Founders need to learn to build community and tribal network effects around their products. It’s a key skill for nearly every company, and will amplify everything else you do.

If you look at the new online community builders — who are really like CEOs of their companies of 1 — many now have more followers and influencers than traditional media outlets. The technology has given them superpowers. They’re crafting different realities. They are controlling their narrative. This makes community builders new power brokers in society. As Erik Torenberg calls them: “reality entrepreneurs.” Founders can learn those same skills.

Today I talk with Erik about how to build community for this new era. We break down how to give users status and connection, as well as utility and value. When you get this right, you not only build tribal network effects into your product, you build durable relationships with your customers and partners, leading to greater defensibility and thus enterprise value.

Cultural Innovation is Skyrocketing

- Community building is so important right now, not just because people are lonely, but because people are confused. People are lost.

- People often say, “Today is the era of fake news. We used to have this shared reality with three cable channels, we were all on the same page, and everything was great.”

- It’s less that today is the era of fake news and more that it’s the era of an explosion of news. What The Revolt of The Public did is, with the internet and social media, it gave everyone a voice. And guess what? A lot of people have a lot of opinions and also a lot of facts.

- The world is much more complicated than those narratives that those three cable channels led us to believe.

- So, reality, in a very major sense, is up for grabs in many ways. And we’re now seeing more and more entities bootstrap their own reality. People call this community building. It’s actually people defecting their shared sense of mainstream reality that has existed for a long time and creating new ones.

- Trust in institutions is crumbling at the same time the platforms for people to exit their own realities and enter new ones are growing.

- People are scrambling for leaders who can give them a sense of what reality is or should be, and we call these community builders. We call these content creators. But really, I think these are reality entrepreneurs.

- Fans are not just followers or consumers, but they’re investors in that leader’s model of reality. My friend calls this kaleidoscope theory, where culture fragments into thousands of shards. Each culture plays out its fantasies alongside all the other cultures, and the result is skyrocketing cultural innovation at the cost of shared alignment on anything.

- It’s a good trade-off, assuming it doesn’t lead to complete disaster.

Status Determines Incentives

- At a high level, status determines incentives. We as a society, if we give status to certain things and we do, we give prizes, we give awards, we give recognition, signal to other people that they should do it, because people are often searching for recognition.

- Recognition that the thing they’re doing is contributing.

- In a fashion sense, what you wear does indicate certain status. And there are all of these indirect signals of status.

- Status particularly matters for a person’s perceived skill level, experience, or ability to make things happen, because they want to be seen with people at a similar perception level, such that they are considered for the same opportunities that those people are.

- Status can be connected to a company’s brand in interesting ways too.

- James, I remember you had a quote on my podcast where you said something like, “Brand is the gift you give to people so they can easily explain to others why they’re working with you.”

Give Users Real Utility, Not Just Status

- There’s sometimes this trade-off between status and utility.

- If you’re optimizing for status, you want to be somewhat exclusive. Princeton, Harvard, Yale, they max out at 7,000. They could get bigger if they wanted to, but I don’t think alumni would be too excited about that because they personally want status.

- At the same time, if there are more people, there’s generally more utility.

- If you’re looking for a Co-Founder, if you’re looking for a hire, if you’re looking to fundraise, if you’re looking to sell to somebody, the more people who are in the community, the more utility there can be. It’s an interesting set of trade-offs.

- James, in your podcast with Eugene Wei, you talked a lot about the status utility and entertainment framework. It was a fascinating episode.

- I think what people often do, or what we think about, is really trying to thread the needle where you can get the status and utility elements.

- You start out these communities with high-status optimizations, you get the right people, you get peers, you get people who want to be with each other.

- The challenge, if you stop there, is that it reverses the network effects. Basically, the more people you get, the worse it becomes.

- You have to use status to bootstrap utility. You have to add enough value beyond the signal, such that people are willing to give up a little bit of the signal so they can get more utility in the process.

- That’s what I think YC has gone through, which has expanded class sizes from 20 people to 200 people.

- One of the things I think they say to their Founders is, “Hey, you’re going to have this network of 2,000 other Founders that you’re going to be able to hire from, raise money from, and the network is going to be so much more valuable.”

- I think that trade-off is something that communities should be very deliberate about. When to make that transition, how to optimize for it and not to make it too soon.

