Finding defensible magic is hard. Completing your Ph.D. is hard. Building a company is hard.

Understanding how VC works should be easy.

But so many scientist-founders never get the full breakdown. Once you see how it all fits together, everything makes sense. Why some companies get funded and others don’t.

This is the stuff that I learned over the years as a founder and investor. It’s the stuff that people say, and the stuff they don’t say but expect you to know anyway. (The latter is far more important).

I made 148 different versions of my pitch deck for my company when I was a scientist-founder. In hindsight, as an investor, they all look stupid. What I was missing was an understanding of how investors think, and what incentivizes them.

So I want to share this with you so you don’t make the same mistakes.

Hopefully, this is the last primer on VC you will ever need to read.

ACT I: The Investors

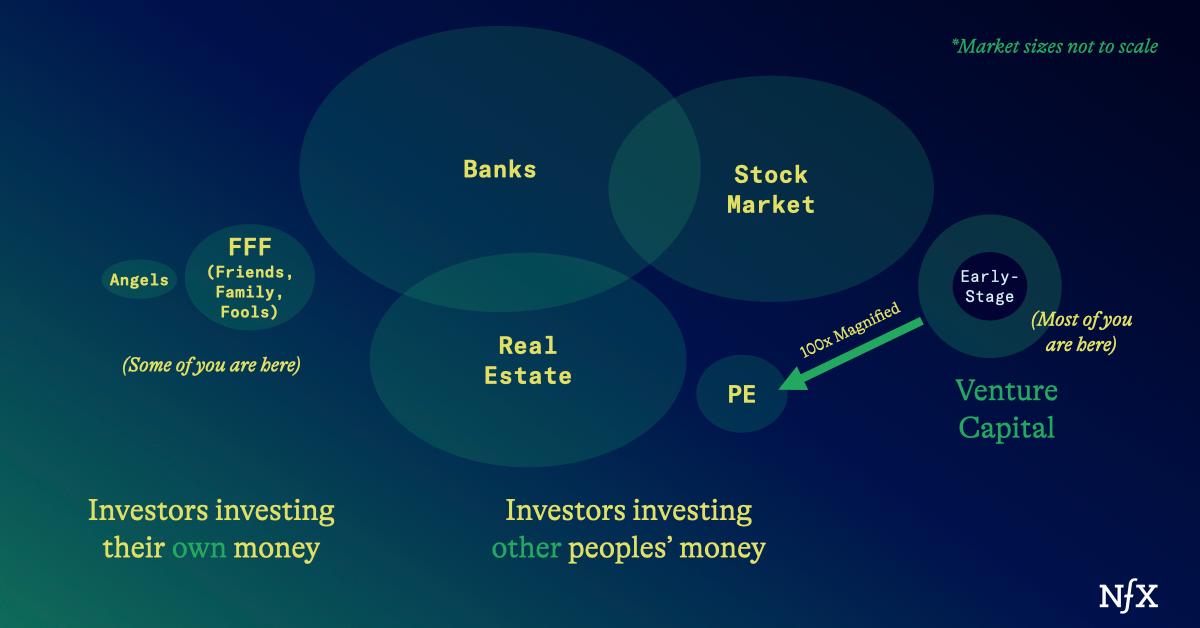

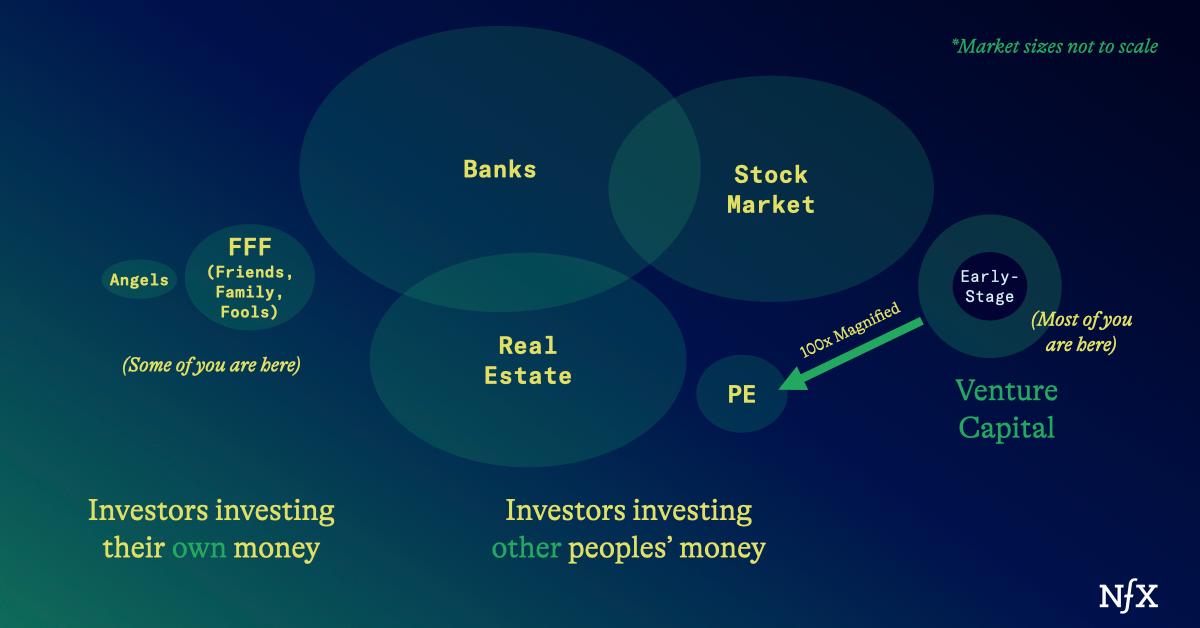

There are two kinds of investors. People who invest their own money. And people who invest other people’s money.

People who invest their money are called angels. They have no real rules. Everyone is motivated by making money, but they might also invest because they like you, or feel connected to your idea. Usually, they can’t or won’t invest the amount of money you’ll need over your company’s whole lifetime.

This is why we need to focus on the other types of investors: people who invest other people’s money. This is a broad category that contains things like real estate investing, hedge funds, banks, etc…

In that category there are investors who put money into startups – also known as Venture Capitalists. While they are probably the most well known in this category to founders, dollar-wise, they are small fish in an ocean. Most of the money out there is in real estate, in cash accounts or in the stock market. An even smaller portion is allocated to private equity investors, and an even smaller portion of that to early stage VC.

