In 2019, NFX company Incredible Health announced a $15 Million Series A led by our friend Jeff Jordan at Andreessen Horowitz. NFX participated in the round, along with Obvious Ventures and Precursor Ventures. Today, CEO & Co-Founder Iman Abuzeid breaks down the complicated (and often convoluted) process of fundraising and makes public her lessons for the Founder community on what it takes to raise venture capital from top-tier VCs.

In September 2019, the company I co-founded, Incredible Health, announced a $15 million Series A round led by A16z. We’d first received seed funding from NFX, and we sought them out because of their expertise in marketplaces and network effects. James Currier introduced us to James Joaquin of Obvious Ventures who led our seed round, and when we were ready to raise our A, James introduced us to Jeff Jordan. We also received Series A term sheets from other top VCs in the world, but had to select only one due to each VC’s ownership requirements.

The biggest lesson Founders should realize is that traction alone is rarely sufficient to raise venture capital from VCs of that caliber. Consider that Incredible Health has a huge vision of a hiring marketplace for hospitals and nurses that solves the U.S. nursing shortage, and aims to be the category-defining, market-leading company in healthcare labor. The hiring gap for nurses is 3x larger than the engineering shortage and recruiting tools and processes have barely changed since the 1980s and 1990s. This has created a multi-billion dollar market opportunity. We also had an impressive roster of customers from brand-name hospitals like Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and Stanford Healthcare. And we had strong traction with these customers who were witnessing real results – cutting the average time to fill permanent nursing jobs from 90 days to 30 days.

All of this indicates a confluence of opportunity that NFX likes to call “fast-moving water”.

But even with all this traction, I’m not sure our fundraise would have been successful without a strong process – something most Founders don’t realize or get access to. This essay lays out what I learned from fundraising and the process that emerged. My focus here is on raising for a Series A, because that’s my experience thus far, but many of the lessons learned likely translate into Series B and beyond.

Do you really want to raise venture capital?

Before you begin raising, consider and understand the pressures and expectations. If you raise money from venture funds, they will expect rapid growth and most likely will want to be heavily involved with the management of your company. Venture backers will also expect you to hire quickly and scale up fast in many or all aspects of your business. Is that what you and your co-founder(s) want? If not, you might want to look to raise another form of financing or simply use your revenue to fuel growth.

There is a wide spectrum of vehicles, from convertible notes, to venture debt, to standard revolving lines of credit, or use your revenue. Venture equity is the most expensive of the bunch, but venture firms increasingly provide their portfolio companies with lots of business help — in hiring, marketing and PR, strategy, and business development. The bank providing you a line of credit will not take those steps. Consider all of these questions before you definitively decide to raise money from venture capitalists.

Surprising lessons

Fundraising had many surprising learnings for us.

One of the biggest was that traction, even strong traction, is not enough to spur action. Instead, a huge vision and story, and FOMO (fear of missing out) are the strongest forces for accelerating your fundraising process. Once you incite FOMO, it is powerful and you should use it wisely and deliberately. More on that later in the post.

We had so much going for us — traction, product-market fit, a huge TAM. But without treating our raise as a rigorous process, I am not certain we would have achieved nearly as good an outcome – and we may not have been able to raise money at all. We got dozens of rejections, changed our deck dozens of times, and sifted through hundreds of pieces of advice.

