Many marketplaces superimpose some form of improvement on an existing market. They help people who are doing transactions already, do them more efficiently. But if you want to create a truly iconic marketplace, you can’t just have a theory of “better” — you need to have a theory of change.

This requires disruptive marketplaces — like Airbnb, Outdoorsy, Uber, Doordash, Poshmark, Outschool and more — which enable participation among non-participants by creating new types of transactions altogether.

To uncover frameworks for disruptive power in your marketplace, I connected with my friend Scott Kominers who, together with Tom Eisenmann, co-launched the “Making Markets” course at HBS. When I look at the landscape of people who are thinking deeply about how digital marketplaces work, Scott is the guy.

Below are highlights from our recent conversation on the NFX podcast. Let’s dive in.

The academic field of market design has historically been mostly focused on questions of public policy market design. But for years, Tom Eisenmann (Harvard Business School entrepreneurship professor) and I were thinking how we could take market design and teach it to founders and MBAs — because many startups actually have marketplace dynamics embedded in them, even if they don’t always think of them as a marketplace.

Our first challenge was in trying to understand the real practical problems that marketplace founders face, and then trying to organize those into frameworks for startup opportunities.

In building these frameworks, Tom and I took a first principles approach to guide us:

- What are markets for?

- Why do they create value for people, for society?

- And then in what ways can markets break? If people really want to transact, how is it possible that they might not?

The third point is where we can do a deep dive for marketplace Founders. Examining the transaction types helps us understand how to design your marketplace for your participants (and critically, for the non-participants).

When Marketplaces Improve Existing Transactions

Many marketplaces superimpose some form of infrastructure on an existing market. They help people who are doing transactions already, do them more efficiently — giving them more assurance, or reducing friction, or increasing transparency, or increasing insurance, or digitizing it, a.k.a. make it doable from your smartphone. These marketplaces improve existing transactions.

My Ph.D. advisor, Al Roth used to say, “A market where you see rules that should never have to be rules has some problems in it.” I’m going to generalize that to: Look for a market where people are trying very hard to transact, going far out of their way to participate in a transaction that’s really, really difficult to do. This indicates real potential value.

If you see people doing that, there’s something there. If there’s so much friction that it’s unimaginable that anyone would do it in the first place — and they’re doing it anyway? That suggests there’s a real reason to help them do it more easily.

I tend to think of Angie’s List (now Angi) in this category. Their market cap is around $5.6 Billion. They’re enabling a much more efficient market for home services. That’s really good because it’s really hard to navigate home services contracting. It’s super hard to find somebody to repair some part of your house, who is going to do a good job and be trustworthy and so forth.

Creating a system for managing that market is really, really valuable because a lot of people waste a lot of time on it, on both sides. If you’re a provider, you spend a lot of time trying to find customers and figuring out how to credential yourself. And if you’re a customer, you spend a lot of time trying to find a provider who’s got the right skills and the right abilities and who you can trust to do the job well.

So mostly Angi wins by enabling this very frictional, highly inefficient market to move much more effectively. But they’re not enabling new participation. They’re not somehow bringing unlocking new contractors or home services that didn’t exist before.

Disruptive Marketplaces Create New Transactions

Here’s what “existing transactions” marketplaces don’t do: They don’t bring in new consumers who would never have been able to participate in these transactions before, or new producers who couldn’t have done this before. This requires disruptive marketplaces, which expand market participation by creating new types of transactions altogether.

It’s about enabling participation among non-participants. If these people weren’t participating in the old transactions, for whatever reason, those transactions must not have been right for them.

How Is There Value In Non-Participants?

Think about food delivery marketplaces. It’s really like in the Angi category. It’s not in principle a disruptive innovation because food is a luxury service. Having restaurant food delivered to you at a specific moment in time is a luxury on top of a luxury. Then at least on the consumer side, it’s an incredible luxury format business, at least in the abstract.