- As in, not optimizing for utility from day one, because you’re not going to get people through the door.

- The Thiel Fellowship is another example where they’ve optimized largely for status. I think they could have gone 10X bigger or they could have been 100X bigger. But I think that they’re fine for what they’re wanting to achieve.

- As a nonprofit philanthropic effort, they seem satisfied, but I think they could have really taken on Stanford or Harvard in a material way if they made that transition.

- Another interesting framework for how people think about these networks is, “Come for the tool, stay for the network,” which I think Chris Dixon coined.

- The alternate phrasing also works, which is, “Come for the network, stay for the data, network effects, or value that the network can create.”

- Stay on Quora because you know you’ve got all this data. Stay on Product Hunt because now you can get your startup in front of so many people. Or stay at On Deck because now you can connect with investors or hire all these people.

Many-to-Many Relationships

- A lot of these great communities first form with an audience, by writing, podcasting. or starting an interesting conversation in public to draw people in.

- You can then turn that attention from one-to-many to many-to-many. A lot of people don’t make that leap because they don’t see the benefits of going many-to-many, because they think they might lose some of that exclusive relationship.

- What people should realize is when you create the many-to-many, a lot of people credit you for making that connection.

- So, with a few people in a room, you might unlock 10 relationships. But if it’s many-to-many, there are hundreds or thousands of relationships, depending on the size of the room, that can form.

- Many of them will have you in mind as the genesis of their relationship and you develop a lot of social capital from that.

What Makes Great Communities: Value and Values

- I think what makes great communities comes down to this framework, value and values.

- Value is creating a place where people can get utility that helps them solve the core problems that they have.

- Values is the set of values that people can build their identity around. A common mission and common interests that people can bond over.

- I think value is more on the user acquisition side, values is more on the retention side. It’s a reason to gather initially and a reason to keep gathering.

- In terms of who can be good at it, you have to be a positive-sum-oriented person. You have to want other people to genuinely connect with each other and offer value to each other, even if you don’t get anything in return right away.

- You have to be a long-term thinker. You have to be a karmic person. You put good stuff into the world and it will come back to you. That’s a learned skill.

- And you have to be a strategic thinker. You have to understand what people really want. And honestly, not what they say they want, but what do they really want? And then you have to be crafty and clever about giving it to them.

Product Hunt’s Early Community

- I was the first employee at Product Hunt with Ryan (Hoover), the Founder. We very quickly hit product-market fit. But it was almost to our own detriment because we didn’t really understand the mechanics behind it.

- When we tried to scale or expand categories, we were basically doing new startups without realizing what the magic was.

- We really were solving this pain point around distribution for startups. They didn’t necessarily want to go through a journalist.

- I got this useful framework from this consulting firm, People & Company: you want to spark the fire, stoke the fire, and spread the fire.

- Spark the fire is: How do you get something off the ground?

- Spread the fire is: How do you create the rituals and infrastructure such that it can expand beyond you?

- And spread the fire is: How do you scale? How do you empower people in the community to become leaders such that it scales way beyond you?

- The biggest mistake people make when trying to spark the fire or trying to start the communities is just assuming it’ll happen.

- They just assume they will build it and people will come. What people don’t realize is that a lot of great communities, Product Hunt included, were very manual at the beginning.

- They’re simultaneously manual, but you also want it to seem as community-driven as possible. You don’t want to deceive people in any way, but you want to create precedents and templates that people can see, use, and imitate.

Early Communities Should Be Like Nightclubs

- The first thing you want to do in your community is similar to a nightclub. You want to get the people who, if you get them in the community, everyone else is going to want to come.

- And of course, just like nightclubs, it’s the very attractive people. At Product Hunt, this was the investors. If we had investors, we knew we’d have a lot of Founders. And we were also manually reaching out to investors and Founders to matchmake.

- As another example, anytime Josh Elman would tweet a product, we would post it on his behalf. Most of the products at the beginning were just us posting on other people’s behalf until other people saw that behavior and said, “Oh, I want to get credit for posting someone else’s product.”

- We also gave all the early users numbers so they’d say, “Oh, I want to be user 70 on Product Hunt before it hits scale.” It was really about getting the status dynamics right, but also making it as easy as possible for the right people to contribute early on.

- Early on at LinkedIn, Reid had his influential friends join. Even though it was a somewhat exclusive community, it really set the tone.