Making sure you have the right rationale for fundraising

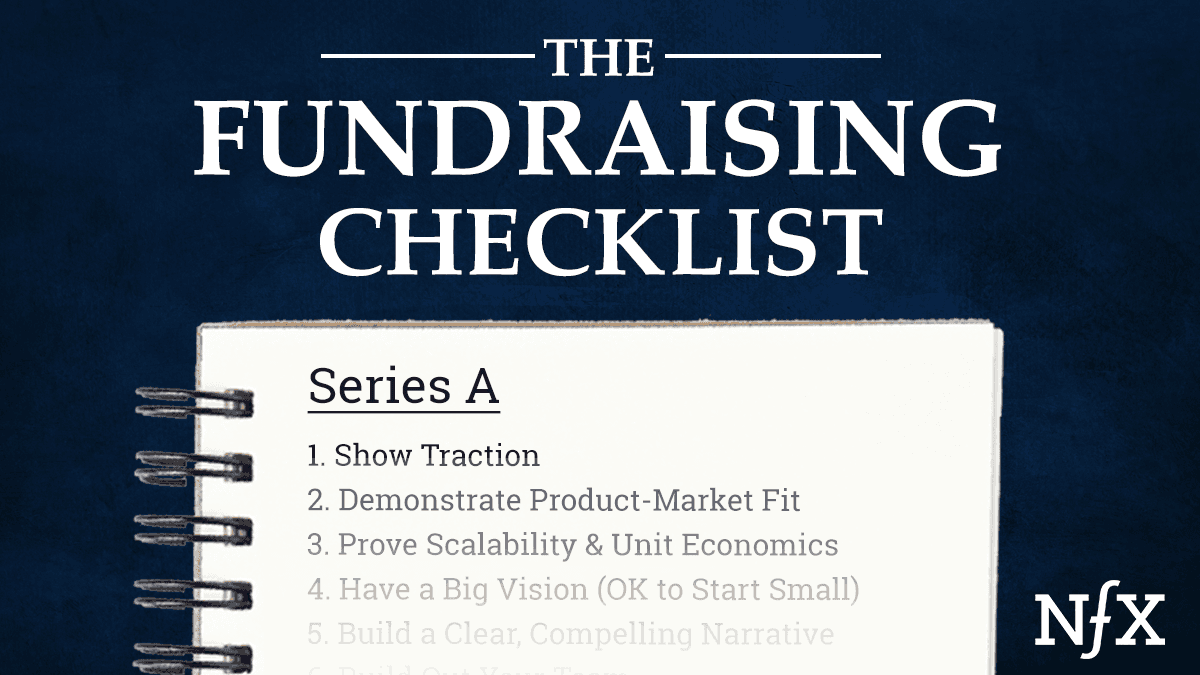

A16z’s Marc Andreessen listed two reasons to raise venture money: you either have a killer idea that is only partially validated and need capital to get to product-market fit, or you have product-market fit with real customers and real revenue and need capital to grow and expand.

Either is a good answer. If you are seeking product-market fit, you could frame your raise as a seed round. This sets expectations appropriately and allows you room to build your product and seek validation from the market. If you have product-market fit, then aim for a Series A.

However, the distinction between the two has gotten blurry. Companies can raise a “super seed” of $5-10 million, while Series A raises can be anywhere from $6 million to $50 million, depending on various factors. Whatever the case, make sure you understand which of the two rationales you occupy. And if you can’t clearly identify either — if you are post-seed but don’t have product-market fit, for example — then don’t raise.

The Two Components of a Strong Raise

We knew pretty early on we were going to raise. I am an entrepreneur at heart and I wanted to grow a business, fast. I had no interest in building a business that might be lucrative for me personally but did not have the scale to make a difference in the world. With that in mind, let’s separate the fundraising process into two parts: the process, and the pitch.

In my experience, the proper breakdown of effort and time spent is 30% process, 70% pitch.

Here’s why: If your pitch is not going to knock their socks off, if you cannot communicate a big vision, then even if you build out the smartest, most thoughtful process of chasing fundraising you will fail.

In reality, though, you have to be amazing at both. Failing to create a strong process limits the pool of potential investors who will hear about you and also reduces your chances of landing with a top-tier fund and a partner that you really want to work with.

The Fundraising Process

There were two key ingredients in our fundraising process: timing our raise, and identifying the right investors.

