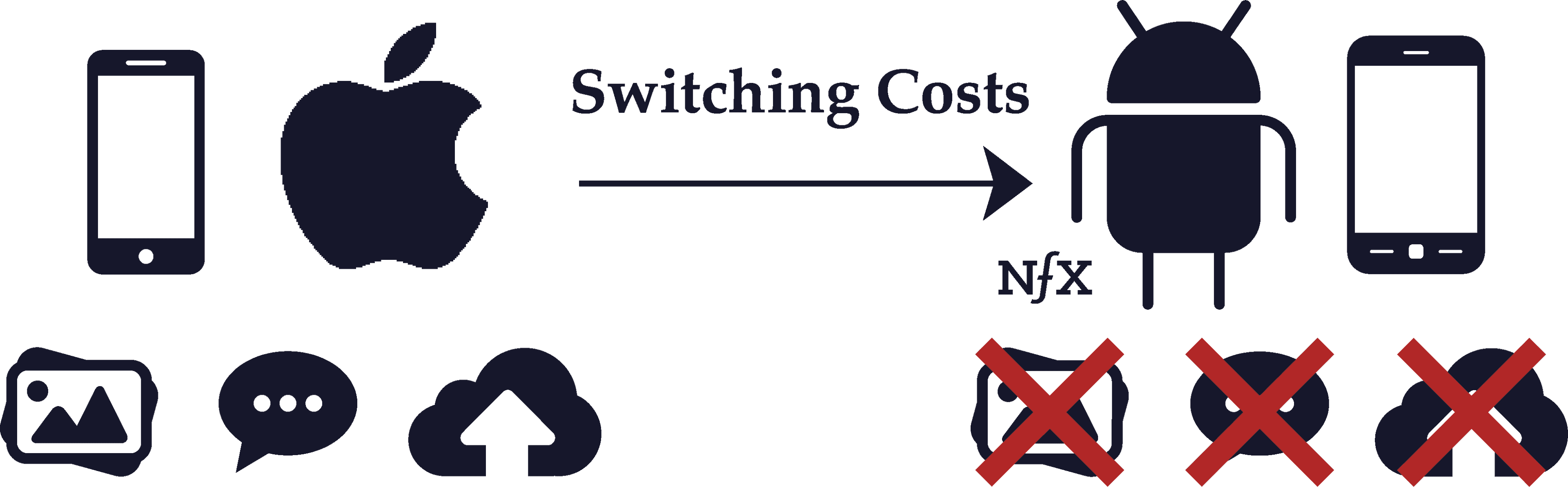

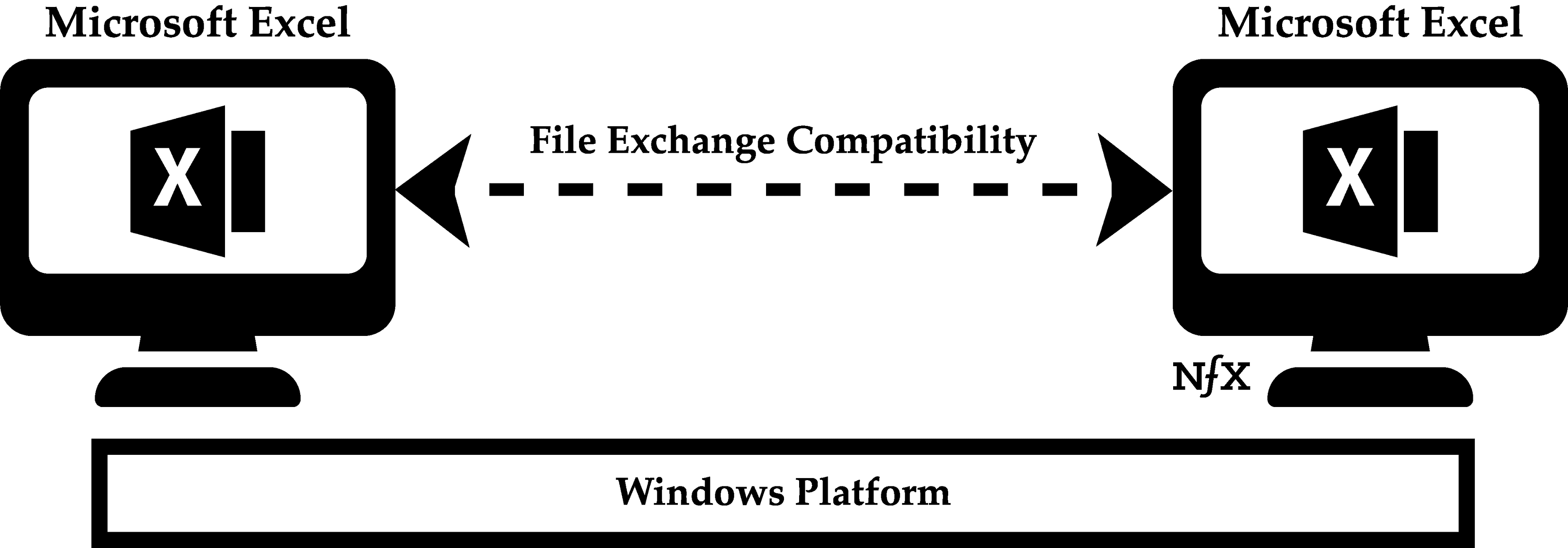

36. Switching Costs

“Switching costs refer to the costs in time, effort, or money that arise when you switch from using one product to another incompatible product.”

When switching costs are high, it tends to create customer lock-in because the customer has more of an incentive to stick with the same supplier throughout their life cycle.

37. Embedding

“Embedding directly heightens switching costs as part of the process of user adoption — due to the depth of your integration into a customer’s operations.”

Embedding is accomplished by integrating your product directly into customer operations so the customer can’t rip you out and replace you with a competitor without incurring significant costs in time, energy, or both.