Build In Public

- When you build in public, you enable people to get involved and have a sense of ownership over the community. They have a sense of involvement.

- Every great community becomes part of your identity. If it becomes part of your identity, then you are invested in making it better. This is why universities and accelerators are so powerful.

- Once you’re in someone’s Twitter or LinkedIn bio, you’ve got them. They’re invested in spreading the good word because if they say good things about the community, they’re saying good things about themselves.

- We had that early on with Product Hunt Makers and community members.

- We would also build our roadmap in public. We put Invision designs up so that people could give us feedback.

- We had a Slack group for super active early users. If we were going to launch a new feature or think about a new category, we always got feedback on it.

- Building in public is a great way to get people included, such that it becomes part of their identity over time.

How do you make your early users look like stars?

- People are not naturally eager to try out your new thing, you have to incentivize them to do so.

- The key question is: How do you make your early users look like stars?

- We would give people usernames. It was like Twitter, everyone wanted their first name. There’s some status behind it.

- Think about how you can make your first 100 community members really look like stars. Maybe it’s special badges, special titles, special features on your newsletter.

- Most people, if they don’t have to do any work and you make them look like stars, they’re going to say yes. And that’s only going to help you establish your brand and credibility.

- Once you give them eyeballs and recognition, they’re more likely to share it to give you eyeballs and recognition. That was the trick behind Product Hunt.

- Product Hunt was not that complex. It was a forum where we gave people recognition in this daily competition. In exchange, they would give us eyeballs by sharing it, trying to get to the top. It was a little bit of a hack in that way.

- As for what’s next, I’m very excited about where crypto can go in terms of actually giving people financial ownership of the community with tokenization.

- But in the meantime, any status, special role, or unique value that you can give them to really be owners is very powerful.

Status Gives People Frictionless Approval

- We are wired to seek approval from others, because throughout history, if we were kicked out of the tribe, then it would have been very difficult for us.

- It’s against our nature to seek disapproval from our family members or our close friends.

- What status gives people is that frictionless approval, such that they can do this and it helps them in those ways.

- If you look at Y Combinator, for example, they probably do the most companies in venture, 400 companies a year. Benchmark will do just a few.

- But when Founders tell their mom or whoever, their close friends back in high school, they’ll say YC first, because they acknowledge that YC has a status that transcends the Silicon Valley community.

- The small group in Silicon Valley, they obviously know Benchmark is a different kind of signal, but externally, YC has a bigger status boost.

- This is similar to Stanford and Harvard and that just makes them really powerful.

Tribal Network Effects

- James Currier: We recently wrote an article about the 15th network effect, called tribal network effects. One of the things that we pointed out there is that the network members within a tribe are taught to be intentional about building the value of the tribe.

- They will do things like add value to other members and defend the tribe’s reputation. This is intentional value creation by the nodes of the network, which is really distinctive from other types of network effects where nodes largely contribute value and drive network effects unintentionally.

- You get on Facebook and you just do your thing, and you’re driving value to Mark Zuckerberg and his team without really intending to do that.

- But Harvard will fight the Yale guy when they’re drunk at a bar in Manhattan to defend their tribe, or at least that’s the picture we have from the 1930s. Do you find this playing out in the tribes that you’re building? Do you see ways of encouraging people to intentionally drive value into the network?

- Erik Torenberg: This connects to a big question which I’ve thought a lot about, which is how do you create the next Harvard or Princeton?

- You’re a passionate Princeton alum. How do you create an institution that engenders that type of loyalty? How do you create something like Y Combinator?

- It’s interesting because people don’t fully appreciate how strong these businesses are because they often don’t have tech moats in the same ways.

- But tech platforms get disrupted every few decades, whereas universities have lasted centuries. If you look at the top 10 universities, there are none within the last century.

- It’s for other reasons as well, but it’s also because these brands are just so durable and so strong.

How to Engender Loyalty

- I’ve thought of a couple ways to engender some of the same loyalty that universities benefit from.

- One way is that there are undue benefits if you put someone in business. If you are their first check, you’re the first person to believe in them. You’re the first person to bet on them in some financial or just social capital way, they’re going to remember you.

- I remember I was talking to a partner at Sequoia who said, “Hey, it’s interesting. Airbnb went through three months of YC, then we backed them, we sat on the board for 10 years, invested millions of dollars in the business, spent way more time than YC ever did, and yet every time they go out and speak they mention YC first.”