Timing your raise

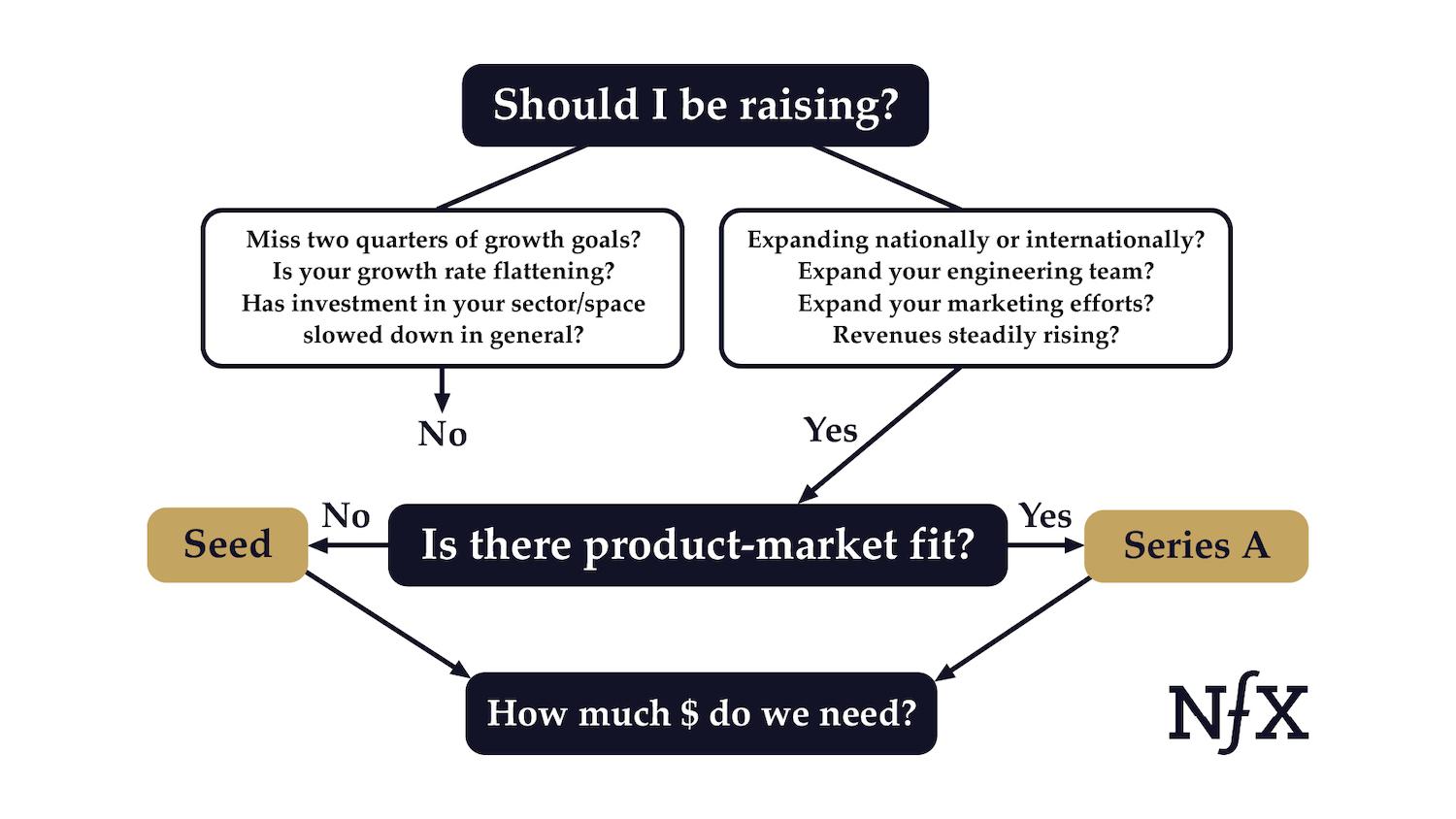

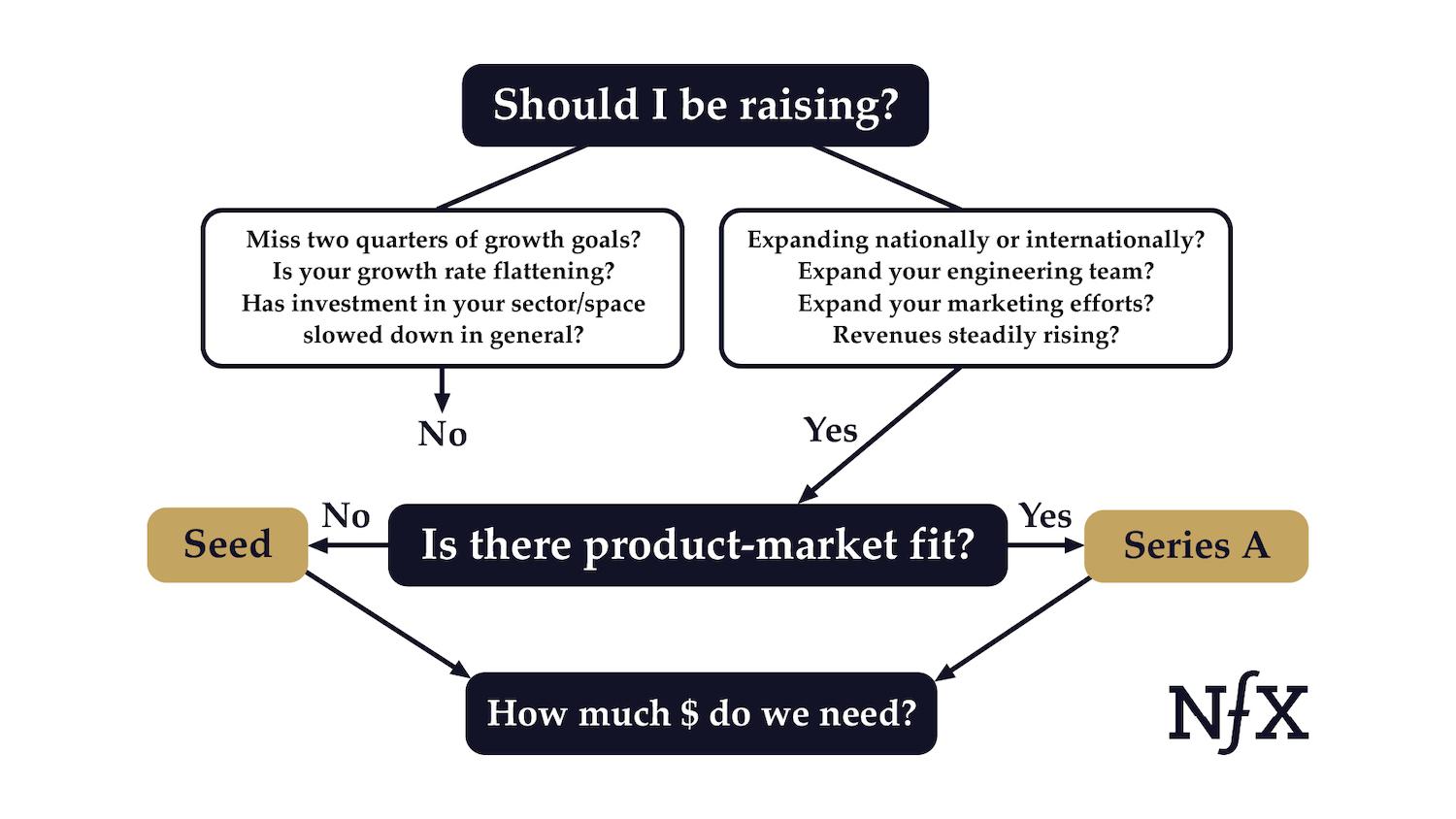

When you decide that you want to raise, you should have a reality check to make sure that you are positioned to do so, or have strong reasons to want money.

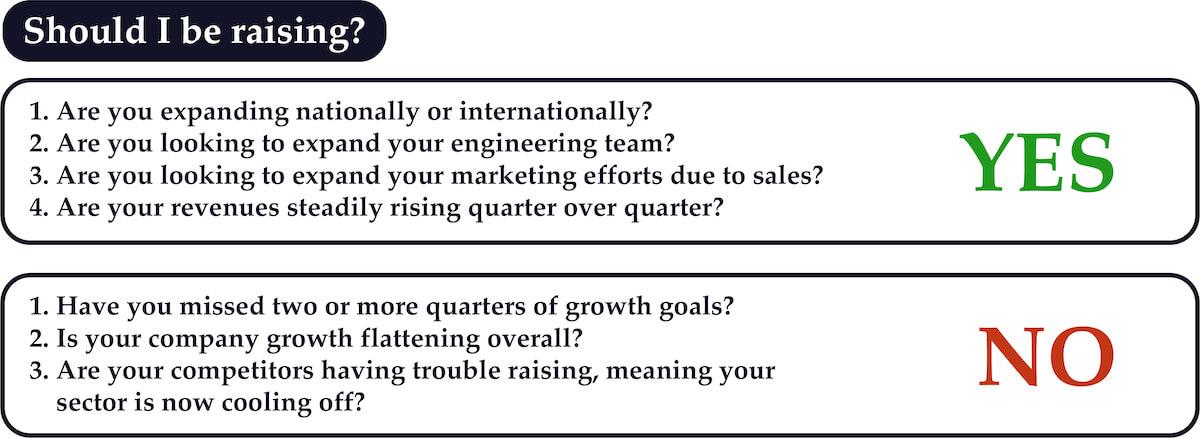

Fundraising is too much of a time sink to pursue if your probability of successfully fundraising is low. Some key triggers that I thought about, and that CEO friends who have raised mentioned to me, as good indications that it’s time to raise include:

- You want to expand nationally or internationally due to market demand and because your product is working and churn is low.