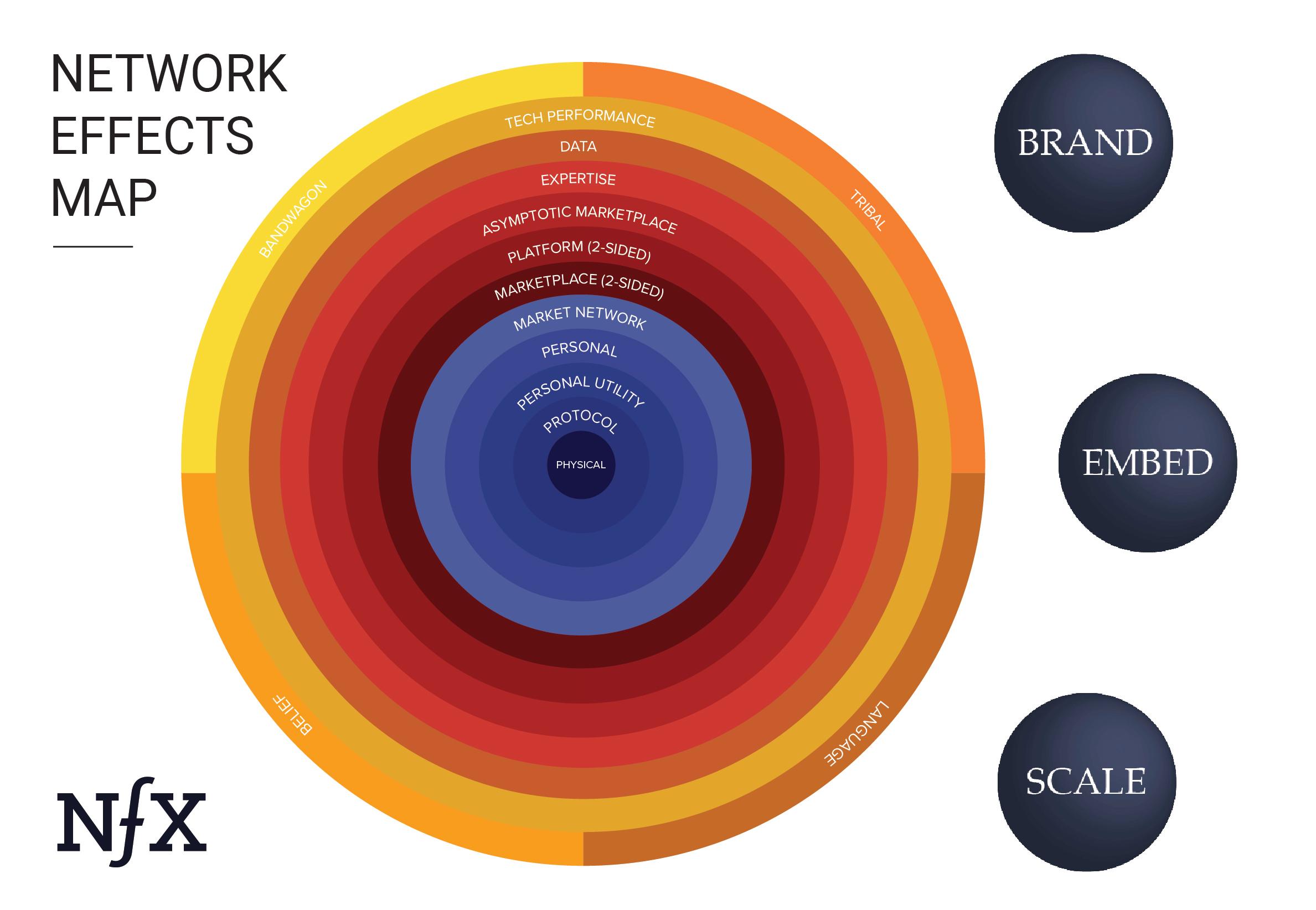

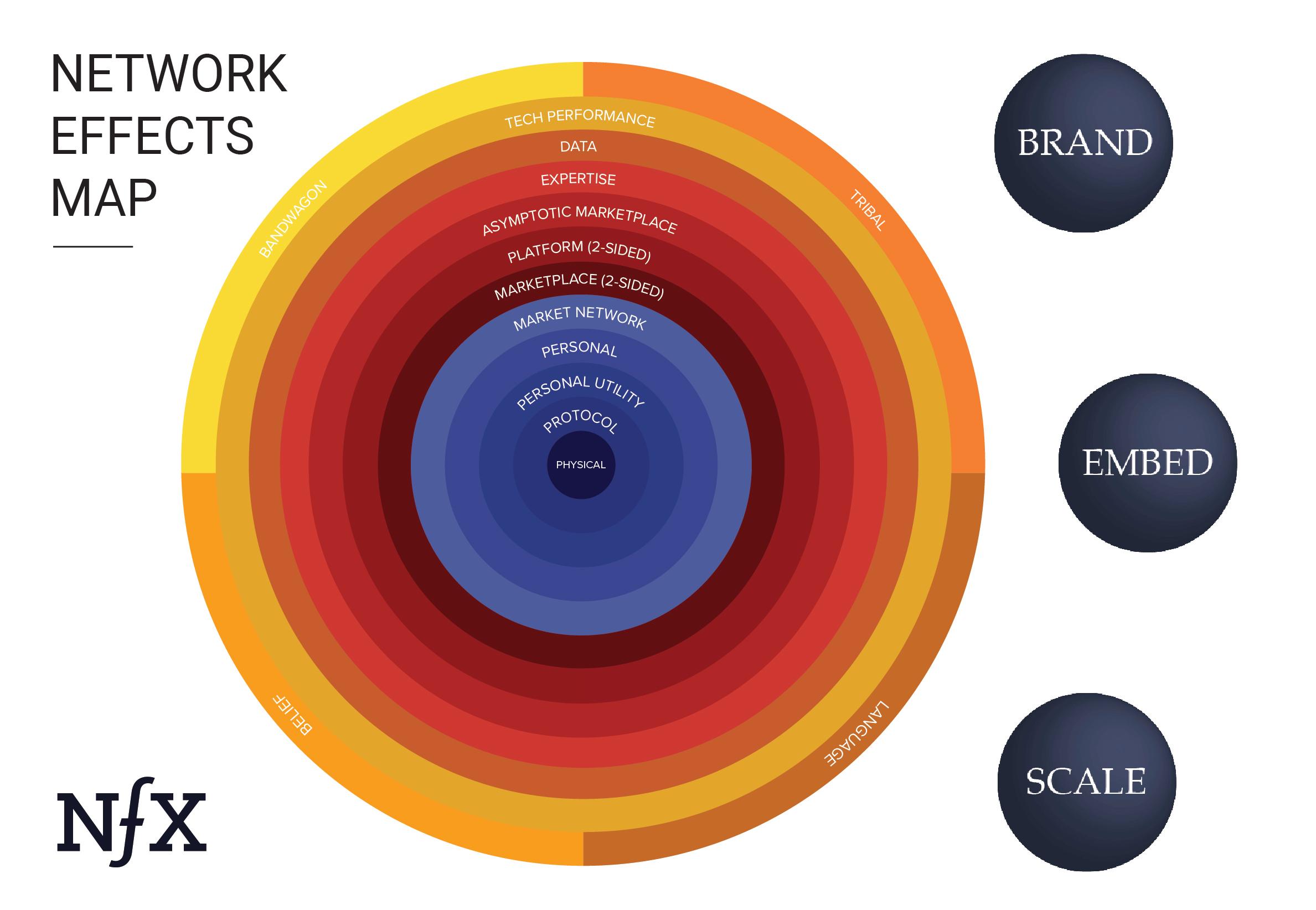

Network Effects

Network effects have been responsible for 70% of all the value created in technology since 1994. Founders who deeply understand these 16 mental models will be better positioned to build category-defining companies.

38. Network Effects

“Network effects occur when a company’s product or service becomes more valuable as usage increases.”

By this definition, network effects seem deceptively straightforward. But when you take a closer look, you start to notice that different types of networks are very different in how they behave. As a result, not all nfx are created equal — some are stronger and tend to produce more value than others.

Different types of nfx are stronger or weaker than others, and they each work differently. They’re listed as follows in order of strength:

- Physical (e.g. landline telephones)

- Protocol (e.g. Ethernet)

- Personal Utility (e.g. iMessage, WhatsApp)

- Personal (e.g. Facebook)

- Market Network (e.g. HoneyBook, AngelList)

- Marketplace (e.g. eBay, Craigslist)

- Platform (e.g. Windows, iOS, Android)

- Asymptotic Marketplace (e.g. Uber, Lyft)

- Expertise (e.g. Quickbooks, Salesforce)

- Data (e.g. Waze, Yelp!)

- Tech Performance (e.g. BitTorrent, Skype)

- Tribal (e.g. Yankees, Harvard)

- Language (e.g. Google, Xerox)

- Belief (currencies, religions)

- Bandwagon (e.g. Slack, Apple)

39. 70% of Value, From 20% of Startups

“Network effects are the single most predictable attribute of the highest value technology companies .”

Our three-year study shows that nfx are responsible for 70% of the value created by tech companies since the Internet became a thing in 1994. Even though they are only a minority of companies, companies with nfx end up creating the lion’s share of the value.