And there are certain rules they have to play by.

A rule in life: you always get what you incentivize. So you should understand the incentive structure behind venture capital. It took me a while to understand this too, at first.

The most obvious well-known incentive is the 2%/20% structure.

For every fund raised by a VC, the partnership usually get ~2% a year in management fees to pay salaries, run the events, travel, etc. Once you return the fund, you start sharing the profits 20%/80% with your LPs (limited partners, the investors in the fund). That’s the upside of having a successful fund.

For some funds, it can be higher or lower than 2%/20% but this is the general rule of thumb.

The second fact you need to consider is that fund lifetimes are between 10-15 years. For LPs to put money in your fund, they need to lock up their money in this non-liquid format for over a decade. They need to get a premium for putting it in a fund instead of a very liquid vehicle like the S&P500.

VCs are expected to return 3x a fund about every ten years. Most of them can’t even achieve that. And more is obviously better.

The third rule: This is the rule all humans play by. We want status. We want to be loved, respected, admired. And in VC, you do that by investing in the biggest, most successful companies. These companies are attached to their names forever. You get to the midas list by investing in the likes of Amazon, Moderna, Google, or SpaceX.

So your VC has ~10 years ticking clock, they have a certain amount of upside to gain, and if they want to keep in business (and gain the admiration of peers) they have to make the right investment decision that will return the fund, plus.

Often it really is just one big decision. Which tells us a lot about VC psychology.

ACT II: What Does This Tell You About How VCs Make Decisions?