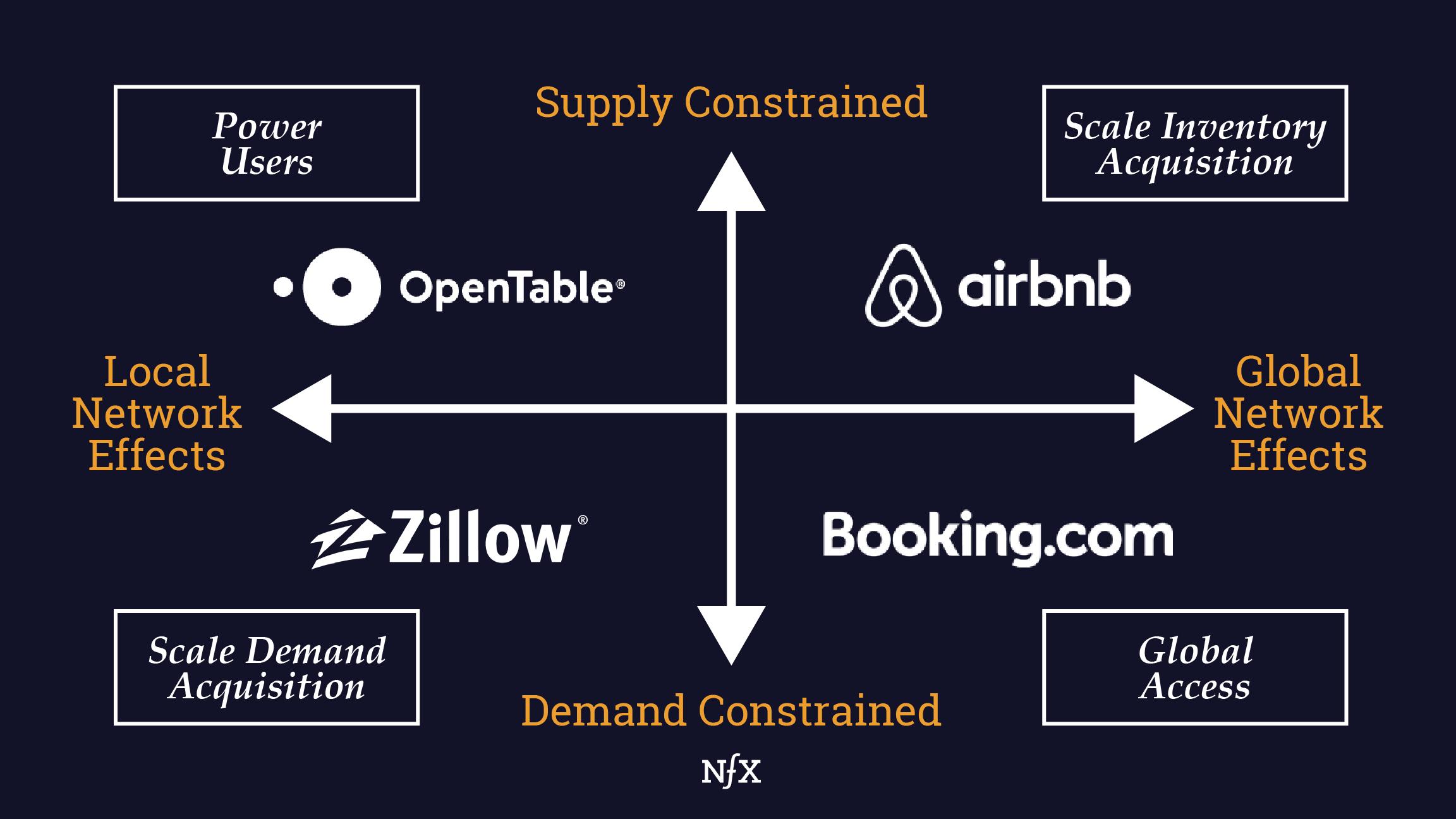

If you were operating that business, and you know it’s a luxury, your goal is to take the consumers who are already doing the most of it and help them do it better and more cheaply for you. You’re trying to create efficiencies in the market so it’s less expensive to provide delivery services and give those power consumers the opportunity to consume more, make it easier, make it better for them so that they engage in this luxury more and more often. If your goal is to grow a marketplace by reducing friction, you want to focus on these power users, the higher frequency users.

But if your goal is to be more disruptive, then you really want to think about enabling non-participants to participate. But in a marketplace, you have to be smart about which non-participants you want.

In practice, the way many of these delivery marketplaces launched was focusing on the wrong non-participants. They tried super hard to convince everybody to buy delivery food. They threw voucher after voucher, discount after discount, trying to get people hooked on the idea of buying this luxury product who were not previously consuming. And maybe they were willing to consume at the price point of the discount, but once the price went back up, they could only afford to buy delivery food as much as they can afford to buy it. However bad your sushi habit is, the costs add up and you notice.

These companies had this view going in, that their real goal was to get the people who were not big delivery customers to become big delivery customers. This led to launch strategies where they burned tons of capital and tried to recruit those customers, even though they turned out to not be recurrent.