- A lot of it is just the arbitrage of putting people in business. If you do that, if you help people at a critical inflection point that they’re going to look back at and remember fondly, I think you have the moral authority to ask them to do the same for other people. You can say, “Hey, we paid it forward for you. Do it for someone else.”

- And they’ll do it for someone else. That’s something that I think people miss out on.

- The other thing I’ll say is the importance of legibility. It just goes back to brand and status, just having a very clear process and clear way for how you do business.

- I think some of these venture firms, they’re not as legible as something like YC.

- We’re building an accelerator as well at Village Global, which has a very consistent cadence to it. There are applications, it is three months, it has an orientation, it has a graduation, they even have a prom. You go through a similar experience.

- Now, anyone who goes through that experience five years later, you can connect with in a very deep way. It’s that shared set of languages and rituals that everyone goes through and that helps build community and tribal belonging.

Three Hacks for “Sparking the Fire”

- Universities are a four-year onboarding to a community for the rest of your life. I’m sure you’ve connected with alums decades apart and you’ve shared that common experience.

- I think it does beg the question, how do you start? How do you get things off the ground? How do you spark the fire for something like a Princeton?

- I think there are three ways, three hacks that I’ve figured out.

- One is you align with already established brands. So at Village Global, what we tried to do was really partner with these luminaries as LPs that would bring us, if anything, just some attention and a brand day one in a very crowded market.

- It’s also important to align with preexisting brands and try to borrow their social capital.

- The other way is truly just having a differentiated utility, such that people aren’t coming for the status, they’re coming for the value on day one.

Citizens of the Internet

- On Deck, for example, is a company I started to serve this community that was underserved, which was, “Hey, I’m an engineer at Airbnb or Facebook, or whatever company. I know I want to start something. How do I meet all the other people like me?”

- At On Deck, we say, if Stanford is trying to teach you to be a citizen of democracy and society, we’re trying to teach people how to be citizens of the internet.

- So what might you want to do on the internet? You might want to start a business, build an investment portfolio, build an audience, start a newsletter, write a podcast, level up in your career.

- On Deck is trying to be Stanford if it was digitally native, starting during Covid in 2020.

- We’re first starting with the Stanford MBA for Founders solely focused on programs that help Founders.

- This is the big lesson from the product, which is that if you’re going to scale and expand categories, you need them to either benefit the core directly, make it stronger, or benefit from the core. Otherwise, you’re just doing new startups.

- At On Deck, we’ve had all these different opportunities to do things that don’t relate to Founders and we’ve said “no.”

- It needs to help Founders either raise money, hire people, or get distribution. Maybe later we’ll go outside of that but that’s where we’re focused right now.

- The two broad goals I’m hoping for, or aiming to do with On Deck and Village Global is to incentivize more Founders and more investors to raise the status of pursuing the startup path.

- James, I know you’ve talked a lot about people who spend five years at Google or whatever big company it is, they should have some incentive to try to build, to really contribute and innovate. That’s what we’re trying to do.