- You want to expand your engineering team to accelerate product development, and to build features and integrations users are asking for.

- You want to expand marketing efforts because you have a repeatable sales cycle and need more in the top of the funnel to fuel sales growth.

- Your revenues are steadily rising month over month, or quarter over quarter.

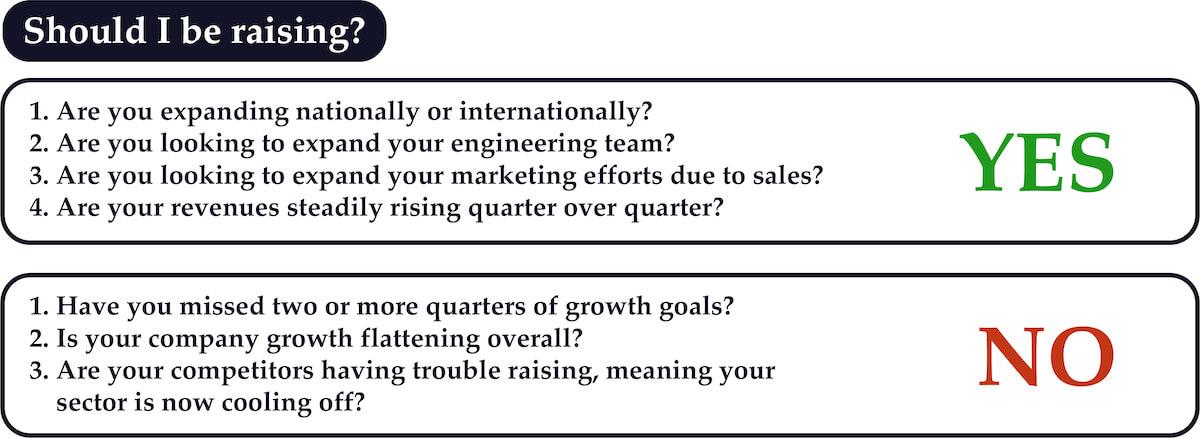

Some indications that it might not be the right time to raise include:

- You just missed two quarters of growth or sales numbers. This is a red flag to investors.