Meanwhile, on the other side, that capital’s got to come from somewhere. They tried to make the money off of the supply side, charging the restaurants very high fees. But if you think about it, the restaurants were the potential non-participants that you want to go after, not gauge. Lots of restaurants had no delivery at all because it was too expensive for them to run their own delivery infrastructure. If you give them a net — a web of existing drivers, delivery technology infrastructure they can use and invest in making that a core part of their business — then suddenly you’ve brought all of the supply online that didn’t exist before. And your value to those customers is even higher.

And so the disruptive potential in food delivery was really on the supply side. Companies that started by trying to disrupt the demand side stymied their ability to really take advantage of the disruptive potential on supply.

You really should be attentive to: Who are your non-participants, really?

4-Part Framework For Unlocking Disruptive Potential

There are 4 transaction types that can unlock disruptive potential.

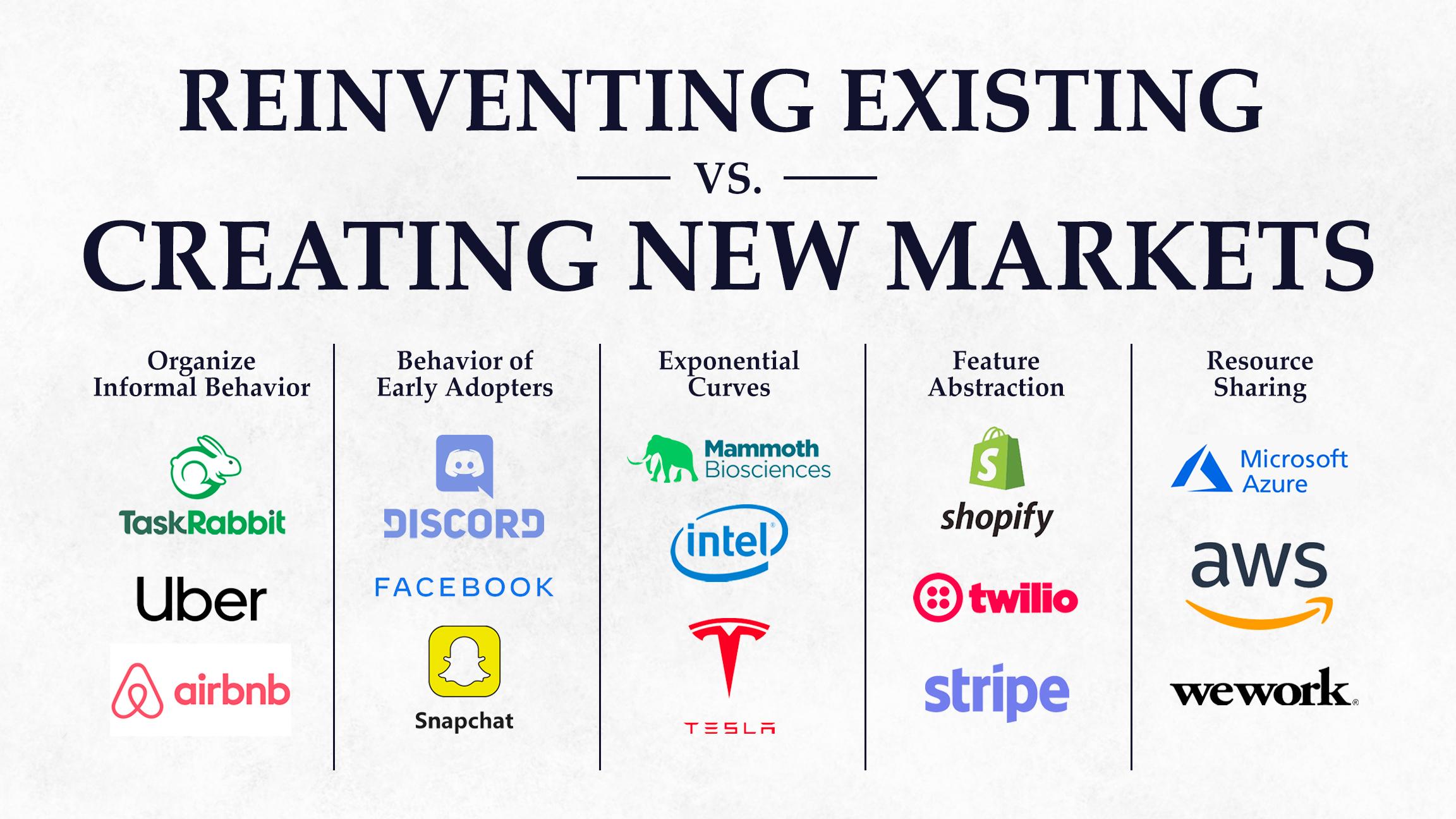

1. Smaller supply unit

Maybe the easiest one to think about is what we call a smaller supply unit or smaller unit transaction. Take Airbnb for example.