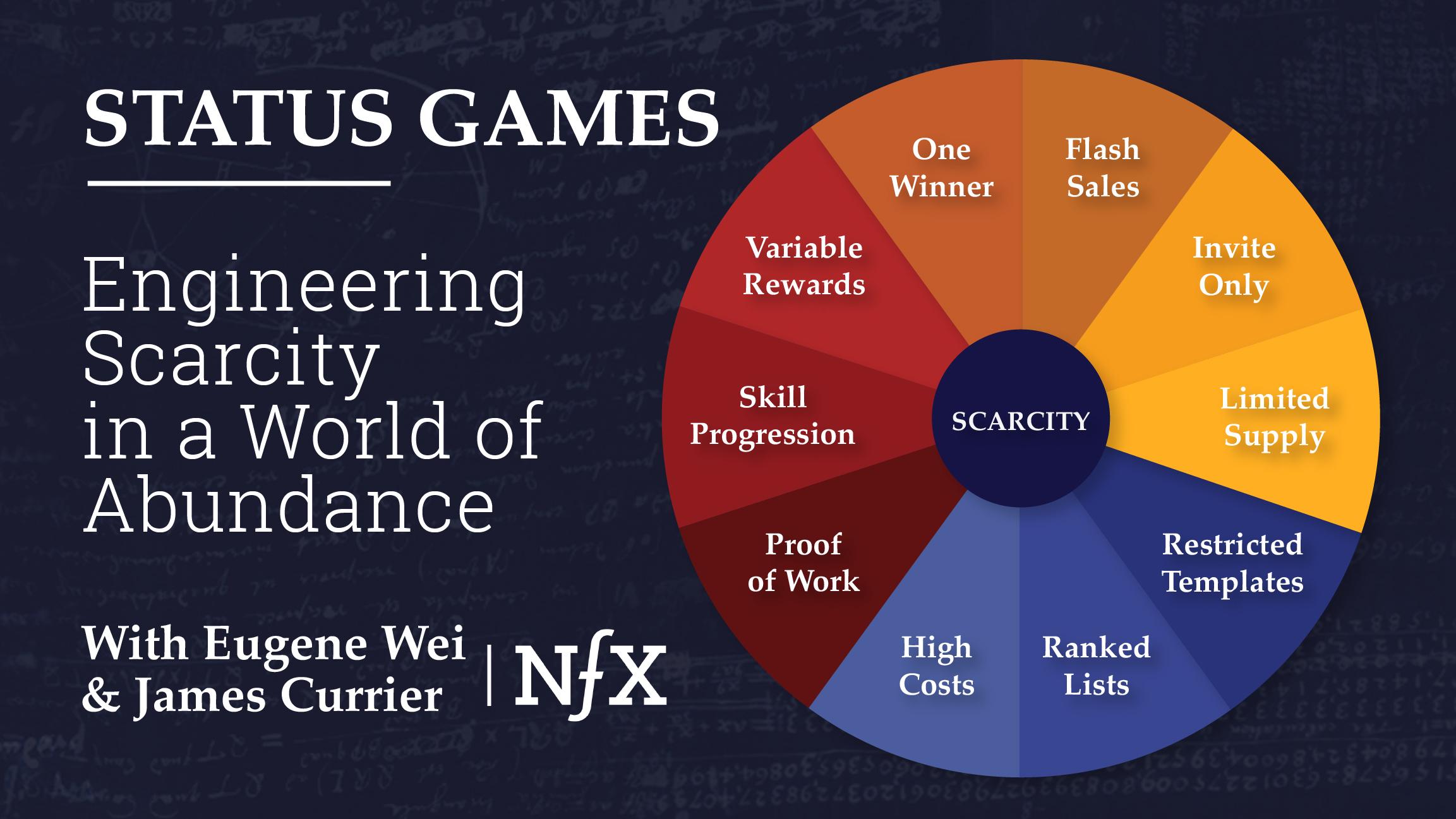

Product Is No Longer What’s Scarce

- Community is really helpful in an era where the scarcity is not the ability to build the product, it’s the distribution and user attention. If your community is your product, then you a hundred percent need to think about building community.

- And it’s only getting easier to monetize as a content creator and as a community builder.

- If community is your product, you should aspire to be in their Twitter or LinkedIn bio. You should be part of their identity in a real fundamental way. And you’re not really core enough until you get there.

- If it’s a marketing tool for a separate product, community is a great distribution platform, but you really just need to focus on utility. You don’t need to become part of someone’s core identity, but you should be investing in value and in values.

- It’s going to have a long-term benefit. You might not see it from day one, but if you plant the seeds and you do it well, it will grow into a real advantage for you.

“Expanding the Circle of Empathy”

- There’s this great Bedouin saying, “Me against my brother, me and my brother against my cousin, and then me and my brother and my cousin against the neighboring family.” One thing it’s meant to signify is that people often bond over common enemies. That’s just who we are.

- What I’m interested in doing is expanding the circle of empathy, making the common enemy as abstract as possible.

- I was hoping it would be Covid, maybe it’s aliens. We’ll see.

- Tribes can be the cause of conflict, but they are also the cause of meaning, of friendship, and of loyalty. I think we should have more nuance around the acceptance of the word tribe and the connotations of it.

- But we should also try to expand the circle, such that the enemy has some abstraction or instead, it’s some goal like economic growth or something that you are striving for because we need transcendence as people.

- We need a goal. We need something that we can commonly aspire to and you want to make that as positive as possible.

You can listen to the entire podcast conversation here.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.