- Your growth rate is flattening out.

- Your space just cooled off. You know this because two competitors raised less than the market expected.

These are just a few of the triggers to look for. Above all, be very intentional about the timing of when you raise, because you want the fundraising to happen quickly and successfully. To do that, you need to have all the right ingredients in place, and strong momentum in your business. With so many startups fundraising at any one time, any question marks will slow down a fundraising process.

Identifying the right investors

Here is the process we followed for identifying investors. We built a spreadsheet for this, as you probably would want to do, with some simple data on how well they fit with our ideal VC funding candidate.

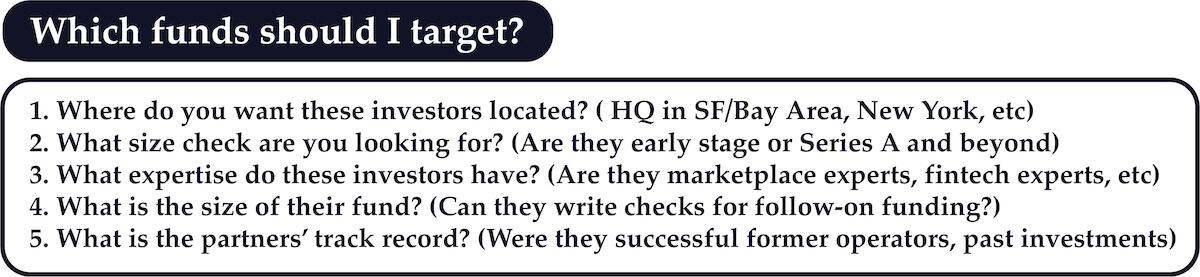

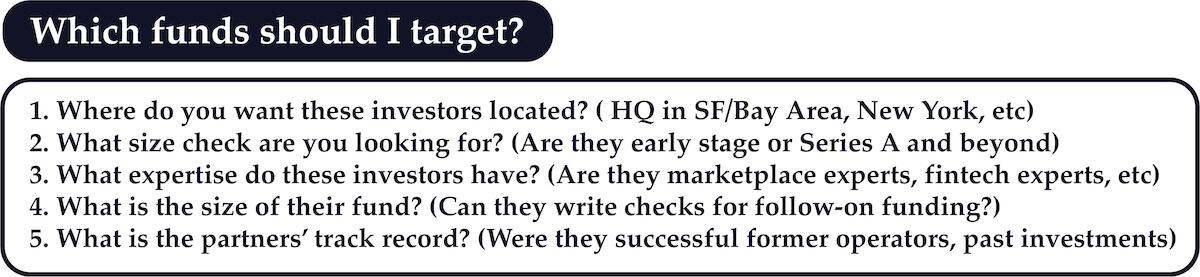

Step 1: Filter based on the criteria that matter to you

Just like a sales team identifying the right potential customers who fit the profile of your product, you want to identify the right potential investors. We considered a number of criteria as important in our screen including:

- Location – we wanted investors in the Bay Area

- Check size – we wanted to be able to raise a decent-sized series A to reduce the need for follow-on funding

- Sector expertise – we wanted experts at building marketplaces so we could benefit from their experience, connections, and talent network

- Fund size – we wanted a lead investor from a large fund so we could have confidence they would be able to easily write checks in follow-on rounds (equally important here is whether the fund is planning to raise another fund for not. You may want that additional fund for follow-on funding).

- Track record – we wanted a lead investor with a solid track record because that signals it’s a good fund with good capabilities, which also would reflect well on Incredible Health.

You may decide other factors are important in your screen, like specific technical expertise (if you are an AI company or a data company, for example) or ability to help with business development (some funds have detailed ongoing programs to introduce their portfolio companies to prospective customers).

Or you may also want a fund that is well-known for being hands-off. Anything that you think is important should go into your screen. We went with the above criteria as our primary screens.

Step 2: Build your fund wish list with tech tools and human recommendations

Once we selected the criteria that were important for us, we used some tools to build our list.

- Signal (built by NFX) is an investor database with lots of screens. It helped us narrow down our options very quickly.

- Crunchbase has information on different funds and the deals they had invested in.

- Pitchbook has the most detailed deal data and valuation info. Both deal data and valuation data were important for helping us screen investors, and later for building out models around how much we should try to raise and at what valuation.

While databases are nice, we also found that human filters gave us some of the best recommendations.

We asked all of our CEO friends and our early investors who they recommended we talk to about raising money. This can be powerful for a number of reasons. You may be connected with unexpected opportunities or learn about things that may not be in the databases yet (for example, if a prominent partner is about to break out and do their own fund).

These human filters can also help warn you off working with funds or VCs that may be difficult to deal with, or simply are unlikely to be a good fit for your needs. Your CEO friends often have a great handle on which VC fund, and which partner, might be the best match.