It created a new type of transaction on the supply side for people who were previously not participating in the existing market for travel housing, which was largely hotels. Their thinking being: “I’m a random person in the city, I’ve got an extra room in my apartment. I’m going to give you a towel. There won’t be a concierge, there won’t be housekeeping or whatever, and also the space is shared — instead of renting an entire room all to yourself in a hotel with all the services. This is going to be minimal.”

All of these things weren’t what a hotel user on the demand side was looking for, but there were still a lot of people who, for whatever reason, couldn’t afford to stay in hotels, or didn’t like the style of them, whatever the case, and Airbnb was exactly what they wanted.

It’s a unit that is smaller than what a hotel could provide. People were looking for travel housing, but a lot of people couldn’t get it because the existing option was too big of a unit for them to buy.

It’s carving things that were previously non-performing assets — extra rooms in people’s apartments and houses — and turning them into rental assets, to participate in the same type of transaction that people had been doing for years, but in a completely new way.

As an important side note: Airbnb differentiated the “hotel” experience in a way that in and of itself was appealing, and that suddenly allowed them to start sucking in.

What I mean by sucking in: In disruptive innovation, the disruption actually happens when the product becomes so good that the rest of the market now wants it too.

That’s when something that starts out being a play for the current non-participants, that’s not good enough for the existing participants, suddenly gets good enough that the existing participants want it also. That’s the moment I think of where it takes off, where now this is a substitute for a hotel. As disruptive innovations move up market, they often start displacing the original environment.

2. New Supply Opportunities

Another one of the 4 ways marketplaces can create new transactions is by making it easy for new suppliers to enter the market. Amazon Marketplace did that by making it easy for non-technical people to operate their own online stores. Substack and Patreon made it easy for creatives to monetize their skills, which unlocked a talent pool, a new supply opportunity.

In the Airbnb example, they started by creating something that an absolutely basic non-consumer could use, then very quickly moved up market to this much bigger, disruptive opportunity, which was bringing on the supply that’s easier to provide and smaller than a hotel and still with less overall infrastructure. People who would never have opened their houses before became Airbnb hosts.

3. Bundles

Then there are bundles: when you take a bunch of units from different suppliers or different units of demand and roll them into a bundle that is worth enough to sell. Think about something like ClassPass. You have all these gyms with extra seats and courses, but their business model is built around selling bigger subscriptions and memberships. It’s not worth it to them to sell the individual units because they risk cannibalizing their own total demand, their main business of memberships. ClassPass takes all those units and rolls them into a bundle across the businesses and sells that separately in a way that is non-cannibalizing. It’s targeting customers who don’t actually have demand for the main gym product.

A different example of bundles is Hotwire. They would take the extra seats on airplanes and say, “You can buy it on our website, but you don’t know which airline it’s on.” Which allowed those airlines to sell the extra seats without cannibalizing their main business on Expedia or through their own websites.

You have to provide a bundled unit in some form that’s not good enough to directly cannibalize the main market, at least at the outset, but that is valuable enough money for the operators that they’re actually willing to join the bundling platform.

4. Trust Wrappers

Our 4th category is trust wrappers. It plays in with new supply or demand a lot. The idea here is when there’s a sheer failure of trust for whatever reason, like you don’t know who your counterparty is, or you’re worried about the privacy of the transaction, or people learning information about you through the transaction or something. Certain transactions are highly constrained because a trust barrier prevents demand from engaging with supply.

So trust wrappers, then, create a certification or a safe harbor that makes it possible to transact with people in a way that has new forms of trust. Blockchains do this a lot by enabling you to transact securely with a party you don’t necessarily know or trust — facilitating transactions among parties who would otherwise be unable to access the market.

How Does This Framework Help You Spot Marketplace Opportunities?

First of all, it draws attention to this idea of non-participants, and it pushes you to get a sense in your head of whether you’re building a marketplace for existing participants or non-participants, because these are really different.