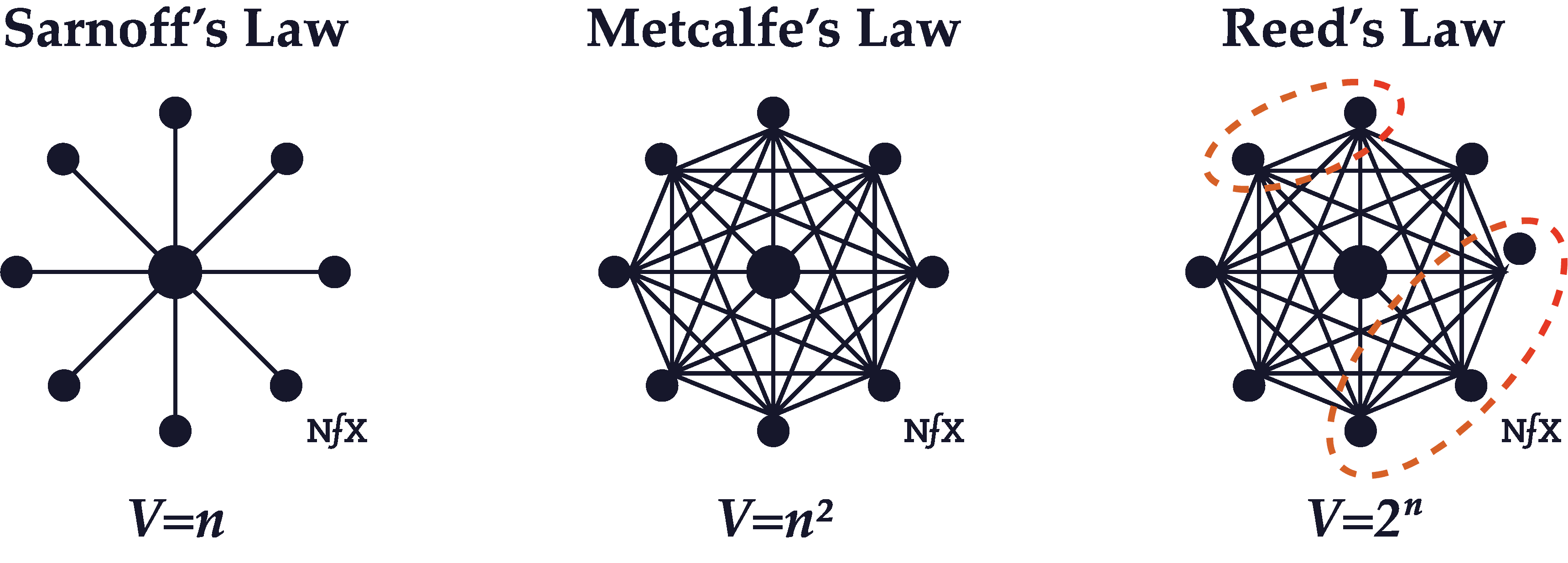

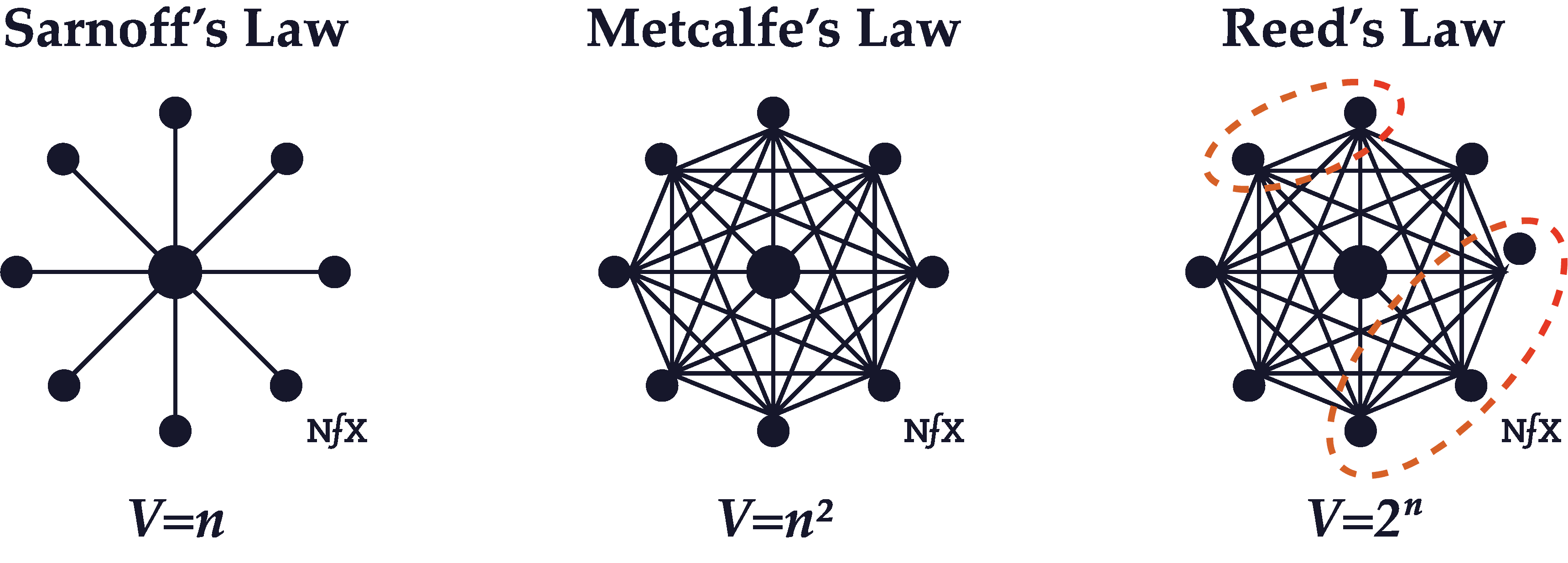

40. The Network Laws

“The value of a network can be expressed mathematically with the volume, density, and clustering of users.”

David Sarnoff was a titan of broadcast era radio and TV, who led the Radio Corporation of America (which created NBC) from 1919 until 1970. It was one of the largest networks in the world during those years. Sarnoff observed that the value of his network seemed to increase in direct proportion to the size of the network — proportional to N, where N is the total number of users on the network.

As it turned out, Sarnoff’s description of network value ended up being an underestimate for some types of networks, although it was an accurate description of broadcast networks with a few central nodes broadcasting to many marginal nodes (a radio or television audience).

More commonly, the value of a network is thought to be proportional to the number of connected users squared (N^2). This is now known as Metcalfe’s Law.

However, in 2001, an MIT computer scientist named David Reed went even further, declaring that Metcalfe’s law actually understated the value of a network. He pointed out that within a larger network, smaller, tighter networks can form.

Reed believed that the true value of a network increases exponentially (2^N) in proportion to the number of users, much faster even than what Metcalfe’s Law described. We now call this Reed’s Law.

41. Direct Network Effects

“The strongest, simplest network effects are direct: increased usage of a product leads to a direct increase in the value of that product to its users.”

The direct network effect was the first ever to be noticed, back in 1908. The Chairman of AT&T at the time, Theodore Vail, noticed how hard it was for other phone companies to compete with AT&T once they had more customers in a given locale. He pointed this out in his annual report to shareholders, writing that:

“Two exchange systems in the same community, cannot be… a permanency. No one has use for two telephone connections if he can reach all with whom he desires connection through one.”

Vail noticed that the value of AT&T was mostly based on their network, not their phone technology. At the time, it was a revolutionary insight. It showed that even if a new telephone was clearly superior to their old phone on a technical level, no one would want the new telephone if they couldn’t use it to call their friends and family.