I’d recommend you build a list of 40 to 50 funds because you should expect a rejection rate well above 90%. Trust me. I’ve lived it.

Also, you will likely be working on getting an introduction into multiple funds at once so you want many irons in the fire. You are not in full control of timing in this step of the process so it’s best to cast a relatively wide net. However, after the introduction is made, you are back in control and can determine when you meet the investor, because they often connect you with their assistant.

Granted, if you have very strict criteria then you may want to narrow it down more. But that also carries the risk of not raising a round. We were fortunate enough to get both the fund we wanted and the valuation and round-size we sought. Not every founder will be so lucky and sometimes you may need to accept a less than perfect scenario.

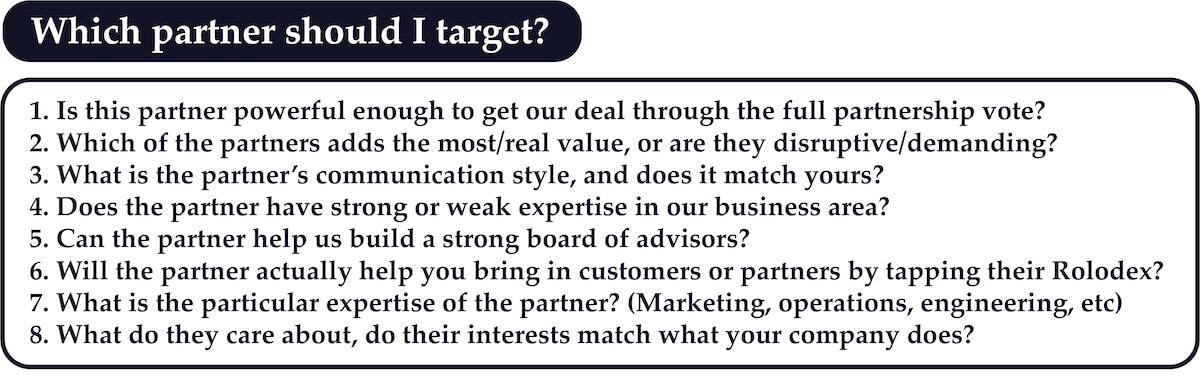

Step 3: Identify the right partners at each fund

For each fund, you now need to identify who would be the best partner for your to seek an introduction.

This is super important. There are complicated and usually hidden power dynamics inside most funds. You can’t judge whether a partner is a good fit for you just from the website or even from news articles about them.

Some partners have more clout to push a deal through than others. Some partners may not be seeking more investments because they are at their deal quota and sit on more boards than they can handle. Some funds have specific ways of performing due diligence that more senior partners can influence but junior partners cannot. With all of this in mind, we considered all of the following angles:

- Is this partner powerful enough to get our deal through the full partnership vote? Or is this a weaker partner?

- Which of the partners adds the most value / adds real value? Which ones might actually be disruptive and demanding?

- What is the communication style of the partner? Does it match ours?

- Does the partner have strong or weak expertise in our business area?

- Can the partner help us build a strong board of advisors?

- Will the partner actually help you bring in customers or partners by tapping their Rolodex?

- What is the particular expertise of the partner? Marketing? Operations? Engineering? What types of expertise map the best to your company’s needs?

- What do they care about? For example, some investors care a lot about network effects. Others are more into robotics or crypto. Do their interests match what your company does or what you need?

Getting this type of intel about individual partners is time-consuming and challenging. But it is absolutely critical, because otherwise you will be walking into a fund blind, and potentially picking a partner that has a lower probability of getting you funded or making you successful down the road.

Another key part of this due diligence process is to start figuring out who can give you a meaningful warm intro to the partner. Venture capitalists are extremely busy. They are bombarded with requests for their time and meetings. Getting a warm intro from a strong connection is invaluable both for getting in the door and also for the halo effect it gives you walking into that first meeting.

Frankly, we didn’t even consider cold-contacting venture capitalists. Our friends and early-stage investors told us it was not a good use of our time.

That lays out the process we developed and ran during our raise. Now, on to the pitch.

The Fundraising Pitch

During the entire course of your raise, our pitch was a work in progress. We changed it dozens of times, which was healthy because we were responding to feedback and learning and iterating.

If you aren’t constantly tweaking your pitch, then you are probably not listening to feedback enough. During our rounds, we customized our pitch deck for each meeting, catering to what we thought would resonate the best with each set of potential investors.

There were core themes and slides that remained the same. But we believed that personalizing was crucial to showing we had taken the time to think about pitching to them as a person.