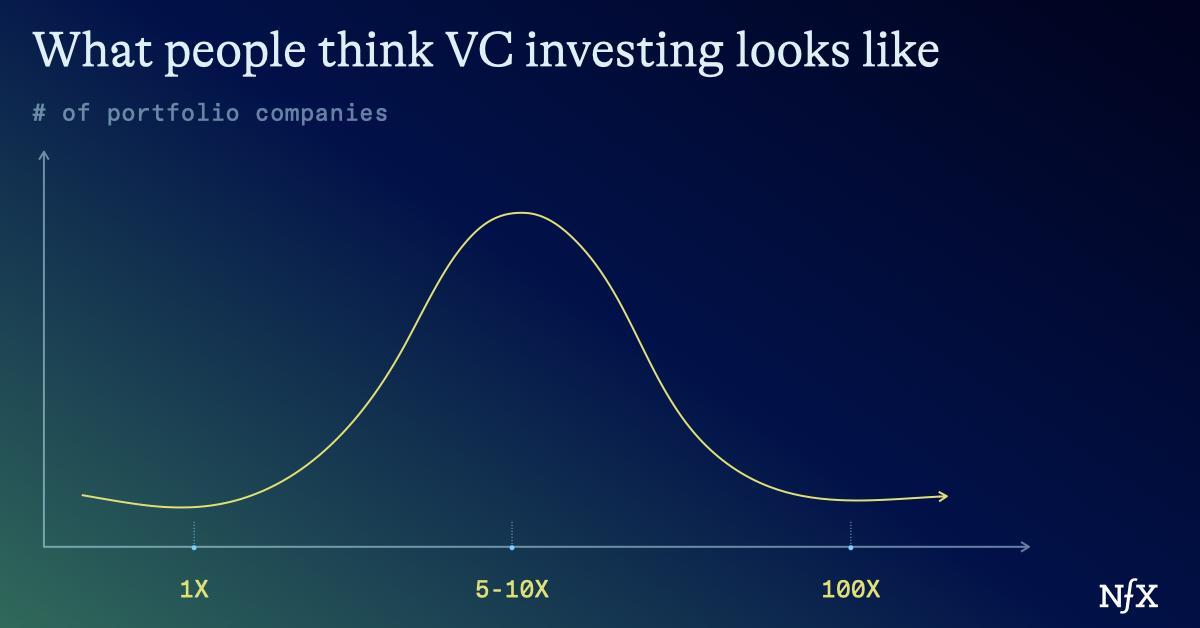

Most people think that VC life is easy. They invest in companies, they wait, and then some of those companies get acquired or become a liquid public market stock via IPO. And those returns fall into a nice bell curve. Some companies are doing great, most doing okay, some doing little to nothing.