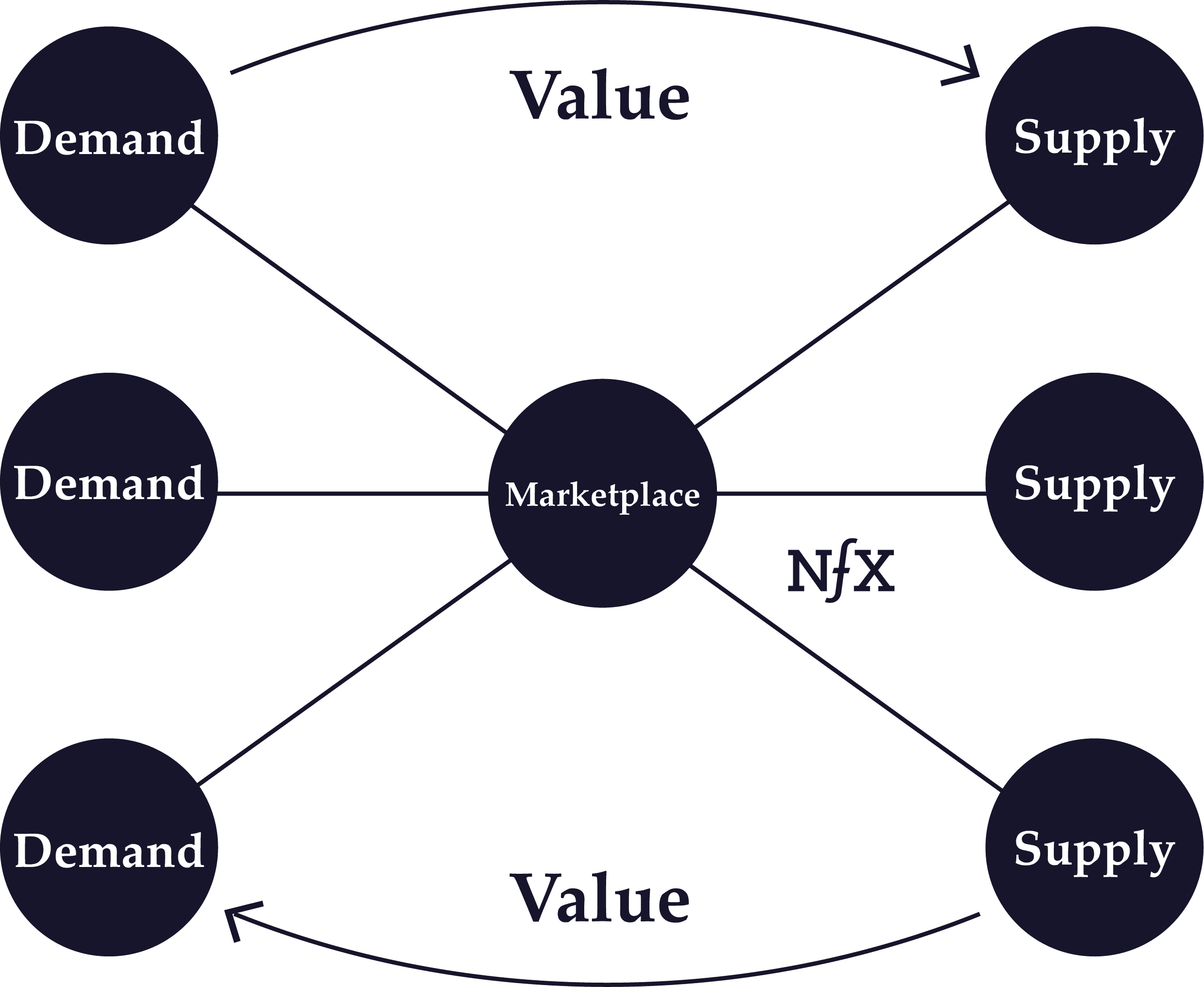

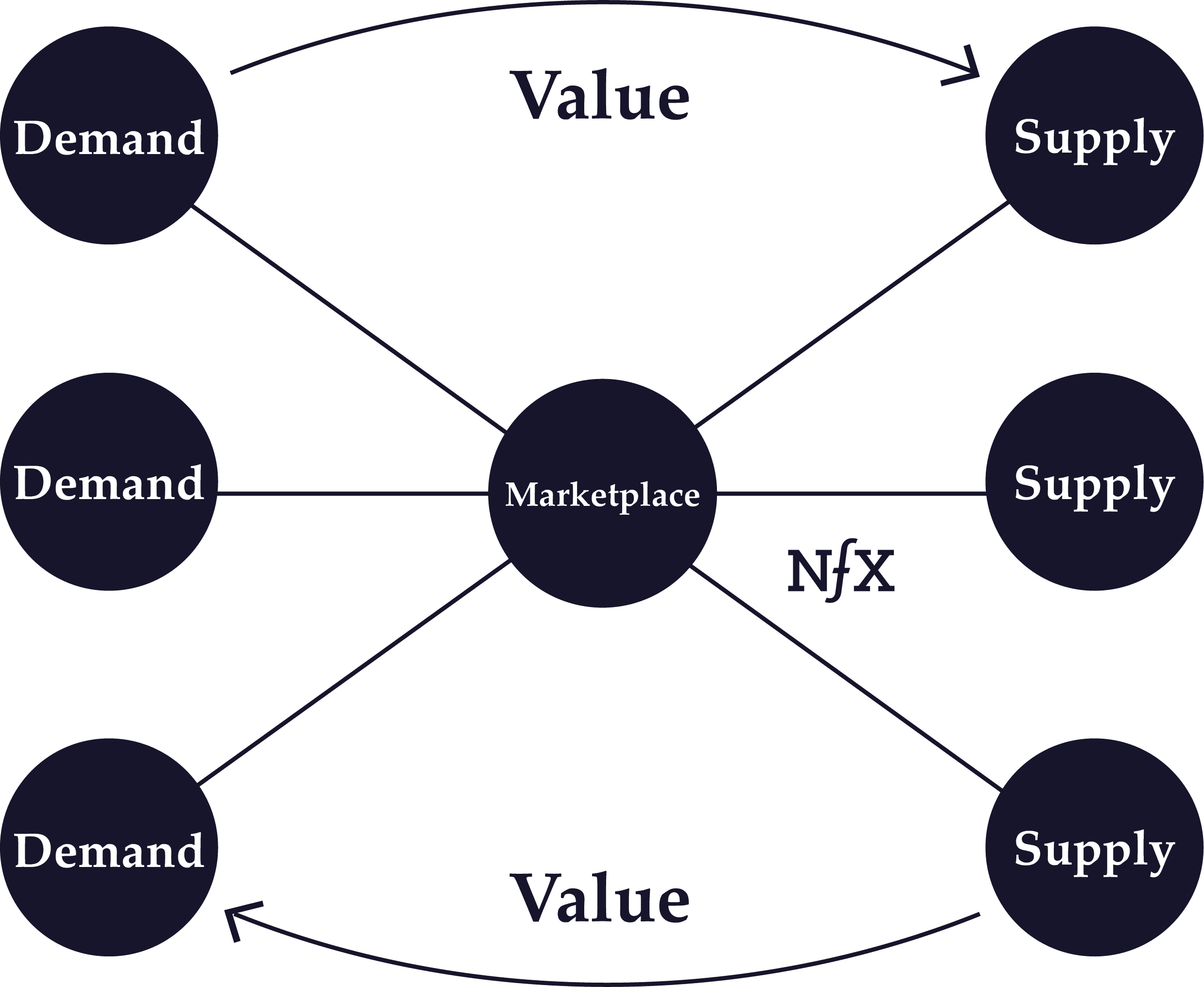

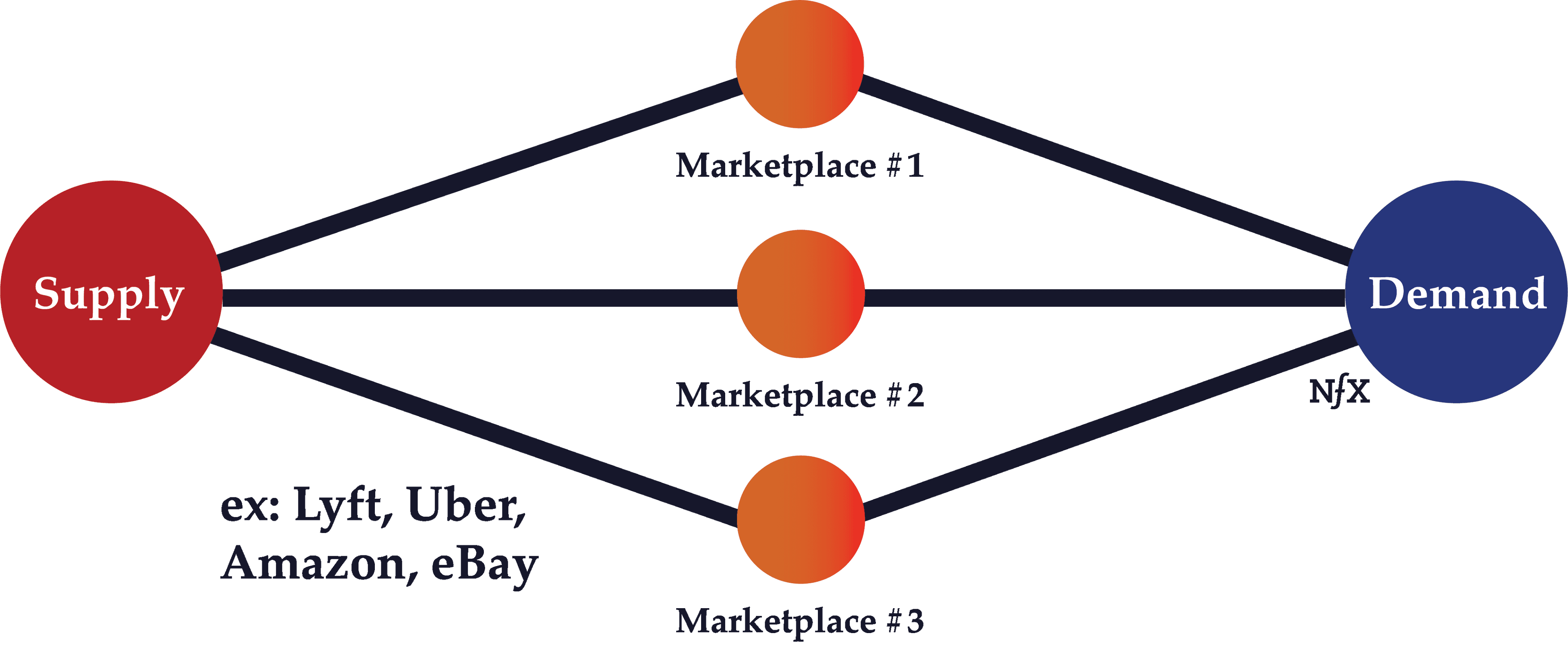

42. 2-Sided Networks

“2-sided networks have two different classes of users: supply-side and demand-side users. They each come to the network for different reasons, and they produce complementary value for the other side.”

They are often called “indirect network effects” in academic literature. However, we think this is misleading since 2-sided networks can involve both direct and indirect network effects.