What to put in your pitch

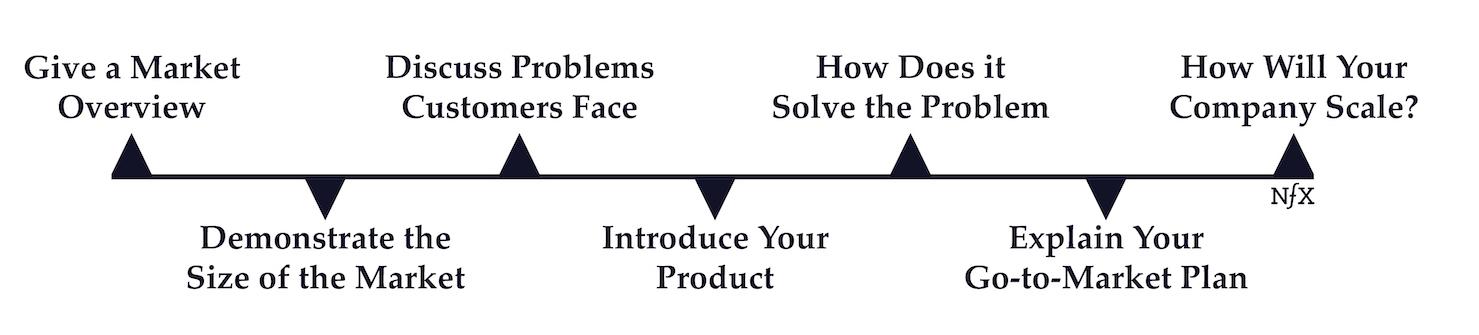

The pitch model we followed (that worked) is straightforward:

- Discuss the market

- Demonstrate the size of the market

- Cover what the problems are that customers are facing in the market

- Introduce your product and how it solves those customer problems

- Explain how you plan to bring your product to market and scale your company

Within this framework, here are some additional guidelines that we picked up in our journey.

Pitch Guideline 1: Highlight the differentiation of your product

Good UX or clever marketing is not sufficient. VCs are looking for technical or really measurable differentiation. Some examples along these lines might be:

- Unique algorithms

- Data network effects / data gravity

- Superior or unique product capabilities that might take a while for competitors to replicate

Pitch Guideline 2: Use good metrics

Ideally, you will have specific metrics that show your traction and strength. The best metrics are:

- Industry appropriate: You should assume that whomever you are pitching will know (or soon find out ) what the right metrics to look at are for your space and expect you to know them, too.

- Demonstrating stickiness: DAU, MAU, time spent in-app, repeat customers, churn rate, NPS, and CSAT are just a few examples of this. Product stickiness and happy customers or users are the best indications you are doing something right.

The Importance of Go-To-Market And Winning Big

GTM is a major buzzword. We were asked about it often during our raise. You should expect this, as well. The more detailed you can be about your GTM, the better. A strong, detailed plan for GTM demonstrates you have thought about how to grow and that you really understand your space.

Now, about winning big. This is probably not news but it’s important to underscore because we got called on this in some of our meetings. A few VCs said we were too “capital efficient.” This means they didn’t see us as having a reason to spend their money or a clear path in our minds and in our presentation to rapid growth.

Never forget that VCs are looking for huge returns. If you can’t show them a path to a billion-dollar exit, they are not interested. For many VCs, they are looking at hundreds of opportunities per month. Few of them will ever get a billion-dollar exit. One billion-dollar exit can literally make their career. So you have to make sure they understand that you are trying to give them that billion-dollar exit.

How To Build Pitch Decks

We used decks as the key prop for our narrative, the visual support for our story. You can do it without them, but it’s hard if you want to tell a compelling story, backed by data and frameworks.

Step 1: Put a relevant number on every slide

We learned an excellent lesson from the NFX team early on: make sure to have a relevant number on every slide, supporting every assertion you make.

Putting something like “We are seeing strong demand for our product” on a slide was not good enough. Instead, we would say “We have seen a 50% MoM increase in inbound leads from hospitals.” Adding the number gives investors confidence that you have done your homework and demonstrates in a more tangible way the assertion you are making.

Step 2: Work hard on your talk track, too

You will convey a lot more information in what you say than what’s in the deck.

In particular, how you explain your product is crucial. I worked on that a ton and got a lot of feedback. I had to hone that ability extensively before we started to make real headway and get investor interest.

Step 3: Rehearse, Rehearse, Rehearse

Practice your pitch with your deck on friendlies. Do this many times.

CEO friends who had recently raised were the most valuable to me. Their advice was the most useful in upleveling our deck and we benefited from what they had learned along their journey. Existing investors are also excellent for practice pitches with a soft crowd.

Use spreadsheets to build a robust financial model

Our second pitch vehicle was our financial model – both P&L and balance sheet – in a spreadsheet. For any financial modeling, this is essential. If you try to do something different, investors will look at you funny.

If you are not good at financial modeling, have someone help you. Any MBA should have the ability to create a decent financial model in a spreadsheet. It shows you are serious about finance and the money side of things and understand the underlying assumptions that drive your business and growth.

You need to have a robust financial model with forecasts going at least three years out, and include your historical financials too. No one expects the forecasts will be accurate. But these forecasts demonstrate what you think the potential of your business is and they also demonstrate basic financial competence.