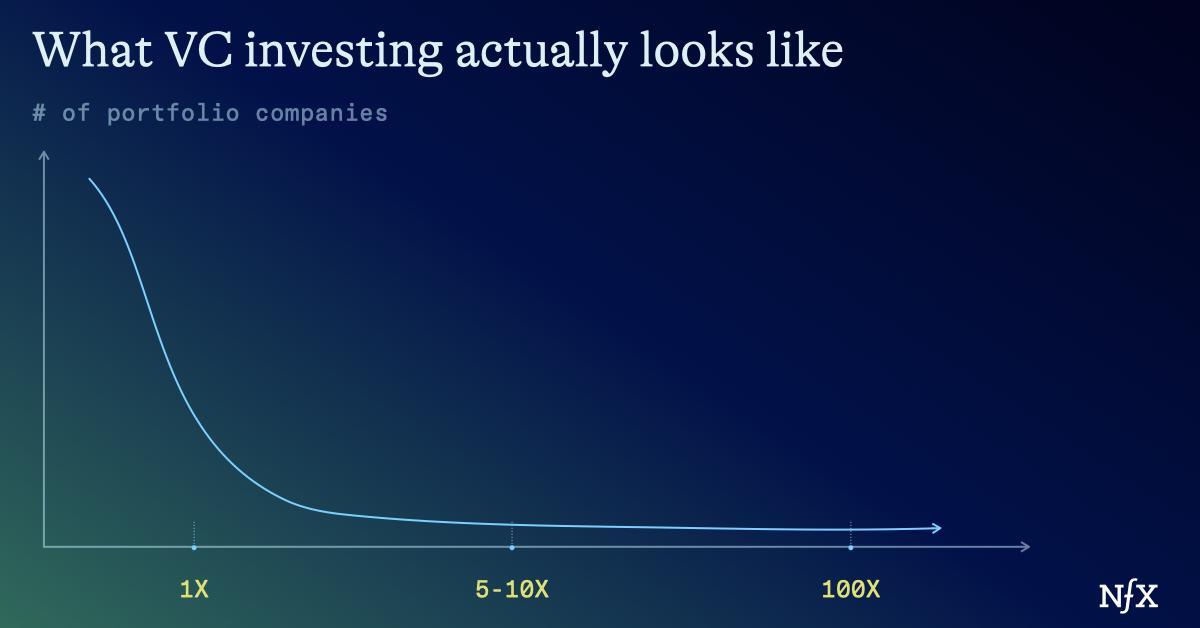

It’s not like that at all. It actually looks more like the harshest power law you’ve ever seen:

For seed investors, most companies will probably return 0 to 1x. A few will make a huge return, and those that do go that way usually do even better than most investors expect.

Because of the power law, every investment you make has to have the potential to return the fund. As an example, If I have a $100 million fund, and I own 10 percent when a company gets acquired or IPO, I need that company to be >$1B just to return the fund. That’s why chasing unicorns and decacorns (multi-billion dollar companies) is so important.

It’s like the movie industry. Most movies will flop. We need to make giant blockbusters.