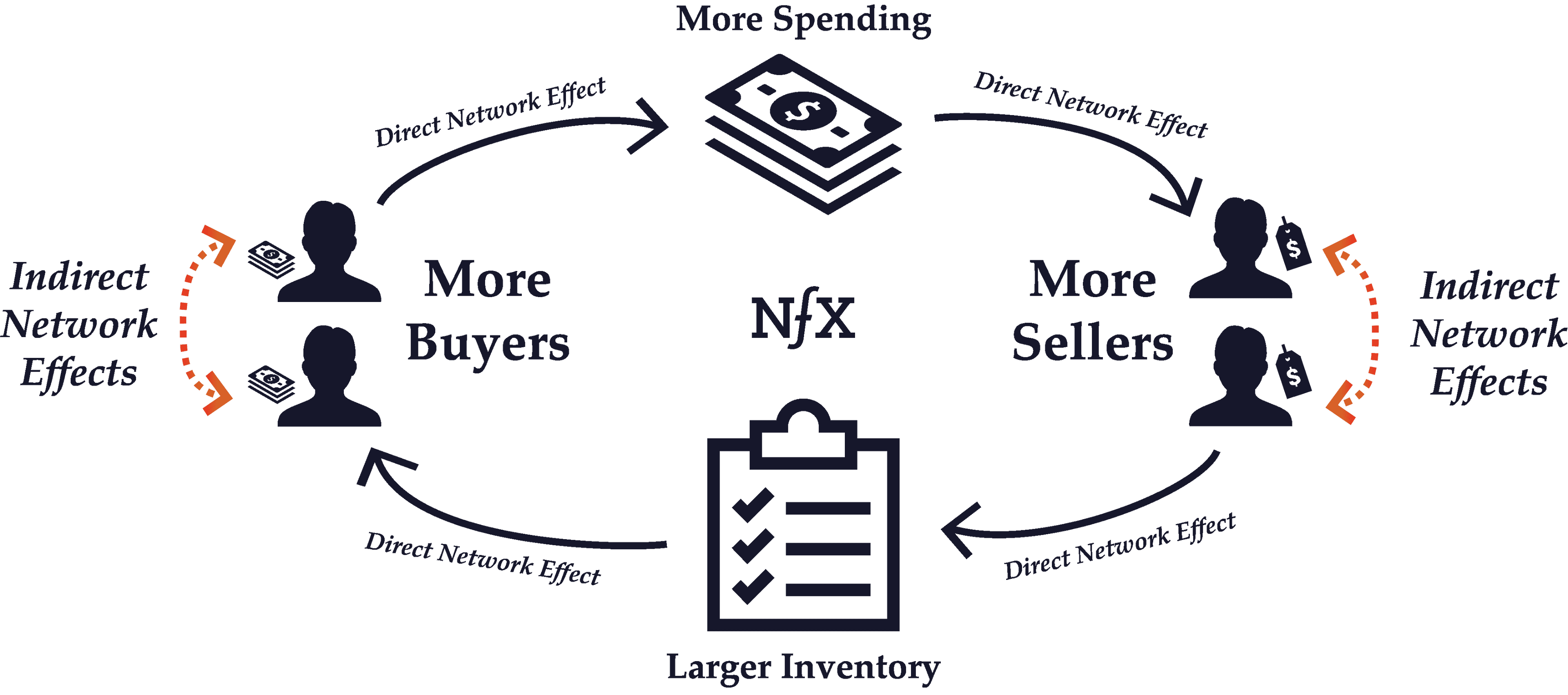

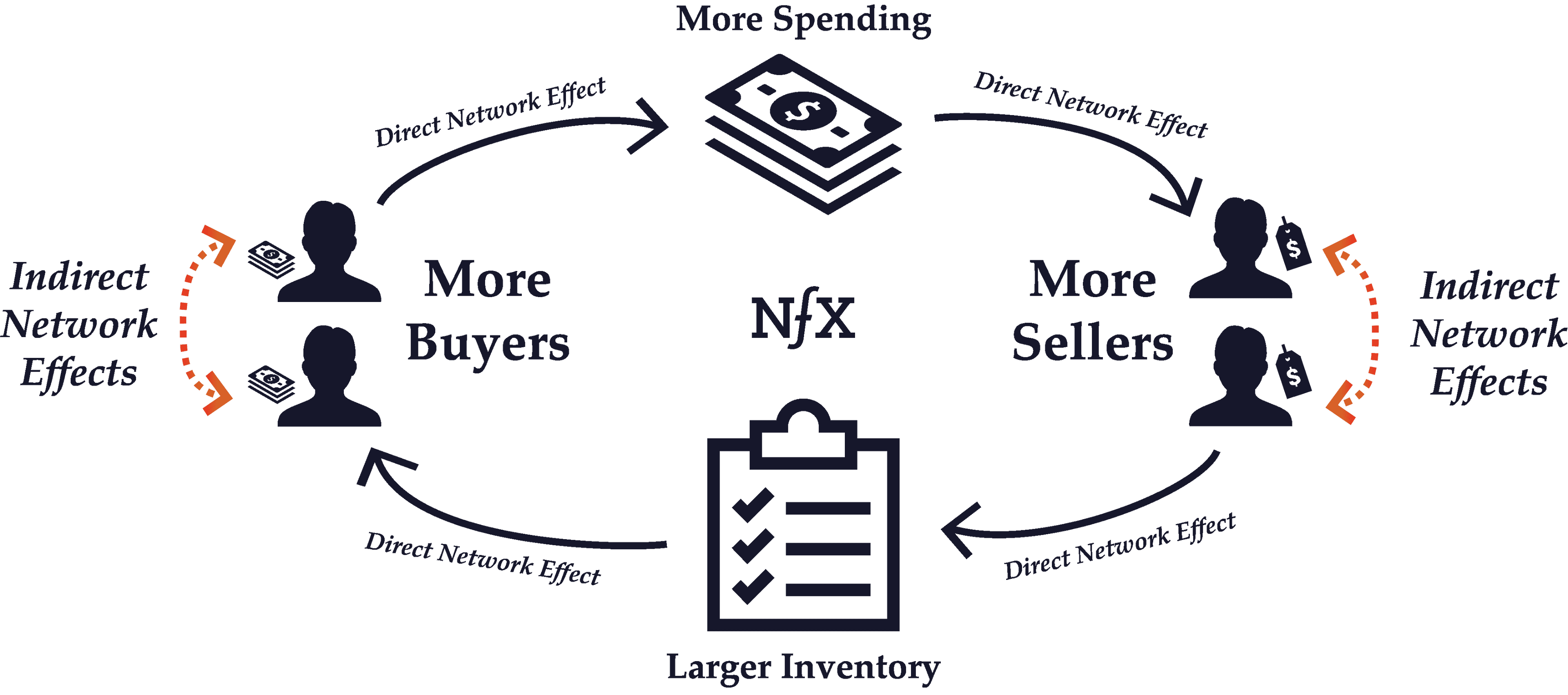

It’s relatively simple to see how each new supply-side user in a 2-sided network directly increases the value of the network for demand-side users, and vice versa. For instance, each new seller (supply-side user) on a 2-sided marketplace like eBay directly adds value for buyers (demand-side users) by increasing the supply and variety of goods. Likewise, every additional buyer is a new potential customer for sellers.

It’s more complicated when we look at how same-side users interact. Most of the time, users on the same side subtract value directly from each other. For instance, core sellers on eBay create more competition for other sellers. More Uber passengers at rush hour mean surge pricing. Both are examples of negative direct same-side nfx.

At the same time, indirect benefits usually end up outweighing those direct negatives. The fact that there are many sellers in the marketplace attracts the buyers to be there in the first place. And that is ultimately more valuable for the sellers, even if they have to sell at more efficient prices. The same is typically true on the buyer side.

This positive indirect effect of 2-sided networks has been discovered and rediscovered throughout history. In the late 1600s, for instance, all the violin makers moved to work and sell their violins on the same street in Venice. Although the proximity of the competing violin vendors drove down prices, it was worth it for the suppliers as a group because it was more important for them that people in the market for violins would take their business to that particular street, not some other street in some other city.

43. Social Network Effects

“Social network effects work through the psychology and interactions between people. This happens when people add value to each other by influencing them to think or feel differently.”

Networks are nodes and links. With a landline telephone system, it’s easy to see the physical phones and wires connecting them.

However, there is an unseen network among people, where our physical bodies are the nodes, and our words and behaviors with each other are the connections. These are the original networks, if you will.

Like digital network effects, these social nfx can help create more value in your product for users the more people use it. People add value to each other by influencing them to think or feel differently. By providing triggers and confidence to use your product. By reinforcing their choice to continue using your product.

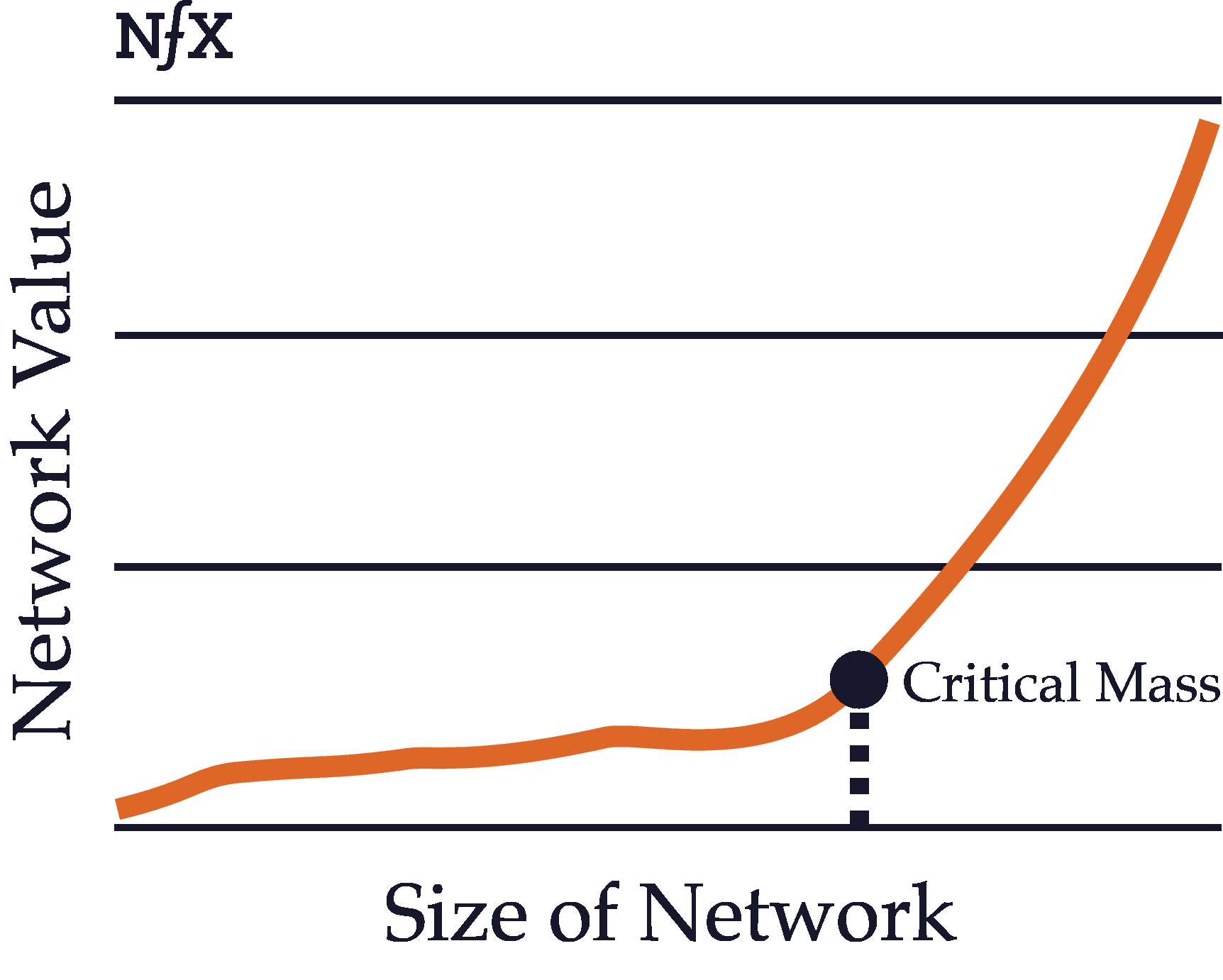

44. Critical Mass

“The critical mass of a network refers to the point at which the value produced by the network exceeds the value of the product itself and of competing products.”

Critical mass can happen at different times depending on the type of the network.

In nuclear physics, the minimum amount of fissile material needed to create a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction is known as critical mass. The idea is that, in complex systems, moving beyond a threshold can suddenly unleash powerful, self-sustaining change.