As a Founder in the marketplace environment, you’re envisioning a fundamentally different change in behavior. That often means the normal way of testing things, like what we do to find product market fit, are a lot harder, especially really early on. We often will see that Founders will be working on a marketplace for four years before anything starts to happen and those changes start to take place. You really start to see lift off in these marketplaces in years seven and eight.

You need a theory of change. You have to sort of have a model in your head of how what you do is going to change the way the market works.

When I try to understand a marketplace opportunity for Founders, I look for places where there is a principal source of value loss in the market — then I look to see that you have some special advantage in fixing it.

What is it in the market that’s stopping transactions from happening? Is it that people don’t trust each other? Is it that they don’t have a way to communicate? Is it that the search cost to find a good transaction partner is too high?

The specific design intervention you choose has to address whatever is actually driving the lack of value, or the loss of value.

You can be the world’s best executive. You can be the world’s best at recruiting suppliers, because you built a platform that’s super easy for them to use, it’s a really nice SaaS product, and every single one of them wants to sign on. But if the problem is that demand-side search costs are too high or something, or the demand side trust is low, or there’s something keeping the demand side away, then bringing in all the suppliers in the world doesn’t help.

I think of marketplace design as having 3 principal dimensions: curation, matching, and support.

1. Curation is structuring the transactions that can happen in your market.

A curation intervention might be vetting all the suppliers on your platform. And a result of that is that if someone knows, if they show up on the demand side, all of the suppliers have been vetted because you have done that, and so they can expect high quality.

Curation generally raises the average transaction quality and also the worst case scenario, in some sense. It makes the absolute transaction quality higher.

2. Matching is helping determine which ones actually do happen.

Matching is like helping people decide who to transact with or under which terms they should transact, so that could be, “There are tons of suppliers. We’re going to recommend five.” It doesn’t have to be saying, you’re going to transact with this one person, but it’s cutting down the search costs and all the complexity of figuring out who a potential partner could be.

3. Support is helping them to happen.

And then supporting services, these are things like payment processing, standard contracts, communications tools, and also things like value added services, like insurance or returns. If support makes the transaction happen more effectively, you as the marketplace organizer could have particular skill and advantage in any one of these dimensions. And that might also guide how you try and fix a market failure.

So, pulling all these together. You could try to improve average transaction quality. If you’re really, really good at vetting suppliers, you just happened to know the entire market. You know what makes a good supplier and you have a really efficient way of figuring out who’s high quality, then maybe you go for curation. You try to build a super narrow, heavily curated platform with only the best supply. And then your advantage to demand is that they know every transaction is super high quality.

If that’s really hard, then maybe you instead go for a support strategy, where you get really good at providing trust guarantees and insuring against downside risk, or you take on these, and you’re sort of insuring against downside risk; or you take on a lot of the transaction yourself, right? Like you, instead of having the supplier transact directly, maybe you sort of fully partition the market; you buy from the supplier, improve anything, any goods that are of lower quality, and then sell them directly to the customer.

But whatever the case, you might have different abilities and a comparative advantage in these different dimensions of the transactions, and that also guides what you actually work on.

Marketplaces, Rephrased As A Question Of Human Behavior

It’s very natural with marketplaces that they’re very hard to fly because even relative to other forms of entrepreneurship, you’re envisioning a fundamentally different change in the way people behave. All entrepreneurship changes the world but marketplace entrepreneurship isn’t just exposing people to a new product or giving them a new thing that they have an intuition for and want to use. They’re already doing something. There’s a failure to do something that’s not part of their current behavior.

In contrast, if you’re selling Allbirds shoes, it’s got new materials, it’s got a new line to it. People may think they’ll replace the old shoes with the new shoes, but that doesn’t change their behavior. Whereas a marketplace, you actually have to be envisioning a completely different equilibrium, a different behavioral environment. New information inputs, new decision-making processes, new ways of making money, new ways of helping people achieve their needs and wants. I mean, all these things are very human and those sorts of changes are filled with fear for many people. And so having new marketplace dynamics brings all that up and creates all that resistance when something changes.

And the advantages have to be great enough to overcome that resistance. Like I can swap in a new type of shoe because it’s clear to me that that shoe is better, but if I’m going to sell my car through a new platform, I have to believe that buyers will be convinced to join this platform. And imagine that the marketplace is creating enough value to bring those buyers on and they’re wondering the same thing. This is like the chicken and egg problem of supply and demand, but rephrased as a question of human behavior.

Listen to the podcast here>>>

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.