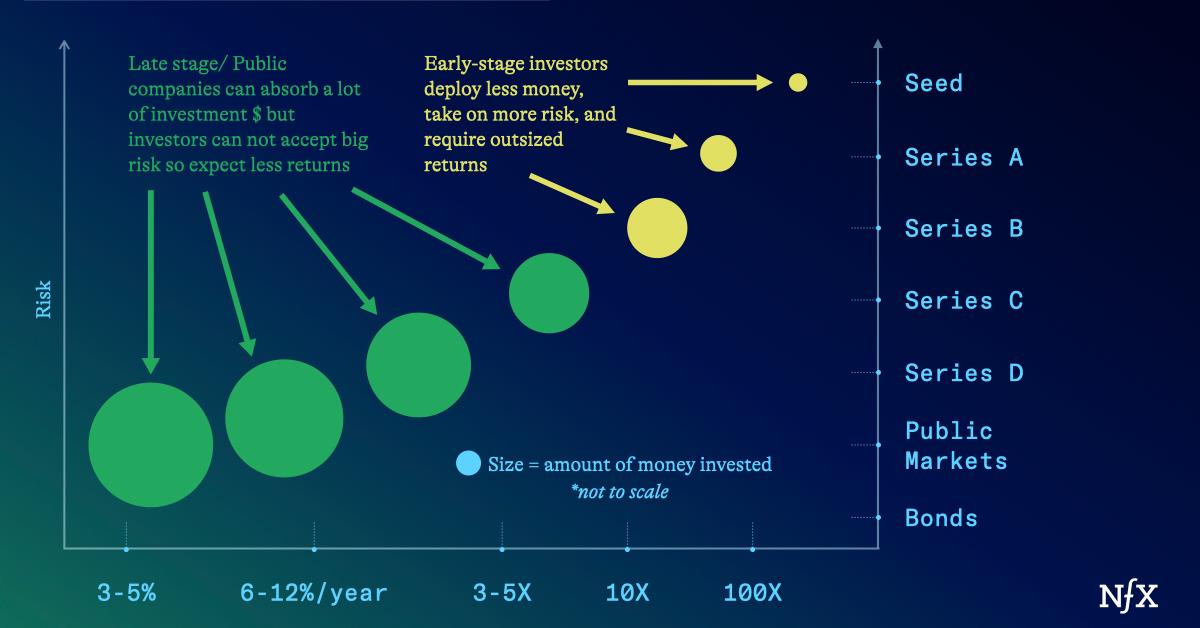

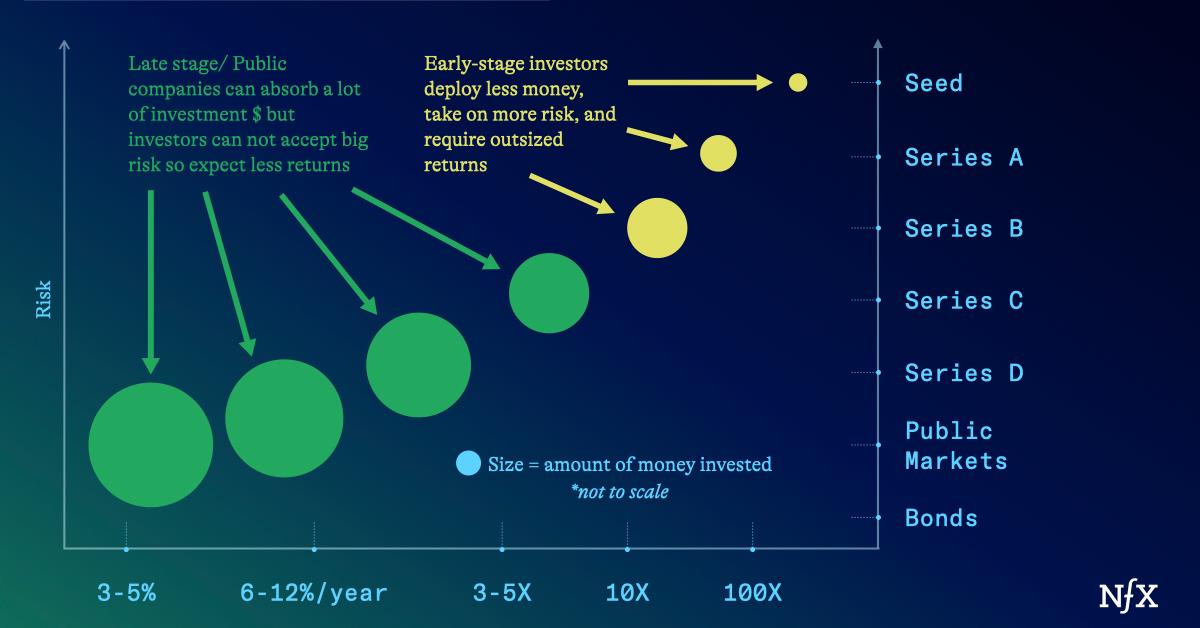

It’s also important to note that this risk/reward paradigm actually changes depending on the stage you tend to invest in.

The earlier you invest, the less money you can deploy. Usually seed checks are a few million, later stage checks could be hundreds of millions, while public markets can absorb billions.

The earlier you invest, the more risk you are also willing to take. While no one is expecting to lose all their principal in a cash account, even the best early stage investors expect to lose money on more than 50% of their deals.

Because of this dynamic, at an early stage, every company has to have the potential to return the fund.

So, let me take you inside the investment meeting. In the meeting, the partners will present the companies. In everyone’s mind, is one question: can this company return the fund?

At NFX, we break it down into three things:

- Can this be big enough?

- Do you have defensible, differentiated magic?

- Are you the right people?

*We are going to go into these in depth below.