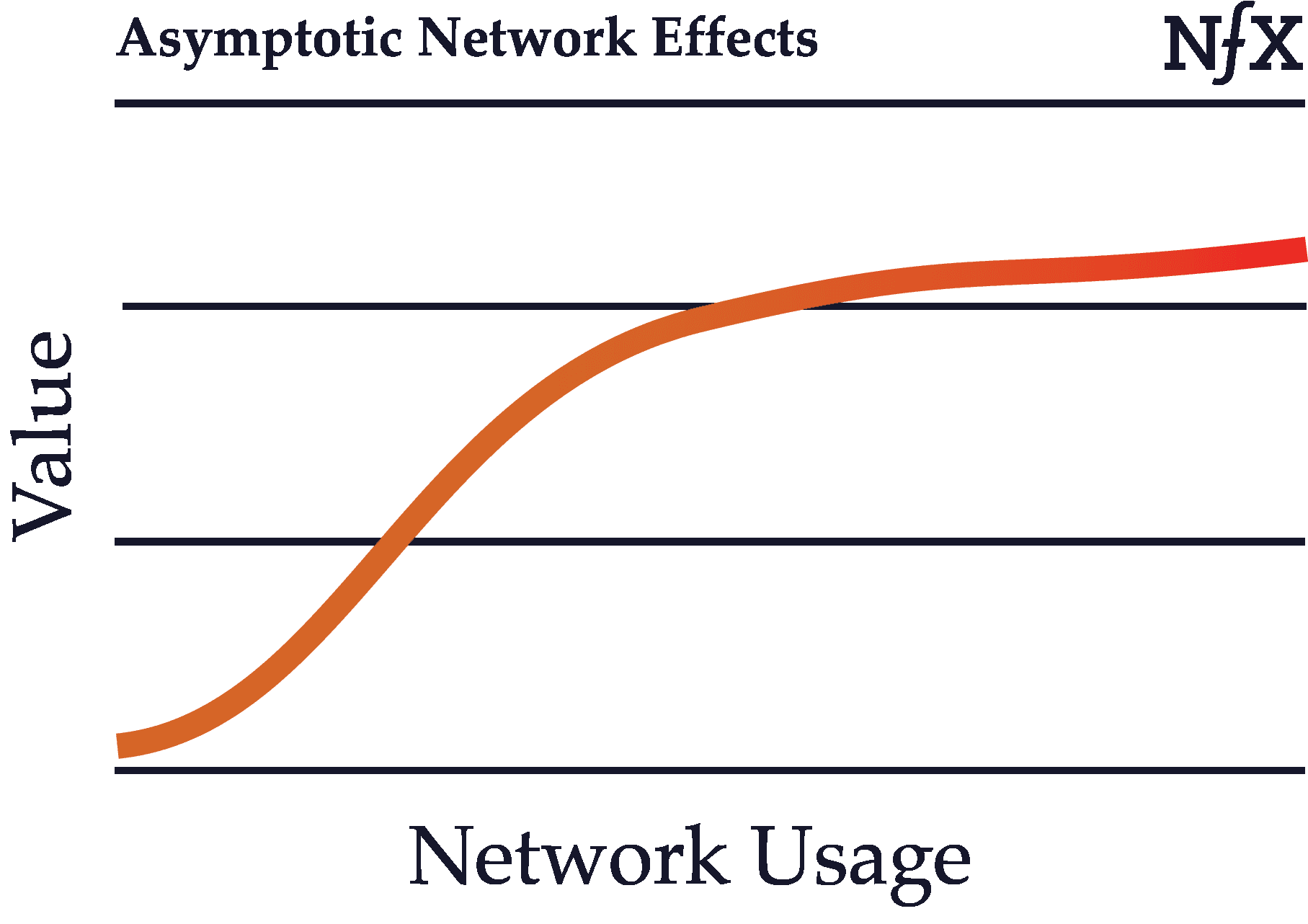

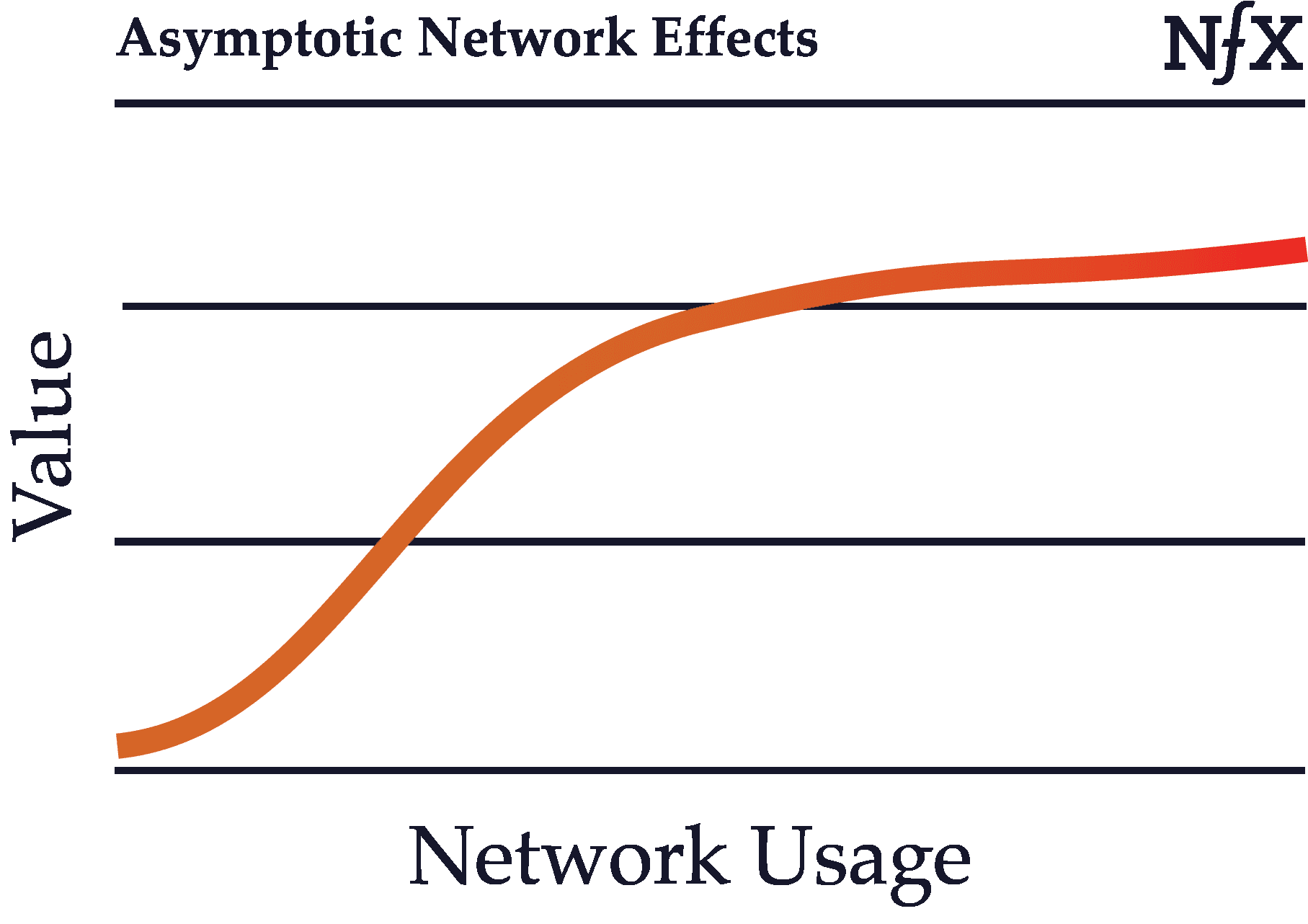

45. Asymptotic Network Effects

“Asymptotic network effects are network effects with diminishing returns.”

Recall the basic definition of network effects: as usage of a product grows, its value to each user also grows. In some cases, however, network effects can start to weaken after a certain point in the growth of the network. Growth in an asymptotic network, after a certain size, no longer benefits the existing users.

46. Same-Side Network Effects

“Same-side network effects refer to the change in value that occurs for users on the same side with the addition of users on that side.”

Same-side network effects are direct network effects that occur on the same side of a multi-sided (2-sided or N-sided network).

47. Cross-Side Network Effects

“Cross-side network effects are direct network effects that arise from complementary goods or services in a network with more than one side.”

As opposed to indirect network effects, cross-side network effects refers specifically to the direct increase in value to users on one side of a network by the addition of users to another side.

48. Indirect Network Effects

“Indirect network effects occur when the value of a network increases as a result of one type of node benefitting another type of node directly, but not directly benefiting the other nodes of its same type.”

Same-side nodes indirectly benefit each other because they create an increased incentive for complementary users on the other side of the network to use the network, which in turn benefits all the nodes on the same side.

49. Negative Network Effects

“Negative network effects can happen in two ways: network congestion (increased usage) and network pollution (increased size).”

In some situations, more network usage or greater network size can actually decrease the value of the network, leading to negative network effects.

50. Single-Player to Multi-Player Mode

“Single-player products increase their value to the user at a linear rate. Multiplayer, networked products can become more valuable at an exponential rate.”

Whatever you choose, it’s important to always be finding ways to switch your product from single-player mode to multi-player as soon as you can. If you do that, instead of having to deliver all the value to your customer yourself, you can set up a flywheel and have your customers create value for each other.