Be prepared to defend your forecast calculations; know them inside and out. Also, make sure all the accounting terms you use are correct, and that your model passes the sniff test with CFO-types. If you don’t have a CFO or someone that can build a solid financial model (and you aren’t an MBA), it’s worthwhile to hire someone to do this.

Assume you will need to adjust your model over time with feedback. As I mentioned earlier, in our first few pitch meetings, VCs told us we were too capital efficient. “What are you going to do with all the money we give you? Your model doesn’t show that,” they said.

We adjusted our model to demonstrate how we could effectively use all the money we were asking and to have a more ambitious growth-oriented plan. You also want to be very realistic in all your assumptions. Do not put down a $100k salary for an engineer in San Francisco, for example. Unrealistic assumptions will be challenged.

Getting ready to pitch

We had built out a list of VCs we wanted to meet and prioritized them on our criteria. We had worked hard to create a pitch and a deck that we thought would resonate. And we had a financial model. Now it was time to take some meetings. In this section, I’ll cover what we learned in the process of pitching and make some recommendations on the best approaches.

Part 1: The Warm-Up

We warmed up by pitching first to two or three investors that were very low on our priority list. I viewed this as almost like a dry run for job interviews starting with jobs you don’t really want that badly.

There is little risk to you in these pitches. It was helpful to get me in the right mental space for doing pitches. It also helped me hone both my pitch and other skills I learned for pitch meetings.

Part 2: Gathering Feedback

Each VC will have feedback. Some of it may be insanely useful. Other feedback, less so. Gather that feedback closely and use it to iterate and improve your deck and your pitch.

Incorporate language they use that you like. Absorb like a sponge. Sometimes we got feedback that was hard to interpret. In those cases, I talked about it with others on my team and with other CEOs to better understand what the VC wanted or was trying to communicate.

Feedback is not just verbal or via email. In meetings study everyone’s body language with laser focus. Keep track of which slide makes them sit up, when they smile, when their eyes go wide open. Also keep track of negative signals like slumping, looking down, or appearing bored.

Make sure you closely associate these signals with the part of your deck or pitch you were covering at that instant. We took careful notes on this after every meeting. It helped us identify what parts of our pitch and what slides were the most and least effective.

Part 3: Going beyond the KPIs

We had very solid traction, strong revenue growth, excellent customers and a product that both sides of our marketplace raved about.

We quickly realized that traction alone was not going to get us term sheets, let alone partner meetings.

Investors want a really big vision for the future, something they can bet on and something that shows you are trying to build something huge and amazing — a legendary company where the VC is part of that legacy. Traction is required but not sufficient, but having a big vision and a plan to get there is required.

When investors could not see that part of our story easily and clearly, they lost interest. So I can’t restate enough – telling a really big story and having a big vision is essential to raising a healthy round.

Part 4: Using FOMO to drive to the finish line

There were a couple of Tier-1 investors that think independently and made the decision to give us a term sheet independent of the rest of the market. We had heard about FOMO but didn’t understand its power until late in our fundraising process. In the blink of an eye, we saw a rapid increase in Incredible Health from Tier-1 funds. The reality is, we realized, that competition for good deals among Tier-1 funds is just as intense as the competition to raise capital.

Once you are marked as a highly promising startup and the holder of primo term sheets, then you will probably get interest from other VCs who are afraid of missing out on a deal that could make their fund a success.

Once you have it, you can use FOMO to drive a higher valuation, more capital, or lower dilution for your round. But be careful with FOMO.

- Don’t fake FOMO. If you don’t have a term sheet from a top-tier VC, then don’t claim to. If you are called out, you are done.

- Don’t tell investors which VCs have given you a term sheet. You want to keep them in the dark to prevent them from colluding (illegal but does happen)

Once you feel FOMO building, accelerate your process and use it to your advantage. Your goal should be to raise as quickly as possible once you feel FOMO. You can time-box your raise to drive faster decisions, for example. Investors will move quickly when they see something they want. Use the way people respond to FOMO as a filter, as well. You may elect to go with a smaller round and a lower valuation if the partner you want the most made an initial offer and then gets FOMO’d by other funds that you are less interested in for one reason or another.

Don’t Reinvent the Wheel. Enjoy the Ride

I laid out most of what I learned in my fundraising here, which I hope readers find useful.

My sincere wish is to help CEOs and founders save time and effort in building out their fundraising process, in part by leveraging what I learned. This is not rocket science and there is no need to reinvent the wheel.

While fundraising is grueling, it can also be exhilarating and rewarding. You are selling a story and a vision to some of the smartest people in the world. They will ask excellent questions and you will learn from them.

Your network will expand and your storytelling skills will improve. Fundraising is a growth opportunity in more than just one way. It is all part of the journey toward building something that changes the world.

For more information about Incredible Health, visit https://www.incrediblehealth.com/. Follow Iman on Twitter @ImanAbuzeid and Incredible Health at @JoinIncredible.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.