Why So Many Founders Struggle With Fundraising

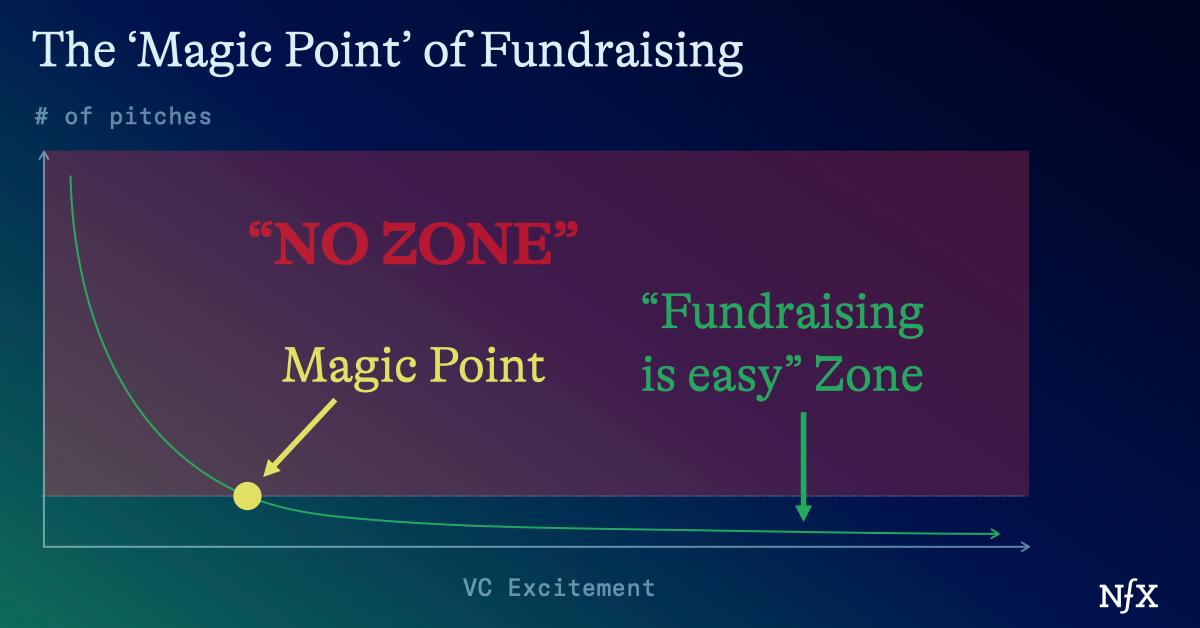

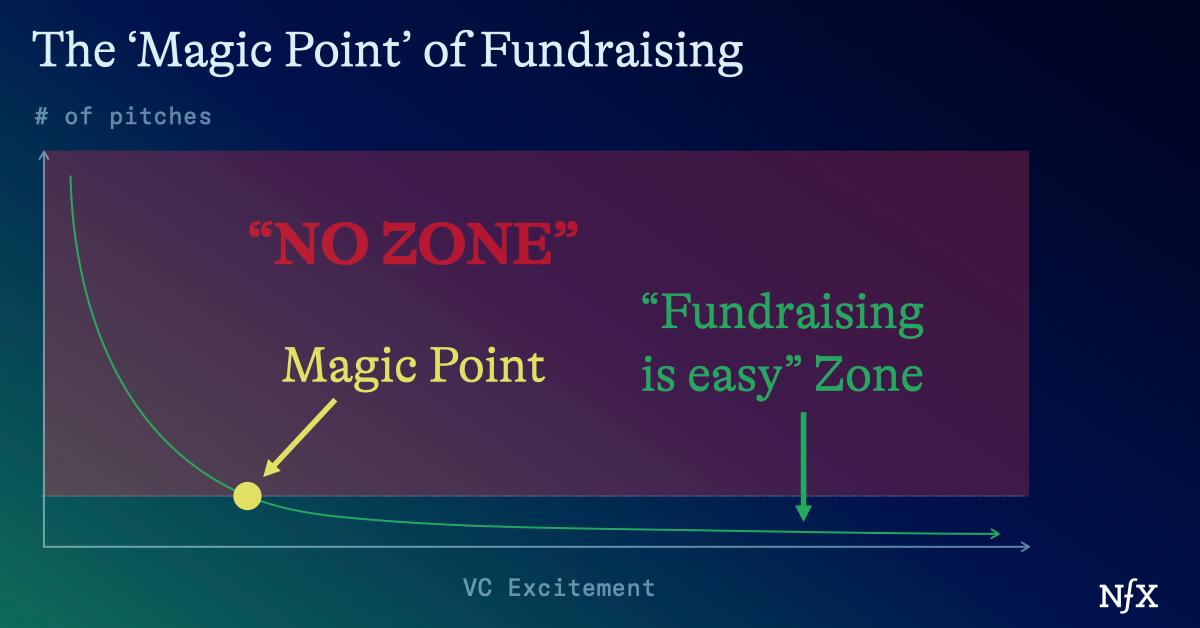

Some founders find fundraising very hard. But for some, it’s easy. Why?

That’s because you reach “the point” where your signal rises above the noise. You leave the “no zone” and enter “the fundraising is easy” zone.