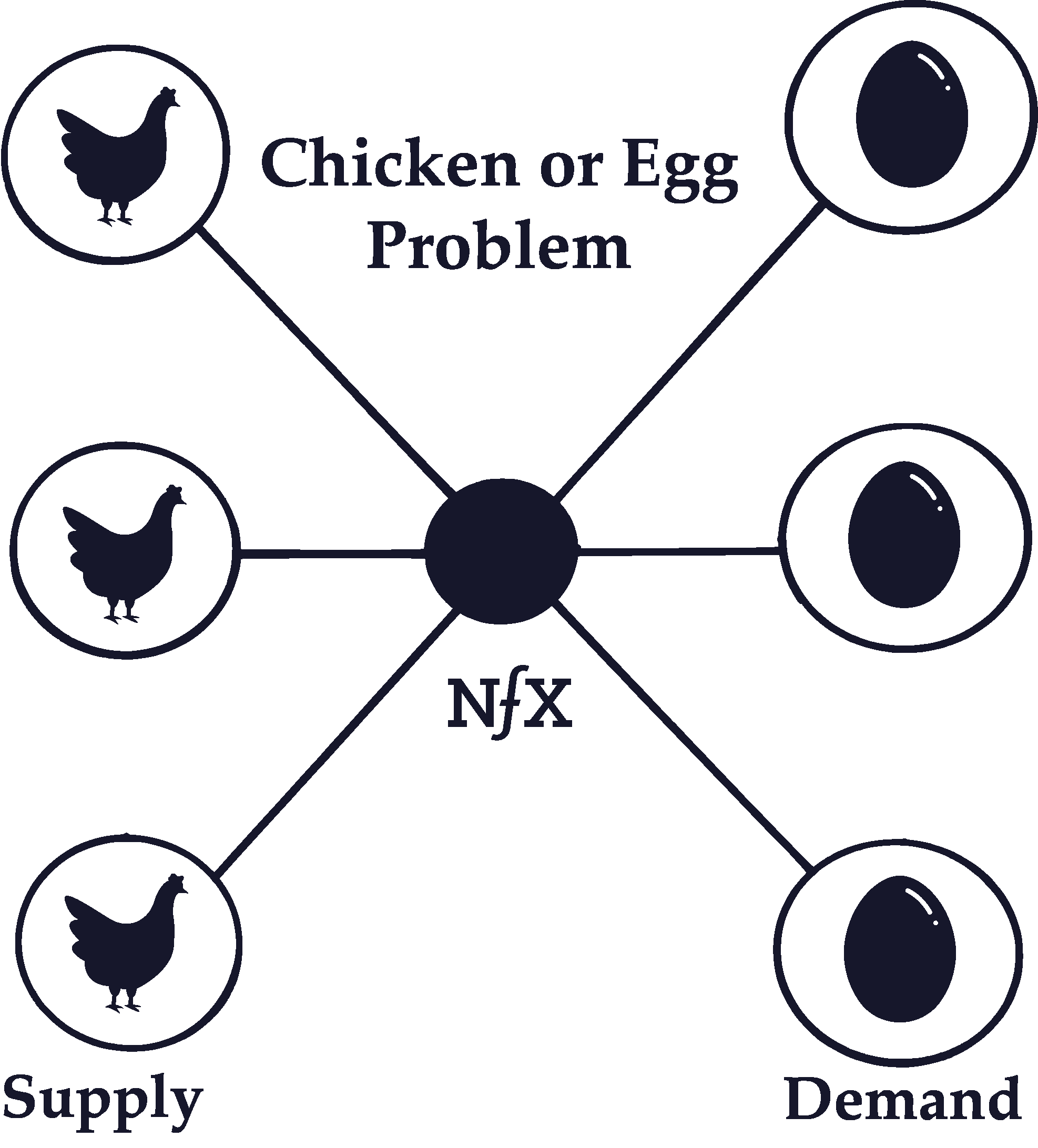

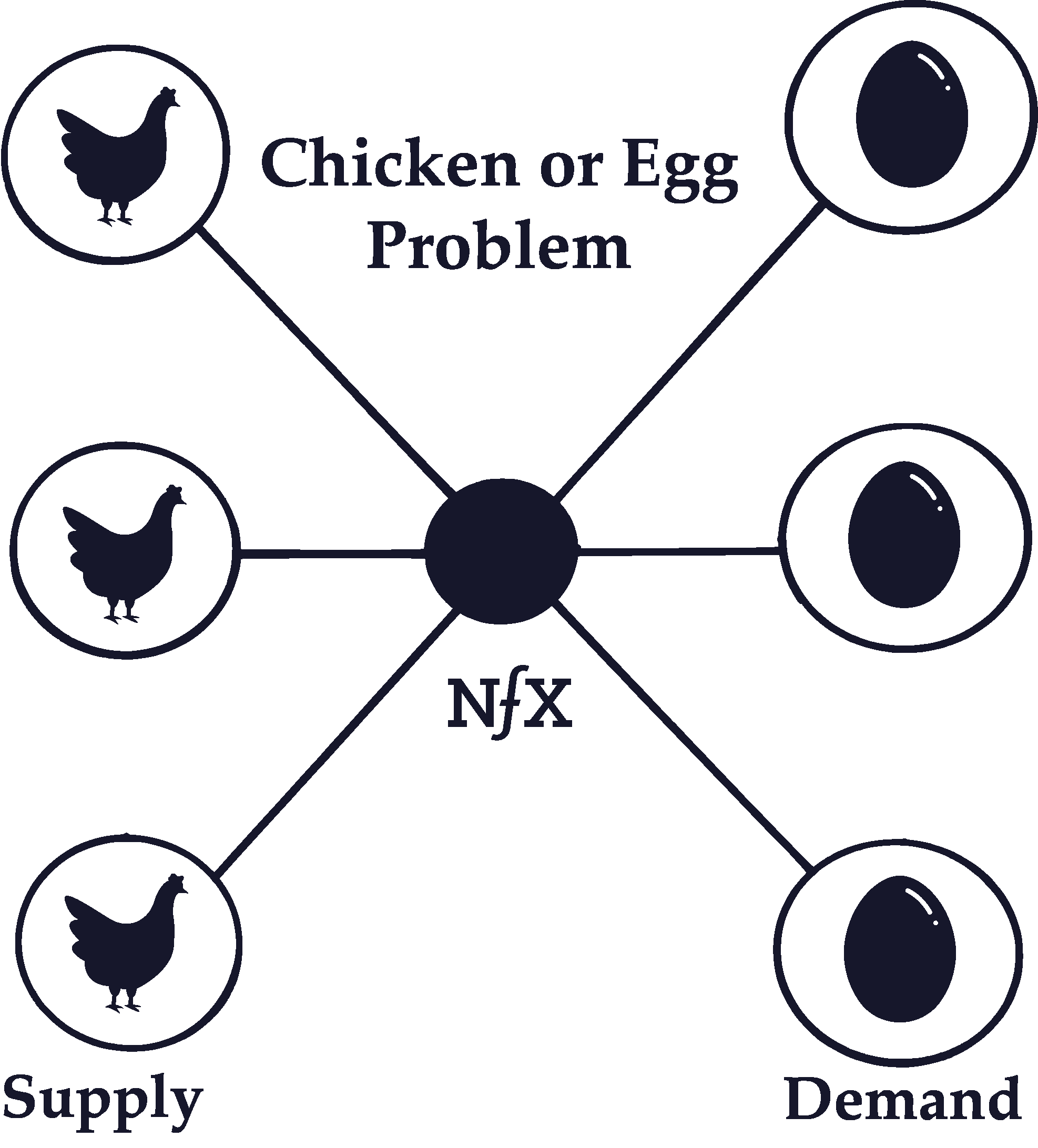

51. Chicken-or-Egg Problem

“The chicken or egg problem refers to the problem of getting enough critical mass to trigger a positive feedback loop.”

If the people on a network produce the majority of value for other users, how do you get the first users to join?

52. Multi-Tenanting

“Multi-tenanting occurs when there are low costs or no costs to simultaneously participating in competing networks at the same time.”

One big weakness in marketplaces and platforms arises from the phenomenon of “multi-tenanting.” People can sell their products on eBay and Etsy at the same time. Landlords can list their apartments on Craigslist and Trulia, and renters can check both marketplaces to browse for inventory. It’s hard to lock out competition from new entrants when the members of your network can use competing networks as well as yours without a penalty.