Why does that happen?

Because your story is convincingly big enough. Then everyone believes you are the “hit” they need to return the fund.

Below we will discuss how to rise above the noise. Remember, it is all about the three things: Big enough, defensible magic, and the right people.

Rising Above the Noise Part I: Big Enough?

Remember: You must be capable of being huge to even be on the radar of an early stage fund. Some things just aren’t big enough for early stage VCs. You could be the best restaurant in Palo Alto with the best chefs in the world, and you probably won’t generate enough to return our fund.

You can examine how big you are by using this formula

To A x B x C >=$100 million in revenues or >$1B in market cap at 10 times earnings

A= what you are selling

B= how much it costs

C= gross margins

As a VC we need to believe that at a bare minimum you can reach this, and potentially go much higher.

Don’t worry if it will take time to get there. We account for that.

The thing that most people don’t get about early stage investors is that we actually lose the most money if we don’t invest. It’s okay to lose our investments in most companies, it’s not okay to miss investing in the next Google.

We have to be optimistic. Even though we say no most of the time, even though most companies will fail. Because the best companies actually end up doing even better than we think they will.

This is why big is important. If we make a bet and win, that win has to be worth it.

Rising Above the Noise Part II: Defensible, Differentiated Magic

Once you realize your idea is big enough, you need to focus on becoming something truly special.

Competition is for losers, as Peter Thiel has said. So the first thing you need is defensibility.

In bio that can be IP. In software companies, that might be network effects (NFX 🙂). Anyone can copy facebook, but not anyone can get billions of users.

Second: you need differentiation.

Many business models are based around trying to get someone to care about a certain thing. But people don’t care about most things. People only care about their own stuff. Why would we care about just another product or service in a sea of things?

For every idea you think is unique, we have heard several pitches. So to be novel, to rise above the noise, that idea has to feel magical. Imagine things like rejuvenating human cells, genetically modified glowing plants, curing cancer, or building a mars colony. The amazing thing about bio is that nature has created so many magical things, and if you have discovered something like that you just know it. It would be a shame to waste something so magical.

Today, we all know CRISPR was a breakthrough technology. But think of all the students at Berkeley who had heard about it back in 2010, and just moved on with life.

The truly huge companies are n of 1, and that is because they are built around things that look and feel truly magical and can build defensibility moats around their business.

Rising Above the Noise Part III: The 100th Percentile Team

Finally, You have to have the best team in the space. And this is the thing that many VCs won’t tell you to your face.

If you aren’t getting feedback on why you didn’t get funded, it probably is because you were not the highest quality team the VC saw in that space with a similar idea.

It makes sense. It is the hardest feedback you can give to a person. It’s not that you are incompetent. It is that you can be a 95th percentile person, and still that isn’t enough. You have to be a top percentile person. We mean super unique, super people.

There’s a reason Sam Altman could raise money to start a new company tomorrow if he wanted to.

It doesn’t mean you should give up if you are an unknown scientist-founder. We are looking for a founder-market fit. If you are the top person in the world working with your technology/the inventor of your technology, you are the right person. Just find other top people who know things you don’t.

Founder Takeaways

Now that you see the whole picture, keep this in mind.

You will not be perfect. But don’t try to be perfect. We look for signs of excellence, not lack of weakness. There are different combinations of these components that create the correct mixture early stage investors need to fund you.

For example: If you have all of these things but are a B+ team, it’s not enough.

If you are a super person, with a history of success, odds are you don’t even need either of the other elements. If Elon Musk started a company tomorrow, even with a mediocre idea, would you invest? Most would.

The best thing you can do right now is take an honest appraisal of those three elements. Understand where you are weak, but focus on where you are excellent.

And then, tell your story correctly.

Don’t waste time building it up.

Show us how big you can be right away.

Whatever your excellence is, make it clear.

This is particularly important for scientist founders: don’t be so in love with how cool your science is that you forget to tell the bigger story. If the opportunity is massive, most investors won’t care about the science (we will!)

If you are in a university right now, go discover something magical at the end of human knowledge.

And then tell us about it.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.