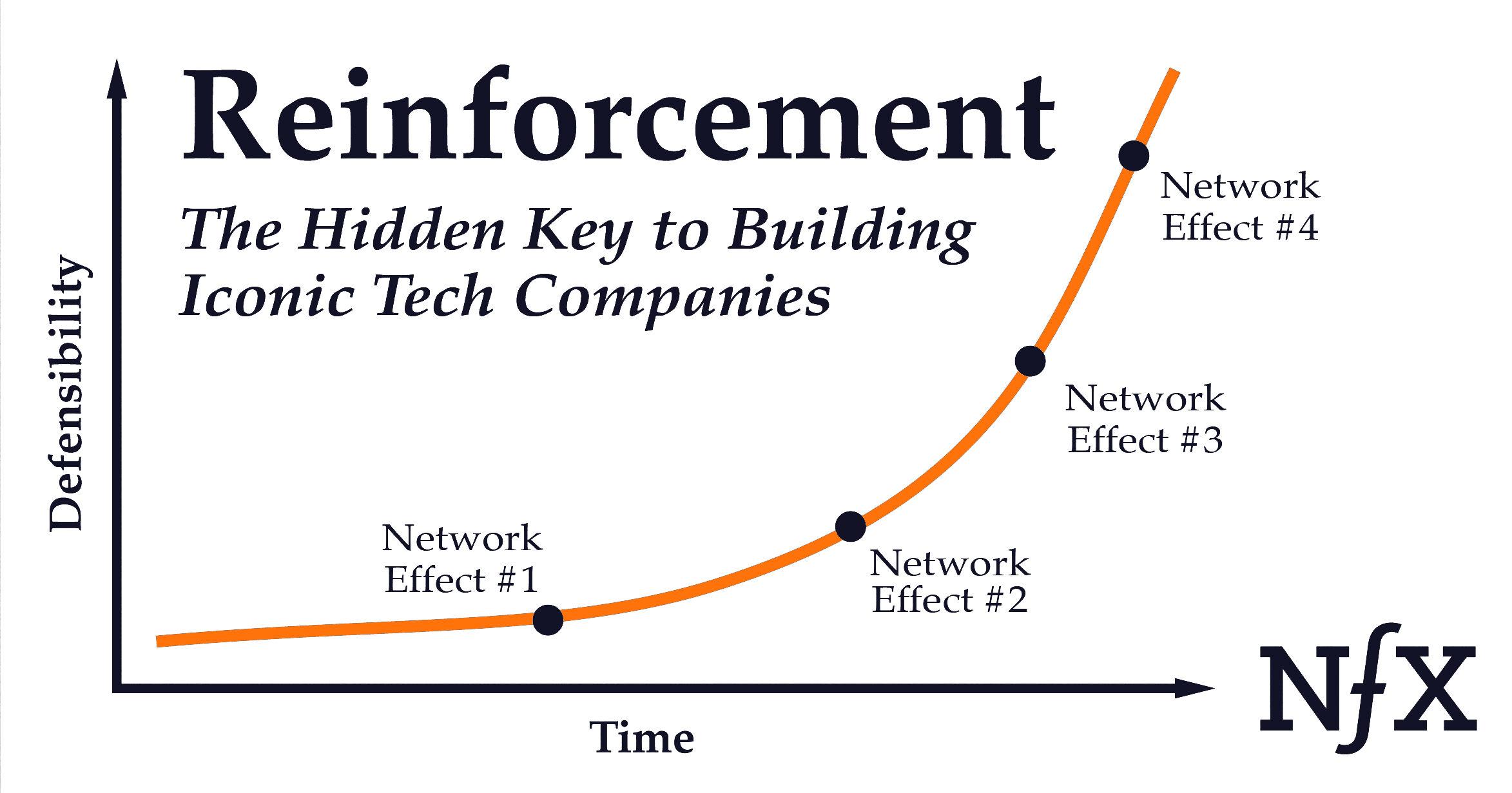

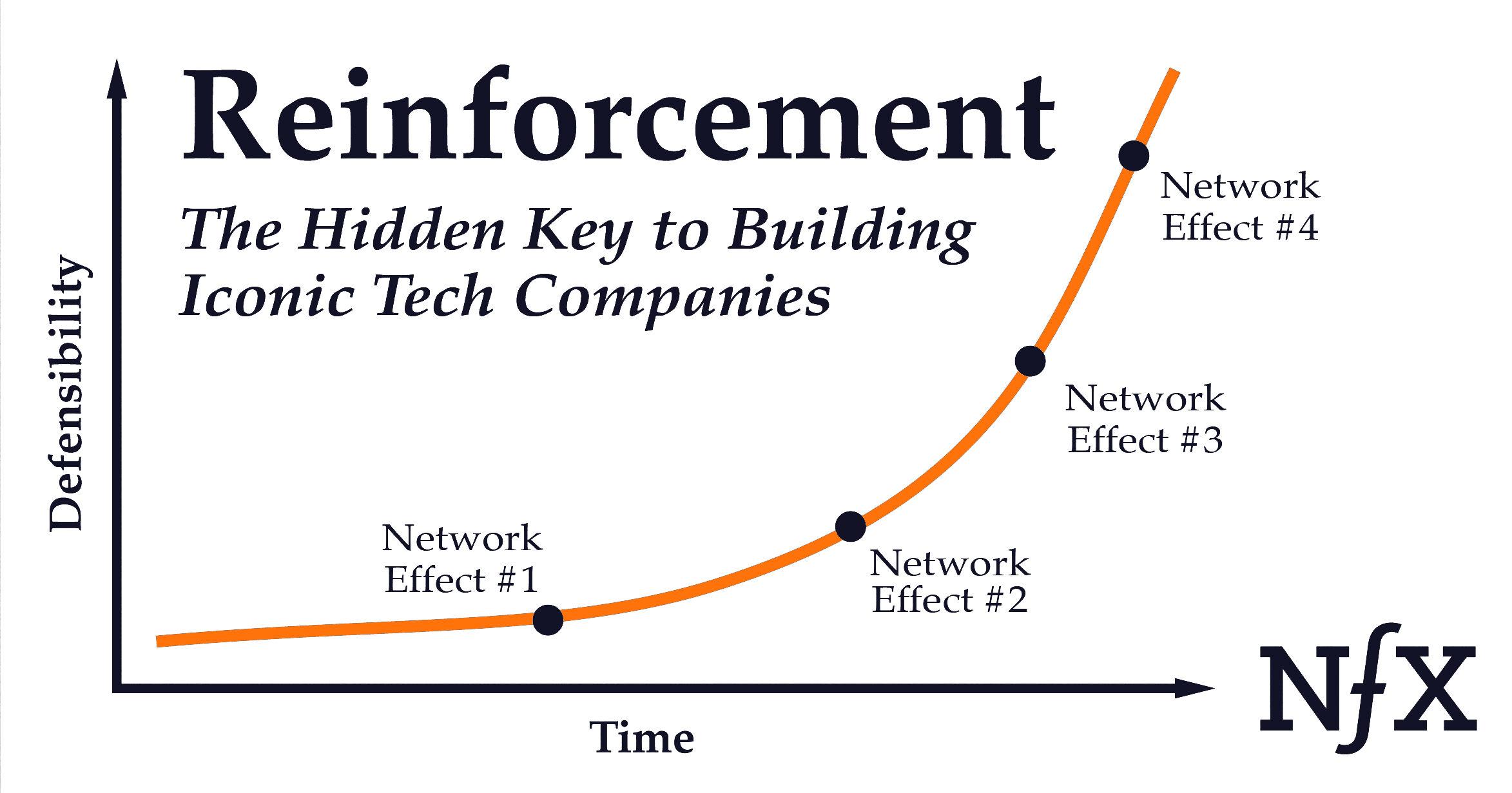

53. The Network Effect of Network Effects

“The sooner a company starts to reinforce, the greater its chances of success.”

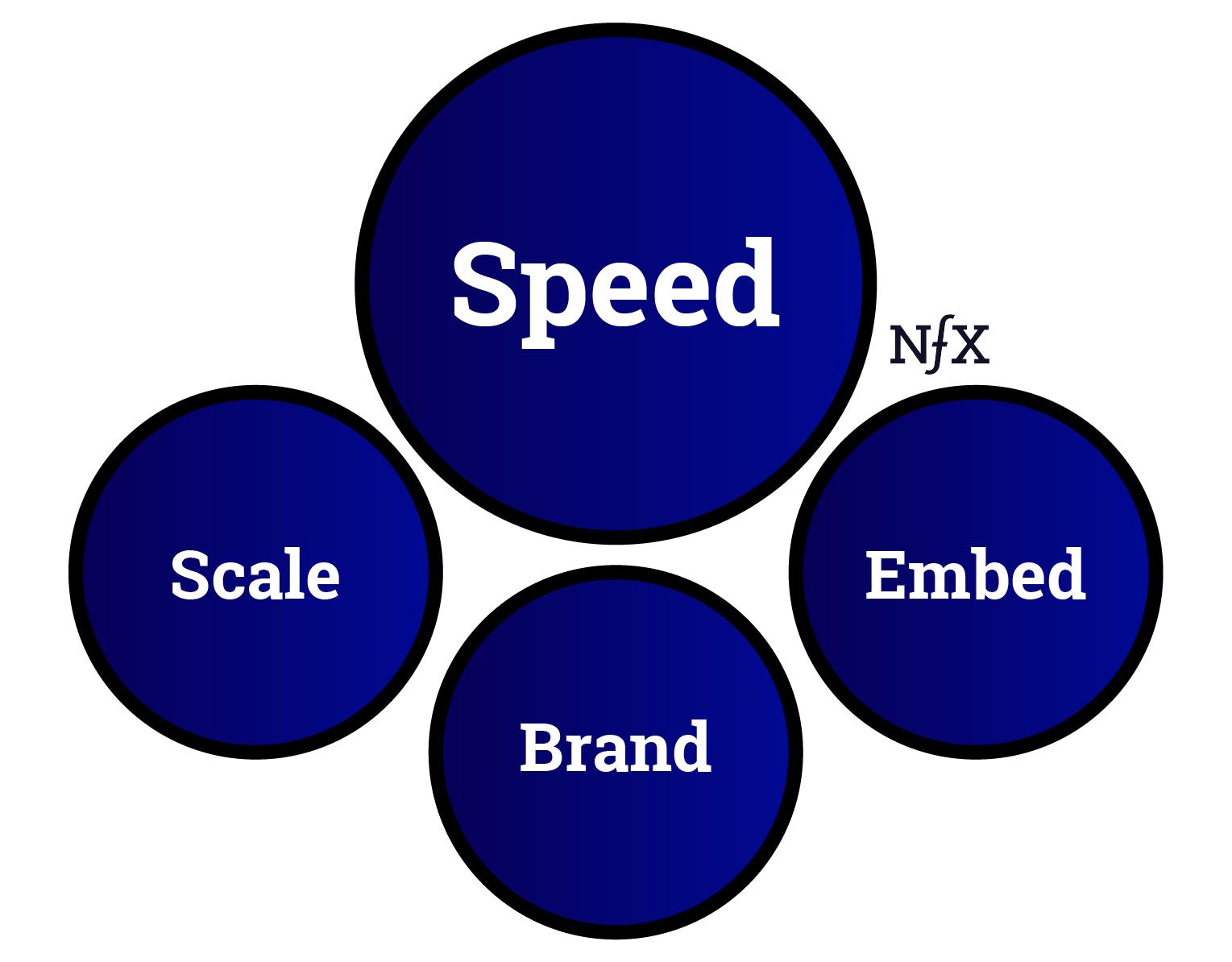

The idea behind reinforcement is this: whenever a company adds a new defensibility — either scale, brand, embedding, or network effects — its existing defensibilities become even more powerful. On top of that, reinforcement makes it easier for that company to add further defensibilities — leading to compounding returns.

Every iconic company to come out of Silicon Valley in the last 25 years has done the same three things:

- Product-market fit. “Right idea, right time”

- Rapid growth. Scale aggressively (Reid Hoffman calls this Blitzscaling)

- Reinforcement. Build overwhelming defensibility

Any type of defensibility will have a reinforcement effect on all the others, but network effects have the most dramatic impact. This is why companies that start out with core network effects — network effects that are integral to a company’s core business, not arising from features added later — are the easiest to reinforce. It’s also why we think of reinforcement as the network effect of network effects.

Note that all of these defensibilities continually reinforced and empowered the others, as in the following model:

Defensibility (personal nfx) x Defensibility (scale) = Defensibility (Facebook as a whole)

Reinforcement compounds.

See Part I of this article with 48 mental models for Founder Skills (12), Decision Making (4), KPIs (6), Culture (9), Company Building (9), and Market Disruption (8).

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.